92 And Not Dead Yet: Culture By The Yard

You may have been hurt more than I have by the lockdowns. You may have lost your job or your spouse. The business you built by sacrifice and risk may be in ruins. You may even have put a bullet in your brain—inexpertly because you’d never done it before—and are reading this article in an asylum. But, I assure you, I’ve suffered too.

My problem: library books.

For weeks the local libraries were closed, then operated on a tightly restricted schedule. On my list of local services that I can do without, the library comes near the end. If the power goes out there’s the camping stove, if the trash truck doesn’t arrive you can throw your biodegradables over the neighbor’s fence, if the water is switched off you can squeeze moisture from plants. But without the books you want, who is there to tell you what to think?

I don’t leave home, even on the simplest errand, without the security of something to read. The line at the checkout might suddenly grind to a halt if a dispute erupts about food stamps. Maybe a magazine will be enough in such cases but for pharmacies, that have to determine what is or not covered by insurance, only a volume of short stories is safe, most post offices need a good-sized novel and doctors’ offices the Complete Works of Shakespeare.

I had a small cache of library books at home when the pandemic hit and plenty of books of my own, though I quickly found out there weren’t nearly enough that were sufficiently entertaining. Like the books that invariably form the backdrop to television interviews at the homes of our intelligentsia, many of them were there because I thought no civilized home should be without them, readable or not.

In those early days, however, I was saved by a trove—an amassment—of art books, that I’d bought and scarcely looked at. They gave me many hours of pleasure. I acquired them by pure accident months before when, wandering into the library one day I found a sale of these opulent books had been going on all week and now had only one more day to run.

Beautiful books, full of faithful reproductions or photographs, that had been offered for $20 were now being sold for $10 or less. Or rather not being sold. Even at that price the thrifty bourgeoisie of our neighborhood (of whom I am a fully representative member) couldn’t be persuaded to open their purses. I rummaged through the glistening pile for a while, like a miser with a cascade of gold coins, but nothing affordable showed up and I turned to go without a single Rembrandt under my arm. As I did so, however, the head of the Friends of the Library stopped me and whispered, “Tomorrow is our last day. We’ll be selling everything for $2.”

I was there at 8.55 am, expecting a crowd of professional booksellers with sharp elbows, but only an elderly lady was waiting who I felt I could push over if The Atlas of World History became a bone of contention. But, no, she was interested only in fiction which was being sold for a dollar a bag, sight unseen. I found myself browsing alone among books such as the one with every New Yorker cartoon in it, Harold Evans’ elephantine collection of photographs of the key events of the 20th century and collections of art from classical to impressionist. “This will never happen again,” I told myself and bought accordingly.

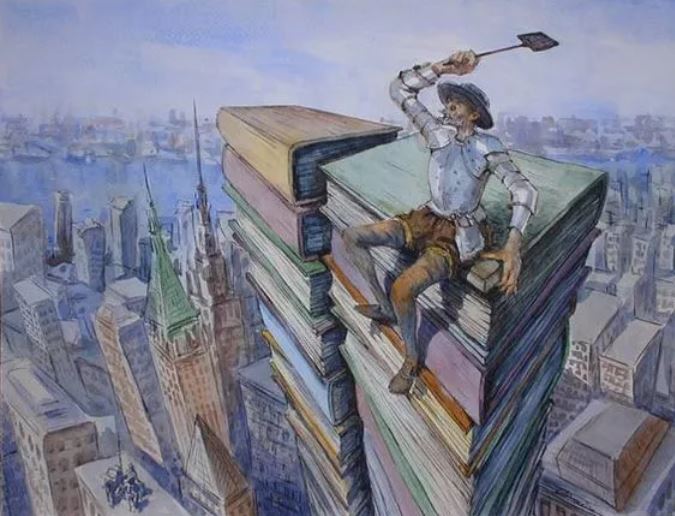

Where culture is concerned, when the price is right, for me the sky’s the limit.

Photo Credit: Eleanor Green