Chemical Weapons, A Romance

by Eric Rozenman (April 2019)

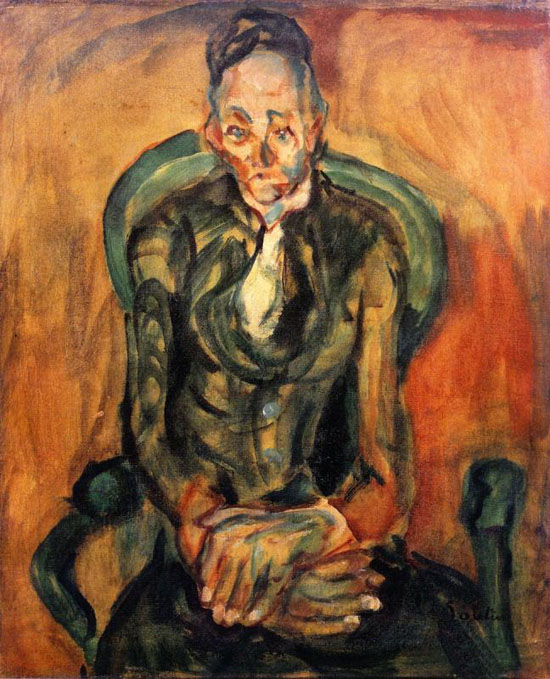

Seated Woman, Chaim Soutine, 1923-24

It was Veterans’ Day, 1990 and though the office, like most of the rest of Washington, D.C. was closed, he had decided to come in, at least for the morning. Something always needed to be done, something that in the private, for-profit world would have been of little consequence, but in the universe of Jewish non-profits, was urgent. And he knew that the fewer people in the office, the more he could accomplish. At least, that’s what he told himself. He punched the answering machine.

Click. “Joseph, this is Juergen at American Eurocars. The Volvo needs a new cluster gear. Sorry. Call me first thing Tuesday.”

Click. “Joseph, this is Mohammed at First USA Bank. We’ve got another notice about inadequate withholding from the D.C. Department of Taxation. The business account’s fouled up again. Call me ASAP.”

Click. “This is Pnina from Mail America. Joe, the returns on the direct mail piece about chemical warfare are fantastic! Over seven percent response, $85,000 in the first five days! Call me when you want to celebrate!”

Click. “Not in, eh? Just what I’d expect from a Jewish organization. What’s your excuse this time, a federal holiday? I wish I had a holiday from all my tsouris.” Here the querulous voice, that of an old woman, dropped to a whisper:

“I won’t give you my name, but my unlisted number is 213 653-5151. That’s Los Angeles, California. If you’re going to call back, make it before 12:15 p.m. That’s Los Angeles time. In California.”

Working on the holiday was his excuse to escape three females at once—his wife, four-year-old daughter and the baby. He suspected that a main reason women were intent on entering the outside workforce was not so much career fulfillment or even economic necessity, but to infiltrate and neutralize the terra incognita to which their men always before had been able to flee and where, unfettered, they could act like, well, not like women.

Read more in New English Review:

• Dirtdogs

• Three Bucolics

Joseph Netherlander switched off the answering machine and picked up the telephone. The real calls could wait until tomorrow. Juergen and Mohammed would not be at work on Veterans’ Day and probably not Pnina, exuberant, narrow-waisted Pnina, either. But the unreal call, that was for now. Besides, the old woman’s voice had reminded him, vaguely, of someone else, younger, who had whispered into his ear on summer nights fifteen years ago. Someone who, in agitated sleep, would thrash nearly from one side of the mattress to the other. Her voice, though stronger than that of the old woman on the answering machine, had the same breathless rapidity, the strained coyness that periodically dissolved into half-wails. He recognized it as the vocal stigmata of the manic-depressive.

So, with Sandee Smolensky on his mind, her long, lean, obsessively tanned body and abject submissiveness, willing to do whatever he so much as hinted at—so long as he would spend every moment away from work, awake or asleep, with her—Joseph Netherlander dialed 213 653-5151. He was still musing over Sandee, her bicycle racer’s legs, her thick, wavy, jet-black hair, her eyes still terrified from the childhood sight of her father a suicide in the front closet, when the old woman answered.

“This is the American Israel Political Affairs Group in Washington,” he said. “You left a message on our machine?”

“I’m terribly frightened. You sent that letter about chemical warfare? When are we going to wake up? They’re trying to kill us again. I’m frightened. Terribly frightened.

“But you made a big mistake. You sent it to my husband, Mr. Gabriel Berlin. Well, let me tell you something. Mr. Gabriel Berlin never gave one dollar, not one penny, to help the Jewish people!

“You didn’t know I was divorcing Mr. Gabriel Berlin, did you?” It was an accusation, not a statement. “Well, I am. We’ve been separated since December 24 last year. That’s when the trouble started. That’s when they threw us out of Hebrew Senior Home Number Two. I’ll bet you didn’t know that . . . of course you didn’t.

“Well, I plan to send chai to your organization, the Israeli-American League—”

“American Israel Political Affairs Group,” Joseph Netherlander broke in.

“—Committee, Congress, League, whatever. I’ll send chai to help Israel and the Jewish people. No thanks to Mr. Gabriel Berlin, who never was a mensch. Neither was my first husband; at least he died young.”

Joseph Netherlander looked at his watch. Another five minutes, that was all he could give the old woman. Ten at most. He had to draft a follow-up solicitation to the chemical weapons letter, make it a real one-two punch. The president of his board had been on him, digging at him for the organization’s flat direct mail fund-raising. This latest appeal, with Yasser Arafat’s grinning face on the envelope, Saddam Hussein’s likewise at the top of the letter inside, with the question “Why are these men smiling?” in bold black letters, would shut up the arrogant bastard. Eighty-five thousand dollars in the first five days? Unheard of! Yes, this would shut him up—for about a week, until he hit upon a new complaint, which he habitually did.

Chai, Hebrew for life, had the numerological equivalent of 18. So, 18 and multiples of it had become traditional amounts for charitable donations. “Mr. Gabriel Berlin did not understand the connection between life and charity, but we do, don’t we Mr., ah, what is your name?”

“Netherlander, Joseph Netherlander, Mrs. Berlin.”

“Don’t call me Mrs. Berlin!” she screamed. She hurt his good ear from three thousand miles away. “Call me Irene,” she said sweetly, the manic’s change instantaneous. “It’s not my real name, but I’ve used it for the past forty years, ever since Justice Brandeis’ grand niece helped me return to Judaism. Did I tell you about her, about Felicia Frommer? I used to sit for her when I was a teenager growing up in New York.”

He looked at his watch again. He ought to break this off. “Listen ma’am, I really must—”

“Yes, I know, you’re busy. I won’t keep you. I’ll let you go. You’ve got to get back to work. But you’ll get your check. I send checks to all the organizations. I can only afford to send $18, but I always send something.

“When we got married, my husband—the second one, Mr. Gabriel Berlin—didn’t give the rabbi, David Lightner, a thing. That’s the kind of man he was. Is. Always will be until, thank God, he’s dead. And Rabbi David Lightner wouldn’t take anything. He just said ‘go and be happy and raise a Jewish family. That’s the best gift for me.’ Of course, we never had any kids but the one . . .Did you know I was an unwanted child, been unwanted all my life? How do you think that makes me feel, Mr. Netherlander?”

“Ma’am . . . ” He tried to respond, but she was talking faster and faster, her voice going higher, her breaths coming in quick gulps. Like Sandee Smolensky—except in those first moments, late on a hot summer night. Then, having raced her bicycle against no one but herself for miles, after shoveling down yogurt, after chain smoking and non-stop talking, after sometimes bruising sex—he could never think of it as “making love,” it was, to her even more than to him, more like taking possession—she would sleep deeply, and breathe deeply, regularly, easily. But only then.

“So I took a little of the wedding money, which wasn’t very much—this was 1958, I think, yes, 1958 for sure, and neither his family nor mine, what was left of them, had money—and bought Rabbi Lightner a waffle iron and gave some to tzedakah. I had to do it because Gabriel Berlin was not a mensch. He had an M.B.A. from N.Y.U. and I never graduated from college, just a year of teacher training after high school, so I never understood the numbers too well, the savings and the checking and the bills. He lorded that over me. And to think that I let him get away with it, because I know now I can do it. But I never had any self-confidence.

“I was born 15 months after my brother . . . ” this was, he realized, the same separation between Sandee Smolensky and her brother, the dancer “. . . and my parents, my father, let me know in every way that I was unwanted. My mother believed that bubbe-meise that you couldn’t get pregnant if you were nursing. Well, of course you can. Not as often—I read a story in a medical journal in Dr. Rothman’s office over on Pico Boulevard about it just last week—but you can. I mean, here I am, after all. She was a big Yiddishe mama, my mother, and it was because of her influence that I eventually came back to Judaism. She and my best friend from childhood, Esther Gold. Esther lives in Jerusalem now. And Felicia Frommer.”

“Ma’am, I’m sorry, but . . . ”

“Yes, good-bye.” And Irene Berlin slammed the receiver down. If that was really her name.

Some minutes later Joseph Netherlander had stopped staring at his telephone and was engrossed in the electronic letters glaring from the monitor of his word processor. The phone rang. Damn, he had forgotten to turn the answering machine back on!

Read more in New English Review:

• In Defence of Trump and Others

• Donald Trump is an Existential Threat to the Managerial State

• ISIS Caliphate Falls, but Could There be a Second War in Syria?

“I didn’t want you to think I was rude. I know you have your work. Men always have their work, unless they get sick. Women just have their lives. Anyway, Esther lives in Jerusalem, made aliyah years ago with her husband, her first husband, who was still alive. Some people have all the luck. Anyway, you know it’s cheaper for me to call her than for her to call me, something about Israeli rates and taxes. Esther’s always complaining, but she loves it there. Has her own gas mask, sealed room, everything. So I don’t waste my money on therapists and social workers anymore. I just call my friends in Vancouver or Las Vegas or Jerusalem. It’s cheaper and makes me feel better. Sally used to be a dancer in Las Vegas. Of course, that was a long time ago. Then she became a bookkeeper in one of the casinos.

“I’m taking a course now at Classes for Older Americans. There aren’t many Americans older than I am, I always say. I’m going to go back to work as a pre-school teacher’s aide, half days. I’ll be making seven dollars an hour. You know, I used to charge only one dollar an hour to watch Justice Brandeis’ grand niece. It was a lot of money then. But they said I was worth it. I’ll never forget that. So with that and the $477 a month I get from Social Security—and some alimony Mr. Gabriel Berlin is going to have to pay—if the shyster lawyers don’t take it away from me—I’ll have more than $1,050 a month. Maybe $1,110. Then I’ll be able to send you another check. You and the Simon Wiesenthal Center. Their mail frightens me almost as much as yours does, Mr., ah . . .”

“Netherlander, and I really must get back to work now . . . ”

“Irene. I told you that you can call me Irene. Anyway, I have confidence about numbers now, not like when that fat third grade teacher, Mrs. Marks, Mrs. Lillian Marks, made me stand in front of the class when I didn’t know the answers in arithmetic. Do you know what it’s like to be eight years old and unwanted and not know the answers in school, Mr. Neanderthal?”

He did not. If there was one thing Joseph Netherlander, first child of young and doting parents, knew, it was the answers in school. And maybe the only thing, he reflected.

“Ma’am, please, tell me how I can help. I’ve got to get back to work.”

“Yes, of course, of course. I won’t keep you, won’t keep you, won’t keep you.” It was singsong, lilting. The old woman had a musical voice, or had had one once.

“I called because I’ve been carrying around a letter you sent, the letter about Yasser Arafat and the lies he’s telling and how everyone but you believes him. I don’t believe him either. It’s so obvious he’s a liar. He reminds me so much of my husband, my ex-husband, Mr. Gabriel Berlin, and everyone can see through him. Well, almost everyone.

“The night we got thrown out of Hebrew Senior Home Number Two, December 24, did I mention it? They couldn’t make up their minds between him and me, so they chucked us both out. That’s why I carry your letter with Arafat’s picture, and the picture of that other liar, what’s his name?”

“Saddam Hussein.”

“Right. Insane. They even look alike.”

“Who, Arafat and Saddam Hussein?”

“No, of course not. Saddam Hussein and my soon-to-be ex-husband. Of course, he doesn’t have as many wrinkles or gray hair.”

“Your husband?”

“Don’t be foolish. Mr. Hussein. My husband’s a little old wrinkled Jewish man. You know the type. Hebrew Senior Home Number Two is full of ’em. Ever seen a Jewish man age like Charlton Heston? I didn’t think so. Now that insane fellow, he’s actually not bad looking, don’t you think? I mean, for an Arab.

“Well, after they threw us out, it was one crummy senior hotel after another for months—until last week, when I got this place. It’s nice and clean, but I’m alone, all alone, alone.” She was lilting again. “And then your letter about chemical weapons came. The post office had forwarded it, but it was really an omen, like HaShem had sent it. And so every time I see Yasser Arafat on the news, or that insane fellow, I think of Mr. Gabriel Berlin and poison gas.”

There was a click on the line. “Excuse me,” the woman said, “at my new place here I have call waiting. Let me see who it is and I’ll get right back to you.”

She was gone. Now who was playing with whom? He looked at his watch again, then at the phone. This was the perfect time to hang up, turn on the answering machine, and get to work. But he hesitated. No, that would be the coward’s way, he told himself. And this is like some indirect payback from Sandee Smolensky for hanging up on her that last time, when she was crying and laughing simultaneously again. Besides, you’re enjoying this, you morbid fool.

“So on December 24, that’s Christmas Eve, can you believe it” —she was back—“I wasn’t feeling too good. I asked that son-of-a-bitch, Mr. Gabriel Berlin, to get me a dish of ice milk. He wouldn’t. So I shouted at him. He shouted back. I shouted louder. He shouted even louder. I threw something at him. That’s when he turned over a chair and started jumping up and down. Then he grabbed my arm, hard. He bruised it so it turned black-and-blue, and yellow around the edges. I screamed.

“That’s when Mrs. Finkelstein, who lived in the little apartment below us, and old Ike Kornblatt, the survivor—at least he claimed he was, I never believed him, he was always talking about in the camps this, in the camps that, but didn’t have a number on his arm—who lived next door, called the super. She called the police. You know it was a good fight when Kornblatt could tell—he was a little blind and half-deaf. A very obnoxious man too, always pinching me when my husband had his back turned.

“Anyway, they threw us out. The supervisor said we’d been warned too many times before. Warned, schmarned. That’s your Jewish charity for you, Mr. Joseph. They wouldn’t even give us our deposit back. Said we were lucky they didn’t sue for damages. They do that to everyone who leaves. So what do you think of your Jews now, Mr., ah . . . ”

“Please ma’am, tell me what you want. I’ve got to get back to work . . . ”

“Work, working, work,” she sang. “That’s all you men know. Don’t kill yourself, Mr. Joseph, with work.”

“Netherlander. Joseph Netherlander.”

“Of course, that’s something Mr. Gabriel Berlin was never in danger of, working himself to death, I mean. That’s why I could never spend much time with Sally in Las Vegas. She was a wonderful dancer. And those high heels and feathers, they made her legs look great. You know, in flats she really wasn’t that much to look at, but with heels and make-up . . . you know how it is.”

He wished he did. But after their first child, his wife forgot about make-up. After the second, more or less about him.

“Well, a month after that, after Christmas Eve, I decided to keep my New Year’s resolution about helping other people.”

This woman astounded him. She must be 80-something, and she’s still making—and keeping—New Year’s resolutions?

“I went to Love Is Feeding Everyone, you know, that charity on Sunset Boulevard that Dennis Weaver, the actor, started, and a bunch of show-business types are running? Well, it was Shabbat, but I went anyway. The Torah says we have to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, right? I could have sent a check, a little one, but I wanted to go myself, to do something for other people. So I stepped off the curb and must have put my foot down wrong, because I twisted my ankle and fell. I smashed my knee, my right knee. Maybe I shouldn’t have gone on Shabbat. But I know HaShem wasn’t punishing me because He got me this new apartment, the first decent place since Hebrew Senior Home Number Two.

“I was walking with my walker—this was later—in front of the senior hotel in West Hollywood, a real dump, you know, when a fancy foreign car pulled up beside me. A voice says, ‘Mrs. Berlin, is that you?’ It was Esther Gold’s son, Peter. He’s very rich. You must know him. He probably gives thousands of dollars to your organization, right? He told me he gives so much to Federation that they don’t bother him anymore, just hang his portrait in their lobby. Can you believe it?”

Netherlander could not, but wrote on his notepad: “Peter Gold, Hollywood. Cross-reference major givers lists. LA/UJA.”

“Well, HaShem sent him to me. When he found out what was the trouble, he took me to the place I’m in now, Heritage Horizon Apartments, a building he’s part-owner of which has 24-hour nursing care as well as security, and told them to give me the first three months rent free. It’s true. God made me a miracle. After all these years, me, the unwanted child who was never wanted.

“And once a week, on Friday mornings, we have entertainment here. Last week some folk singers came. They sang all the songs I knew from the ‘40s and ‘50s. Songs I learned at Seward Park High School on the East Side. I knew folk songs then, I was very active. But I didn’t really understand about Palestine, about Jewish politics.

“Once we all went by train to the White House, outside the White House, for a protest. And Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger” —God, can Seeger be that old, thought Netherlander—“sang a song, ‘Please Mr. Roosevelt, Don’t Turn Them Away.’ They meant the Jewish refugees, can you believe it. Roosevelt didn’t like that, no he didn’t, because he was supposed to come out and say a few words to us, but never did. Of course, we knew Eleanor was doing her best for us, so that didn’t really matter. Now after I get settled here, and finish the alimony suit against Mr. Gabriel Berlin, I’m going to join that Volunteers for Israel program, go to HaEretz for three weeks and work on an air base or something, and see my friend Esther. Peter is going to set it up. He told me just to call his secretary and she would take care of the details.

“But I don’t know. His secretary is Mexican. I tried to talk to her once already on the telephone, but couldn’t understand her. I had to shout, and I think that upset her. Plus, I was afraid someone here at Heritage Horizon Apartments would hear me shouting” —here the old woman’s lilting sing-song became a querulous whisper again—“and anyway, she wouldn’t let me talk to Peter.

“Right now I’m shopping at the thrift stores, accumulating shmattas so I’ll have something to wear when I go back to work at the pre-school.”

“Ma’am . . .”

“I know, you have to go. I won’t keep you. I’ll let you go. Just do this one thing for me . . .”

“Of course, what is it?” Netherlander asked, relieved that the call was coming to an end at last, that he could do something for this troubled, strange old woman and be done with her at the same time.

“Those chemical weapons you wrote about?”

“Yes?”

“Could you get some for me? Just a little bit, you know. I could increase my donation. Los Angeles is a dangerous place, and if my ex-husband comes around—and he might, the vindictive bastard—I’ll need to be able to protect myself. I’m too old to learn karate. A little chemical weapon would be just the thing, don’t you think? I’m an old Jewish woman and you just don’t know what kind of hell I’ve been going through.”

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Eric Rozenman is a communications consultant in Washington, D.C. His poems, commentaries and analyses have appeared in New English Review and numerous other publications. He is the author of Jews Make the Best Demons: “Palestine” and the Jewish Question.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast