Acid-Tinged Origins of Rock

by Michael Ray Fitzgerald (February 2023)

From England/The Who, Bonnie MacLean, 1967

Rock music soared into London and Los Angeles in the mid-1960s on a wave of Orange Sunshine. A year later it would make its home in San Francisco.

Despite the similarities in labels—and often being used interchangeably—the terms “rock” and “rock ‘n’ roll” are not the same thing.

The slang expression “rocking and rolling” originated in the black vernacular and referred to sexual intercourse. Early rock ‘n’ roll was upbeat blues for dancing, much of it saturated with sexual innuendo.

In 1951, Cleveland DJ Alan Freed converted the term into a noun and applied “rock ‘n’ roll” to blues-derived music with a big beat. In doing so, Freed took the music out of the ghetto and into the mainstream—for better or worse.

In 1951, Cleveland DJ Alan Freed converted the term into a noun and applied “rock ‘n’ roll” to blues-derived music with a big beat. In doing so, Freed took the music out of the ghetto and into the mainstream—for better or worse.

This music had emerged in the 1940s and exploded, thanks in part to Freed’s efforts, in the mid-1950s. It is generally associated with blues-based artists such as Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley. Presley performed some rock ‘n’ roll early in his career but gradually morphed into a straight-up pop act; none the less many people still refer to him as the king of rock ‘n’ roll (I would argue that Little Richard was the true king of rock ‘n’ roll, and his original version of “Tutti Frutti” beats Presley’s by a mile).

As Presley demonstrated with his first single on Sun Records in 1954, there was a strong country strain in the white iterations of this music—blues and country are closely intertwined and have been since the 1920s—foreshadowed by Hank Williams’ 1947 hit “Move It on Over,” which is a twelve-bar blues. Country group Bill Haley & the Comets’ 1954 hit, “Rock around the Clock,” is very similar if not identical to “Move It on Over.”

Muddy Waters explained, “the blues had a baby, and they named it rock ‘n’ roll.” However, the term “rock ‘n’ roll” shifted meaning when Freed and others began applying it to literally any type of music that targeted the burgeoning youth market.

The term has since been used—and abused—so loosely as to become meaningless. For example, in 1964, middle-aged British chanteuse Petula Clark managed to win a Grammy award for Best Rock ‘n’ Roll Recording, even though her song “Downtown”—or any of her music for that matter—never resembled any such thing.

Many people think of the Beatles as the ultimate rock ‘n’ roll group, but they didn’t actually perform all that much rock ‘n’ roll. Rather the group specialized in superimposing “big-beat” rhythms and arrangements featuring prominent drums and electric guitars over straight-up pop melodies. This experiment was most obviously effected in their 1961 rendition of the 1927 Tin Pan Alley hit, “Aint She Sweet.” (Singer Gene Vincent had conducted the same rhythmic experiment in 1956). To be fair, even though primarily a pop group, the Beatles could rock ‘n’ roll with the best of them, as evidenced by their renditions of Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” and “Kansas City.”

By the mid-1960s, the term “rock ‘n’ roll” had for the most part fallen out of general usage, and combos such as the Four Seasons, the Beach Boys and the Beatles were more often referred to as “beat” groups or simply “pop.” I was 11 when the Beatles and other British Invasion groups broke big, and I do not recall their being referred to as rock ‘n’ roll groups. Rock ‘n’ roll at that point—with the unlikely exception of Petula Clark—denoted Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Bill Haley, none of whom my pre-teen friends and I were familiar with.

Rock ‘n’ roll supplanted by “rock”

There came a crucial juncture in the mid-to-late 1960s when a new form called simply “rock” emerged. This was coterminous with the growing use of so-called mind-expanding drugs such as LSD along with the emergence of a youthful “counterculture” based on the expanded awareness these drugs ostensibly generated. “The acceptance of sexual freedom and increase in drug experimentation, specifically those that cause hallucinogenic, mind-altering experiences, became the essence of the hippie culture.”[1] This new rock music—also called “acid rock,” “psychedelic” and “underground music”—was not just an extension of rock ‘n’ roll but rather something entirely different. It was the soundtrack of this presumably illuminated counterculture.

Actually the LSD movement and its concomitant philosophy appeared prior to the music. Novelist Ken Kesey was a key figure of the emergent counterculture and personified the bridge from the “beat” movement of the 1950s to the “hippie” movement of the 1960s. While an undergrad at Stanford University near San Francisco, he volunteered for CIA-sponsored studies of LSD.[2] His 1960 novel, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, became a sort of manifesto of the LSD movement. Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters “dosed” people with the drug, and their Electric Kool-Aid Acid Tests brought San Francisco rock band the Grateful Dead into the psychedelic fold.

San Francisco was the home of 1967’s famous Summer of Love, a music festival held in Golden Gate Park, but psychedelia and acid-rock music had already been appearing in Los Angeles and even London.

When and where, specifically, did this new “rock” emerge? It’s hard to pin down. I would say the first openly psychedelic—that is, LSD-influenced—songs appeared about 1965 in London and Los Angeles. The Yardbirds’ “Heart Full of Soul,” released in mid-1965, featured a fuzz guitar that was actually imitating a sitar, an Indian stringed instrument. In fact the group had tried a sitar on the track but decided to go with the fuzz-toned guitar, performed by Jeff Beck, instead.[3] Distorted guitars became a hallmark of psychedelic music.

“Rock” incorporated a broad range of styles such as jug-band music, folk, country, music-hall, Vaudeville (“Winchester Cathedral,” “When I’m Sixty-Four”), Indian music, blues and even proto-heavy metal (Blue Cheer); in short it was anything hippies might listen to. Hence the term “rock” didn’t describe the music but rather the audience: It was the soundtrack for the hippie lifestyle.

The Beatles, already the most influential cultural force of the 1960s, underwent a drastic transformation after being “turned on” to LSD in March 1965 by a dentist friend and went from being a straight-ahead pop group to psychedelic mavens. Their musical transformation began on the group’s December 1965 album, Rubber Soul, with its eastern-influenced song, “Norwegian Wood”—which included a sitar played by guitarist George Harrison, who would himself begin a long association with Indian religion. Western youth’s interest in eastern music meshed with psychedelia.

The Beatles continued their evolution into fully-fledged psychedelia with “Tomorrow Never Knows” on their August 1966 album Revolver.

The Byrds, who had established themselves by applying a rock beat and electric guitars to folk music—rather like the Beatles had done with pop—was one of the early Los Angeles groups to experiment with psychedelia. It was David Crosby who introduced Harrison to Indian music during a Byrds tour of Britain.[4] The Beatles and the Byrds both continued to experiment with various and sundry styles, proving that “rock” was never any one thing.

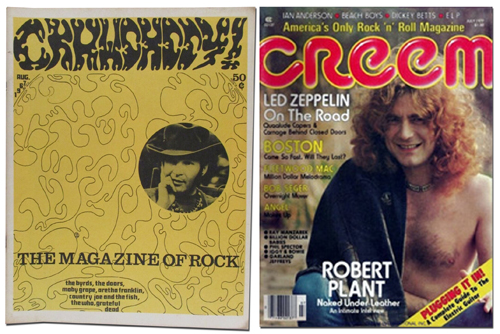

The concept of rock music was theorized and reified by music journalists at such publications as Crawdaddy!, Cheetah, Creem and Rolling Stone. Founded in February 1966 by 17-year-old Swarthmore College student Paul Williams, Crawdaddy! was “the first magazine devoted to the notion of rock as the crucial aesthetic medium through which the emergent counterculture articulated its dreams and aspirations.”[5]

The concept of rock music was theorized and reified by music journalists at such publications as Crawdaddy!, Cheetah, Creem and Rolling Stone. Founded in February 1966 by 17-year-old Swarthmore College student Paul Williams, Crawdaddy! was “the first magazine devoted to the notion of rock as the crucial aesthetic medium through which the emergent counterculture articulated its dreams and aspirations.”[5]

The new music communicated the values of the counterculture, which tended to eschew the middle-class morals and conspicuous consumerism of its parents. Music historian Jason Newman writes, “The counterculture stamped the rock-music explosion with its more salient features: a rejection of traditionalism, complacency and social mores.”[6]

In the early days rock was also referred to as “underground music,” but that rubric became inane in the 1970s when it went mainstream. Also there was an unlikely convergence of pop and rock called, obviously, “pop-rock,” of which the Beatles had been prime proponents if not progenitors. “Power pop” was another name for this hybrid style. This included groups like Beatles proteges Badfinger and Beatlesesque groups such as Cheap Trick and the Knack, who straddled both—seemingly disparate—worlds.

Rock music, dominated by electric guitars and drums, became the sound and style of youthful rebellion. It lasted for generations. Its purpose was to challenge and annoy parents. It was eventually surpassed in popularity by an even-more rebellious style called hip-hop.

But rock’s not dead yet—it just smells funny.

Early Rock Tracks, 1965-1968

Also See:

M. Curtis, Rock Eras: Interpretations of Music and Society, 1954–1984. Madison: Popular Press, 1987.

Richard Meltzer, Aesthetics of Rock. New York: Something Else Press, 1970.

Marc Woodworth and Robert Boyers, “Rock Music & The Culture of Rock: An Interview with James Miller,” Salmagundi 118/119, Spring 1998, 206-223.

Peter Wicke and Rachel Fogg, Rock Music: Culture, Aesthetics and Sociology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Paul Williams, The Crawdaddy Book. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard, 2002.

Notes:

[1] Music around the World: A Global Encyclopedia [3 volumes], Andrew R. Martin, Matthew Mihalka (eds.), Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2020, 751.

[2] University of Virginia Library, “The Psychedelic Sixties,” n.p, n.d. https://explore.lib.virginia.edu/exhibits/show/sixties/walkthrough/kenkesey

[3] Martin Power, Hot Hired Guitar: The Life of Jeff Beck. London: Omnibus Press, 2011.

[4] Ian Whitcomb, Rock Odyssey: A Chronicle of the Sixties. New York: Limelight Editions, 1994, 218.

[5] Simon C.W. Reynolds, “Rock Criticism,” Encyclopedia Britannica, n.p., n.d, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Rock-criticism-1688526#ref709937.

[6] Jason Newman, “Rock and Roll.” In American History. ABC-CLIO, 2000.

Table of Contents

Michael Ray Fitzgerald, PhD, is a media historian, former university instructor and musician. He is the author of the award-winning book, Jacksonville and the Roots of Southern Rock, from University Press of Florida.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast