A Brief Reflection on Wittgenstein

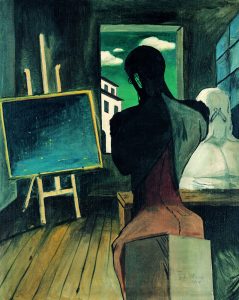

The Poet and the Philosopher, Giorgio de Chirico, 1915

I thought I was done with Ludwig Wittgenstein after my essay “demoting” him in my book Neither Trumpets Nor Violins (the volume itself, not the essay, co-authored with Theodore Dalrymple and Kenneth Francis), but the Philosophy community’s celebration of sophisticated incoherence continues. Instead of continues one might say spreads: I’m quite sure The New Yorker, whatever its many virtues, has no particular reputation for metaphysical speculation. I would like to understand what it is about this intellectual poseur that appeals to so many intelligent people who should know better. Nikhil Krishnan’s review-essay (in the May 16 New Yorker) occasioned by the newest edition from Private Notebooks: 1914-1916 is no help, although that is not Krishnan’s fault. The essay is titled “You’re Talking Nonsense”—not Krishnan’s judgment of Wittgenstein, but a characterization of Wittgenstein’s judgment of philosophers from the ancients to the moderns. It does capture my own judgment of Saint Ludwig, however.

I am not going to reread him again, looking for the possibility that I am wrong. I have suffered enough in life already. I have said this before, but there is no other philosopher I would more rather avoid unless it is Martin Heidegger. I have also said this: your average philosophy major at a respectable college has read more than Wittgenstein ever did as he dismissed with such hardly veiled contempt his philosophical betters. (As Iris Murdoch once said, “Wittgenstein had in fact not troubled to read some of his best-known predecessors.”) And I will say this for the last time: Wittgenstein’s philosophy amounts to the avoidance of philosophizing. Having made that promise I know immediately I will have to break the promise later on.

But what ostensibly is “Wittgensteinism”? That’s hard to say, for multiple reasons. There are Wittgenstein I and Wittgenstein II, the first found in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, the second a supposedly radical reformulation of his thought, Philosophical Investigations. There is, however, no consensus as to what the gnomic utterances of the Tractatus or the Investigations really mean as collective statements even if an individual gnomic utterance may be an internally coherent statement. The most radical evidence of this is the fact that when Bertrand Russell, whose earned stature as a thinker is undeniable, wrote an introduction to the English version of the Tractatus, Wittgenstein was furious, claiming that Russell understood the work not at all. Bertrand Russell!? If Russell did not, I daresay it was because the work itself was not understandable. A semi-comical event occurs to me at this moment:

David Edmonds’ and John Eidinow’s book Wittgenstein’s Poker seems, I think, subject of an ironic revelation. At an intellectual meeting at Cambridge in 1946 Wittgenstein and Sir Karl Popper of the London School of Economics got immediately into a heated argument about whether there were real philosophical problems or only linguistic ones, Ludwig taking the latter position, and making his points with emphatic gestures with a fireside poker, and demanding that Sir Karl provide a clear example of a moral rule. When Popper answered, “Not to threaten visiting lecturers with pokers,” which should have, it seems to me, made all break into laughter. Instead, Wittgenstein threw the poker aside and stormed out of the meeting of which he was the host as chair. This strikes me as the action of a frustrated speechless bully. So: for all that he talked and talked and talked, it seems possible to me that Ludwig Wittgenstein was ultimately simply inarticulate; no wonder he was incomprehensible.

But if there are individual statements that are internally coherent perhaps the two most famous are the following. (1) If we will recognize that when we use the word “world” we only rarely mean the geologic physical creation, but rather all-that-is available to our experience as we live, as in “It’s a wonderful world,” or “It’s a lousy world,” or even “The world can go to hell as far as I’m concerned,” or so forth; then there is the gnomic utterance “The world is all that is the case.” Who’s going to disagree? I recall being charmed when I read that. But how is that different from “the world is all that truly is” except that “is the case” sounds profounder than “truly is”? How about “the world is what it is.” Well, the latter has maybe inescapably a tone of disappointment and dismissal, a sense of that’s-all-there-is-to-itness. So while I still like “the world is all that is the case” what does this apparently coherent statement really mean?

