Epigraphic Reading

by James Stevens Curl (November 2022)

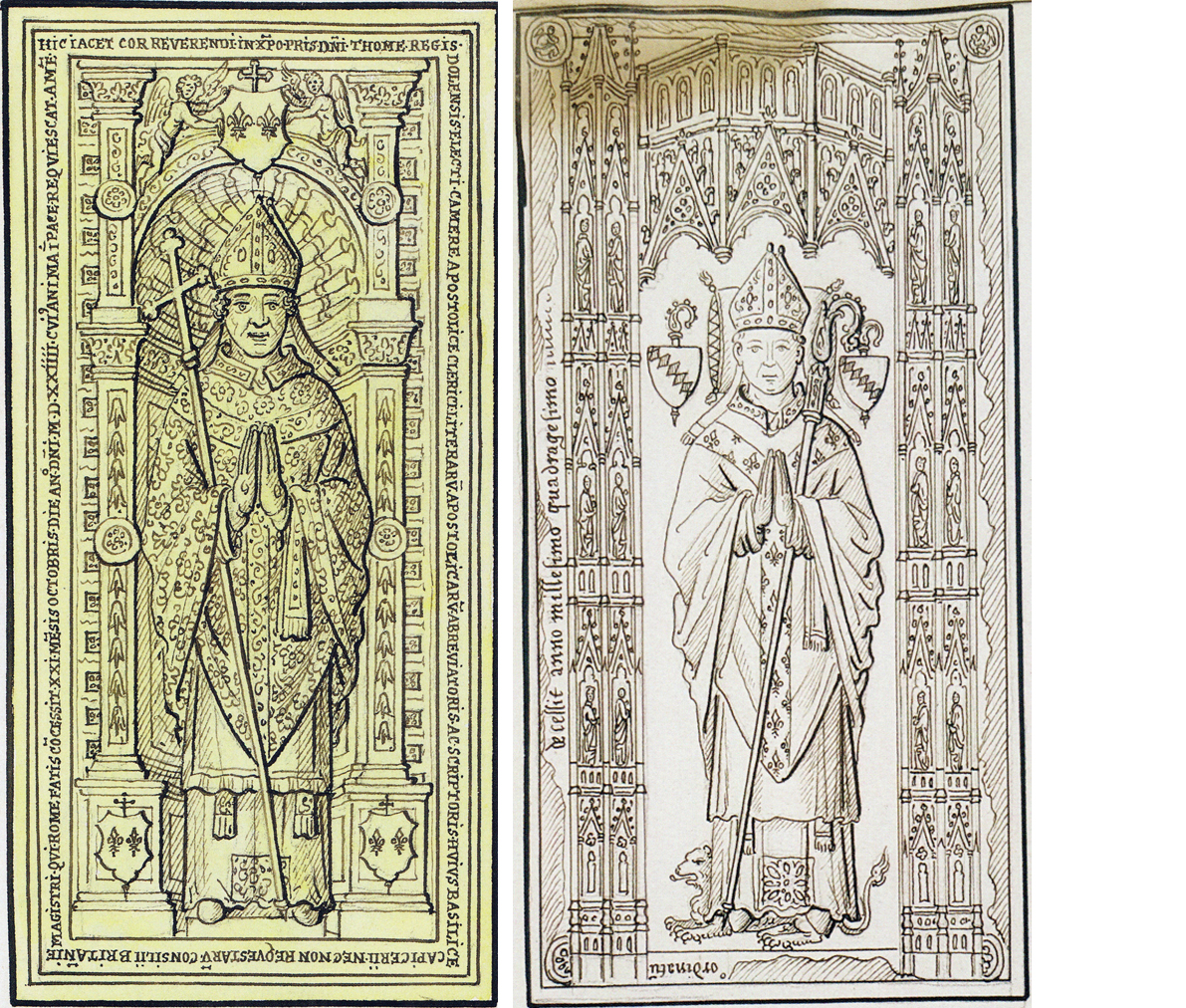

[Fig 1] The Incised Effigial Slabs of the Pays de la Loire: Bien graver

et souffissaument by Paul Cockerham (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2022)

This is an absolute corker of a book, crammed with well-researched information based on impeccable scholarship, comprehensively illustrated, with footnotes where they ought to be (rather than presented as those abominations known as ‘endnotes’ which are absolute pain to use, but are inflicted on readers by publishers keen to dumb down their productions, or make them appear less scholarly than they actually are in order to kow-tow to levellers and vulgar popularism), well designed, and finely printed (in England, not China, Laus Deo!). It deals with a fascinating yet curiously neglected topic, excepting the pioneering work of Frank Allen Greenhill (1896-1983), John Coales (1931-2007), and other intrepid investigators who have beavered away on the topic for a great many years.

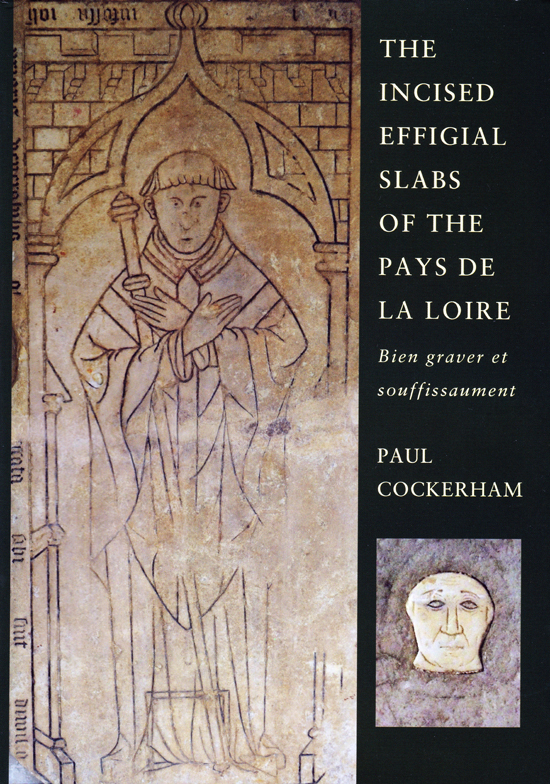

So what are ‘incised effigial slabs’? Haunters of old churches will be familiar with sculpted recumbent figures (effigies) on tomb-chests: these are often shown in armour, in elaborate contemporary dress, or in clerical garments, with canopies set beyond the heads, though horizontal, instead of vertical, as they would be if functioning as protections, either for practical or architectural/æsthetic reasons. Those figures provide invaluable historical evidence concerning fashions in clothing, heraldry, and much else, as well as being in themselves often very wonderful things. The incised effigial slab featured strictly two-dimensional portrayals of figures, cut into flat slabs of stone, and usually surrounded with an elaborate frame suggesting an architectural canopied niche. Incisions were often coloured with some sort of mastic to enhance legibility, and slabs were either set in the floor or on top of tomb-chests, although many may be found today in upright positions, set against walls, which prevents further wear and tear. So-called ‘brasses’ set into slabs were another variety, but this book deals mostly with stone slabs into which were cut the designs, although there are some ‘brasses’ included (e.g. that of Bishop Thomas Le Roy [d.1524] in the church of Our Lady in Nantes). The ‘brass’ used in mediæval funerary monuments was called latten, or latton, and was a pale-yellow alloy of copper and zinc (sometimes with small amounts of other metals such as tin and lead) resembling brass, sheets of which were cut, incised, coloured, and inlaid in stone slabs, though often serving as the whole covering of a stone.

As Cockerham points out, the ‘study of funerary monuments has advanced considerably and rapidly from an antiquarian focus to explore, for example, their socio-political significance’, but nevertheless, the ‘humble and literally downtrodden tombslab’ has been treated ‘as very much the poor relation’ compared with the wealth of all manner of artefacts that survive in ‘overwhelming abundance’ in the mediæval churches of France, despite the depredations of Revolutionary iconoclastic zealots and the fact, noted by Ausonius, that Death comes even to stone monuments and the names thereon. His wonderful book deals with exemplars found in the Pays de la Loire, just south of Brittany, which consists of the following historical Provinces: part of Brittany, with its old capital Nantes contained within the Loire-Atlantique Département; Anjou, largely contained within the Maine-et-Loire Département (the whole of the former Province of Anjou is contained inside Pays de la Loire); Maine, now divided between the Mayenne and Sarthe Départements (the whole of the former Province of Maine is now contained inside Pays de la Loire); a part of Poitou, contained within the Vendée Département; a part of Perche, in the north-east of the Sarthe Département; and a small part of Touraine in the south-east of the Maine-et-Loire Département.

Cockerham is a distinguished scholar of funerary monuments, and his erudite, well-illustrated papers in Church Monuments (the Journal of the Church Monuments Society, which he ably edited for a time) and other publications of substance have added lustre to that distinction. In particular, his detailed work on incised slabs is extremely impressive, and the discipline has served him well in this magnificent volume, which must have attracted hefty subventions to make it possible at such a modest retail price, despite the Subscriptions from individuals recorded in the book. And it is not only Cockerham’s archival archæology, keen eye, and intelligence that are impressive, but his diligence, patience, and persistence must be awe-inspiring, given the general inaccessibility of most French churches. Compared with England, where the church-crawler can usually gain entry to ecclesiastical fabric somehow or other, the ecclesiologist can have a rough time of it in La France, where, as Cockerham ruefully observes, churches are ‘all too frequently … quite impregnable’. I, too, found this often to be the case in my early forays in search of funerary monuments lurking in very rural France.

Of course, there are impressive collections of images of incised slabs in various places, and Cockerham draws heavily on the Gough Gaignières Drawings (MSS 18346-61) in the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, as well as on the capacious archives held in Angers (Bibliothèque Municipale and Maine-et-Loire Archives), Laval (Mayenne Archives), Le Mans (Médiathèque Louis Aragon and Sarthe Archives), Nantes (Archives Municipales and Loire-Atlantique Archives), Paris (Département des Manuscrits [Richelieu] and Département des Estampes et Photographies [Richelieu], Bibliothèque Nationale de France), and Tours (Indres-et-Loire Archives). I shudder to think how many hours, days, months, he must have laboured to obtain his material, as French obstructionist tactics are not confined to keeping churches firmly locked, but in my experience quite expert in obfuscation and even secreting material, finding all sorts of excuses to bar or delay access to it (not invariably, of course, as I have had wonderful co-operation and very helpful assistance in getting access to stuff in certain archives, not least in Mulhouse, many years ago, where the help I had was generous far beyond anything I have even known). But there are some very difficult archivists and librarians: I have come across rather too many of them, and still smart with a recollection of those frustrating times.

In this staggeringly detailed and beautiful tome, the author has done more than record the design and details of incised effigial slabs, but has analysed their meanings, and why patrons were motivated into commissioning and erecting such artefacts. The subtitle of his book—‘to engrave well and truly’—is apposite, given the high æsthetic qualities of what were often finely crafted objects. Most, but not all, of the slabs in the inventories Cockerham has compiled, are illustrated by photographs of the monuments themselves or by printed or drawn images of them. As this reviewer well knows, ‘taking good pictures of monuments in churches is not easy’, for ‘slabs and tombs are frequently treated as part of the church furniture and used as suitable surfaces on which to put notices, or to store boxes, vases, and all other types of impedimenta. French church interiors are often gloomy, and adequate pictorial contrast can be difficult to achieve’. Quite so, and indeed some of the less satisfactory images in the book demonstrate those difficulties rather too well. Nevertheless, there is much here on which to feast the eye, stimulate the mind, and trigger reflection on the only certainty in life, and how commemoration of the dead was once handled by the living (in a rather more impressive manner than is the case today).

This great book includes a large bibliography of primary and secondary sources that includes, I am glad to say, Montfaucon’s excellent Collection of Regal and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of France (1750), as well as the obvious works of Coales, Greenhill, several stalwarts of the Church Monuments Society, and many very distinguished European scholars. The annotations are extremely informative and full, as well as accessible, being footnotes, while the index (by Tyas himself) is exemplary. Altogether, this is a fine production, doubtless with limited appeal, but it is a worthy addition to the scholarship of an aspect of thanatopsis that has been in some respects undervalued, so it is a welcome corrective.

Fig. 1 Front of the wrapper of Cockerham’s book showing Jean, a late 15th– century Prior de la Haye-aux-Bonshommes, Avrillé, Maine-et-Loire, in Mass vestments, under an ogee cusped canopy, with (right) a detail showing the head of Jean Margerie, seigneur de la Drouardière et la Baroche-Gondouin (d.1513), parish church of La Baroche-Gondouin, Lassay-les-Châteaux, Mayenne.

Fig. 2 Incised slab commemorating William, Abbot (d.c.1247) of Asnières, Cizay-la-Madeleine, Maine-et-Loire, shown in Mass vestments. Note the colouring in the incised lines.

Fig. 3 Incised effigial slab of Girard de Bruyères (d.1418) and his two wives, Catherine, and Isabeau de Ramecourt (d.1427), formerly in the Collège des Bernardins, Paris (from Marie André Alfred Émile Raunié et al.: Épitaphier du Vieux Paris … ii [Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1893] 10).

Fig. 4 ‘Brass’ of Thomas le Roy (d.1524), Bishop of Nantes, originally intended for the newly constructed chantry-chapel of Saint-Thomas, church of Our Lady, Nantes, Loire-Atlantique. Note that the Gothic framework has been replaced with a Renaissance scallop-headed niche, shown partly in perspective.

Fig. 5 Lost slab formerly in the Chapel of the Virgin, Abbaye Saint-Serge-et-Saint-Bach, Angers, Maine-et-Loire, commemorating Abbot Guy de Lure (d.1426), shown in full Mass vestments, with dalmatic, the orphrey of his chasuble ornamented with fleurs-de-lys, wearing a mitre with lappets splayed laterally. The crook of his crosier is decorated with crockets and mini-niches. Note the full Gothic frame, figures in niches, and elaborate canopy.

Professor James Stevens Curl is the author of St Michael’s Kirkyard, Dumfries: A Presbyterian Valhalla (Holywood: The Nerfl Press 2021), which reveals many fine funerary monuments in glorious colour plates.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast