An Incident of the Battle of Franklin

By Daniel Mallock (March 2018)

In a speech delivered at Nashville in 1887, Ohio Senator John Sherman, the younger brother of Union General William T. Sherman said: “The courage, bravery, and fortitude of both sides are now the pride and heritage of us all. Think not that I come here to reproach any man for the part he took in that fight, or to revive in the heart of any one the triumph of victory or the pangs of defeat . . . No man in the North questions the honesty of purpose or the heroism with which the Confederates maintained their cause, and you will give credit for like courage and honorable motives to Union soldiers, North and South.”[1]

The Scene is Set

.jpg) n the annals of our national catastrophe that was the Civil War, few battles surpassed that of Franklin, Tennessee, November 30, 1864 for instances of heroism, savagery, and bitter hand-to-hand combat. The last grand charge of a great army on the North American continent occurred there as the battle opened. Many know of “Pickett’s Charge” at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 3, 1863), but few today know of the charge of the Army of Tennessee at Franklin. At Gettysburg, 12,500 men in gray charged across an open front of one mile. Prior to the assault, the greatest artillery barrage of the war occurred to “soften up” the Union lines at the famous “clump of trees” on Cemetery Ridge.

n the annals of our national catastrophe that was the Civil War, few battles surpassed that of Franklin, Tennessee, November 30, 1864 for instances of heroism, savagery, and bitter hand-to-hand combat. The last grand charge of a great army on the North American continent occurred there as the battle opened. Many know of “Pickett’s Charge” at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 3, 1863), but few today know of the charge of the Army of Tennessee at Franklin. At Gettysburg, 12,500 men in gray charged across an open front of one mile. Prior to the assault, the greatest artillery barrage of the war occurred to “soften up” the Union lines at the famous “clump of trees” on Cemetery Ridge.

Unsuccessful, the Confederate brigades, broken and decimated, retreated as their expected support did not appear. Widely known as the “High Water Mark of the Confederacy,” the charge at Gettysburg would be overshadowed by an even more massive and desperate effort the following year at Franklin, Tennessee.

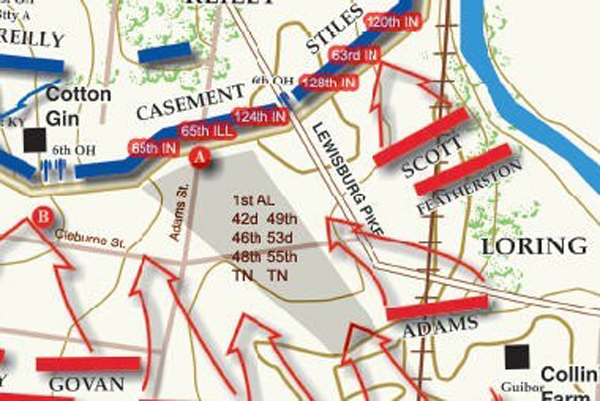

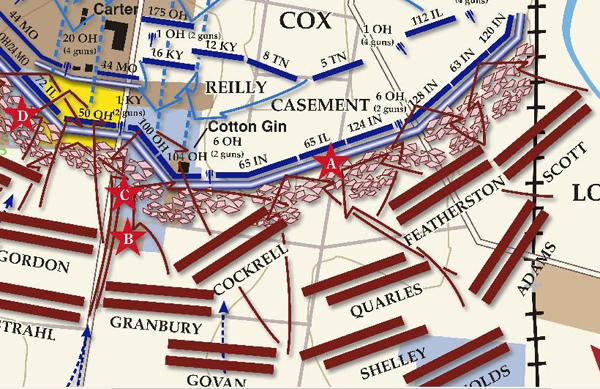

At Franklin, the majority of the 30,000 soldiers in the Confederate Army of Tennessee, over 100 regiments, lined up at the base of Winstead Hill some two miles south of the town.[2] With bands playing and flags dramatically flying, the Confederates charged two miles over open ground with no artillery “preparation” and minimal support, under Union cannon fire for most of the duration of the assault. The surgeon of the 22nd Mississippi wrote that Franklin “was the first and only time I ever heard our bands playing upon a battlefield and at the beginning of a charge.”[3] Beginning at around 4pm, most of the battle that followed was fought in the dusk and darkness of night finally concluding around midnight. An unfortunate and dramatic torch lit assault on the Union right around 7pm was driven back in disarray with heavy casualties. Known among survivors and later students as one of the most savage battles of the entire war—a conflict that included so many bitter battles—the Confederates made 13 separate charges against the main Union lines in front of the Carter House and Cotton Gin.

Battle map courtesy of Civil War Trust.

In the space of five hours, almost 10,000 men in blue and gray were killed or wounded (2,000 killed in action). The majority of the casualties were southerners. Five Confederate generals were killed at Franklin (Cleburne, Strahl, Gist, Adams, Granbury), another, General John Carter, mortally wounded, died ten days later. He is buried under a tree near the Duck River at Columbia, Tennessee.

.jpg)

Monument to John Carter, Brigadier General, mortally wounded at Franklin. This and other monuments to the Confederate generals killed at Franklin are located on the northern slope of Winstead Hill.

After the loss of Atlanta in July, 1864, the defeated Army of Tennessee eventually moved to northern Alabama to rest, reorganize, and prepare for the next campaign. The commander, General John B. Hood, formerly of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, knew that he could not successfully oppose Sherman’s massive army as it disengaged from its line of supply and began the devastating March to the Sea.[4] The President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, visited the camps of the Army of Tennessee on an inspection tour. He delivered a speech to elements of the Army on September 25, 1864, on his arrival in Palmetto, Georgia, where he addressed Cheatham’s division which included many Tennesseans. “Be of good cheer,” President Davis assured his troops, “for within a short while your faces will be turned homeward and your feet pressing the soil of Tennessee.”[5] Sherman learned of this presidential encouragement and Davis’s bellicose, defiant September 23rd speech in Macon, Georgia, [6] as well as another delivered in Augusta, Georgia two weeks later where he said the army would soon be “pushing on to the Ohio.”[7] Sherman came to the obvious conclusion that Hood planned to invade Tennessee and attempt to retake Nashville. The Union commander sent orders accordingly—General Thomas at Nashville to augment his forces by drawing as many troops as possible into the city, and General Schofield, then in southern Tennessee near Pulaski, to link up with Thomas.

Nashville was captured in late February, 1862, after U. S. Grant’s forces took Forts Henry (Tennessee River) and Donelson (nearby on the Cumberland River). By November, 1864, Nashville was the most heavily fortified of any city in the United or Confederate states. Sherman was betting that Schofield and Thomas would successfully defeat Hood’s plans. Before he could get to Nashville, however, Hood first had to defeat Schofield’s two army corps.

By early November, 1864, Hood led his army north. Awaiting him in southern Tennessee was John Schofield’s two Union army corps (commanded by David Stanley and Jacob Cox) with some 33,000 men. In Nashville waited George Thomas with an understrength army of occupation of some 18,000 Union soldiers. All were aware that Hood’s target was Nashville. A race against time between Hood and Schofield began. Schofield must get to Nashville and take safety within the works; Hood must destroy Schofield’s army before it can get to Nashville. If Schofield should be successful in getting to Nashville without, at least, significant damage, the disparity of forces would greatly diminish Confederate chances of success there. It should come as little surprise that Schofield and Hood were once West Point roommates.

Fifteen miles south of Nashville is the town of Franklin. At the time a small community with strong Confederate leanings and a population of 2,000 it would be the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. Thirteen miles to the south of Franklin is Spring Hill.

Map courtesy of Google maps.

After days of hard marching, Hood arrived in Spring Hill on November 29—mere hours before Schofield. The Army of Tennessee was in position to spring a deadly trap—a classic flank assault along the Columbia Pike that, if executed smartly, could result in the capture or destruction of Schofield’s entire army. Hood was on the verge of one of the greatest triumphs of the war. By early evening Hood issued orders to block the Columbia Pike and thus prevent the Union army from getting through to Franklin, then on to Nashville. Success at Spring Hill was essential if Nashville was to be assailed victoriously.

General John Bell Hood, commander of the Army of Tennessee.

As evening descended and thousands of Confederates stood several hundred yards from the pike waiting for orders to attack, they could hear the Union army marching past them in the darkness heading north along the road, their artillery and wagon wheels muffled to decrease the sound as much as possible. Schofield was desperately trying to escape the trap so carefully laid by Hood. Despite expectations of an imminent battle no order to attack ever came, though the army commander had issued such an order. Schofield escaped Spring Hill, rushing ahead to Franklin where entrenchments still existed from a previous battle there, and Fort Granger, an impressive artillery position that covered the southern approaches to the town, awaited him. But at Franklin another trap was also waiting for Schofield.

Major General John M. Schofield, US Army.

After heavy rains, the Harpeth River was swollen to almost flood levels and the bridges across the river (on the road to Nashville) could not easily accommodate his entire army for a rapid crossing. Once at Franklin, just hours ahead of the pursuing Confederates, with his back to the river, Schofield had to hold the town at all costs, or be destroyed. The old earthworks were rapidly strengthened and pitched higher, and a ditch dug in front. Obstructions were placed, and artillery pieces installed all along the line. With but a few hours to prepare, the Union army in Franklin successfully constructed formidable defenses.

The non-attack at Spring Hill has long been one of the great mysteries of the Civil War. Only recently was an explanation discovered. Two key senior officers of the Confederate Army of Tennessee had received Hood’s orders to attack but, deploring the idea of a night battle, they took no action and disobeyed the order.[8] No night battle at Spring Hill occurred and what could have been an extraordinary defeat for Schofield became for him, instead, a stroke of unexpected luck that likely saved his army. The following day however, some 13 miles north on the Columbia Pike (the road that Hood had ordered blocked at Spring Hill), a night battle did occur, and it was of such extraordinary savagery that survivors remembered it with horror.

Approaching the unexpectedly quiet Columbia Pike lines in the early hours of the morning from his headquarters a mile or so away, General Hood saw no maelstrom scene of a surrendering Yankee army at Spring Hill. Instead he saw an open road north, a resting gray army—and no Yankees. Hood immediately understood that his orders had not been followed, and the soldiers of the army also understood that their quarry had escaped them. The men in the ranks were angry and frustrated, the commanding general understandably “wrathy as a rattlesnake,” according to General John C. Brown (division commander in Cheatham’s Corps).[9] The Army of Tennessee rapidly pursued Schofield north along the Columbia Pike toward Franklin. Bitterly angry that they had allowed Schofield’s army to escape the trap at Spring Hill the Confederates, many of them Tennesseans from the area, were beside themselves with frustration. They were all determined to correct the errors of Spring Hill.

South of Franklin is a low range of hills called the Winstead Range. After cresting this small range along the Columbia Pike mid-afternoon of the day following the lost opportunity at Spring Hill, Hood and his top generals surveyed their front. They could see the main Union works two miles north centered on the pike, and an inexplicably exposed forward line about a mile and a half from them. (The exposed forward position with about 3,000 men was approximately 500 yards in front of the main Union line). If the Confederates could break the first line and drive those unlucky men in front of them, they might be able to break through the main line in the confusion of the retreating thousands. In their run for the Union main works the men in the exposed forward line would act as shields for the pursuing Confederates.

The calculus was this: the Confederates expected the Federals in the main line to withhold their fire as the men from the forward line fled back to the main line. Once the Confederate onslaught contacted and broke the inexplicably exposed position 500 yards in front of the main entrenchments, a life and death race to the firmly held Union entrenchments would begin. This was a self-evident strategy that the soldiers of both sides understood well.

The men in the forward line, digging their makeshift breastworks and watching the Confederates forming up for the charge, readily comprehended the impossibility of their position. “Column after column began to pour over the hills and down into the valleys and up through the ravines…” W.A. Keesy of the 64th Ohio wrote in his memoirs. “Our Colonel turned to us and said: ‘Now boys, we will hold this line at all hazards.’ This, of course, did not encourage us. In looking upon the army confronting us and coming upon us, it did not take a philosopher to see that to hold that line against such numbers was an utter impossibility.”[10]

One Confederate soldier wrote, of the decision to attack, that “it was all important to act, if at all, at once.”[11] When the gray lines formed up for the charge, it was already late afternoon. If the first charge succeeded, a general engagement at night might be avoided. The Union army could not be allowed to finish entrenching at the main line, it could not be allowed to escape Franklin and get to Nashville. Most of all, the debacle at Spring Hill had to be avenged. The attack must begin immediately.

All in the gray line at the northern base of the low hills of the Winstead Hill range understood what was to come; all in the Union lines furiously digging entrenchments and placing artillery pieces also knew.

What happened next would stun them all.

“Kind reader, right here my pen, and courage, and ability fail me. I shrink from butchery. Would to God I could tear the page from these memoirs and from my own memory. It is the blackest page in the history of the war of the Lost Cause,” Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee wrote in his exceptional memoir, “Company Aytch.” “It was the bloodiest battle of modern times in any war. It was the finishing stroke to the independence of the Southern Confederacy. I was there. I saw it. My flesh trembles, and creeps, and crawls when I think of it today. My heart almost ceases to beat at the horrid recollection. Would to God that I had never witnessed such a scene!

“I cannot describe it. It beggars description. I will not attempt to describe it. I could not. The death-angel was there to gather its last harvest. It was the grand coronation of death. Would that I could turn the page. But I feel, though I did so, that page would still be there, teeming with its scenes of horror and blood. I can only tell of what I saw.[12

Sam Watkins

The Only Trophy I Have of the Great War, November 30, 1864

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

—”For the Fallen” by Laurence Binyon

Have you forgotten yet?. . .

For the world’s events have rumbled on since those gagged days,

Like traffic checked while at the crossing of city-ways:

And the haunted gap in your mind has filled with thoughts that flow

Like clouds in the lit heaven of life; and you’re a man reprieved to go,

Taking your peaceful share of Time, with joy to spare.

But the past is just the same-and War’s a bloody game . . .

Have you forgotten yet?. . .

Look down, and swear by the slain of the War that you’ll never forget.

—”Aftermath” by Siegfried Sassoon

The literature of the Civil War is so extensive in large part because there were so many extremes—of fighting, sacrifice, loss, failure, success, tragedy, horror, waste, courage, and bravery. These are the things from which legends are made and they form the foundations of our American national story.

There are too many stories of incredible bravery and superiority of character and integrity from our Civil War that to do even a small number of the heroes in blue and gray the justice they merit is an impossibility. The libraries of Civil War history are full of such stories, small and epic tragedies and victories. During one of the most savage battles of that war on the outskirts of a small Tennessee town on November 30, 1864, more than enough stories of extraordinary people and actions were written to fill numerous volumes.

In this battle of several hours, most of it fought in the falling light of a mild, early winter evening and the moonlit darkness that followed, one particular event of such extreme bravery, courage, and character occurred that all who witnessed it on both sides were astounded and inspired.

The events of that late afternoon and evening; the savagery of the fighting, the compassion shown to the wounded, and the great respect that each side later showed the other all helped to re-unite the sections when the war finally closed less than a year later.

Years after the battle Confederate General Frank Cheatham (a Confederate Corps commander at Franklin) told one Union veteran visiting Nashville, “Any man who was in the battle of Franklin, no matter which side, is my friend.”[13] The fighting at Franklin was so vicious and the losses so high that when Cheatham, known as a tough soldier, was told of the devastating casualties he burst into tears.[14] When the morning light finally exposed the horror of the scene Cheatham, in a post-war interview, described the battlefield as “such a sight I never saw and can never expect to see again… You could have walked all over the field upon dead bodies without stepping upon the ground… It was a wonder that any man escaped alive… I never saw anything like that field, and never want to again.”[15]

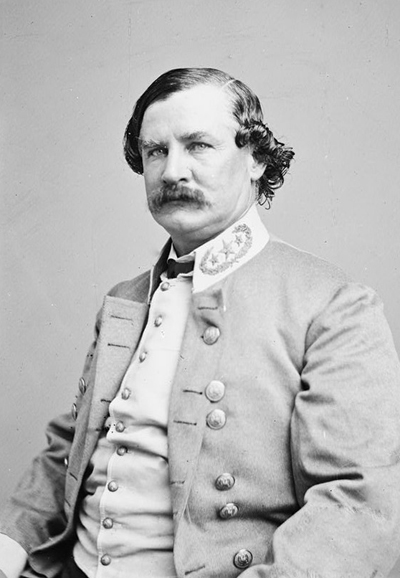

Major General Frank Cheatham, CSA

Brigadier General John S. Casement, a Union brigade commander from Ohio kept only one trophy, one relic from his entire war service. Decades later, Casement returned this trophy to the widow of the enemy general killed in his brigade front at Franklin, Tennessee, many years before.

What follows is the story of bravery so extraordinary that, for a time, over the screams and din of close quarter combat near the Carter Cotton Gin could be heard other cries, “Don’t kill him! Do not shoot that man!”

Brig. Gen. John S. Casement, USA

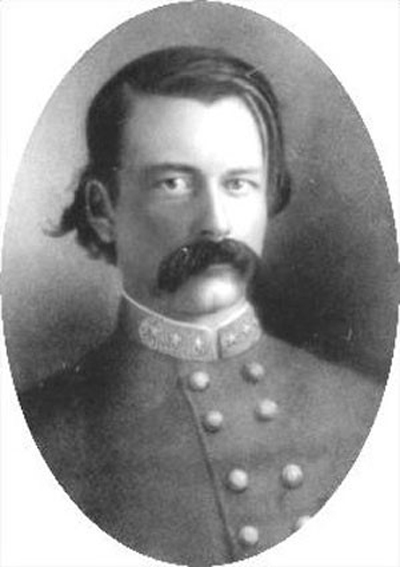

When the order to advance was given around 3:30pm on November 30, 1864, two miles south of the little town of Franklin, Tennessee, Brigadier General John Adams (b. 1825) was commanding his brigade of Mississippians from horseback. The last grand charge on the North American continent was beginning.

Brig. Gen. John Adams, CSA

As he prepared for the assault General Patrick Cleburne viewed the scene from Winstead Hill. “Well, General, few of us will ever return to Arkansas to tell the story of this battle,” Daniel Govan, Cleburne’s subordinate heavily said. Cleburne replied with a sentiment that was prevalent throughout the gallant Army of Tennessee: “Well, Govan, if we are to die, let us die like men.” Several years ago, a memorial pyramid of cannon balls was placed at the spot where Cleburne was killed directly in front of the Carter Cotton Gin, close by to the Columbia Pike.[16] General Govan, a brigadier in Cleburne’s division, survived the battle.

Carter Cotton Gin, looking north on the Columbia Pike.

The scene was extraordinary. Some of the men in blue two miles away and closer still were astounded at the sight. Levi Scofield, watching from the exposed forward Union line described what he saw:

It was a grand sight! Such as would make a lifelong impression on the mind of any man who could see such a resistless, well-conducted charge! For the moment we were spellbound with admiration, although they were our hated foes; and we knew that in a few brief moments, as soon as they reached firing distance, all of that orderly grandeur would be changed to bleeding, writhing confusion, and that thousands of those valorous men of the South, with their chivalric officers, would pour out their life’s blood on the fair fields in front of us. As forerunners well in advance could be seen a line of wild rabbits, bounding along for a few leaps, and then they would stop and look back and listen, but scamper off again, as though convinced that this was the most impenetrable line of beaters-in that had ever given them chase; and quails by the thousands in covies here and there would rise and settle, and rise again to the warm sunlight that called them back; but, no, they were frightened by the unusual turmoil, and back they came and this repeated until finally they rose high in the air and whirred off to the gray skylight of the north.[17]

The grandeur of such extraordinary things is fleeting . . . they were all, to a man—on both sides—regardless of the impressive martial display ready to get down to the ugly, violent business at hand. Nathan Bedford Forrest, commanding the cavalry assault on the far Confederate right had once said, “War means fighting, and fighting means killing.”[18]

Site of the death of Maj. General Patrick Cleburne, Cotton Gin front, Franklin, TN.

Adams’s brigade was on the far right of the infantry line trudging across open country and farm fields under artillery fire the entire two-mile distance. On their advance to the Union main line, they passed Carnton, a lovely southern mansion owned by the McGavock family. Many of his men were killed and wounded in Carnton’s yards and fields; the stately house quickly became a field hospital. Much like General Richard B. Garnett, a Confederate division commander at Gettysburg, Adams recklessly and courageously led his infantry from horseback.[19] Adams’s Mississippi brigade approached the Union works and were stopped by a barrier of sharpened Osage orange tree branches placed there to impede them. With their spiny thorns and the thickness of the brush combined, the momentum of the massive Confederate assault stalled. Under a withering fire from their front and from artillery batteries on their flanks (including the guns of Fort Granger across a bend in the Harpeth River to their right that Forrest tried unsuccessfully to silence) they struggled to open paths through the obstructions. Though wounded in the upper right arm during the assault Adams refused to leave the field, telling an aide, “No, I am going to see my men through.”[20] Several hours later almost 500 men in his brigade were casualties.[21]

“A” is the location of General Adams’s death.

Seeing the obstructions ahead, Adams rode his horse rapidly across his brigade front from right to left, instructing his men to oblique to the left to find an easier path to assail the Federal entrenchments. This movement put General Adams just in front and to the right of the Carter Cotton Gin.

A Union regimental commander veteran of the battle, in conversation with General Cheatham years later at a Southern Historical Society meeting in Louisville, Kentucky, said, “If General Adams had made the attack on your (the Confederate) extreme left, he would have carried the works and Nashville would have been yours without a battle.”[22] Such “what-ifs” are now only for the wargamers and arm-chair historians to ponder.

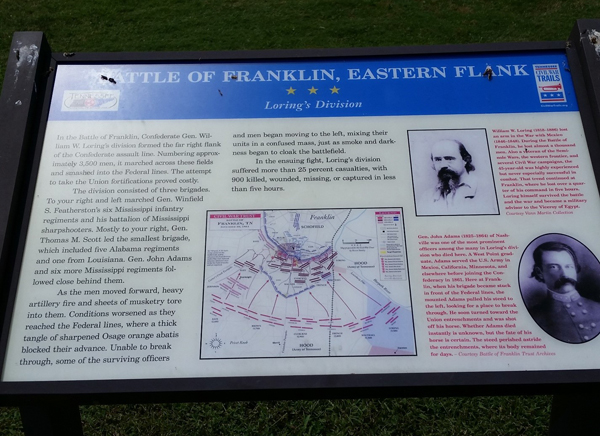

Marker on the Eastern Flank at Franklin, Adams’s approach to the main Union line.

Shouting for his men to follow, inspiring them with his conspicuous bravery, Adams spurred his warhorse “Old Charley” directly for the Union works in front of the Carter Cotton Gin. Federal soldiers in this section of the line, Casement’s men from Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois later reported nine Confederate charges against their position.

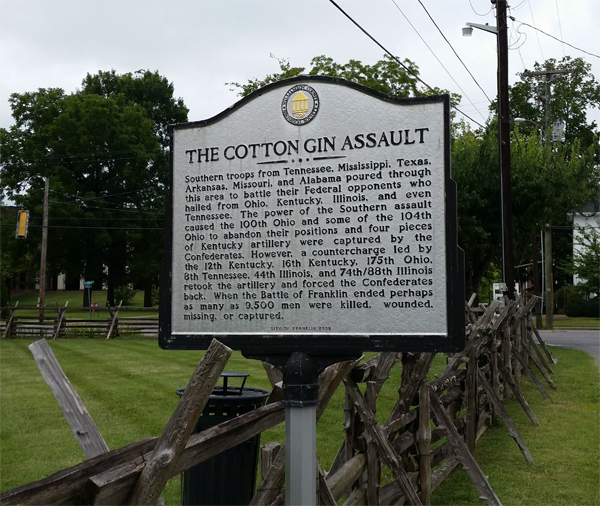

Historical marker near site of Patrick Cleburne’s death, in front of the Cotton Gin.

“At Franklin there was not a more natural or sublimer display of true heroism than was made by Brigadier-General John Adams, a Tennessean, commanding a brigade in Loring’s division, Stewart’s corps,” Lt. General A. P. Stewart said of General John Adams. “It was natural because it emanated spontaneously from one whose very nature was heroic and who, consequently, could not act otherwise than heroically.”[23]

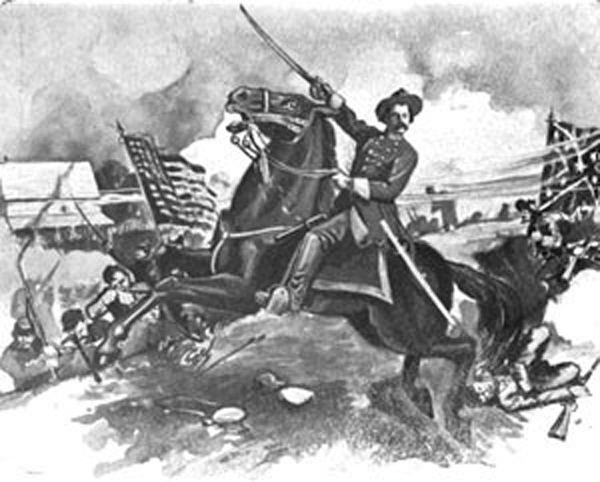

Adams and Old Charley at Franklin.

Leaping “Old Charley” to the top of the works (six feet high by most accounts) Adams yelled for his men to follow and take the entrenchments. Stunned by Adams’s bravery and audacity, some Union soldiers shouted, “Do not kill him! Do not shoot that man!” Adams was born in Nashville and lived nearby in Pulaski. His long history in the US Army from West Point, the Mexican War, frontier wars, and then in the Confederate service was coming to its extraordinary climax.[24]

From atop his war horse above the Federals in their works, he lunged for the national flag of the 65th Illinois Volunteers. Shot nine times Adams tumbled from his horse, mortally wounded. Old Charley, also struck numerous times, fell dead on top of him, pinning Adams immobile on the Union entrenchment.

“Our Colonel Stewart . . . called to our men not to fire on him, but it was too late,” James Barr, of the 65th Illinois, wrote. “Gen. Adams rode his horse over the ditch to the top of the parapet, undertook to grasp the ‘old flag’ from the hands of our color sergeant, when he fell, horse and all, shot by the color guard.”[25]

“We looked to see him fall every minute, but luck seemed to be with him. We were struck with admiration . . . He was too brave to be killed. The world had but few such men . . . ” Colonel Tillman Stevens of the 65th Indiana wrote. “We saw scores of officers fall from their mounts . . . but the one great spirit who appealed the strongest to our admiration was Gen. John Adams . . . He was riding forward through such a rain of bullets that no one had any reason to believe he would escape them all, but he seemed to be in the hands of the Unseen, but at last the spell was broken and the spirit went out of one of the bravest men who ever led a line of battle.”[26]

Another Union officer survivor of the battle whose name is not known to history described what he saw to James Porter, a former member of Cheatham’s staff, at a post-war event in Louisville. “His (General Adams) conduct at Franklin was the grandest performance of the war,” the officer told Porter. “I watched him as he led his brigade against our works. He looked like a soldier inspired with the belief that the fortunes of his cause depended upon his own actions; and when his horse leaped upon our works for one moment there was a cessation of firing, caused no doubt, by admiration of his lofty courage.”[27]

As they continued to defend their position against repeated Confederate charges, Union soldiers took the mortally wounded general from under his dead horse, Old Charley’s forelocks hanging over the Union side and hind legs over the other. It was clear that Adams could not live long.

The Indiana and Illinois soldiers brought him behind their lines a short way. Made as comfortable as possible, with his head on a pillow of cotton from the nearby cotton gin, he requested to be sent back to the Confederate lines. But this was a luxury the Federal soldiers couldn’t afford to give as the fierce fighting around them made any such transfer impossible.

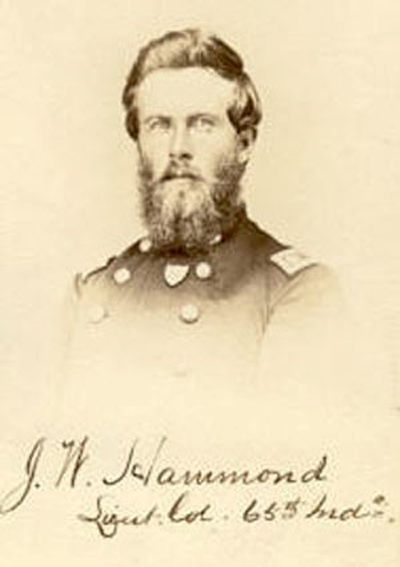

Lt. Colonel Hammond, a senior officer of the 65th Indiana.

“As soon as the charge was repulsed our men sprang upon the works and lifted the horse, while others dragged the General from under him. He was perfectly conscious, and knew his fate,” Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Adams Baker, of the 65th Indiana wrote. “He asked for water, as all dying men do in battle, as the life blood drips from the body. One of my men gave him a canteen of water, while another brought an arm load of cotton from an old gin nearby and made him a pillow. The General gallantly thanked them, and, in answer to our expressions of sorrow at his sad fate, he said: ‘It is the fate of a soldier to die for his country,’ and expired.”[28]

The ill-fated advance, and the desperate bloody charges had no discernable effect but the killing. The Union army withdrew from their lines around 11:30pm, crossed the Harpeth River in their rear and marched for Nashville in the chill darkness of the first day of December, 1864. The once mighty Army of Tennessee had broken itself on the earthworks south of Franklin.

When General Hood left his headquarters at the Harrison house some 2.5 miles from the front and approached the empty Union entrenchments in the early hours of December 1st, after all the charges had ceased and the guns fallen silent, the situation at first appeared to suggest a Confederate victory. As the appalling carnage of the fighting came into view, it quickly became clear to the Commanding General that the cost of Franklin had been extraordinarily high and, despite the sacrifice, Schofield had escaped to Nashville. Surveying the thousands of dead and wounded on the battlefield, the commander of the Army of Tennessee sat on his horse and “wept like a child.”[29]

The pursuit began almost immediately. General Hood, in his posthumously published memoir, “Advance and Retreat,” described his decision to advance to Nashville despite the high casualties at Franklin. “I could not afford to turn southward, unless for the special (emphasis in original) purpose of forming a junction with the expected reinforcements from Texas, and with the avowed intention to march back again upon Nashville,” General Hood wrote. “In truth, our Army was in that condition which rendered it more judicious the men should face a decisive issue rather than retreat-in other words, rather than renounce the honor of their cause, without having made a last and manful effort to lift up the sinking fortunes of the Confederacy. I therefore determined to move upon Nashville, to entrench, to accept the chances of reinforcements from Texas, and, even at the risk of an attack in the meantime by overwhelming numbers, to adopt the only feasible means of defeating the enemy with my reduced numbers, viz., to await his attack, and, if favored by success, to follow him into his works.”[30]

Two weeks later the campaign ended in disastrous defeat at Nashville. On their retreat south, the Confederates crossed over the nightmare battlefield of Franklin once again, the carcass of Old Charley still on the Union works.

When Adams’s body was recovered that of General Patrick Cleburne was also found, some fifty yards away in front of the Cotton Gin. There was a single bullet hole in his chest. Placed in the same ambulance it traversed the ground that Adams had charged across on Old Charley on its way back to Carnton. At the bustling field hospital that Carnton had become, they were placed on the lower porch of the house. What a scene: the killed-in-action Confederate Generals Patrick Cleburne, Otho Strahl, John Adams, and Hiram Granbury laid out beside each other on the first-floor main porch of Carnton, where hundreds of their comrades were fighting for their lives in and around this antebellum mansion. Its floors stained with the blood of the dead and dying, the amputated limbs of the wounded in piles thrown outside the windows of first floor rooms converted to operating theaters, Carnton was rapidly transformed from sleepy, stately home to a desperate aid station and morgue.

Confederate Cemetery at Carnton. (Photo by Robin Hood)

After the slaughter at Franklin and the disaster at Nashville, General Hood offered his resignation to President Davis. His petition rejected, Hood was instead sent to Texas for recruiting duty in 1865 to raise a new Confederate army which never materialized. He was one of the last Confederate commanders to surrender, May 31, 1865.

In the months following the battle at Franklin the cannons across North and South all fell silent, and the gray war dead inexpertly buried on the field were reinterred at the Carnton Confederate Cemetery.[31]

In 1891, Lt. Col. Baker of the 65th Indiana wrote a detailed letter to John Adams’s widow inquiring as to his character, and providing her with his recollection of the circumstances of the general’s death at Franklin.[32] Colonel Baker described the General’s bravery and the disposition of his personal effects, including his saddle, which had been given to General Casement, then living in Painesville, Ohio. Baker concluded his letter by inviting Mrs. Adams’s sons to visit him and informing her that he would communicate to General Casement regarding the saddle if she requested it. Colonel Baker’s is an extraordinary letter; General Casement’s letter to Adams’s widow continued the theme.

General Adams’s saddle. It is the standard Confederate cavalry “Jenifer” design.

Painesville, Ohio.,

November 23, 1891

Mrs. Georgia McD. Adams.

Dear Madam: Major Baker, of Webb City, Mo., informs me that you have expressed a desire to obtain the saddle used by General Adams at Franklin, Tennessee, in his last and fatal ride on the unhappy day that caused so many hearts to bleed on both sides of the line. It was my fortune to stand in our line within a foot of where the General succeeded in getting his horse’s forelegs over the line. The poor beast died there, and was in that position when we returned over the same field more than a month after the battle. The saddle was taken off the horse and presented to me before the charge was fairly repulsed; that is why I have kept it all these years. It is the only trophy I have of the great war, and I am only too happy to return it to you. It has never been used since the General used it. It has hung in our attic. The stirrups were of wood, and I fear that my boys in their pony days must have taken them, for I cannot find them. I am very sorry for it. General Adams fell from his horse from the position in which the horse died, just over the line of the works, which were part breast-works and part ditch. As soon as the charge was repulsed I had him brought on our side of the works, and did what we could to make him comfortable. He was perfectly calm and uncomplaining. He begged me to send him to the Confederate line, assuring me that the men that would take him there would return safe. I told him that we were going to fall back as soon as we could do it safely, and that he would soon be in possession of his friends. It was a busy time with me. Our line was broken from near its center up to where I stood in it, and in restoring it and repulsing other charges I was too busy to again see the General until after his gallant life had passed away. I had his ring and watch taken care of; his pistol I gave to one of the Colonels of my brigade, and do not know what became of it. These are briefly the facts connected with the death of General Adams. The ring and watch were sent to you through a flag of truce and a receipt taken for them. The saddle will be expressed to you tomorrow. Would that I had the power to return the gallant rider! There was not a man in my command that witnessed the gallant ride that did not express his admiration of the rider and wish that he might have lived long to wear the honors that he so gallantly won. Wishing you and his children much happiness,

I am yours truly, J. S. Casement[33]

The fight at Franklin was brutal, bloody, and costly. Though the battle there was often discussed at veteran gatherings, private and public, as being special in its own horrific and gory way, a National Battlefield Park was never created there; no commemorative arch across Columbia Pike between the Carter House and Cotton Gin was built as was suggested by one speaker at the 1909, 45th anniversary of the battle.[34] By then, the Union emplacements where Adams and Cleburne and so many others were killed were gone and homes built in their place; Franklin slowly reverted back to the growing picturesque small southern town that it had been before the war arrived there with a vengeance.

However, other movements are now afoot in Franklin to save the remaining portions of the battleground and properly commemorate the extraordinary events that occurred there. Indeed, the Carter Cotton Gin will be rebuilt, and Franklin, Tennessee will likely rise toward the top of the list of Civil War history destinations.[35]

In America, we seem constantly at war with ourselves—pulled backwards by the past yet propelled always into the future. Despite the wishes of loud minorities to eradicate elements our history that some find unpleasant or too difficult to accept we cannot escape our past, nor should we try.

The Confederates killed at Franklin repose in ordered rows at Carnton’s Confederate Cemetery, the tourists come and go. The cemetery is neat, clean, and appropriately quiet; it is a tribute to the men interred there as well as to those who tended their graves over the generations and continue to do so. “You are not forgotten” the flowers on the mainly anonymous stones symbolically say. The house close by is alive now and continues to honor the promise and efforts of Carrie McGavock who selflessly nursed the many wounded in her home (some for months after the battle), then cared for the cemetery until her death.[36] She earned the undying appreciation of Confederate veterans for her tireless and humanitarian efforts.[37] Carnton is now the anchor of the impressive “Eastern Flank Battlefield Park.”[38]

Now, one can rent Carnton for wedding parties; the beauty and hopes of life are mixed with the violence and horrors of the past. The porch where the bodies of Cleburne, Adams, Strahl, and Gist were laid out remains—now visitors stroll there, and musicians serenade happy event guests. The one-time small town of Franklin is embracing its dark, proud, and extraordinary history, and people from across the world visit there.

We cannot forget the horror and the sacrifice, the honor, and the bravery of those men in blue and gray just as we must not forget that those once at war became brother Americans again. That the nation survived the catastrophe of civil war is an essential lesson.

The divisive issues that sundered the country then are resolved and the sections unified. A wave of forgiveness and unity brought the country together by the turn of the century in large part due to the efforts of the veterans themselves. The great tragic war that killed over 700,000 Americans is now a matter of historical record, though it continues to be debated and generate strong emotions. After the war there was little desire in Tennessee to commemorate the horrific battle of Franklin. Time does not heal all wounds, though it does allow future generations to look back in amazement and awe.

Carnton, Franklin, Tennessee.

[1] The Century magazine, 1887, v.34, p.310 fn.

[2] Please see Civil War Trust for numbers engaged and casualty figures. (https://www.civilwar.org/learn/civil-war/battles/franklin) [accessed January 1, 2018]. It should be noted that the entirety of the Army of Tennessee was not involved in the charge at sunset, but over 20,000 were.

[3] Dr. Phillips, Surgeon, 22nd Mississippi, “Eyewitnesses at the Battle of Franklin,” (Nashville, TN, 2000), David Logsdon, Editor, p.13.

[4] After receiving a telegram from President Davis on September 5, 1864, in which Davis stated that “No other resources remain,” Hood determined to disengage from Sherman. “I hereupon decided to operate at the earliest moment possible in the rear of Sherman, as I became more and more convinced of our inability to successfully resist an advance of the Federal Army.” Please see “Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate States Armies,” by John Bell Hood, (New Orleans, 1880), pp. 245-246.

[5] “Shrouds of Glory: From Atlanta to Nashville: The Last Great Campaign of the Civil War” by Winston Groom, (New York, 1995), p.61.

[6] Please see “The Papers of Jefferson Davis,” Rice University, for the full text of Davis’s Macon speech. https://jeffersondavis.rice.edu/archives/documents/speech-macon-georgia [accessed January 1, 2018].

[7] “John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General” by Stephen M. Hood, (Savas Beatie, 2013), p.82.

[8] An August 25, 1875 letter to General Hood from General S. D. Lee, commanding a corps at Franklin, is instructive. The letter directly addresses the non-attack at Spring Hill and the actions of Generals Cheatham (commanding a corps), and Patrick Cleburne, a division commander in Cheatham’s Corps.

“I met A.P. Stewart at Columbus about 6 weeks ago and profounded, why was no battle delivered at Spring Hill? He replied in substance that Cheatham & Cleburne determined it was not best to bring on an engagement at night. He said he heard or believed that Cleburne regretted it immediately afterwards, and said no such weight should be on his mind for similar cause again & in that feeling lost his life at Franklin soon afterward. He further said he thought you were in a measure to blame as you were on the ground & could have put the troops up yourself or seen it done. As for himself he was put in position on the Columbia side of a creek to cut off any movement of enemy in that direction & was not moved from that position till near dark. He did not state the fact as to Cheatham & Cleburne on his own positive information, but said he believed such was the case & he had heard so.”

On September 10, 1877, W. W. Old, a Virginian on General Edward Johnson’s staff, wrote the following to General Hood.

“I met this morning, Mr. E. L. Martin, who was an aide-de-camp of Genl. Edward Johnson at Nashville… In regard to the attack at Spring Hill, Mr. Martin says that Genl. Johnson did go to Gen. Cheatham and beg him to let him attack with his division, stating he did not even require any support, but that Genl. Cheatham refused, stating finally he was opposed to night attacks. Mr. Martin says he was present.”

Further information on Spring Hill is available in Stephen M. Hood’s excellent study of General Hood’s military reputation, “John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General” (2013/Savas Beatie), as well as Eric Jacobson’s and Richard R. Rupp’s excellent book, “For Cause & For Country: A Study of the Affair at Spring Hill & the Battle of Franklin” (2007/O’More).

[9] “The Tennessee Campaign of 1864,” Stephen E. Woodworth and Charles D. Grear, editors, (Southern Illinois University Press, 2016), P.87.

[10] “Eyewitnesses at the Battle of Franklin” edited by David R. Logsdon, (Kettle Mills Press, 2000), p.16.

[11] S. A. Cunningham, “Reminiscences of the 41st Tennessee: The Civil War in the West,” John A. Simpson, editor, (White Mane Books, 2001), p.97 as quoted in “John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General” by Stephen M. Hood, (Savas Beatie, 2013), p.168.

[12] “Co. Aytch, Maury Grays, First Tennessee Regiment or A Side Show of the Big Show” by Samuel R Watkins, Times Printing Company, (Chattanooga, TN, 1900), P.209.

[13] Levi Tucker Scofield, “The Retreat from Pulaski to Nashville, Tenn, Battle of Franklin, Tennessee, November 30 1864,” (Cleveland, Ohio; 1909), p.39.

[14] “Memoirs of George Little,” (Tuscaloosa, 1924), p.59. “The morning after the battle, I personally superintended the collection of three thousand muskets that had been left on the battlefield by men who were either killed or so badly wounded that they could not carry their guns; the officer who had charge of the collection of guns on the other end of the line collected fully as many more. I put the muskets that I had gathered on the lower floor of a brick house and they were so heavy that they crushed through the floor. When General Cheatham came in and I reported the extent of our losses, he was so overcome with the thought of the death of so many good men that he burst into tears.”

[15] “The Battle of Franklin,” Philadelphia Press, Frank A. Burr and Talcott Williams, March 11, 1883, pp.7-28 as quoted in “For Cause and For Country: A Study of the Affair at Spring Hill and the Battle of Franklin,” by Eric Jacobson, and Richard R. Rupp, (O’More Publishing, 2008), pp.408-409

[16] Please see Civil War Trust, “Restoring a Battlefield;” https://www.civilwar.org/learn/articles/restoring-battlefield [accessed January 3, 2018].

[17] Levi Tucker Scofield, “The Retreat from Pulaski to Nashville, Tenn, Battle of Franklin, Tennessee, November 30 1864,” (Cleveland, Ohio; 1909), p.34.

[18] Wyeth, in his “Life of Lieutenant-General Nathan Bedford Forrest” (1908 ed., p.51) describes this comment as “one of Forrest’s maxims” but neglects to state if he originated it. Tanner in “Retreat to Victory?: Confederate Strategy Reconsidered” (2001, p.77) appears to suggest that the originator of the sentiment, but not the phrasing used by Forrest, was military theorist Von Clausewitz who wrote before the Civil War, “It would be futile—even wrong—to try to shut one’s eyes to what war really is from sheer distress at its brutality.”

[19] Please see Confederate Veteran, “About the Death of General Garnett,” S.A. Cunningham, editor, vol. 14, (Nashville, 1906), p.81.

[20] “Confederate Military History: A Library of Confederate States History, in Twelve Volumes Written by Distinguished Men of the South,” vol. 8, Clement Evans, editor, (Confederate Publishing Company, 1899), p.286.

[21] Ibid., p.286.

[22] Confederate Veteran, “Gen. John Adams at Franklin,” vol. 5, S. A. Cunningham, editor, (Nashville, 1897), p.302.

[23] “Battles and Sketches of the Army of Tennessee,” by Bromfield Lewis Ridley, (Mexico, Missouri, 1906), p.416,

[24] Please see “Historic Markers Across Tennessee”; http://www.lat34north.com/HistoricMarkersTN/MarkerDetail.cfm?KeyID=028-A15&MarkerTitle=General%20John%20Adams%2C%20CSA [accessed January 3, 2018]

[25] James Barr, undated Letter to the Editor in “Southern Bivouac: A Monthly Literary and Historical Magazine,” Basil W. Duke and R. W. Knott, Editors, Volume 1, June, 1885-May, 1886, (Louisville, 1886), p.315.

[26] Confederate Veteran, “The Battle of Franklin,” vol. 11, S. A. Cunningham, editor, (Nashville, 1910), pp.166-167, quoted in “The Gallant Dead: Union and Confederate Generals Killed in the Civil War,” by Derek Smith, (Stackpole, 2005), p.321.

[27] Confederate Veteran, “Gen. John Adams at Franklin,” vol. 5, S. A. Cunningham, editor, (Nashville, 1897), p.302.

[28] “Battles and Sketches of the Army of Tennessee,” by Bromfield Lewis Ridley, (Mexico, Missouri, 1906), p.419.

[29] Confederate soldier Byron Bowers of Ferguson’s Battery, Review Appeal, (Franklin, TN), February 24, 1972 quoted in “Eyewitnesses at the Battle of Franklin” edited by David R. Logsdon, (Kettle Mills Press, 2000), pp.83-84.

[30] “Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate States Armies,” by John Bell Hood, (New Orleans, 1880), pp.299-300.

[31] Please see “The McGavock Confederate Cemetery,” by Eric A. Jacobson, (Vaughan Printing, 2007).

[32] Please see “Battles and Sketches of the Army of Tennessee,” by Bromfield Lewis Ridley; Missouri Printing and Publishing, (Mexico, Missouri, 1906), pp.417-419.

[33] Ibid., p.420.

[34] Confederate Veteran, “National Park for Franklin,” vol. 18, S. A. Cunningham, editor, (Nashville, 1910), p.16.

[35] Please see The Tennessean, “Franklin to Consider Battlefield Park Funding Plan,” 3/26/2105; http://www.tennessean.com/story/news/local/williamson/2015/03/26/franklin-consider-battlefield-park-funding-plan/70523322/ [accessed January 3, 2018]; also, “Carter Cotton Gin Campaign,” Save the Franklin Battlefield, Inc.; http://www.franklin-stfb.org/cottongin_campaign.htm [accessed January 3, 2018].

[36] “Mrs. McGavock rendered every assistance possible and her name deserves to be handed down to future generations as that of a woman of lofty principle, exalted character and untiring devotion.” “Doctor Quintard, Chaplain CSA and Second Bishop of Tennessee: Being His Story of the War (1861-1865),” (The University Press of Sewanee Tennessee, 1905), pp. 113-4.

[37] Please see Confederate Veteran, “The Good Samaritan at Franklin,” vol. 30, S.A. Cunningham, editor, (Nashville, 1922), p.448.

[38] Please see City of Franklin, Tennessee; “Eastern Flank Battlefield Park;” http://www.franklintn.gov/government/parks/facilities-and-parks/park-locations-maps/park-locations/eastern-flank-battle-park [accessed January 4, 2018].

__________________________________

Daniel Mallock is a historian of the Founding generation and of the Civil War and is the author of Agony and Eloquence: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and a World of Revolution. He is a Contributing Editor at New English Review.

More by Daniel Mallock.

Help support New English Review.