About (2) I really get exercised: “Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darueber muss man schweigen.” Two popular English translations: “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence” or “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Understand first what Wittgenstein is not saying. Were one to say, for instance, “Since I cannot speak about my father’s Mafia connections I must remain silent,” who but a prosecuting attorney would object to one’s silence? No, nothing of that nature is meant. Rather, since metaphysical statements are necessarily nonsense (so says Saint Ludwig), “The correct method in philosophy would really be the following: to say nothing except what can be said, i.e., propositions of natural science.” In other words, since there are philosophical problems which seem or are unsayable, ineffable, don’t try to talk about them. That’s why I characterize Wittgensteinism as the avoidance of philosophizing itself. In other words (if one is allowed to speak in words!), don’t do what was done by Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Descartes, Hume, Kant, et al, et al, et al, on up to the present! Wittgenstein seems ignorant of the physical scientist’s need to challenge the ineffable as well. It was Niels Bohr who said that science has the responsibility to try to talk of its efforts in the language of common discourse, not relying on mathematics alone. Which Einstein surely knew. Wiuttgenstein was evidently an adequate soldier in World War One for Austria. But philosophically he had no courage.

Immanuel Kant, for but one example, had courage. Knowing the distinction between the phenomenal (that which appears to the human senses and intellect) and the noumenal (that which exists but is beyond sensual etc. availability), Kant in his metaphysics tried heroically to evoke the noumena although it is beyond coherent language, and the shape—so to speak—of the human mind is such that the noumena cannot conform to it and remains mostly unrevealed. Without Kant Western philosophy would be a lesser affair, but it must have been a bore to Wittgenstein (as it was mostly ignored by British philosophers of that time). Without Kant there would be no Schopenhauer. Without Schopenhauer, Nietzsche is hard to imagine. Without Wittgenstein, Western thought would be richer. What really is one to make of a “philosopher” who writes near the end of the Tractatus of his propositions, “he who understands me finally recognizes them as senseless”? Why should one bother? But bother many do.

One who does is the prominent English philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe. Which I find disappointing. Krishnan’s subtitle is How Queer Was Ludwig Wittgenstein?—referring both to his odd philosophy and his more or less confessed homosexuality. Anscombe is right to object to any emphasis on the latter issue, so one can hope that is what she is referring to when she writes, “I feel deeply suspicious of anyone’s claim to have understood Wittgenstein. That is perhaps because … I am very sure that I did not understand him.” But it’s a real stretch to assume she is talking about the man’s sexual inclinations; she is talking about his thought … so what an extraordinary confession.

In this context it is interesting to contemplate the reaction to Wittgenstein of the wonderful novelist-philosopher Iris Murdoch, who’s magnificent Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals is real philosophy. Krishnan notes that Murdoch met Wittgenstein twice, finding him interesting as a person, but “failed to get much philosophy out of him.” Exactly!

So what for god’s sake is the appeal? I get no pleasure from the conclusions I come to about the academic discipline I practiced for decades, for I still think Philosophy the monarch of the arts and sciences (although the old term was queen)—which does not mean every academic practitioner is noble or aristocratic of course. And when we talk about the Wittgenstein craze we are talking about academics, not incidental philosophers.

John Crowe Ransom, commenting on the relative obscurity of literary criticism in his day, proposed that the critic wanted to show his depth by seeming as difficult as the physical scientist. It is surely significant that Wittgenstein thinks that whereof one can speak are “the propositions of natural science,” even if, one has to assume, such a proposition is so deep as to be obscure to the reader or hearer. Am I suggesting he was practicing bad faith? I suppose I am at least “suggesting” it. But there is a class of academic philo prof about whom I am more than merely suggesting …

He or she (usually he) doesn’t much care for the likes of Descartes or Hume or William James or John Dewey, given their depth and clarity at the same time. He doesn’t necessarily prefer Kant, who can make one feel stupid and look stupid. But a thinker on the order of Wittgenstein (or Heidegger for that matter) possesses the twin obscurity and incoherence that make his stuff look as deep as sub-atomic physics, requiring explication as deep as what the quantum physicist provides. This class of prof is cousin to the English prof who avoids, say, Robert Frost in his Intro to Lit, something like “The Road Not Taken” not needing much explication de texte, unless the explication is to show the students that Frost cannot really mean what he apparently means; he will prefer, say, T.S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets,” which can be opened up only by a Lit prof who is just as smart as the physicist.

There’s another way of looking at this issue, which requires again an analogy between the English and the Philosophy departments. There is a certain class of English professor who is delighted to inform his students that most of the rules of English grammar that they learned in school back home have no bearing now. “Prescriptive” grammar is a dead issue, because grammar evolves over the years driven by the “usage” of actual speakers of the language. The second clause in the previous sentence is of course true; but the first clause is true only because prescription has been murdered. Professor Knowitall will tell his flock that the old rule that you cannot begin a sentence with a preposition or an infinitive or a whatnot no longer obtains … although such never was prescribed in the first place. He will not tell his students that the basic structure of the English sentence requires a subject and a verb and often a direct or indirect object … because that is indeed what is prescribed by the universal “Cartesian” grammar that underlies language itself. He feels that emphasizing Usage at the cost of Prescription makes him seem a brave champion of freedom and linguistic democracy. Prescriptive Grammar he thinks means someone, with no right to do so, is telling somebody else how something should be said or written. Of course that “someone” is intelligent tradition, which knows that I, you, we, and they write, while he, she, or it writes. But Professor Knowitall would allow that dialects that allow, for instance, “he write” and “she write” are just as good as the prescribed subject-verb agreement even though it makes the speaker sound illiterate. However, of course, no surprise, the good professor him—or herself speaks and writes according to the prescriptive grammar bravely dismissed.

Philosophy profs are generally smarter than English profs (I have been both, so no boasting here), so they will avoid sounding so stupid. But there is a similar dismissal of trusted tradition which embraced questions of the nature of being, of the soul, the limits of knowledge, choice, ethics, God or his absence, the meaning of beauty, and wonderfully so on, and, as I have put it elsewhere, “the necessity of talking about these matters.” To approve the dismissal of that tradition for the sake of not speaking of the ineffable can make one seem oh-so-brave, as if one were saying, “I don’t really like this myself, but some of us have to be strong and resolute enough to do what, maybe even tragically, has to be done for the sake of truth.” One can become inebriated on such pseudo-sacrificial self-congratulation.

If this sounds cynical of me, so be it. My cynicism is inspired by that of another kind possessed by a garden-variety philo prof. But my explanation of Saint Ludwig’s reputation does not explain why a quality figure such as Elizabeth Anscombe could hear a profundity from him that a greater-quality figure—I think—could rarely hear: Iris Murdoch. In any case, I know of no other well-known to famous Western philosopher (aside from, for the moment, Martin Heidegger) about whom the most significant question about him or her has not to do with the substance of the work, but, rather, with the justice of his or her reputation.

Ludwig Wittgenstein in effect said to Philosophy, “Commit suicide!” How dare the son of a bitch.

Samuel Hux is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at York College of the City University of New York. He has published in Dissent, The New Republic, Saturday Review, Moment, Antioch Review, Commonweal, New Oxford Review, Midstream, Commentary, Modern Age, Worldview, The New Criterion and many others. His new book is Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Kenneth Francis)

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast