Why Do the Masses Crowd the Major (But Only the Major) Art Museums of the World?

by Guido Mina di Sospiro (December 2022)

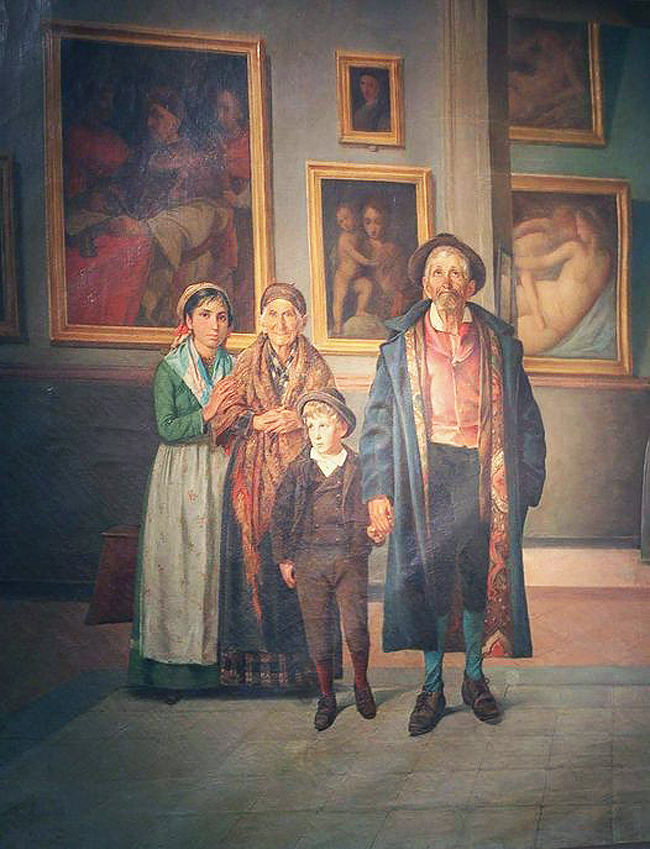

Scuole diverse (Different Schools), Antonio Augusto Moriani, 1890

Before returning to the US a few weeks ago, I visited the Museo di Capodimonte, in Naples, Italy, and took a picture of this painting—by Antonio Augusto Moriani, as it transpired, dated 1890. It represents four hillbillies inside a museum, completely out of place. The phrase La Vérité en peinture (The Truth in painting) came to mind, the title of a book by Jacques Derrida, which he himself took from Cézanne. I was also reminded of Roman Jakobson six functions of language, of which the one in the painting would be the sixth: the metalingual one, and that is, the use of language (Jakobson calls it “code”) to describe … itself. Indeed, here is a painter using a museum with many paintings in it to make a point.

The portrayed hillbillies still exist, though they are no longer peasants, but tourists, millions of them, wearing sneakers and shorts and wielding that quintessential implement of the 21st century: the smartphone. Opportunities for selfies abound and seem to be the main activity such visitors are preoccupied by. And, contemplation? Conferring with the muses? Not so much.

Again I must mention linguistics. In French, Italian and Spanish there are two very similar yet distinct words, respectively: langue and langage; lingua and linguaggio; lengua and lenguaje. Such two words correspond to the English word “language”; langue, lingua and lengua: chiefly used to refer to individual languages, such as French and English; and langage, linguaggio and lenguaje, which primarily refer to language as a general phenomenon, or to a language applied to another field, such as music, the fine arts, and many more. Therefore, it is easier for the French, Italian and Spaniard to understand that there is a language to be learned that deals with painting, another one with music, architecture, and so on.

Let us now imagine that my favorite Japanese author comes to town, to present his latest work. I don’t miss my chance and go listen to him as he is also, I have read, an eloquent and compelling speaker. At the end of the soirée, I am dumbfounded. He did speak, and at length, but in Japanese for the whole time, and with no interpreter present. All his words, no matter how interesting and vibrant, were lost on me.

That is what happens to the millions of casual (major) museum visitors who patiently wait in line for hours for their turn at the Louvre or at the Uffizi: everything they then see is lost on them because they don’t know the language of painting. And in fact, just by observing them, one can discern everything but appreciation, let alone awe or emotion. So, why do they bother? Why do they crowd all major museums, but only the major ones? “Minor” museums, in fact, are consistently deserted just about everywhere (and a delight to visit); if they were really keen on the arts, they would visit them all.

It is as if the unknowing masses were mandated to do something they could not possibly understand. Remember the analogy with the Japanese author.

In one of my very rare posts on Facebook (since deleted), commenting on Antonio Augusto Moriani’s painting I wrote:

“‘We don’t speak the language!’ When visiting museums nowadays, one comes across the same category: tourists wearing shorts and taking selfies are the contemporary hillbillies. The question is: why do they go to museums at all?”

Wouldn’t you know it? I unleashed the paladins of flatulent egalitarianism (rank nonsense in the instance of knowledge) and the enforcers of inclusiveness. The smartphone-wielding casual museum-visitors have all the rights to be there, with their attendant short attention span pathology and garrulous triviality.

I do not question their right to be there, unless their aim is to throw tomato sauce on a painting or two, but wonder at how much fun it can be to parade in front of dozens and dozens of paintings without speaking their language.

I should further clarify this concept, since, as noted, the English language does not have the right word for it: if I say, “In the Emperor Concerto Beethoven resorts to enharmonic modulations” those two last words are completely lost on the layman. And even if he were to read what “modulation” means in musicological terminology, he still could not understand the concept, as it would refer him to “tonality,” with its complex system of chord progressions. Only somebody who plays an instrument capable of producing chords and is familiar with tonality can understand the concept of modulation, which is quite central in the development of western music.

What rubbed the paladins of flatulent egalitarianism and the enforcers of inclusiveness the wrong way, though they would not know it, is the concept of initiation, which is a fundamental concept in traditionalism, but we live in very anti-traditional times. The so-called expert is in fact an initiate. By din of studying and learning about different periods and contexts in the history of art, the Biblical and Greco-Roman mythology that so often inspired the old masters, different schools, different individual painters and differing techniques, and of course visiting as many museums and galleries as possible, the art enthusiast gradually acquires the language of art. The more she deepens her studies, the more fluent she becomes; eventually, she will be an initiate. But that can only happen over a long period of time.

I have visited the Uffizi in each decade of my life, starting in my teens. Each time it has been a richer experience, though the paintings have remained largely the same. That is because each time I went back, I was a little more fluent in that language, which is not to say I have acquired perfect fluency in it yet.

A book I recently read comes to mind, L’occhio dell’artista. Una lettura oftalmologica della storia dell’arte (The Eye of the Artist. An Ophtalmofgical Reading of the History of Art). The author, Cesare Fiore, an ophthalmologist, goes through the history of western art by examining and reconstructing the eyes and vision defects of some of its great masters. It is a book that took him decades to research and write, and could not be more intriguing. In it, two languages converge: that of ophthalmology and that of art. It would have been wonderful to go to a museum in the company of Dr. Fiore, but sadly he recently passed away.

Since we live in the tutorial age, one in which anything can be found on YouTube, including the most refined lessons in music, art, architecture and just about every other field of human endeavor, countless languages can be learned by anyone, from the comfort of their home, and for free. All such languages have never been so at everybody’s reach. And yet, what we get are the smartphone-wielding masses preoccupied with their next Instagram post—of themselves, rarely of the masterpieces in front of which they stand.

In my YouTube wanderings I have come across an admirable classical guitarist from Sweden—one Lucas Bar—who has had the following to say:

“I had a bit of talent and artistic inclinations as a kid, but 90% of mastering something is becoming obsessed with the joy of learning, realizing you will never master it anyway. There is no reaching the end point. So just enjoy the journey.” Lin Yutang could not have put it better.

Table of Contents

Guido Mina di Sospiro was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an ancient Italian family. He was raised in Milan, Italy and was educated at the University of Pavia as well as the USC School of Cinema-Television, now known as USC School of Cinematic Arts. He has been living in the United States since the 1980s, currently near Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books including, The Story of Yew, The Forbidden Book, The Metaphysics of Ping Pong, and Forbidden Fruits.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast