Can We Make Education More Likeable?

by Christopher Ormell (May 2023)

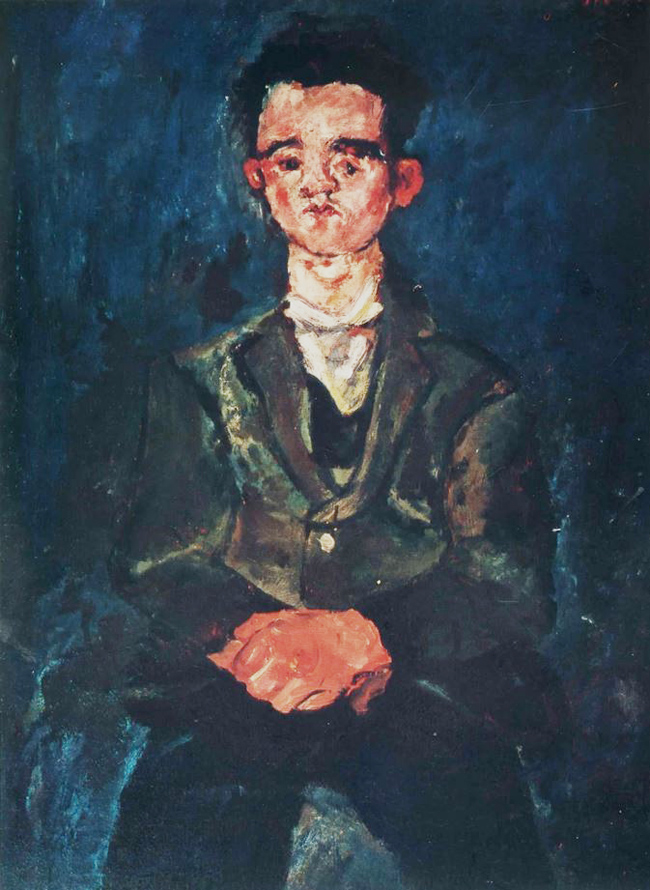

Boy in Blue, Chaim Soutine, 1928

When Neil Postman published his book The End of Education in 1995 it was well received by the critics, who mostly praised its compelling, though necessarily downbeat, theme. But qualified praise was not, really, an appropriate response. Postman’s book should have been hailed as a ‘moment of truth’ or even more appropriately, as a ‘moment of alarm’. No civilisation can grow and prosper without effective education, which is essentially the transmission to youth of the central core and essence of the enduring classless culture of the society. Without this vital transmission, it will, inevitably, begin to falter. Today’s civilisation is particularly dependent on good education, because our way-of-life nowadays is based on knowledge, imagination and insights twenty times more sophisticated, abstract and difficult than those on which our great grandfathers and grandmothers relied a hundred years ago.

So have we taken the trouble to ensure that the methods we use in schools—to ‘get through to’ youngsters—are twenty times more powerful than those which were typically being practised in the 1920s? Such a question can only be a joke. It is doubtful whether the teaching methods being used in schools today are ‘getting through to’ current youngsters half as well as those of that now distant era.

Which raises the multi-headied question, “Why?” Why have we been unconsciously sleepwalking for decades, operating a substandard schooling scheme which is palpably failing children, parents, teachers, heads, science, technology, business …? It is a scheme devised and run by so-called ‘cognitive scientists’, who, we know, treat the human brain as if it were a computer, and assume that children learn things in school much as cameras turn the photons which hit their receptors into permanent images. But children are much more complicated than this, and their minds are much, much more selective. Their thoughts are often in dreamland or coloured with tension and emotion. Some of today’s children are also quite sceptical about adult points of view. There is a ‘Thunberg effect’ which is a belief of some of the most mentally active children that some of today’s adult wisdoms are pathetically unsafe.

‘Cognitive science’ is the current name of a body of thinking—which dominates educational systems around the world—which used to be called ‘behaviourism’ and which flatly denied that human beings had minds. (Today they claim to have changed their minds, but they still don’t get it. They now say the word ‘mind’ refers to an obscure neural register in the human brain!) According to these determined positivists, mindtalk was hot air: a fallacious rhetoric lacking any verifiable basis. What really mattered, they argued, was the effect of talk on a person’s subsequent behaviour (=what they said and did). In effect they were rubbishing the humanities, including literature, history, poetry, art, music, mainstream psychology, philosophy, mysticism and all forms of religious belief.

Of course they knew, perfectly well, that they had their own private thoughts, attitudes, moods, feelings, pains, etc. but they willfully tried to banish such items from being mentioned in public.

Their bible was Bloom’s Taxonomy, a product of the 1950s when positivism was still regarded as a viable, respectable point of view. It laid out the kinds of ‘behaviour’ (saying, writing, drawing, colouring, working gadgets, symbol-manipulating …) which, they imagined, teachers (‘instructors’) ought to try to inculcate in their pupils. These were plain, neutral, functional routines which the students were supposed to be drilled (instructed) into carrying out—in a plain, neutral, functional way. It was definitely not a recipe to make the child’s school experience likeable.

Elsewhere many sensible lay people were, at the time, adamant that schooling should be all about ‘building character’ … which would show up, of course, in ‘good’ (=reliable) behaviour. But this commonsense, praiseworthy emphasis on ‘good behaviour’ was miles away from what the behaviorists called ‘behaviour’. The behaviourists had, in effect, coined a new variant of the word ‘behaviour’ to suit their blinkered view of human nature. It was another dangerous ambiguity, one which became embedded in education … one potentially going to mislead any hasty thinker. ‘Behaviour’ meant quite different things to those who felt that schools should concentrate on building character, and those who thought it was all about training youngsters to carry out neutral, valuefree routines.

Of course schools do have to train their pupils in the routines mentioned above, but to suppose that this is all that schools should do is to suppose that schools should be value-neutral, brain-washing institutions, and that ‘education’ based on feeling and values is not part of their remit.

In effect they were also coining a variant of the word ‘education’, to denote drilling students on valuefree routines.

So what is the original, genuine meaning of the word ‘education’? It can be spelled out like this: feeding the mind of youth, sharpening their appreciation of a 1001 different worthwhile human preoccupations, creating a love of understanding, increasing their curiosity, energising their problem-solving powers and building authentic, deeply internalised, confidence. These are the forms of cognitive joy which have been—in effect—rubbished by the behaviouristic managers who hi-jacked education more than thirty years ago. Without these rewards, it is more difficult to get children to acquire routines. When no attempt is made to ‘educate’ in the time-honoured sense of the word, schooling becomes a grey, thankless, chore—both for pupils and teachers.

So the politicians who let these brash ‘cognitive scientists’ take over schooling—which is what happened in the UK in the 1980s—were responsible for a blunder of the first magnitude. Unfortunately the behaviourists they mistakenly empowered have since passed themselves off as computerologists and sold their simplistic notion of the human mind to upstart research institutes, which have developed so-called ‘knowledge engineering laboratories’ … brazenly ignoring the fact that philosophers of genius have been probing the nature of knowledge for more than two millennia and have found that it is full of strange, unobvious contradictions and bottomless pits of incoherence.

Of course we need research institutes to explore how to get computers to recognise handwriting, the spoken word, common objects, etc., but calling this activity ‘knowledge engineering’ is another word-coining ploy which can become a fresh source of confusion.

Today our total heritage of knowledge is the fruit of millions of hours of the hardest of hard thinking, conceptualising and research, not to mention the sacrifices of brilliant, determined, brave pioneers like Archimedes, Galileo, Bruno, Mendel and Madame Curie. It would be a howling category mistake to think that ‘knowledge’ (a high status achievement term) can be lightly messed about by a process described as ‘engineering’ —a term which emerged from metal working. What its experts call ‘knowledge engineering’ would be more accurately described as ‘digital electronic and software development’.

The blunder of the 1980s—which handed schools over to ‘cognitive scientists’ —was comparable to that which had been made twenty years earlier (in the 1960s) when schools were told by the Eisenhower government to switch their maths lessons “away from numbers” and treat them instead as “the study of sets”. (The government had been talked into this dubious move by distinguished but myopic mathematicians.) Fortunately the earlier blunder was quickly reversed, but such is the total mesmeric power of IT and computers, that nearly half a century has passed, and the second blunder is still disgracefully in place… virtually unchallenged. The classroom regimes it promotes may be characterised as operating ‘factory schooling’, because they result from a seriously misguided scheme to get students—supposedly ‘efficiently’ —to rote-memorise information and process.

That this factory approach is not the best way to ‘get through to students’ is obvious to anyone who has experienced trying to teach unwilling classes. But it seems that those who determine the shape of schooling are blinded by an overweening and virtually unshakeable computer mindset. The ideologues haven’t personally encountered this dumb resistance, and they don’t take any notice of those who have. They think they know better. And whether we like it or not, their say-so has become ‘the official line’ —the nod which allows schools to continue to operate on ‘cognitive science’ lines, and to treat this misguided approach as if it were an unquestioned ‘scientific truth’.

In effect the switch of school systems to ‘cognitive science’ came about around 1980, because an earlier ideological academic obsession with sets in mathematics had created havoc in education. Education systems are normally inherently conservative … for the very good reason that the signs that a radically new approach in schools is flourishing—and repaying the huge effort to establish it—these take about thirty years to consolidate. What teachers teach is mental preparation for their pupils, i.e. preparing them by introducing them to outline concepts needed in challenging adult situations … ones which will only materialise for the average individual 20 or 30 years later. But, this is happening in societies where the cognitive and cultural tenacity of corporate business, politics and social mood is frankly short and shaky. It is often said that a week is a long time in politics. In business some short time horizons are equally common, e.g. the end of the next financial year. Social mood is always, of course, intrinsically fickle, and social media has brought even shorter horizons than we had before. So the long-timescale-thinking which is necessary—if we are going to be fully sure that a new mode of education is working well—this is dangerously missing.

It was, alas, dangerously missing in 1980.

When the mandarins in Westminster decided to let cognitive scientists take over education, they were reacting to an urgent, crisis situation created by the chaos of ‘new maths for schools’ and ‘progressivism’ twenty years earlier. They were taking a massive leap into the unknown. Yes, the ‘cognitive scientists’ who were knocking on the door were full of confidence, but this was not based on the slightest previous experience of running schools. It is unclear to what degree the mandarins of 1980 were aware that they were taking an enormous gamble.

It has turned out to be a dreadful mistake. These ‘cognitive scientists’ who still run the school systems don’t understand human nature—by the time-honoured standards set by the humanities. Most of them have had virtually no exposure to the humanities. They are not good judges of meaning. They have failed to respond to a chorus of complaints from business for forty years—that many school-leavers lack work ethic, standard skills and even basic social competencies. By almost every social parameter (amounts of drug abuse, violent crime, mental distress, failed relationships, aberrations in the police, burnout by nurses and doctors, truancy … ) things are going downhill. This is just what one would expect from a school approach which is badly, deeply, sickeningly, flawed.

So is this truth widely recognised? Not in the corridors of power.

This is probably because there has been no significant, mass outcry against cognitive science. It is also apparently protected from serious criticism as a result of its closeness to computer theory … and behind that, by the tacit ideology that computers can do no wrong. There are many teachers who have doubts about ‘cognitive science,’ but their position in the public pecking order is far too weak to dent the overweening confidence of the ideologues. It is ironic to the nth degree that the low position of teachers in the pecking order—resulting from the public’s disillusioned view of the efficacy of today’s schooling—is effectively the main factor which is holding this whole sorry, dysfunctional mess in place.

Thankfully there are some exceptions to this dismal verdict: some private schools, some schools run by perceptive, personable heads, some classes taught by perceptive, dedicated teachers, some parents who step-in to compensate for their local school’s shortfalls, some self-aware children who instinctively know the difference between swallowing facts and understanding them. But there are, alas, also millions of children and thousands of schools which are stuck in a barren rut… emphasising and re-emphasising the obsessive mantra Learn! Learn! Learn! They are trying ever so hard to make the ‘cognitive science’ factory formula work—by increasing the pressure on students. But it is a pressure which only makes matters worse.

A lot of ‘waking up’ is going to be needed. Silicon Valley itself is aware that the education system is in crisis, because they are finding it more and more difficult to recruit mathematically well-educated young programmers. Their solution: to use AI and in particular chatGPT to teach math. But if young minds are being put off math by flesh-and-blood human teachers (as they evidently are), it is difficult to see them warming to cold motivational rhetoric synthesised out of nothing (neural networks) and lacking even a fig-leaf of human authenticity.

The arrival and amazing development of computers is of course the great event of the last hundred years, but it has happened at a time when formerly dominant, much-treasured cultural and moral standards were falling into serious decline. So it is understandable that most people greatly admire and envalue the fresh perspectives which computers are bringing to our engagement with today’s damaged world. (Palpable progress is being made, at a time when quite a lot of other things are going downhill.) But there is an ever-present danger that this computer monopoly of hopes-for-the-future will go over the top. Too much emphasis on ‘efficiency’, ‘structure’ and ‘order’ (not to mention the familiar exaggerations and hype which have fuelled the computer sector for sixty years) can easily morph into human oppression. In the case of so-called ‘cognitive science’ it is subjecting millions of children to pressured learning. They are under the hammer of a heavy imperative—to memorise information … presto. This is experienced by many children as brutal imposition, or if you prefer, bullying. And as forced feeding is the worst possible way to get reluctant eaters to consume unfamiliar food (which may actually be delicious cuisine), so forced learning is the worst possible way to get reluctant learners to take an interest-in, and to enjoy, what looks to them like alien, unfamiliar, dull stuff (but which actually can lead to genuine cognitive satisfaction).

It is probably mainly the sense that children have of being imposed on, which ruins memorisation as a teaching approach: a fact which teachers trapped in strict managerial regimes sometimes try to alleviate by telling their classes to take it or leave it—i.e. posting it as their choice whether they want to get the ‘good grades’ which parrot learning will or may deliver … a potential meal ticket for the future. If they do, then—the teacher is saying—the way to get that result is to do the work. But such alleviation is not popular in the corridors of power, because in many schools only a minority of students choose to do the unsatisfying work.

It can be argued that attempting to force children to learn large chunks of dreary, valuefree, nondescript information should be re-classified as ‘child abuse’. What a young person voluntarily learns is, for them, a very personal thing. When they learn it (take it fully into their personal picture of the world), they do this because they recognise the value of it. By contrast, when they are pressured into memorising bland, unsatisfying stuff, it rarely lasts for very long. So this can’t be classified as ‘education’. To count as ‘genuine education’ it must be capable of lasting a lifetime.

So the $64 question is: how to get children in schools to value a curriculum which consists of hundreds of items—which have been carefully selected by a committee of distant experts as ‘what they chiefly need to know’ —and which often look initially—to the child—like ‘dull, valuefree, uninteresting information’?

A school which consistently offers unattractive information, like a restaurant which only offers unappetising food, is going to fail … by genuine educational yardsticks.

So schools have got to ‘warm up’ and become friendlier places for students. But of course their first priority and their raison d’etre is to educate the students. This won’t happen if they treat friendliness per se as the main requirement—this was the fallacy of progressivism. Many idealistic young teachers became deeply convinced in the 1960s that schooling ‘must get away from the threadbare pedagogy of the past, and become child-centred’. But by making this the main objective, they tended to let children choose undemanding options, and follow trails previously implanted in their minds by media, ads, and pop culture. Some radical teachers who believed in the divine right of teachers to teach their own opinions got their classes mentally activated by positively radicalising them against the society … their own society. (This could hardly be worse as an outcome, because schools are fundamentally tasked to transmit the regular, uncontroversial wisdom of the society to youth.)

Progressivism involved turning a blind eye to the fact that the children were not being mentally well-prepared for an extremely demanding modern reality. It was a cruel con, because it gave the children a false picture of their future, one which gave them the impression that everything was going to be easy, that mental laziness was OK, and which carried no hint that they would soon be pitchforked into an unforgiving, unpaternalistic adult world.

So the kind of ‘friendliness’ schools need to show is an intrinsic, cognitive friendliness drawn out of the nature of the curriculum itself. This means that the curriculum must make a lot of sense to the child. It should enrich the child’s vision of the world. It should all hang-together as a coherent whole, and thereby give a lot of cognitive satisfaction (sometimes called ‘intellectual eros’). The curriculum should be experienced by the child as a colourful, dramatic, exciting narrative.

All of which can sound unrealistic, given the serious dearth of this kind of ‘sweetness and light’ circulating in today’s disoriented, discontented adult world. But there is no established principle which says that that schools must scrupulously mirror the down-at-heel attitudes, pessimism, cynicism and nihilism of the current adult scene. It is a great mistake to think that the so-called ‘Good Old Days’ were free from negative feelings. On the contrary, every decade from the 1920s to the present day was widely experienced at the time as an uphill struggle against wars, poverty, violence, exploitation, injustice, brutality, depression, etc. At the time the minority of good schools—and there were probably more of them then than we have today—were generally regarded as places where much youthful pride, positivity and idealism ruled OK. In other words, it was accepted as a normal state of affairs that schools were going to be more coherently (youthfully) socially organised than the competitive, often chaotic, sometimes catastrophic, workplace and marketplace. The schools had some distinctly coherent positive narratives to convey to their students … ones which took it for granted that there was a ‘moral order’, that mathematics was a treasure trove of provable certainties, and that ‘the pursuit of truth’ was the supreme, the especially important, moral value.

A concerted effort needs to be made to bring about a similar moral gap between the culture of schools and the culture of today’s disillusioned adult society. The notion that schools ‘must reflect the ‘anything goes, non-judgmental society’ because society is non-judgmental and multicultural, needs to be contested. It (the downbeat assumption) subtly acts as a negative leveller—a let-down which implies that schools should force students to accept bland, drab, colourless discourse, inevitably suggesting a bland, drab, colourless future. We should try to arrive at local state of affairs where there is a range of diverse community schools each operating with its own different stable, ethnic, moral and cultural favoured modes but nevertheless committed to the commongood. (To paraphrase Sinatra, each school should be able proudly to sing We did it our way!) Each school should adopt its own distinctive moral line—while fully acknowledging the overall authority of the secular state. They should treat their line as ‘the norm which counts’ within their walls. Parents and children, when deciding which school the child should enroll at, should be fully aware of the cultural emphases on which each school is operating. Let’s remember that immigrants, who arrive from distant countries normally manage to do so only after mustering great implicit courage. They also tend to be admirers of the relatively free anglophone culture they want to join. They certainly didn’t go to all the trouble, strain and upset of migrating… in order to muddify, neutralise or debilitate the culture of their new, chosen homeland. In most cases they will, of course, naturally wish to retain a fond memory of their former culture, but not as something which over-rides, resists or contradicts the new.)

Education is not a word which betokens the transmission of grey, objective, nondescript ‘information’ … like tapwater being pumped into homes. This kind of ‘transmission’ will soon be forgotten. Any transmission worthy of the name must be capable of lasting a lifetime. It will have to be much more memorable … a transmission of interest, solidarity, loyalty, fascination, insights, understanding, agendas-for-promising-futures, justice, creativity. Schools need to be places which are alive with joie de vivre, places whose central purpose is to grow the mental energy, articulacy and integrity of their students.

But … this won’t be accomplished easily. The only way to bring-to-life the official curriculum which has been blandly summarised by a distant committee of VIPs, is for the teacher to bring a lot of student-friendly imagination to bear on it. And the main form such energising imagination must take arises from asking the question: What would it have been like to be there?

This is the gist of the philosopher R. G. Collingwood’s method of getting to understand the past. It involves carefully de-centering into the tensions, risks and awkwardnesses which confronted people stuck in difficult environments long ago.

Yes, when Napoleon escaped from the island of Elba he soon gathered a rag-tag following of supporters intent on trooping up the Rhone valley towards the North. How did Napoleon think such an unruly, unpaid rabble could take-on the full might of the French state? How did anyone who joined that motley crowd think they could triumph? Well, destiny played into their hands, because the Bourbon government in Paris sent Marshall Ney with a well-equipped army to stop Napoleon in his tracks. They forgot that Napoleon and Ney had been old friends, and that the Marshall would, after agonising deliberations, throw his lot in with Napoleon, rather than his Parisian taskmasters.

So the magic formula which can make boring information memorable, is vividly imagined de-centering. This often means asking the question What would it have been like to be that person? And the size of the challenge we face today is to find a cadre of imaginative teachers who can do this—skilfully and effectively—in an age which has, alas, to all intents and purposes, sadly turned its back on imagination. This rejection is the bad news. For a very long time ‘Imagination’ has had a poor press. The exercise of imagination is nowadays treated as the commonest cause of silly failure. (He made that blunder because he imagined XYZ. It is assumed that anything a person has ‘imagined’ is almost certainly wrong.) Of course spectacular successful public feats of imagination are still widely admired, but they are treated as ‘exceptions which prove the rule’.

How has this happened? Well, imagination is a quest for how things might be as opposed to how they are. The overriding tendency behind today’s dominant de facto culture is getting a secure grip on how things are, not messing about with what they might be. As a side-effect, today’s supposedly ‘efficient’ factory-type schooling has almost extinguished any trace of imaginative sensibility in classrooms. Huge industries have grown up during the last sixty years (sci-fi, computer games, fantasy fiction, metaverse …) which now deliver ready-made glossy image-streams of ‘might-be reality’ —thus strongly suggesting that there is no longer any need for anyone (except stars) to do personal ‘imagining’.

But we all need realistic imagining (‘envisioning’) to plan our day, not to mention the coming year and our subsequent life path.

And this relative absence of personal imagining in everyday life is probably the worst possible state-of-affairs in a rapidly changing society, because trustworthy imagination in society is the vital factor needed to initiate and sustain innovation, progress and reform. If widespread social chaos is to be avoided, everyone in society needs to feel that the future is going to be better than the past: so innovation, progress and reform are not luxury items. They are, rather, essential life-lines … ones urgently needed to maintain standards and keep the wheels of the economy turning. Every business needs a positive narrative: a worthwhile, grounded vision of what they are going to be doing in the next five years.

Otherwise, left virtually untrained and under-practised, imagination tends to become sour, wild, and erratic. This is not the answer. We are seriously under-nourishing the royal jelly (disciplined imagination) required in small helpings to make life bearable, and in large helpings to make it exciting. In a fast-moving society a capacity to envisage future possibilities before they happen is essential—simply to cope with ordinary life. Somehow we have got to find a way to build copious imagination, envisioning and de-centering back into the modus vivendi of schools.

The author is an older philosopher, now aged 93, who has been leading campaigns radically to renew education generally since 1993 (via the PER Group), and radically to renew mathematics education since 1969 (by promoting the Peircean interpretation of mathematics).

Table of Contents

Christopher Ormell is a philosopher who has combined linguistic analysis with targeted conceptual synthesis during a long career. He was co-founder (with the late Eric Blaire) of the Philosophy for Educational Renewal (PER) Group in London in 1993.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast