Sin and Art

by Noel Yaxley (December 2022)

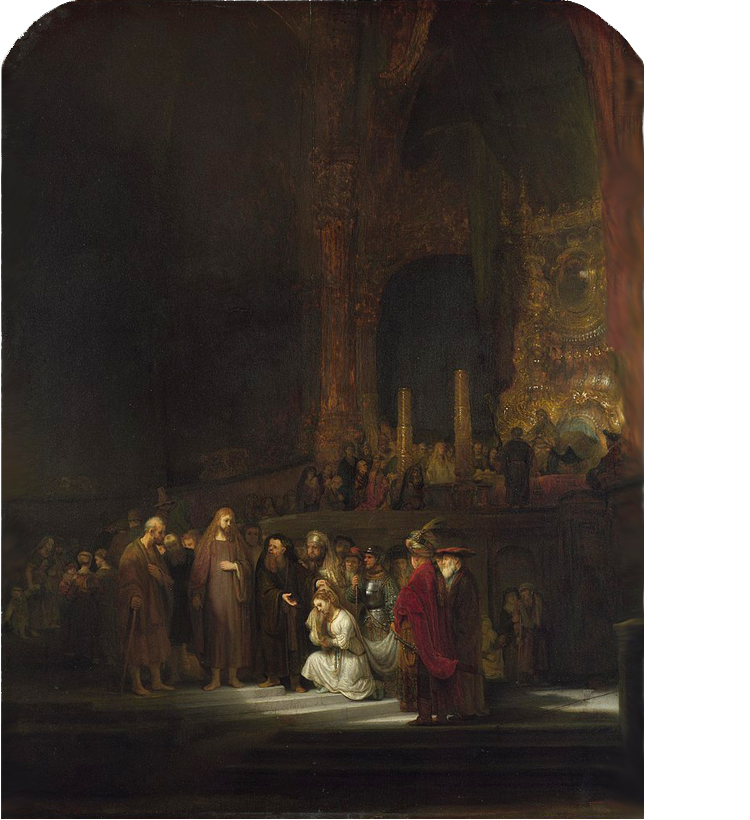

Christ Appearing to Saint Anthony Abbot, Annibale Carracci, 1598-1600

The depiction of sin has been fundamental to European culture for hundreds of years, especially—but not limited to—Christian art. Over the centuries, artists have found many powerful and compelling reasons to portray this all-encompassing condition. Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Adam and Eve takes us back to the origins of the story, known as original sin, while Hieronymus Bosch’s famous triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights, when taken in totality, depicts the fate of humanity consumed by pleasure and passion. Bosch’s masterpiece is arguably the western world’s most powerful representation of sin and its consequences.

Whether one defines sin as transgression against supernatural law, or an aspect of the human condition in which we regularly fall short of the good, we are all implicated in one way or another. In a theological context, sin is immoral, and in a secular world, it is something tangible, regarded as a serious offence or fault. It is this universal and relatable aspect of sin that is explored in a new exhibition at the York Art Gallery.

Morgan Feely, the curator of the exhibition, simply called Sin, explained the goal was to bring together works of art spanning centuries as a medium to invite visitors to reflect on their own ideas about sin and the state of society today. It poses a number of philosophical questions: Are humans capable of leading a life without sin? How do secular themes of sin differ from religious ones? Does art celebrate or condemn sin? And what does sin mean in an ever-changing world?

The exhibition aims to explore these questions through an examination of a number of major works from the western canon. In conjunction with the National Gallery, the exhibition features a collection of eight classic paintings interspersed with work produced by a local teen art school. Over two rooms, work by prominent artists such as Rembrandt and Tracey Emin sits alongside locally produced work by the next generation of young artists. Far from an incongruity, this juxtaposition perfectly encapsulates the pervasive influence the concept of sin still has upon us.

The first piece on display is The Penitent Magdalene by Anthony van Dyck. Mary Magdalene has always been a popular subject in western art and an important figure in the Christian story. Although Van Dyck’s oil painting is somewhat unimpressive technically, it perfectly captures the duality of sin and repentance. Mary Magdalene was an example of a repentant sinner who devoted herself to a life of contemplation in the wilderness. The depiction of her, alone in the woods, replete with a skull, holy scripture, and crimson coloured, upturned eyes, signifies both spirituality and divine retribution. The semi naked figure of her dominates the canvas, inviting the visitor to gaze upon her in a sinful manner.

Visitors are then presented with Annibale Carracci’s Christ Appearing to Saint Anthony Abbot. Aesthetically pleasing, it forms part of a series of works on copper that Carracci painted before arriving in Rome in 1594. It is unsure who this work was created for, but considering the use of copper was an expensive practice in 1598 when this was created, it has been suggested it was made for Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew of Pope Paul V. In Carracci’s painting, St.Abbot is shown prostrate under a tree being tormented by demonic creatures. As he looks to heaven for salvation, Christ has appeared on a cloud. The position of Saint Abbot appears to be heavily influenced by Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam. Carracci’s work might be small, but the moral warning it portrays is stark.

To illustrate how the concept of sin resonates throughout society, a number of contemporary pieces sit alongside these classic works. Standing in the centre of the first room is a sculpture by the British-based hyperrealist sculptor Ron Muek. At just over two feet tall, Youth is a powerful meditation on Christ’s crucifixion. Made using fibreglass, silicone, and resin, the attention to detail confers an almost lifelike presence. A dark-skinned boy with low-slung jeans is shown lifting a blood-stained shirt to reveal a stab wound in his side, an allusion to sin whilst incorporating modern-day concerns with gang violence and race.

Somewhat less impactful is Tracey Emin’s It was just a kiss. Always provocative, Emin’s work is deeply personal and regularly depicts sex, sexual abuse, and abortion. This piece—with the work’s title spelt out in handwritten neon lights—makes an oblique reference to the secular confessional world of the 21st century celebrity. The constant need to ‘confess’ one’s sins is a modern way to gain victim status.

As you move into the second room, viewers are greeted with art created by lesser-known artists, specifically 13-to 17 year-old students from a summer art course, focused on the theme of sin. Eschewing conventional artistic methodology, these young artists utilise numerous forms of media to represent a more humanistic portrayal of sin. A multi-channel film installation provides an immersive experience for the viewer, allowing them to think in both an imaginative and thoughtful way about how we can make sense of sin as we move forward in time.

The creativity of this immersive experience concludes with Zara Worth’s ‘Think of a Door (temptation/redemption)’. A Yorkshire based writer and artist, Worth’s piece, created specifically for the exhibition, is a six-foot neon-lit door frame. Described by the artist as a “mediation between tangible and intangible space,” it challenges the viewer to break with their preconceived notions of space. The notes accompanying the work urge the visitor to photograph it for social media, highlighting the ease with which images move. It is this fluid nature of representation and reality that would align Worth’s work with that of poststructuralism. The piece is ambiguous, a free-floating signifier with no objective referent. What it appears to represent is the ever-changing nature of sin.

The exhibition, which runs through January 22nd, 2023, highlights the importance of art in representing our conception of sin. With myriad forms of new media, it helps bring forth new ideas about a concept thousands of years old.

Noel Yaxley is a writer based in Norfolk, England. He spent four years reading politics at university before turning his attention to writing.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast