By Daniel Mallock (January 2019)

Union and Confederate Veteran, 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, 1938

With the new year upon us we ought to look ahead with wisdom, forbearance, and caution. One of the best ways to look ahead is to look backwards at the same time. (Yes, I know this is counter-intuitive.)

Over the last decade, identity politics has done great harm to our country. There is now no reason to suggest that this damage will be minimized in the coming year. One of the two great political parties of the country embraces this destructive anti-American ideology, the other fights against it. It is the deconstruction of American Identity into disparate elements. It is at the very heart of the maelstrom of confusions and mislearnings that drives a large coterie of the American public.

The Civil War has been in the public eye in recent years as many Confederate monuments and memorials have been vandalized, destroyed, and brought down in large part as a sop to the demands of Identity Politics people. Too many on the American political left now embrace a new and bitter self-righteous anger that the survivors of the Civil War and the generations that followed them would not recognize nor countenance. It is a sort of destructive moral arrogance and self-obsession when people reject the reconciliations of past generations as if to say, “forgiveness may have worked for you, then, but for us, now, it has no application and is not relevant.”

The Civil War came in large part due to the identity politics of the past—sectionalism and the identification with state rather than with the union of all the states. The founders feared sectionalism with good reason, and hoped that future generations would resolve the problem; their hopes were disappointed. [There were a number of causes of the Civil War. There is a wide body of literature regarding this issue and as many opinions. Among the causes were slavery, sectionalism, southern anger at tariffs, and the rise of southern nationalism. Fundamental however to secession was the idea that the Union itself had failed, and that the Republic was therefore no longer worthy of support. The unifying national identity of “American,” under intense pressure from southern secessionist radical “fire eaters” for decades before the war began, finally collapsed.]

That one section was slave-holding and the other free exacerbated the problem to such an extent that finally the Union itself was broken, and the war came. The identity politics of today has its own broken logic and bitter justifications all centered around the supremacy of sub-groups/sub-identities over the essentialist and unifying supra-identity of “American.” The dangers that the politics of identity present to the future of the country are difficult to exaggerate.

Every president in American history emphasized time and again the importance of a unifying national identity, particularly after the Civil War. There has been but one exception to this unwritten presidential rule.

Read More in New English Review:

Modern Architecture’s Disastrous Legacy

Metaphysical Vacuum Cleaner

Baby Steps Toward the Abyss

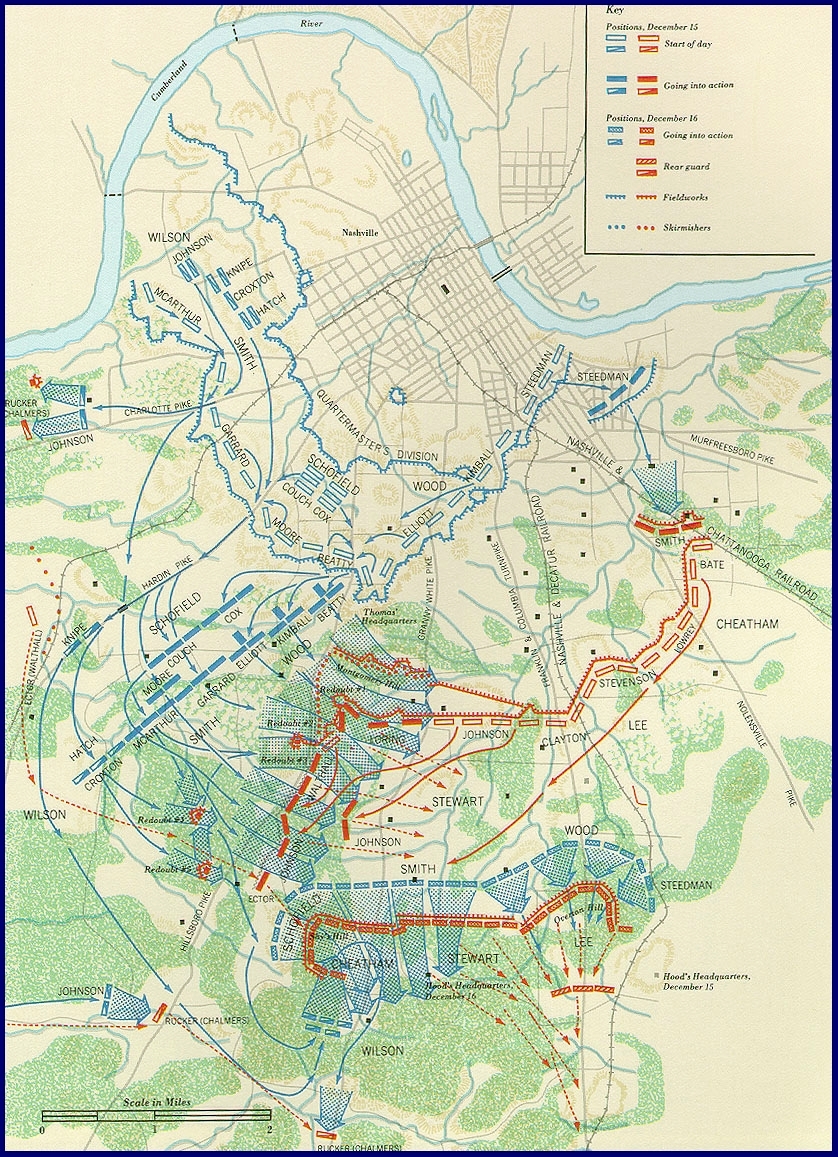

The battle of Nashville (Dec. 15/16, 1864) signaled the end of the Civil War in the West, and the end of the Confederate Army of Tennessee. After two days of significant fighting in the environs south of the city, the southern army, outnumbered, outgunned, and outmaneuvered, was defeated in one of the few decisive battles of the war. After Nashville, the Army of Tennessee retreated out of its namesake state and was effectively destroyed as a fighting force.

James Fowler Rusling (L), a New Jersey native and Chief Assistant Quarter Master of the Department of the Cumberland, survived the battle. His book, “Men and Things I Saw in Civil War Days” (New York, 1899) is both exciting and instructive reading for the modern American.

James Fowler Rusling (L), a New Jersey native and Chief Assistant Quarter Master of the Department of the Cumberland, survived the battle. His book, “Men and Things I Saw in Civil War Days” (New York, 1899) is both exciting and instructive reading for the modern American.

Rusling relates a story of the end of the second day of the battle of Nashville, December 16, 1864, during the calamitous retreat of the Army of Tennessee. The left flank of the Confederate battle line on the second day at Nashville was anchored on a hill called Compton’s, after the battle called Shy’s Hill. Significantly outnumbered the Confederates were overwhelmed when Shy’s Hill was assaulted from front, left, and rear after a harsh and accurate artillery barrage on the position. The entire Confederate line collapsed from left to right sending the Army of Tennessee in desperate retreat south.

The first day’s battle is shown in the middle of the map, the second day at the bottom. On December 16th late in the afternoon, the Confederate line collapsed by the left flank as Shy’s Hill was overrun from front, rear, and left. A general collapse of the Army of Tennessee began as Union assaults along the entire line followed the breach on the left. After Nashville, the Army of Tennessee was essentially destroyed as a fighting force. (Battle of Nashville Preservation Society)

The 5th and 9th Minnesota assaulting Shy’s Hill, December 16, 1864. This 1906 painting by Howard Pyle hangs in the Governor’s Reception Room of the Minnesota State House. Earlier in the day USCT (United States Colored Troops) soldiers vigorously assaulted the Confederate right at Peach Orchard Hill (Overton Hill). The courage and sacrifice of these black American soldiers ended the debate once and for all about the viability of black soldiers in the United States army. (For more information please see Battle of Nashville Preservation Society and Minnesota Historical Society)

Descendant’s Memorial Wreath, Shy’s Hill. (Courtesy of Battle of Nashville Preservation Society.)

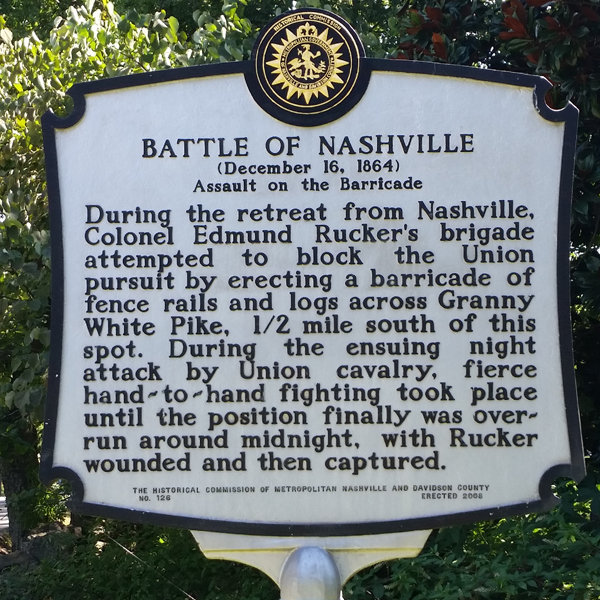

As the Confederate army disintegrated before attacks along the entire front, attempts were made (largely unsuccessful) to rally the panic-stricken southern soldiers. At one point, near where Granny White Pike now intersects with Old Hickory Boulevard, a force of Confederate cavalry stood their ground to provide time for the retreating army to escape. Essentially, the purpose of the cavalry action that transpired there was to save the army from total destruction and capture. The fighting was hand-to-hand in the almost complete blackout of a rainy December night. The darkness was so dense that the combatants could not differentiate friend from foe; the term “mayhem” does not do justice to the ensuing combat, but it’s close.

Historical marker on Granny White Pike, Brentwood, Tennessee.

After placing an Alabama cavalry regiment in position to block access to the Pike (and the retreat route to Franklin Pike) and to oppose a Union assault, Confederate Colonel Edmund Rucker spurred his horse into a group of riders whose identity he could not discern in the darkness. Approaching one man Rucker asked him who he was. The man responded that he was George Spalding, Colonel of the 12th Tennessee Cavalry (US). Rucker grabbed Spalding’s rein and shouted, “Well, you are my prisoner, for I am Colonel Ed Rucker, commanding the 12 Tennessee Rebel Cavalry!” Spalding pulled away shouting, “Not by a damned sight.”[1]

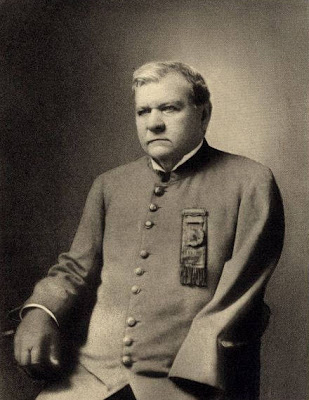

A running melee began around the two colonels as others became engaged in this very personal combat with swords on horseback in the pitch-black rain. A shot was fired at Rucker and he was struck in the sword arm, thus dropping his sword and the reins. Spooked, Rucker’s horse reared and the rebel Colonel was thrown to the ground. He was quickly captured and marched to the Union rear. Later, he would lose the wounded arm.

Rucker (L, after the war) was taken to Union cavalry commander James Wilson’s tent where he was treated with great courtesy by Generals Hatch and Wilson, Hatch in fact surrendering his bed so that the wounded Rucker could be comfortable. Such was the common chivalry between the soldiers of North and South (when they weren’t killing one another). These small events of consideration, such as the one experienced by Rucker after his wounding and capture, were the foundations of later reconciliation between the sections.

Rucker (L, after the war) was taken to Union cavalry commander James Wilson’s tent where he was treated with great courtesy by Generals Hatch and Wilson, Hatch in fact surrendering his bed so that the wounded Rucker could be comfortable. Such was the common chivalry between the soldiers of North and South (when they weren’t killing one another). These small events of consideration, such as the one experienced by Rucker after his wounding and capture, were the foundations of later reconciliation between the sections.

Colonel Rucker was not the only senior Confederate officer to be captured as the Army of Tennessee disintegrated just south of Nashville on the 16th of December, 1864. Among the prisoners were four Confederate brigadier generals two of whom dined with Rusling’s mess that evening. “We found them penniless, our boys having ‘gone through’ them when captured, as usual on both sides. We tendered them loans, which they gratefully accepted; and, subsequently, when the war was over, they both repaid the money duly. Of course, after all, they were yet American soldiers and gentlemen.”[2]

One of the great lessons of the Civil War, now apparently forgot or ignored, is about identity. The war was understood by most participants as a conflict within the American world, that is, an internecine conflict between Americans. Some later historians attempted to suggest that the Confederacy was representative of a new nation, a new people, a new national identity that had sprung up since the founding of the United States. This concept was fostered by Confederate leadership to justify secession/independence and was later resurrected to explain, in some fashion, the nightmare that was the war; it is not a position easily supported.

Rusling was not alone in viewing his Confederate enemies as fellow Americans who’d gone “off the rails” so-to-speak. It should come as little surprise that Fort Rucker in Alabama is named after Confederate Colonel Edmund Rucker, wounded and captured at Nashville. Numerous US Army facilities were named after Confederate officers as a sign of respect and reconciliation after the war. Fort Hood in Texas is named after General John Bell Hood, commander of the Army of Tennessee at Nashville, for example. There are many such US military posts named after Confederates.[3]

The heated sectional identity emotions of the Civil War gave way to post-war forgiveness and reconciliation. Some Americans are reigniting old hatreds of identity, cancelling the lessons gained at such high cost by our forebears, ignoring the essential truths of the insights of the founders, embracing an extreme sense of backward-looking outrage, alienation, denialism and bitterness—it’s all dangerous, arrogant folly.

The Civil War was the great test of whether our country under one constitution with one national identity could survive. The experiment in American democracy almost failed.

It was understood from the beginning of the country that a nation built on political freedoms with an open society of free discourse required a single national identity, American, in order to survive the constant pressures of heated political disagreements.

Because of this appreciation of the critical necessity of an overriding American identity this concept was stressed by every American president since George Washington, until the election of Barack Obama. Had Mrs. Clinton been victorious in 2016 the process of deconstruction would have accelerated.

The current president once again champions this central truth—the only way that Americans can be united is by subsuming all other identity designations and seeing ourselves as Americans first and foremost. This is a lesson learned again and again in our history, and now devalued and ignored by identity politics proponents.

Some have suggested that the extraordinary divisiveness in American politics and culture, widely based on profound disagreements around concepts of identity, means that we are now in a “cold civil war.” There is much of value in this view.

It is difficult to ascertain motives in such a conflict—but it is clear that the ongoing deconstruction of the American national identity, a destructive, self-righteous and short-sighted view now so popular with many on the political left, will have catastrophic consequences.

Read More in New English Review:

How Fake News has Misrepresented the Yellow Vest Revolt in France

Bashir Visits Assad in Damascus

First as Tragedy, Then as Farce: How Marx Predicted the Fate of Marxism

For many Americans, World War One signaled the defining moment of reconciliation between North and South, as northern and southern military units fought together against a common enemy (in defense of the United States) for the first time since prior to the Civil War. Having experienced first capture, then occupation, then a great battle in their city and surroundings, the people of Nashville understood the symbolic value of the historical moment all too well. They commissioned a peace monument which was dedicated in 1927. It is a testimony to the cooperation of north and south in World War One, of the sacrifices of the dead at the battle of Nashville, and the tragedy of the Civil War.

The lesson of unity and reconciliation enshrined on the battle of Nashville monument are now almost fully demolished in recent years. The lessons of the monument must be relearned, and re-embraced.

The people of Nashville understood full well the catastrophe that was the Civil War; they understood that American identity was the essential element in American survival and success, and they were fully aware that loss of American identity in the future would mean new catastrophes and tragedies. It is one of the most important monuments on the North American continent.

We move toward the future and look back to the past; the way to resolve the conflicts of the present is to review those of the past—and learn from them.

On the north face of the battle of Nashville monument is this inscription; a recognition of the past, and a perpetual prayer for the future.

Oh, Valorous Gray, In The Grave Of Your Fate,

Oh, Glorious Blue, In The Long Dead Years,

You Were Sown In Sorrow And Harrowed In Hate,

But Your Harvest Today Is A Nations Tears.

For The Message You Left Through The Land Has Sped

From The Lips Of God To The Heart Of Man:

Let The Past Be Past: Let The Dead Be Dead. —

Now And Forever American!

The Battle of Nashville Monument, Nashville, Tennessee.

[1] Under the Old Flag: Recollections of Military Operations in the War for the Union, The Spanish War, The Boxer Rebellion, etc., By James Harrison Wilson, Volume 2, (New York and London, 1912), p.122.

[2] Men and Things I Saw in Civil War Days, by James Fowler Rusling, (New York, 1899), p.101.

[3] Camp Beauregard; Fort Benning; Fort Bragg; Fort Gordon; Fort A.P. Hill; Fort Hood; Fort Lee; Fort Pickett; Fort Polk; Fort Rucker.

__________________________________

Daniel Mallock is a historian of the Founding generation and of the Civil War and is the author of The New York Times Bestseller, Agony and Eloquence: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and a World of Revolution. He is a Contributing Editor at New English Review.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

.JPG)