A New Old Game

by Robert Gear (April 2022)

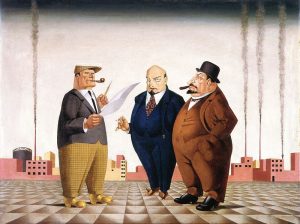

Of Things to Come, Georg Scholz, 1922

At the risk of wading in where angels and many others have already trodden, here are a few thoughts relevant to the current situation in Eastern Europe.

We can glean some insight from Ludwig von Mises’s words in his 1927 work, Liberalism. He writes:

Ever since Russia was first in a position to exercise an influence on European politics, it has continually behaved like a robber who lies in wait for the moment when he can pounce upon his victim and plunder him of his possessions. At no time did the Russian Czars acknowledge any other limits to the expansion of their empire than those dictated by the force of circumstances. The position of the Bolsheviks in regard to the problem of territorial expansion of their dominions is not a whit different.

Could it be that something in the character of the inhabitants of this giant country leads them (or their dictators) to adopt an aggressive posture, ‘to push where there’s mush,’ as Lenin famously encouraged his comrades. I leave aside the question of whether or not other great powers have been ‘a whit different’ or indeed of how much responsibility they must share for this recent installment of mayhem.

The basic motives behind war in general according to Thucydides in The History of the Peloponnesian War are three: Honor, Fear and Interest (Security, Honour and Self-Interest, in Rex Warner’s translation). Donald Kagan, in his On the Origins of War sees these as decisive elements throughout recorded history. Perhaps all three help manifest themselves in character; as may topography, geography, location, climate, historical trauma, the predilections of particular despots, and for all we know the flapping of a butterfly’s wings, and so on.

But what about the Russians? The character and proclivities of a well-known Russian despot is well attested in John Evelyn’s diary entry for February 6th, 1698. He records that:

The Czar Emp: of Moscovy [Peter the Great], having a mind to see the Building of Ships, hired my house at Sayes Court, & made it his Court & palace, lying & remaining in it …

Not altogether surprisingly, Peter, who had something of a reputation for riotous living, was far from a model guest. He proceeded to comprehensively trash Evelyn’s house—knocking a hole in the wall to allow easier access to the shipyard at Deptford. He and his entourage apparently broke over three hundred windows, twenty pictures and fifty chairs. The paintwork of Sayes Court was ruined, and the curtains, bedding and floors were smeared with ink and grease. Worst of all, the young Tsar destroyed the diarist’s pride and joy, the “impregnable” hedge in his garden, “four hundred foot in length, nine foot high, and five in diameter.” It was claimed that Peter enjoyed being pushed through the magnificent hedge in a wheelbarrow. So much for the young Czar’s merrymaking, a small-scale ‘scorched-earth policy’ practiced a few years before he really got into the swing of it in his war with Charles XII of Sweden.

Czar Peter’s performance could well be used as a pilot episode for a show to be called ‘Houseguest from Hell.’ But then, such a potential ratings triumph may already exist in the world of trivia broadcasting. Perhaps too, ‘we warranted no better, I don’t know,’ as Larkin might have put it. Indeed there are compensations for not owning a ‘goggle box,’ or as they now should be renamed ‘goggle walls.’ These permit an ‘immersive’ experience enabling one to watch the unfolding tragedies and comedies of the world from the comforts of ones own rooms (in my limited experience there being a giant flat telescreen contrivance in more than one room of the average suburban house).

So character must count for something. Peter’s foibles appear rather like the antics of British ‘yoof’ during their Mediterranean sojourns. The difference being, though, that Peter was considered ‘educated’; the yoof, not so much. Whatever the case, character sometimes truly is destiny, as Heraclitus noted about 3000 years ago.

