Canadian Magical Mystery Tour

by Geoffrey Clarfield (May 2023)

Indian Rug, Paul McCartney, 1994

It was just another day in the life. I woke up, got out of bed, had some coffee and checked my email. The first message read, “Dear Geoffrey, are you the person who wrote an article about George Harrison’s sitar teacher Shambhu Das in the National Post, November 15, 2010?” I answered, “Yes I am, how can I be of help?”

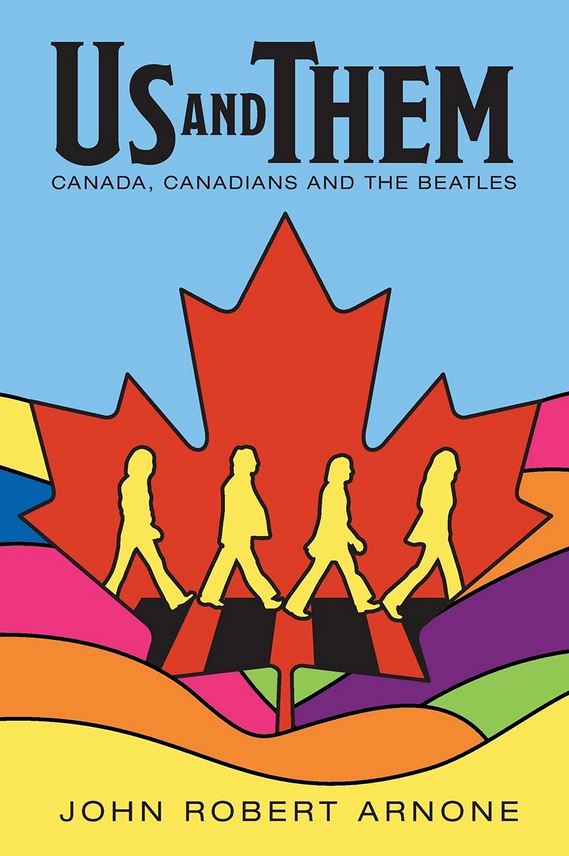

Soon after, I was on the phone talking with Torontonian, John Robert Arnone, a fellow Beatlemaniac, who is also a serious Beatles researcher and published author. John is already hard at work on the second edition of his revealing and insightful study, Us and Them, Canada, Canadians and the Beatles, a book that chronicles the influence the Beatles have had on Canada and Canadians, and more subtly, the relatively disproportionate influence that Canada and Canadian culture has had on the Beatles.

Soon after, I was on the phone talking with Torontonian, John Robert Arnone, a fellow Beatlemaniac, who is also a serious Beatles researcher and published author. John is already hard at work on the second edition of his revealing and insightful study, Us and Them, Canada, Canadians and the Beatles, a book that chronicles the influence the Beatles have had on Canada and Canadians, and more subtly, the relatively disproportionate influence that Canada and Canadian culture has had on the Beatles.

John wanted to know more about Shambhu, what he had told me about George Harrison and what he was like as a teacher. I had interviewed Shambhu before he passed away and used only some of the material for my article in the Post.

I emphasized Shambhu’s devotion to Hinduism, his discipline, musicality, dedication to his students, his natural humility and good nature, how he tutored George and became his friend, and his incredible and largely unrecognized (apart from a small group of students) musical talent. For example, not only did Shambhu organize the Indian musicians who played on Harrison’s Wonderwall film soundtrack album, but a minute or two of his inspired sitar playing can also be heard on that same album.

Within a day or two, John had his draft piece on Shambhu for the next edition ready for me to read and which included some of the things I had told him. I then went online, ordered John’s book and binge read it during a relaxing winter holiday in sunny Florida. I discovered much.

The book gave me perspective. It helped me better come to terms with the profound and long-lasting effect that Beatles songs have had in my life. I could now compare some of that with many other Canadians my age, post war baby boomers as reported by younger writers such as John, who had experienced Beatlemania in Canada, not in the UK, Europe or America.

I discovered that Paul McCartney’s first public performance was a partial function of post war holiday camps created by an employee of the Eaton family of Toronto and Canadian Armed Forces veteran who, after WWI returned to the United Kingdom. I also found out that the producer who finally hired McCartney at the height of his career to write the “Live and Let Die” theme song for the James Bond film of that name was also one of these transplanted, trans-Atlantic Canadian entrepreneurs based in the UK.

I read that George had once considered immigrating to Canada, that he had family in Ontario and Quebec and that George’s mother bought him his first pair of leather “Beatle boots” here, which the other fab four imitated and that contributed to their signature look.

I can remember, as if it was yesterday, (no humor intended) buying my first pair of ‘Beatle boots’ on Eglinton Avenue in imitation of the Beatles. I also discovered that like millions of other Canadian kids, because of the close and collegial relationship between Capitol Records, Canada, and the UK, we got the first Beatles singles and the first album before they broke in the United States.

I may have passed Arnone on my bicycle, as he shined shoes and swept floors at his dad’s barber shop in the sixties, near Eglinton and Avenue Road, across the road from the Eglinton Theater where I probably saw the film Yellow Submarine, way back when. I clearly remember walking down Eglinton Avenue one sunny day in my boots, listening to “She Loves You” on Chum Radio (on my hand-held transistor radio) months before the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan, which of course sitting in front of our black and white TV beside my brother and sister, I did not miss.

The Beatles gave nine performances in Canada during their various North American tours. When they were still touring here they thrice played in Toronto. Somehow, I missed those concerts and regret the fact to this day. I did hear about them on radio and TV and found their interviews hilarious.

These exchanges with the media reminded me of the British comic actor Peter Sellers whom I later discovered was one of their role models and friend. You can see him briefly visiting them in the studio in Peter Jackson’s recent documentary on the making of the Beatles album “Let it Be,” called “Get Back.”

If you jump to the end of Arnone’s book you can read a series of short vignettes about famous Canadian musicians and how the Beatles influenced hem. My favorite and most surprising tale is that of Joni Mitchell, who as she built her career as a folk singer ,would sing Beatles songs in clubs before she decided to concentrate exclusively on her own material. In the same vein, it is hard not to mention that Celine Dion’s late husband used to sing translations of Beatles songs in French in his own band in Quebec.

Neil Young and Robbie Robertson of the Band are big Beatles fans and John was hosted in Mississauga by Robbie’s mentor Ronnie Hawkins during one of his trips here. I am sure that Arnone could fill an entire book with interviews of how Canadian musicians have been influenced by the Beatles.

The most curious tale in the book is about a London based dentist. As the Beatles career took off, it was clear that their look was almost as important as their sound, and until then dental care in post war England for the sons and daughters of the working classes, was almost nonexistent.

Beatles like George (and Paul and no doubt the others) needed dental work. George had found an upper class, upscale dentist to work on his teeth. The dentist recognized that the Beatles were the up and coming thing and invited George, John and their better halves to dinner one evening.

At the end of the meal his girlfriend and future wife, a young woman from Hamilton Ontario, spiked their coffee with LSD. That trip has been written up by many writers and in some detail by Mark Lewisohn in his first book of a biographical trilogy on the Beatles.

The thing is, that it is most likely that this simultaneous psychedelic experience opened up a level of creativity among John, Paul, George and Ringo that brought us the surrealism of Revolver, the magic realism of Sergeant Pepper and the Beatles trip to India to study transcendental meditation with the Maharishi Mahesh Yoga.

Arnone plausibly argues that the name Sergeant Pepper may have actually been inspired by an OPP police officer of that same name who took care of the Beatles during their 1966 Toronto gig and whose easy, familiar Canadian style won over the Beatles who were often wary of police and authority, both in the UK and the States. Paul even wore an OPP patch for the inside cover photo of the album.

In George’s case his engagement with Indian culture and music led him to an eventual adoption of the worship of Krishna which changed his life, his music and amplified an already growing interest in the culture and spiritual offerings of India and the East to baby boomers looking for metaphysical alternatives to the Judeo-Christian tradition.

And so many of the songs from the White Album were composed at Rishi Kesh in the foothills of the Indian Himalayas where a young Canadian named Paul Saltzman was allowed to “hang out” with the Beatles in their closed compound and take as many photos of them as he wanted. His book and the film about his experience with The Beatles has been a best seller for some time. And the book reveals a Saskatchewan sax player and Ontario violinist were hired to play on the White Album!

For the record, there is also mention of a Vancouver impresario who let John, and then John, Paul, and George slip from his fingers while conducting BBC talent competitions in England in the late 1950s.

As to Canada’s influence on the Beatles here is just one example about an Alberta Cree woman who caught Lennon’s attention while protesting the living conditions of Indigenous people in Edmonton. He got her on the telephone and she recited a prayer her grandmother taught her. The theme was centered on the word Imagine. Lennon asked if he could use it, and months later wrote his signature song.

It goes without saying that when John and Yoko chose to create their peace campaign, they did so from a bedroom in a posh hotel in Montreal. Young Canadian film maker Josh Raskin did an Oscar-nominated documentary on another Canadian, Jerry Levitan meeting John and Yoko in Toronto, before the famous couple set off for Montreal. And, it was a French Canadian producer who made their bedroom recording of “Give Peace a Chance” for broadcast and sale. He earned a whopping 2,500 dollars for the job as it was paid according to music union rates. Speaking of union rates, Arnone also reveals Lennon was handed a paltry $265 to perform at Varsity Arena in 1969.

If you are a boomer like me, while reading Arnone, you will no doubt ask yourself, “Where was I when this Beatles song or album came out, what was happening to the Beatles at that time, what was I doing, what was I thinking (and feeling) and how did it affect me?” I know I did.

Now I can say with greater certainty that apart from penetrating my soul with some of the best songs of the 20th century, the Beatles journey also helped me to understand what it was and is to become an adult.

Their journey from girl crazy rockers, to men who discovered that love often means a serious, long term commitment to a person or idea, and that below the surface of our network of human relations there may exist an ever deeper, more mysterious inner voice that is both within and without you.

Their songs, although they cannot take us there, may point us in the direction of this inner light. If that is so, Arnone’s book can also serve as a handbook for this journey as he reminds us of Canadians largely untold and little-known role in the Beatles’ story.

Table of Contents

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast