A Writer’s Syndrome

by Peter Glassman (May 2021)

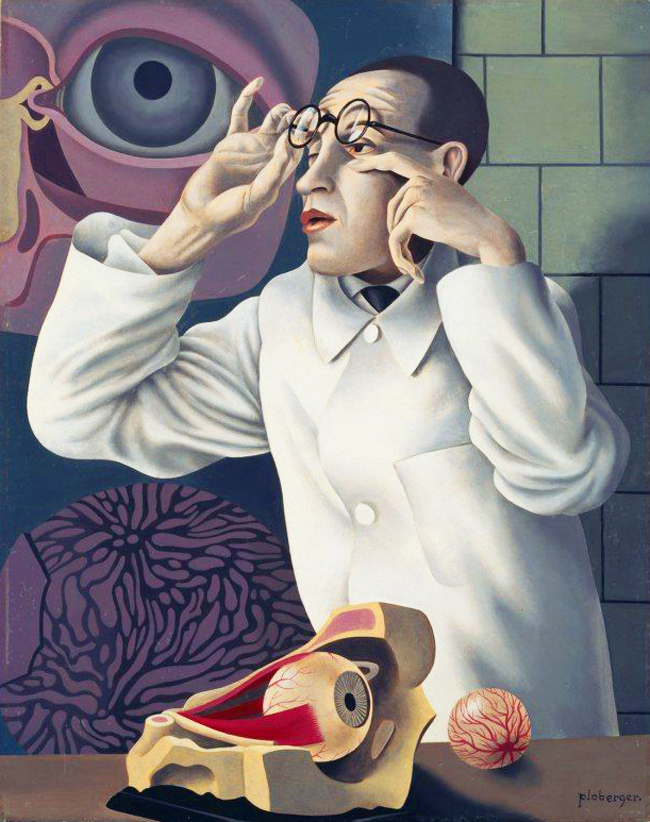

Self-Portrait with Ophthalmological Models, Herbert Ploberger, 1928-30

What does a writer do when connecting thoughts stand still—when there’s no hook to the next chapter? Writer’s block is a syndrome of a need for a person, place, or thing (or all three) to erase a void in a story’s plot. It’s a mental phenomenon wherein a character or situation cannot proceed further. The author must see if a new character, action, or place can go to the next milestone. It may be the time to invent a disposable person, place, or thing to act as a bridge. Such realization has put the phenomenon of writer’s block behind me.

In my crime thriller, The Eyeman, I needed a murdered victim to be discovered by the FBI. None of the characters so far in the novel could do this. I had to invent a person to discover the body under credible circumstance and not be a distraction to the story line.

For five-hundred words, I had an illegal solid landfill purveyor discover the body. While stealing landfill from a building site he uncovered the murder victim. He called the police who called the FBI and, because he didn’t want to be caught with his illegal dirt, he left the scene. After the phone call he disappeared from the cast of characters, from the book, and from the planet. His only existence was to enable the FBI to move ahead in their pursuit of a serial killer.

Part of my ability to overcome this writer’s malady is from my learning about syndromes in my career as a physician. A syndrome is a collection of signs and symptoms that by themselves do not define a complete disease entity. Like a novel it has a beginning, body of milestones, and an ending. A syndrome also has a history or storyline, which, like fiction, has a plot to go from start to finish.

Two memorable syndromes are still helpful to me today from my past medical practice. Tsutsugamushi disease is one and the second is called Phiniminiiasis. Both taught me thoroughness and paying attention to detail.

***

Tsutsugamushi Syndrome is one my kids used when they were teenagers. My middle child Michael, with his two siblings, David and Tracy (oldest and youngest respectively), stole one of my prescription pads. Their goal was to use it for personal gain—not for prescribing drugs, but for use to skip high school classes. Michael, who would in later life become a successful medical researcher, opened my Harrison’s Textbook of Internal Medicine.

His eyes gleamed with his words, “Hey, let’s look in the table of contents for a good disease to cut class.” Michael had their attention.

Tracy signaled with a raised hand, “Tsootoo… something. It sounds like a good one.” She wrote the name down inside the sentence they had made up on a prescription blank and read it aloud, “ David, Tracy, and Michael Glassman have come down with Tsutsumagushi syndrome and will be absent from school the next three days.”

Michael agreed and added some of the syndrome’s components, “Their spotty rash, fever, swollen glands, and headache, require home care and medical treatment.” He gave the prescription note to a classmate who lived next door. “Give this to the front office desk on your way in tomorrow. We’ll return the favor when you want to cut class. We have a whole prescription pad.”

***

The school nurse, Miss Nancy Scratchitt, received the note. Scratchitt reflexly entered the kids absence and the reason. She also sent out an alarm to me.

I was in the recovery room with a patient emerging from anesthesia when the OR nurse told me the high school nurse was calling. Miss Scratchitt was a serious healthcare worker who the students were always trying to scam, but rarely succeeded. She read the words from the forged prescription sheet.

I had to laugh, “Thanks for calling, Nancy. Tsutsumagushi Disease, they must not have read the details of the Tsutsugamushi syndrome.”

Scratchitt didn’t laugh, “This is no joke, Dr. Glassman. I’m shocked that your children have done this.”

“What signaled you to the ruse, Nancy?”

“Well, I remembered the syndrome only occurred in Australia or in the tropics. I looked it up in my medical dictionary and confirmed it.”

“Good call, Nancy. Tsutsumagushi actually occurs mainly in Madagascar. It’s a rickettsial disease like Rocky Mountain Spotted fever and its transmitted only by the bite of a rat mite.”

“What should I do, Doctor? I mean they are your kids and all.”

“I’ll take care of it. My wife’s at work. I’ll call Officer Ferguson at the Police Department, he owes me a favor. I’ll send him to my house. Coming to school in a police car should scare them.”

***

Phiniminiiasis is another syndrome I’ll never forget. It’s from my post-medical school training. New healthcare workers are afraid to question their superiors. Many life-threatening mistakes are avoided by making an adjustment to that attitude. A factitious syndrome is one way to do this and I was to be the unknowing brunt of one of them.

I was in my first week of a gastrointestinal (GI) medicine rotation. Dr. Luther Liscomb, head of the department, supported the hazing of the new doctors. It was a means for them to self-discipline and go to the medical literature to find information on a medical entity they didn’t know.

“Doctors should not fake knowledge. A good doctor is one who admits he doesn’t know everything,” was Liscomb’s frequently spoken adage.

A Senior GI Resident was presenting a young female patient at bedside during morning rounds. She had complained of cramping, bloating, loose bowels, and foul fetid flatulence. Liscomb singled me out and asked me what diagnoses might be considered here.

I swallowed and recited a list of the most common serious and less serious bowel maladies with her presenting complaints.

Liscomb seemed pleased and told us that a colonoscopy later this morning might confirm her working diagnosis of Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

Liscomb faced me as we left the patient and said, “I didn’t want to ask you this in front of the patient, Dr. Glassman, but your differential diagnosis did not include the Phiniminiiasis Syndrome.”

“Phini…mini…iasis…?” I looked at the other residents for help. They kept silent.

I was advised to read up on it and present the specifics to the group before tomorrow morning’s rounds.

***

I spent most of the night in the medical library and on the internet. I couldn’t find any option for an illness or syndrome complex under the Phiniminiiasis title. I was dreading morning rounds. Before we approached the patients I was confronted about the elusive GI syndrome.

I gulped my coffee and told Liscomb, “I checked every GI journal and every textbook in our library. I even tried different spellings for the Phiniminiiasis Syndrome you gave me yesterday. I exhausted the medical internet. I couldn’t find a thing.”

The group smiled and clapped their hands. Liscomb pointed to one of the residents to lead the discussion. The resident had obviously done this before. I listened to his words with my mouth open.

He stood up with a sense of authority, “Well, this happens to be one of those word-of mouth diseases passed down through the decades, but never really found a place in the medical literature. Phiniminiiasis includes our patient’s signs and symptoms. However, it’s an unusual condition that occurs only in a small percentage of separated Siamese twins. The one distinguishing factor seems to be a mis-alignment of the mouth and anus. As a result, other complaints by the patient are drooling during sleep and fecal staining in the underwear to one side or the other depending on the anal direction. The foul colonic gas is due to an abnormal balance of bacterial bowel flora. The treatment is self-administration of pro-biotic yogurt.”

Liscomb beamed as he pointed to the apparent error in my workup of the patient. “Dr. Glassman, it would seem your medical history was incomplete.”

I stared at him, “What do you mean incomplete?”

He had his hands on hips , “Obviously you should have asked her if she was a separated Siamese twin.”

The room rocked with their laughter, although, I failed to comprehend their amusement.

Liscomb shook my hand and told me I had passed the test.

I raised my palms, “What test?”

He seemed delighted in telling me that it was a test he gave to all new doctors on his service. He added that part of a doctor’s training is how to search the medical literature. A fictitious disease is given to the newest member and, since there’s no such clinical entity, the quest demands an effort to exhaust every resource.

To this day I remember his words, “You’ll be surprised how many interns and residents just give up after one textbook scan or one pass on the internet. You did well. You’re very thorough and credible.”

***

It’s no wonder I’ll never forget those syndromes when I’m creating fiction. Especially the history part. Researching a book’s habitat, colors, smells, and geography add to a reader’s sensorium. In addition, the politics, dates, music, and even clothes of a certain time period, help place characters in imaginable situations. They can also be tools to dissolve writers block.

Thorough and Credible. As an author, those words can help capture a reader. And like Phiniminiiasis, I find a place for the paranormal, fantasy, and even the outrageous which, backed up with even a minuscule of actual facts, is believable in a shadow of a doubt sort of way. I did this with my immigration terrorist thriller, The Druid Stone. Writer’s Block is in fact a syndrome common to authors. In my retirement as a fiction and non-fiction author, I’m definitely not above seeking help with my writing. Writer’s workshops, writer’s clubs, and paid professional help can change bumpy, vague, or non-connected thoughts to become smooth, moving verbiage. Finally, I fall back on a most important bit of advice learned from a Medical School Dean. “The definition of a good doctor is one who is not afraid of asking his colleagues for help.” The same goes for any author. It’s okay to get a second opinion and ask for help—as with participation in the Alamo City Writers Group, in San Antonio, Texas.

__________________________________

Peter Glassman is a retired physician living in Texas, who devotes his time to writing novels and memoir-based fiction. He is the author of 14 novels including the medical thrillers Cotter; The Helios Rain</em>; and Who Will Weep for Me. Some of his short stories were written for presentation at the San Antonio Writers Group Meetup. You can read more about him and his books here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast