by David Solway (January 2021)

The Jack Pine, Tom Thomson, 1916

Unstable dream, according to the place,

Be steadfast once or else at least be true

—Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542)

Poets were once known for being critics of the reigning cultural paradigms of their day. One thinks of major poetic figures throughout the ages—Archilocus, Horace, Juvenal, Dante, Milton, Dryden, Pope, Byron, Arnold, Yeats, Eliot, Auden and our own Irving Layton, among a prestigious roster. Fiercely independent minds and judges of the prevailing temper, many, at least for a time, were considered outriders, eccentrics and mavericks, and occasionally ostracized. Recording their insights and critiques in memorable verse, they did not hesitate to skewer the clichés and political assumptions embraced by their fellow citizens.

The same cannot be said for the poets of the current Canadian milieu. Our acclaimed versifiers are almost to a man and a woman affiliates of the norms and trends of the social landscape. They no longer challenge the fashions and superstitions of the day, but defer to them. Our poetic culture has for the most part descended into the politically correct dementia of our historical moment. Like the politicians, journalists and academics who have rejected reason and common sense, they support the feminist agenda, affect the notion of gender fluidity and pronominal promiscuity, believe in global warming or “climate change,” and of course have gone headlong Green, lobbying for renewable energy and the abolition of the oil and gas industry. Few Canadians are aware that Canada’s poetry community has jumped aboard the climate train to nowhere. Having enlisted in the ideology of Green, these poets place polemical advocacy and formulaic address above fidelity to craft and informed conscience.

Of course, ecopoetry, a thriving genre lazily piggybacking on current fashion, is not exclusively Canadian. Its most influential source stems from the theories of Norwegian philosopher and founder of the Deep Ecology movement Arne Naess, whose words, “the equal right to live and blossom” alluding to the interconnectedness of all organisms, could serve as the rallying cry for the school of contemporary redemptionist poets. The sentiment has gone viral, ramifying across the Western poetic canon.

One thinks of the much-lionized (if somewhat overrated) Australian poet Les Murray, who in his New Selected Poems praises nature and even the body as “know[ing] the meaning of existence,” but derogates “the ignorant freedom/of my talking mind”—an antihumanistic utterance candied over by the pretension of pastoral virtue. Notable American poet Hayden Carruth confided, “I consider myself and I consider the whole human race fundamentally alien. By evolving into a state of self-consciousness, we have separated ourselves from the other animals and the plants and from the very earth itself, from the whole universe.” The fact that only the “alien” has the capacity to write poetry or to engage in such preposterous self-loathing does not give him pause.

Then there is Robert Hass, former U.S. Poet Laureate and self-proclaimed environmental activist, whose Time and Materials is chockful of textbook ecopoetry, prompting The New Criterion poetry critic William Logan to respond, “By the time he’s done preaching about the destruction of the ozone layer” [and] “droning on about chlorofluorocarbons, you’re counting the tiles on the floor.” Fellow American Sam Hamill in his poem “Mythologos” from Habitation apologizes fulsomely to earth-goddess Gaia, asking her to “be benevolent/if you can; forgive us,” and then proceeds to “beg for mercy” in the name of those who are “plunderers in the temple” and “the dinosaurs of our age.” But there is one appropriate line in the poem—“Reason perishes with the habitat of its days”—of which the poem itself and the mindset it expresses are prime illustrations.

Canada for its part has become an Arcadian haven of versifying redeemers. Some of our best-known poets, like Dionne Brand, Michael Ondaatje and George Elliott Clarke, are signatories to an ecological movement known as The Leap Manifesto: A Call for a Canada Based on Caring for the Earth and One Another—shades of Mao’s Great Leap Forward. According to its mission statement “the manifesto aims to gather tens of thousands of signatures and build pressure on the next federal government to transition Canada off fossil fuels while also making it a more livable, fair and just society.” The primary victim of their agenda is the suffering province of Alberta, whose essential energy sector has been targeted for destruction.

Among the farrago of transformative recommendations made without a thought to their real-world consequences, the Manifesto focusses on investing “in the low-carbon social programs and infrastructure we need.” “Leaping into a new carbon-free economy,” they believe that “science is demanding that we get serious about the climate,” without understanding what serious, non-partisan science is actually telling us: Look before you leap. The science is not “settled” and the reliable data and indicators collected by thousands of reputable scientists and authors strongly point to the fact that climate alarmists and those invested in the global boondoggle have set us on a wrong and deviant track.

As far back as May, 2008 the Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine inaugurated a “petition project” containing the names of over 31,000 scientists who rejected the United Nations’ IPCC predictions about rising temperatures and carbon apocalypse. Indeed, leading scientists including Nobel Laureates have cast doubt on what they call “an implausible conjecture backed by false evidence” to form a damaging consensus and “a record of unfathomable silliness.” The eventual result will be, writes Richard Lindzen, Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Atmospheric Science at MIT, “a landscape degraded by rusting wind farms and decaying solar panels.” But our poetic elite pay no heed to the vast store of countervailing evidence regarding so-called “climate change.”

George Elliott Clarke, for example, who campaigned for Canada’s socialist party (the NDP), a former Parliamentary Poet Laureate and currently among Canada’s most celebrated poets, is a proponent of everything Green. His pastoral meditations in praise of an unsullied environment and of environment-conscience poets bespeak his passion for bucolic purity. Clarke’s over-the-top rhetorical fulmination in his closing speech at the inaugural reading of the Manifesto, calling for social justice and climate action, was nothing if not embarrassing, making up in decibels what it lacked in sobriety. It furnishes an instance of stentorian rhodomontade founded on the analytical vacuity typical of the movement. Furious self-assertion is no substitute for understanding.

What is known as wilderness poetry, or ecopoetry, is also big. Canada boasts a slew of locally respected ecopoets, including Tim Lilburn, the late Don Domanski, Anne Campbell, Dennis Lee, Jan Swicky, John Steffler, Fred Wah, and many others. Its most famous practitioner and maestro of the genre, the award-winning Don McKay, has authored more than a dozen books celebrating the union of soul and soil. It’s worth spending some time reviewing his oeuvre since his influence on the CanLit poetry scene has been pervasive.

McKay focuses on spirit of place, the natural landscape and a kind of geological ethics that condemns a “land…made plain/reasoned, and made smooth with use,” as he writes in “Scrub” from Birding, or desire. In “Song for the Song of the Varied Thrush” from Apparatus, we are urged to “realize the wilderness/between one breath/and another.” Wilderness, apparently, is a pulmonary aid for thought. This principle is evident in fellow practitioners like Wah, who is particularly breath-cathectic, reducing language to its respiratory components. Among Wah’s signature lines from Breathin’ My Name with a Sigh, we find:

Mmmmmmm

hm

mmmmmmm

hm

yuhh Yeh Yeh

thuh moon

huh wu wu

nguh nguh nguh

w_______h

w_______h

Consider, too, the work of Douglas Barbour, whose emphysematous “breath ghazals” from Breath Takes give us expulsive locutions like “Aaahh,” “ffmmm,” “eff” and “huh.”

Admittedly, McKay is rather more sophisticated in his manner and prosody, his customary architectonic. And he is full of advice and prescriptions. Like his “Knife” in Camber, we must be grateful for what we are about to take, which is to say, give back in reverence to the ineffable which sustains, despite the fact that the knife owes its existence to the mining and energy sector; or like the canoer paddling the numinous in “Precambrian Shield” from Field Marks, we should consider “plunging once again into transparent/unintelligible depths.” One way of doing so, it appears, is to utter the unutterable. His admonitory message in “Song for the Songs of the Common Raven” from Angular Unconformity, “Watch your asses, creatures of the Neogene,” seems a trifle odd for a votary of the Global Warming supposition since the Neogene Period saw the beginning of dramatic cooling. In Strike/Slip, he asks “Who are you?” and answers, “You are the momentary mind of rock,” a line reprised in a subsequent phrase “Heart full./Head empty,” conceits that seem unintentionally apt. Curious how a kind of bathos sneaks into the ecolect. Seabeds may “rear up into mountains” but the poetry remains sedimentary. And speaking of mountains, how different, say, from Gerard Manley Hopkins’ marvelous sonnet passage

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap

May who ne’er hung there. Nor does long our small

Durance deal with that steep or deep…

with its air of dread, poignancy and mnemonic power, and how it rappels “steep or deep” into the mindscape.

As McKay argues in an essay for Making the Geologic Now, riffing off philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, “the intention of culture…has been all too richly realized, that there is little hope for an other that remains other, for wilderness that remains wild. It implicitly acknowledges that there will be no epoch called the Gaiacene.” In order to assure a revivified nature, we must cease “digging up fossilized organisms and burning them, effectively turning earthbound carbon into atmospheric carbon, drastically altering the climate.” Global warming, aka “climate change,” dogmatically accepted as a fait accompli without examining the mounting scientific literature calling it into question, is characteristic of the eco-evangelists playing the carbon game. We are called, McKay writes, “to amend our lives, to live less exploitatively and consumptively.” Fair enough. But we are not called to study and weigh the evidence pouring in from reputable sources to the effect that Big Green has replaced Big Oil as the corporate predator du jour and pre-eminent environment-polluter. In Cracking Big Green. Paul Driessen shows definitively that the Climate Industrial Complex is a $2 trillion per year business based on a “steady diet of false information and alarmism.” But you wouldn’t know it from the diktats of the accessory IPCC, the complicity of Big Government and the canticles of the Wilderness People. (See Note.)

One must give McKay credit for some beautiful prose, however, as in his Introduction to the volume Open Wide a Wilderness: Canadian Nature Poems. The trouble is that, although “nature poetry” is an inescapable response to the pioneer struggle with an estranging environment as the poet experiences it, it falters on three fronts: with only a few exceptions, it does not tend to yield memorable verse, with lines that stick aphoristically in the mind; it is basically a one-note poetry, perhaps a long melismatic note, but still one note; and it exhibits little comprehension of the actual necessities of decent human living in an industrial and technocratic society—a society which provides the wherewithal of life and which these same poets serenely take for granted.

Obscure poets have also joined the madding crowd, exemplifying the tedium of the medium. In Madhur Anand’s Regreen: New Canadian Ecological Poetry, Mari-Lou Rowley gives us “Tar Sands, Going down”:

Look up! look way up—

nothing but haze and holes.

Look down!

bitumen bite in the

neck arms thighs of Earth

a boreal blistering,

boiling soil and smoke-slathered sky.

Writing in The Capilano Review, Kim Goldberg, affirming her Cascadian virtue, informs us that “the notion of ecopoetry has picked up currency in recent years as the ecological crisis heightens along with public awareness and concern” and refers to Regreen as “an impressive anthology featuring 33 poets addressing environmental matters. (Her “full disclosure” informs us that she is one of the contributors.) The word “impressive” may not be wholly accurate. There isn’t much to a poetry saddened by “driftwood/floating from the millennium” (Don Domanski, “Owl”) or perplexed by landscape reduced to a dinnerplate moose circling the rim (Ross Leckie, “The Natural Moose”). There are far too many examples of such pampering doggerel littering the Canadian ecoscape to cite in a brief compass.

Of course, not all of this is risible. It is only fair to say that celebrating the natural world and wishing to preserve its beauty and integrity is the desire of every sensible and sensitive person. Who doesn’t appreciate green space? Within what we might call the parenthesis of sentiment, the wilderness poets, heirs to the Romantic tradition rendered raw and demotic, may be commended for their commitment to earth and sky, to bird and leaf and lake. Jan Zwicky’s charming “Bee Music” from Robinson’s Crossing is a delicate expression of subtle and loving perception. To sense so refined a communion with nature and wilderness cannot in itself be faulted. In Thinking and Singing: Poetry and Practice of Philosophy, Tim Lilburn, perhaps the most philosophically inclined ecopoet, insists on the need for “contemplative attention” to the earth, a “permeability before astonishing otherness,” and resistance to industrial pillage. “There is a form of belonging to land,” he writes in The Larger Conversation, “that is deeper than having a local address. It would be called chthonic citizenship, earth-Belonging.” In other words, as he tells us in “Contemplation Is Mourning” from Mosewood Sandhills, the time for a new understanding is upon us. “We have come to “the edge of the known world and the beginning of philosophy.”

This is all well and good, a kind of Orphic Politics or mystical epistemology, a franchise of enlightened civics—at any rate, so far as it goes. But it does not go far enough, lacking a sense of proportion, a saving pragmatism, a recognition of the interwoven complexities of nature and society, of the manifold of human needs, of the dialectic of meditation and prosperity, and of both the noble preservation and necessary exploitation of the environment.

Nature is the base, the garden-cum-wilderness, but it is human ingenuity and labor and struggle and suffering and stubbornness and attention and courage and husbanding that have given us the means of survival and the prospect of flourishing. That is what should also be celebrated. The eco-crowd tends to see human beings as marauders and exploiters, forgetting two things: that nature is not only benevolent and mysterious but also feral, “red in tooth and claw,” and does not have our interests at heart; and that a vast constituency of innovative, hard-working, entrepreneurial and economy-building human beings have provided for the life we enjoy and that many of us assume as somehow given. We thank nature and are grateful for its abundance. We neglect to acknowledge our farmers, butchers, livestock keepers, food processors, refrigerator experts, electrical technicians, truck drivers and transport engineers, our marketing professionals and the energy sector as a whole that render abundance accessible. When the lights go out, the winter furnace shuts down and the shelves go Mother Hubbard, our wilderness poets may begin to reconsider.

Touting what McKay calls “the visionary experience of wilderness as undomesticated presence,” wilderness poets remain oblivious to the shadow side of their exquisite posturings. There are two significant problems with the poetic eco-cult. The first, as suggested above, is contradiction. For example, an expository volume like Ornithologies of Desire, focusing on McKay’s verse and his fascination with birds—Birding, or desire is his breakthrough book—is a primer of “avian poetics” and a celebration of birds as an “authentic form of otherness.” At the same time, these poets, as we have seen, are avatars of Green whose major symbol is the bird-slaughtering wind turbine. You can’t have it both ways. In “Load” from Another Gravity, McKay meets a White-throated Sparrow “exhausted from the flight/across Lake Erie,” and, crouching before it,

Want[ing]

very much to stroke it, and recalling

several terrors of my brief

and trivial existence, didn’t.

McKay might want to read the report of the Ohio Power Sitting Board, which opposed the Icebreaker offshore wind turbine project placed before it by the Lake Erie Energy Development Corporation, citing costs, massive job losses and multiple negative environmental effects. Similarly, the project was opposed by the Black Swamp Bird Observatory for the threat it posed against “avian and bat species.” The White-throated Sparrow may not have survived the Lake Erie turbine blades for the poet’s moving commiseration. McKay might also want to reflect on the damage caused by many of his birth-province Ontario’s 8000-plus wind turbines, labeled by locals as “bird blenders.”

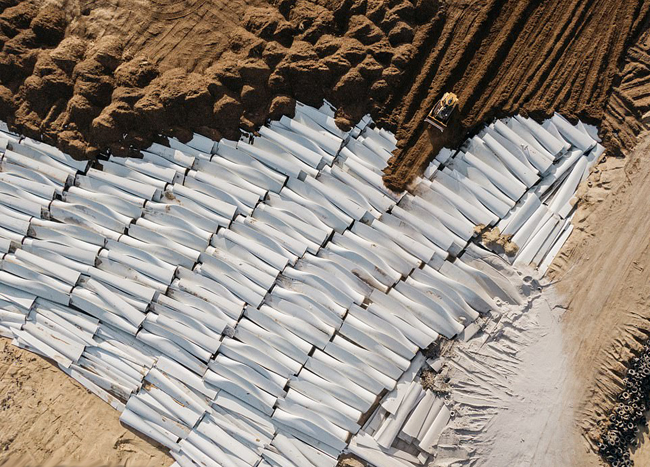

The second problem is a kind of ethical blindness. Largely dependent on government grants and prizes channeled through the Canada Council and, for many, lucrative university positions and appointments, our anti-industrial eco-prophets have little understanding of economic reality, are indifferent to the major contribution of the energy industry to the Treasury from which they draw their salaries and endowments, and are cavalier about the hundreds of thousands of jobs that would be—are—lost as a result of their faddish enthusiasms. They do not “get” the unpalatable fact that nature must be controlled if it is not to control us. They do not realize that “renewables” like solar and wind are highly ineffective, prohibitively costly and environmentally damaging, requiring dumps and landfills for unrecyclable turbine blades and solar panels that are being filled to the brim (Figure 1). And they are completely unaware of the technological improvements to oil extraction and pipeline delivery that have led to increased environmental safety.

As educated people, they have no excuse for their ignorance of economic and industrial realities and their sanctimonious disregard for the welfare of their fellow citizens. “Caring for nature,” Bruce Thornton reminds us in Decline and Fall: Europe’s Slow Motion Suicide, “is the luxury of those who aren’t worried about eating for another day.” Not that caring for nature is somehow to be frowned upon, but that the pious quest for wilderness atonement and environmental temperance—for Lilburn’s “green martyrion, the place where language buries itself,” as he puts it in Mosewood Sandhills—is a species of blue-ribbon puritanism essentially enjoining us to decolonize life.

What The Canadian Encyclopedia says of Lilburn’s “living with decorum as opposed to violent appropriation” would apply to the Wilderness School in general. “Living with decorum” is often the privilege of the wealthy or the subsidized, but the world is a rough place that must be constantly negotiated, requiring obligatory if not always obliging trade-offs. When the culture goes soft or aberrant or faddy, what is needed is not compliance with voguish shibboleths and eccentric cerebration but unsparing tough-mindedness and common sense. One thinks of G.K. Chesterton’s poet-sleuth Gabriel Gale in The Poet and the Lunatics, who eschews eccentricity and opts instead for “centricity,” restoring prudence and sensible values to the Commonwealth.

Regrettably, the vast majority of contemporary poets in this country—as in many other countries—do not form part of the long poetic tradition of cultural skepticism and critique, but have become charter members of the fashionable movements of the time. They write poetry, a little of it reasonably good if not particularly memorable, but it is a poetry that is no longer wedded to uncompromising intelligence, economic praxis, political insight or the service of what Matthew Arnold called in Culture and Anarchy “the best that has been thought and said.” It is not a poetry that exemplifies Martin Heidegger’s dictum in his essay What Are Poets For?: “The song of these singers is neither solicitation nor trade.” And it is surely not a poetry that the proverbial “common reader,” whose phantom presence is a custodial check on habitual obscurity, could ever possibly understand, appreciate, absorb or recite.

Our poetic leapers are writing a species of wilderness poetry in the pejorative sense, for the wilderness that would arise were they effectively persuasive would be an economic disaster and an eco-social wasteland, T.S. Eliot’s Waste Land in its current cultural incarnation. I confess that this sort of thinking is rather too recondite, fine-spun and metaphysical for my taste, and when it segues into the clunkiness of stark, menacingly concrete, 280 feet high, bird-chopping, landscape-desecrating wind turbines and carcinogen-leaking panel arrays, I find it grotesquely inappropriate. It gives the lie to the ruminative ecstasies of our poetic theorists who cradle the frisson of epiphanic otherness. Just as wind and solar betray a vital and indispensable dependence on fossil fuels for their construction, maintenance and support, there is a delectable irony in the fact that our poetic “desert fathers” and “earth mothers” depend for the materials, production, promotion and circulation of their works on precisely the energy infrastructure they would render desolate and void.

Eliot said it pithily, quoting St. Augustine: To Carthage then I came.

Note

I would recommend that our ecopoets consult, to mention only a handful of authoritative texts, Gregg Hubner’s Paradise Destroyed, Rupert Darwall’s Green Tyranny, Ian Plimer’s Not for Greens: He Who Sups with the Devil Should Have a Long Spoon, Vincent Gray’s The Global Warming Scam, Robert Zubrin’s Merchants of Despair, Bruce Bunker’s The Mythology of Global Warming, Norman Rogers’ Dumb Energy, John Casey’s Dark Winter, Michael Shellenberger’s Apocalypse Never, Tim Ball’s Human Caused Global Warming: The Biggest Deception in History, and especially Paul Driessen’s Eco-Imperialism: Green Power Black Death and Cracking Big Green, which exposes the profitable but ultimately ruinous alliance of ecology, business and government. The truth, he writes, is that massive Green alternatives “are not workable, affordable, green, renewable, ethical, ecological or sustainable,” though they are obscenely lucrative for their proponents. These are sober books written by top-tier scientists whose scrupulously researched and fact-filled analyses trump the ethereal speculations of the wilderness poets, whose work is marinated in overwrought solicitude.

__________________________________

David Solway’s latest book is Notes from a Derelict Culture, Black House Publishing, 2019, London. A CD of his original songs, Partial to Cain, appeared in 2019.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link