What is the character of Russian elites and people? Theodore Dalrymple in his essay, How to Read a Society, discusses the brief visit to Russia in the 1830s of the French essayist, the Marquis de Custine. This thoughtful aristocrat enlightens the reader about the Russian character of that time and place. The maintenance of Russian despotism depended on a ‘universal vocation for untruth’ without which the population would be uncontrollable. And as is more widely known, Tocqueville, Custine’s contemporary and kindred national studied the effects of political liberty on the human character in the early United States, and broadly speaking found that such liberty produced honesty, plain dealing and enterprise: virtue without external coercion. These are qualities which are decidedly the opposite of those Custine observed in St Petersburg and environs.

Can this argument still be made? No doubt, many factors play into any Russian leader’s decision to ‘pounce,’ and there is plenty of blame to go around in the current imbroglio, including much meddling, whether incoherent or planned by Nato countries in a bid to influence the alliances of the large buffer state. However, the decision by Putin to invade, with all the consequent misery this has already entailed does seem to conform to Mises’s accusation and de Custine’s observations.

Of course, much of what Custine observed may now have significance beyond that vast country: the effect of despotism upon ‘human psyche and character.’ Judging by burgeoning displays of ‘cancellation’ and bullying in our own ‘law and liberal’ societies no nation is immune.

But the resolve to engage in aggressive actions seems to be strengthened by the perceived failure of potential adversaries to apply strength or deterrence.

Here are three very notable and, historically speaking, recent examples of the Russian empire ‘pouncing’ at moments when the leadership of the United States has been recognized as feeble.

Take, for example, the 1962 Kennedy/Khrushchev meeting in Vienna. The Soviet leader came away with a view of Kennedy that is less than flattering. In his opinion, Kennedy was overly cautious, and unlikely to stand up to bullying. Kennedy, himself, admitted privately to Richard Nixon that his own failure in the Bay of Pigs fiasco might have led the Chairman to the belief that “he could keep pushing us all over the world.”

Clearly, the Russians thought they were dealing with an indecisive weakling. As it turned out, of course, during the missile crisis of 1962, Kennedy showed more firmness than his Soviet counterpart had anticipated. But then, the crisis may well not have developed had the US leader shown a more forthright understanding of Communist ‘managerial style.’

Next, we had the example of President James Earl Carter Jr, whose failure to understand international affairs was glaring from the moment he stepped onto the stage of US politics. He was truly a paper tiger, or gave that impression to interested observers. Brezhnev (or Brezhnev’s handlers, for by this time the Marshal had suffered a stroke and was in poor health, not just physically. Yes, he has a modern counterpart nearer to home.) took one look at Jimmy and started preparations to ‘pounce’ on Afghanistan. True, in the longer term this turned out to be a pounce too far for the communist regime; some would argue that this was a decisive element in the eventual fall of the evil empire; History is cunning.

As a personal aside, I traveled in Afghanistan in 1974 and met several Russian ‘engineers.’ I even decisively lost a chess game to one who was enjoying the comforts of the flea-bag hotel in which I lodged in Kabul (a very small game being played in the shadow of The Great Game). And what had these engineers been required to do in Afghanistan? They were there to develop a road system on which to maneuver their military vehicles.

By the way, the reason why there were so many chess sets on the loose in Kabul was a mystery to me until I realized that Soviet citizens could barter them with Afghani tribal members in exchange for western cigarettes and other, for them at least, communistically unobtainable luxuries. What the locals thought of these strange checker-patterned boards replete with curiously plasticated and often unislamic figurines would have confounded Sherlock Holmes.

And now we have a sitting President who is perceived, by friend and foe alike, as the least competent and most feckless in modern US history; sometimes perceptions and reality do coincide. And so the current ruling Russian autocrat has pounced again.

Von Mises had an astute understanding of the perpetual aggressive posture of Russian elites. Perhaps, those who want peace should understand the same. The Great Game is an old game.

Robert Gear is a Contributing Editor to New English Review who now lives in the American Southwest. He is a retired English teacher and has co-authored with his wife several texts in the field of ESL.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast