Coming to America: The Cuban Freedom Flights, 1965-1973

A Portrait of Exile

by Pedro Blas González (January 2023)

The Gulf Stream, Winslow Homer, 1899

People who bite the hand that feeds them usually lick the boot that kicks them.

The hardest arithmetic to master is that which enables us to count our blessings.

—Eric Hoffer, Reflections on the Human Condition

America

In the skewed mind of her detractors, America is merely an economic system. This cynicism distorts American democracy—deliberately. Criticism fueled by bad will puts on display a visceral misunderstanding of history, human nature, and the human person. According to her defamers, America must be chastised for not being a universal welfare state.

America is the culmination and practice of noble ideas. For me, America enables man the cultivation of transcendent values in a world rife with bad will. This is all I demand from the land of Washington and Jefferson. The land of Lincoln tames the human tiger.

Albert Camus is correct that what the world lacks most is people of good will. Yet people of good will have made America a nation of self-governing citizens who seek nothing more from the State than the freedom to exercise primal and existential freedom. America offers its citizens the promise to live dignified lives.

America safeguards the sanctity of moral goodness from the ravages of human history—from the claws of the perennial human tiger.

America pays tribute to the most noble aspects of the human person. Inspired from John Locke’s poignant understanding of the human psyche and will, America was conceived as a place where the Pandora’s Box of human barbarity could be kept at bay. This is one reason why America personifies accumulated social-political wisdom. America was not founded on Marxist theory, the quest for world domination, or the hapless dreams of utopians.

My Arrival in America

My family arrived in Miami, Florida at 8:45 a.m., on Friday, December 4, 1970.

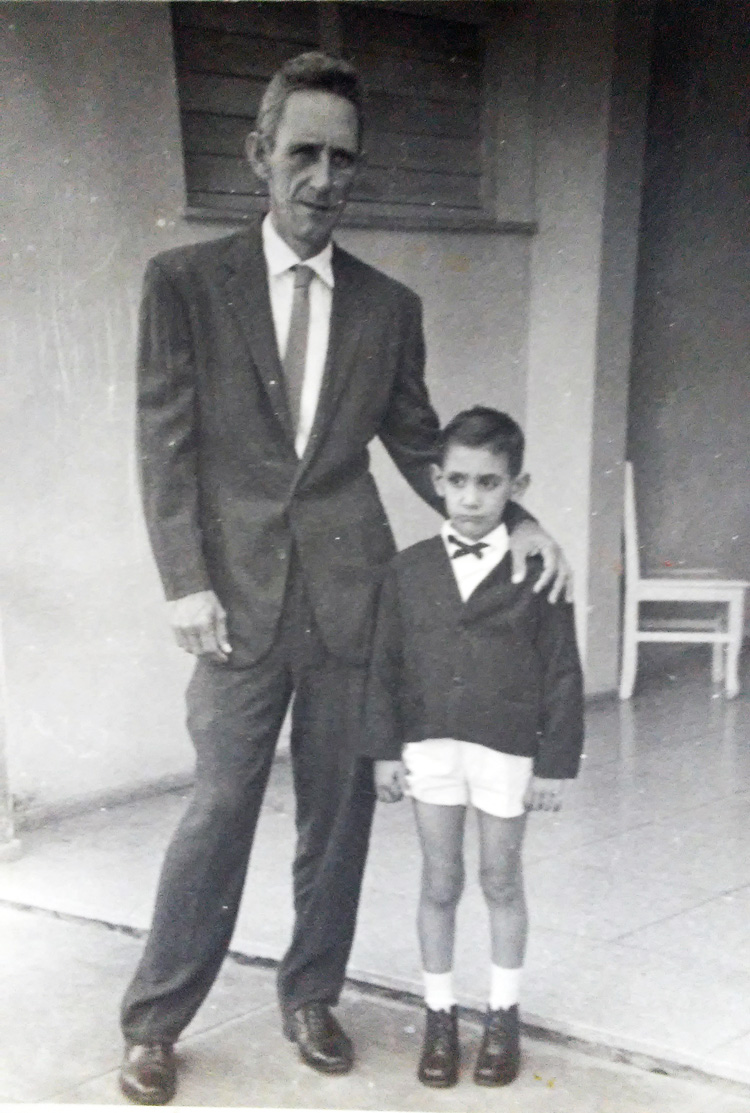

After serving over four years as a political prisoner in Castro’s communist police-state, in the Escambray forced-labor camp, my father was claimed by an aunt and uncle who lived in the U.S. since the early 1950s. My father’s crime? He was a practicing Catholic; he and my mother refused to raise children in a communist country. At that time, to enter the United States from Cuba legally one had to be claimed by a relative.

We came to America on one of the Freedom Flights (Vuelos de la Libertad) that President Lyndon B. Johnson established in late 1965. Between 1959, the time of the communist take-over of Cuba, and 1962, over 200, 000 Cubans fled the communist island on small boats and makeshift rafts. This number does not take into account the people who perished trying to cross the Florida Straits. During 1965 alone, 149, 000 Cubans left the island. This was the Camarioca boatlift.

Between December 1960 and 1962, over 14, 000 children, ages 6 to 17, were sent to the U.S. by their parents in what was called Operation Pedro Pan. The children were taken in by churches and private schools. They were placed in foster homes throughout the U.S. Their parents preferred to send the children to America alone than allow them to become the pawns of communist indoctrination and forced induction into the Cuban armed forces.

This mass exodus signaled a massive response to the oppression of the communist government that Fidel Castro created. This was a major embarrassment for communism in Cuba and throughout the world. It still is. The exodus initiated a brain drain and destruction of the Cuban work ethic that Cuba has never recovered from with the Soviet ‘new man’ – post Castro’s takeover.

After taking notice of this steady exodus of Cubans, including many defections, President Johnson took Castro to task for claiming that no Cubans wanted to flee Cuba.

The Cuban Freedom Flights

On October 3, 1965, Johnson embraced the plight of Cubans who desired to leave the communist island: “I declare to the people of Cuba that those who seek refuge here will find it.” This was the beginning of the Freedom Flights. The flights took effect in 1965 and continued to 1973. In eight years, over 250, 000 Cubans gained their political freedom via those two-a-week flights.

At the time, Cubans harbored the illusion they would reunite with their children and other loved ones in the near future. Few people in Cuba imagined the strong-arm violence and long-lived terror they would be subjected to under communism.

No one imagined that 64 years later Cuba would still be in the repressive throes of a communist dictatorship, in a time of mass media and the Internet. Why is this? Despite the infrahuman life that communist dictatorship has forced upon the Cuban people, Cuba continues to be the darling of Western intellectuals and postmodern radical ideologues.

The Mariel boatlift of 1980, when 125, 000 Cubans arrived on U.S. soil, was another exodus of Cuban refugees to the U.S. The history of the many phases of Cuban refugees coming to America is well documented.

Of the millions of people who reach American shores every year, few can be considered political refugees. People come to America because they recognize that she can provide them with a better life. However, the circumstances and pathos of political refugees is unique, especially when compared to other forms of immigration to America.

Cubans of the Cold War era are proud of being political refugees. I refer to my childhood experiences in the United States, in the early 1970s, as the ‘handout generation.’ Cuban refugees in the U.S. wore second-hand clothes donated by well-wishers and Catholic institutions like Saint Vincent DePaul.

Cubans who came to the United States on the Freedom Flights brought all their belongings with them in several suitcases. Property and private items left in Cuba was confiscated and given away to communist-party members. This is one way that Cuban communism began to forge the new socialist man: resentment and ‘egalitarianism’ with a hammer. Envy, resentment, and the politics of suspicion—the building-blocks of communism—are rewarded by destroying the lives of others.

People who desired to leave Cuba and not live under communist oppression were considered persona non grata. We were called gusanos (worms), expendable parasites.

Gusanos were imprisoned, tortured, and murdered by firing squads because they were considered enemies of the state. Their relatives and children were harassed at work and school. The homes of gusanos were under constant surveillance by state security forces. After Castro took power, neighborhood committees were created to report on activities at the home of gusanos. State-sanctioned snitches traded dignity for the morsels of power the communist regime offered them.

Envy and resentment are the foundation of communism. The German philosopher, Max Scheler, aptly demonstrates that resentment is a destructive motivator of human behavior.

Members of the Cuban Neighborhood Committees for the Defense of the Revolution are opportunists. By embracing totalitarianism, they flee from the alleged burden of free will. This is one way that communism exploits envy and resentment to consolidate absolute power.

The universality of envy and resentment makes these profound human emotions ripe for fomenting communism, for envy and resentment have served as the culprit of crime and murder since the dawn of man.

Communism converts envy and resentment into criminal arrogance. While envy and resentment eventually consume their host on a personal level, these emotions are converted into institutionalized—alleged public virtue—through communism’s dialectical materialism.

People who come to America as political refugees enjoy a form of self-worth and dignity they cannot attain in their place of birth. To comprehend the facts and nuances of Cuban history under communism, one must first come to the realization that Cuban history, from 1959 to the present, owes its criminal pathology to soviet Bolshevism.

While Cuban communism imprisoned and expelled us for being gusanos, parasites who did not want to share in the ‘glory’ of collectivism, America welcomed us with open arms.

What Cubans seek from the land of Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln is to exist as dignified persons. This is a modest wish, given the intrusion into personal liberty and the destruction of family life in Cuba under Castro. America returns hope and liberty to people who have been disenfranchised by totalitarian violence against the human person.

Upon arrival in America on that December morning in 1970, my father, as many Cubans before and after, kneeled and kissed American soil. This simple act of gratitude went deeper than most people can appreciate.

Father was arrested as a political prisoner after declaring he wished to leave the communist island. Soldiers came to our house in the middle of the night and arrested him for seeking an American exit visa. The presumption of communist governments is that anyone who wants to leave a communist country is an enemy of the state.

Being Catholic, my family held allegiance to a transcendent being other than mother state. This is anathema to atheism under communist rule. On two occasions while incarcerated, the murderous, well-to-do bourgeois, Che Guevara, told my father to his face, “You are going to rot in this prison for your Catholic convictions.” The Argentine revolutionary doctor informed father that there was no room for God in the life of the new soviet man.

My family’s road to freedom was far from easy. We were not wealthy, as many of the people responsible for putting Castro in power, who fled the island first when squeezed by the talons of communism. One day my parent’s dream became reality in a State Department letter:

Department of State Washington, District of Columbia November 21, 1962 Reference is made to your inquiry requesting that a waiver of the Nonimmigrant visitor visa requirement be granted to the above-named person (s). The Department, jointly with the Immigration and Naturalization Service has granted the necessary waiver. If transportation is to be obtained through the Havana office of either Pan American Airlines or KLM Royal Dutch Airlines this letter should be presented there. Therefore, you may wish to send this letter to the person(s) concerned for this purpose.

While the letter is dated November 21, 1962, we would not leave Cuba until eight years later. What ensued from this request was my father’s arrest, endless harassment and humiliations from the Cuban government.

That cool December morning in 1970 we finally found ourselves in America. For my parents, the ordeal of having to leave their homeland was bittersweet. Father left his parents, sisters, and brothers. Mother also left her parents, a brother, and two sisters behind.

Before we were allowed to walk onto the tarmac to board the Pan American Airways DC-7—after three days of waiting at the airport—we were warned not to wave goodbye to relatives who were standing outside the fence. One final humiliation.

I vividly recall father crying. Stopping for a moment to look back at his family, a soldier instructed him to continue walking. Father took out a handkerchief from his coat pocket and pretended to sneeze, quickly waving it in the air as a gesture of goodbye. More humiliation.

In Miami, we were given temporary housing in a building called La Casa de la Libertad (Freedom House), which was located on the grounds of Miami International Airport, but not in the terminal.

My parents contacted people they knew in Miami. As luck would have it, father found a dime on the ground with which he was able to make his first telephone call in the United States.

That same Friday, some friends, also recent arrivals, came by. They loaned my parents five dollars, others ten.

On Saturday more friends came by and loaned my parents addition money. By Sunday night father had collected enough money to rent a small apartment in the northwest section of Miami, practically the only area of the city that refugees could afford.

Monday was our first day in a small rented apartment.

Tuesday morning father went off to work at the O’Keefe trailer factory. My sister and I were enrolled in public elementary school.

First Christmas and a New Life in America

My parents bought a silver aluminum Christmas tree that was beautiful when fully decorated, an activity that mother took great pride and care in undertaking. We kept that artificial tree until 1987.

On Christmas Eve, my sister and I remained vigilant until midnight, anticipating the arrival of Santa Claus. We finally gave up and went to bed. In the morning we found several toys for each of us. This remains one of my most memorable Christmas, especially in light of the sacrifices my parents made.

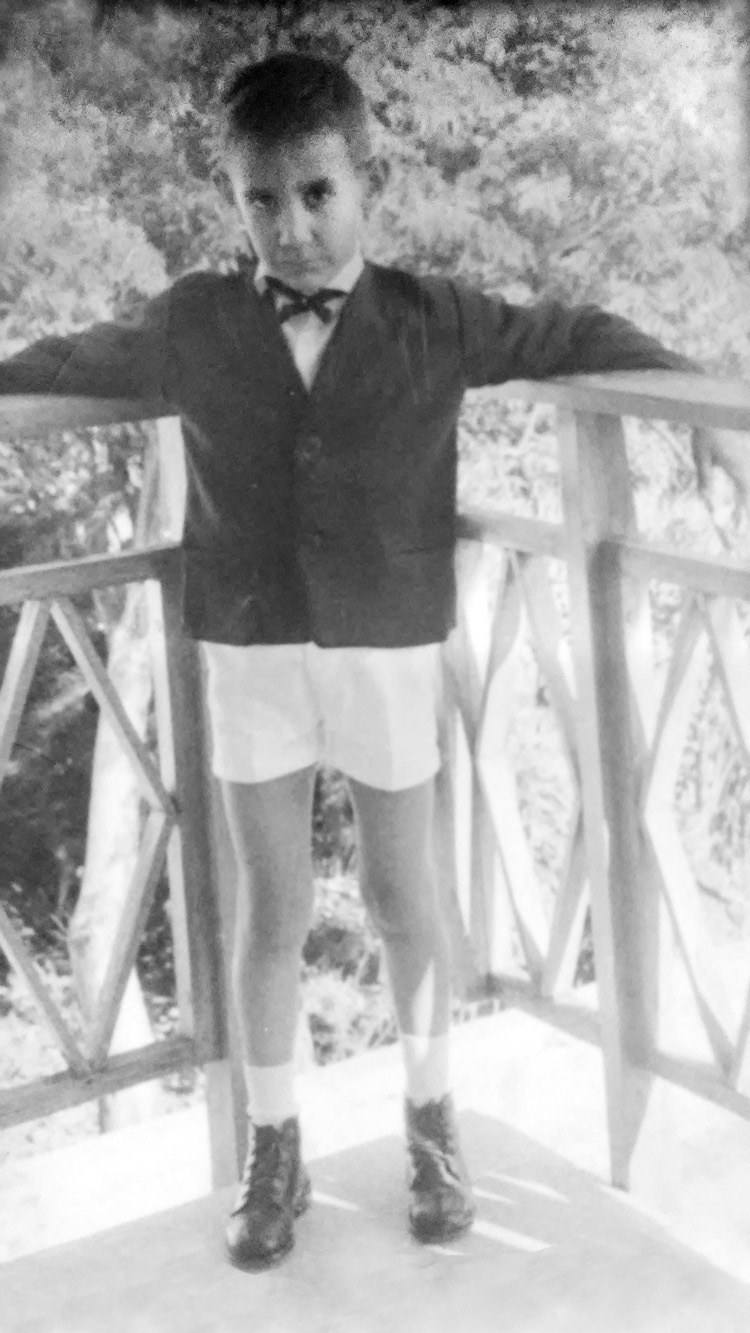

My sister and I were enrolled in catechism at Corpus Christi Catholic church, across the street from our apartment. I continued attending that church for catechism until 1975. There, I received my First Communion. Classes were on Saturdays. On Sunday, the family attended mass. My matriculation in catechism and attendance at Sunday mass at Corpus Christi had a lasting, life-affirming effect in my early formation as a young boy. I cherish my earliest memories.

Our earliest experiences, especially when life-affirming establish the conditions for a joyful future. The child that got off the DC-7, that December morning in 1970, is responsible for the man that I am today. That boy has never left me.

The first six months of 1971 were tense for my parents. They were both forty years old, and starting a new life in a foreign land. They scrambled to find work. Mother was four months pregnant

My parents were always attuned to American life, its customs and gravitas, as well as its frivolity. Father followed American cultural and political news while in Cuba. Upon arrival in Miami, my parents regained their personal dignity that, sadly, they could not enjoy in their native land under communism.

In Retrospect…

As a child, I understood that resistance is the mother of all things human. I can’t imagine a life without resistance, without the inherent pressure exerted by life and the world on our wishes, dreams, and aspirations. This may or may not be the best of all possible worlds, as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the German philosopher contends, for we don’t have anything to compare it to, yet life can be agreeable, nonetheless.

Father always reminded us that America is the land of opportunity, and that we should not take this for granted. In Cuba, especially during the years he spent as a political prisoner, father learned that life is fragile and fleeting. On several occasions he came close to being executed by firing squad for not supporting the murderous ideology that ruled the communist island.

The experiences we value most as we age are informed by qualitative essences, not the visual and sensual events that, in their immediacy, are readily embraced as pleasurable quantities.

The fluidity of life makes it such that we rarely appreciate the memory-infusing importance of the events in our lives, for we are too transparent to ourselves. Such is human existence, a liquid-crystal that obscures the effort that goes into living.

This essay is excerpted from a manuscript titled My America: A Portrait of Exile.

Table of Contents

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast