Darkness Visible in J. G. Ballard’s Concrete Island and High-Rise

by Pedro Blas González (November 2020)

Blue Morning, George Grosz, 1912

In some ways the task he had set himself was meaningless. Already he felt no real need to leave the island, and this alone confirmed that he had established his dominion over it.[1]

—J.G. Ballard, Concrete Island

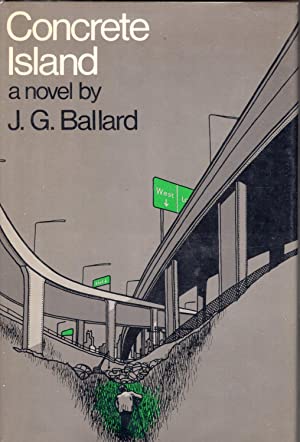

Concrete Island is another of J. G. Ballard’s poignant metaphors for postmodern life. A man crashes his state-of-the-art, late model Jaguar into a road barrier and plunges down into a no man’s land in the middle of three highways.

Maitland, the main character of the novel, refers to this forsaken zone in the middle of London as “the island.” Maitland is hurt in the accident but manages to roam around the island seeking help, eventually realizing that he is stranded.

Maitland, the main character of the novel, refers to this forsaken zone in the middle of London as “the island.” Maitland is hurt in the accident but manages to roam around the island seeking help, eventually realizing that he is stranded.

How can a man become trapped in a wasteland in the middle of a modern city? How can the author convince the reader that such a thing is even possible? This is Ballard’s literary challenge in Concrete Island.

One answer is that the wasteland is a sunken, overgrown land flanked by steep highway embankments. Drivers passing by cannot see Maitland’s car down below. The other is that Maitland has an injured leg. He attempts to climb onto the highway several times but falls. He becomes exhausted and gives up. The rest is literary convention that begs the reader’s cooperation. Like Robinson Crusoe, a castaway in the middle of a concrete jungle, Maitland remains there for seven days.

Daunting metaphors abound in Ballard’s work. They are not the cliché and tired social/political variety that you encounter in the plebeian imagination of most postmodern writers. Ballard transcends the belletristic poverty of postmodern writing by creating visionary situations extracted from the aberrant headlines of contemporary newspapers.

Ballard explores unsavory aspects of human nature that pop psychologists have normalized. Focusing on postmodern man’s fragmented psyche, the author weaves a horrid tapestry of contemporary life and values. His social science fiction paints a picture of man—to use the title of Walker Percy’s novel—as lost in the cosmos.

Ballard’s literary prowess keeps readers interested in his stories because most readers recognize the vile aspects of human nature that the author brings to light. Ballard is not coy about doing battle with the elephant in the room. The author puts on display the slippery slope of moral/spiritual depravity. Ballard’s novels and short stories interlace moral disfigurement with the measurable impact that the absence of a moral compass has on social/political life. Concrete Island reminds us of facets of human nature that prudence knows to be untenable.

Maitland does not realize how morally/spiritually restless he is until he becomes isolated on the concrete island. His forced stay on the island is yet another metaphor for Maitland’s inner demons.

Concrete Island is akin to a Catholic confessional, where the sinner has to amend for his sins. However, the twist in many of Ballard’s tales of postmodern degradation and abandonment is that sinners refuse redemption. Instead, they happily embrace the road to perdition.

High-Rise, the Normalization of Moral/Spiritual Monstrosities

The sense of a renascent barbarism hung among the overturned chairs and straggling palms, the discarded pair of diamanté sunglasses from which the jewels had been picked.[2]

—J. G. Ballard, High-Rise

In Works and Days, the ancient Greek poet Hesiod describes the effect that Prometheus’ theft of fire from heaven had on humans. Zeus, the king of the gods was not amused by this sly act. He takes revenge on Prometheus and his brother Epimetheus, Titans who were said to be advocates of mankind.

Zeus introduces Pandora to the foolish Epimetheus, who after lavishly distributing valuable traits on animals, found himself with nothing of redeeming value to offer man. As a consequence of this, Prometheus took it upon himself to offer man fire and the arts, which he stole from heaven. A trickster, Prometheus is said to have molded mankind from clay.

Mythology and fables serve to convey timeless moral and spiritual lessens to man. Lamentably, heuristic instruction has fallen on bad times in postmodernity. Pandora’s box—opening a can of worms in the English idiom—is a moral, cautionary tale of taking sensual pleasures as ends in themselves.

Ballard’s High Rise, like his other engaging post-apocalyptic tales, dispenses with sentimentality, while focusing on what occurs when the coffers of mythology, religious belief, and morality are gutted.

High Rise follows the trajectory of high living—circa postmodernity, 1975. Ballard published High Rise during the Me-generation era, a time that embraced the notion that, if pleasure is good then more pleasure is better.

High Rise follows the trajectory of high living—circa postmodernity, 1975. Ballard published High Rise during the Me-generation era, a time that embraced the notion that, if pleasure is good then more pleasure is better.

Reading High Rise in 2020 vindicates Ballard’s literary imagination. Beyond being a chronicler of twentieth century social-engineering science-fiction—“SF” is a sufficient acronym for the bona fide followers of this genre—Ballard’s perspicuity transcends commonplace literary convention.

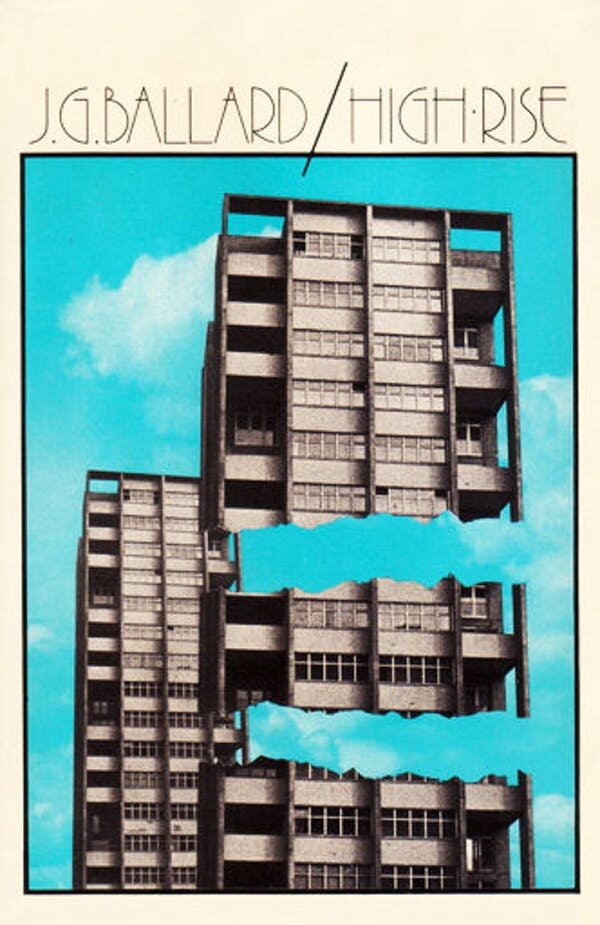

High Rise is the story of a 40-story ultra-modern condominium; its 1,000 units and amenities make the lush apartment tower a world to itself. Yet this is not enough to keep the inhabitants of the building from unleashing their resentment on each other like a tragic-comedy performed by amateur actors at a county fair.

The arrogant residents of High Rise vehemently reject the limits that human reality places on them. Consequently, they turn on themselves and the world-at-large. The brunt of their ire is focused on married couples, mothers and children.

Ballard is the quintessential historiographer of postmodern man’s war with human reality. As the story unravels, readers of High Rise realize that the residents of the fancy condo are all grotesquely dysfunctional.

Yet, this is only the beginning. As the atrocities begin to mount, postmodern dysfunctionality gives way to unadulterated primal savagery. The narrator calls it “renascent barbarism.”

High Rise is a pandora’s box that leaves nothing to the imagination. Because of its lavish commodities, the morally/spiritually decrepit inhabitants of the condominium collude to create an ultra-reality that knows no boundaries, only infinite pleasure. The all-inclusive world of High Rise resembles a postmodern version of Coleridge’s Kubla Khan’s stately pleasure-dome in “Xanadu.”

The quandary of building an altar to postmodern hedonism is that it exhausts itself in disillusion, only to be consoled by appeal to greater pleasures. This is a sorry vicious circle. The assault that the residents of the condominium launch on each other and the building is symbolic of the alleged burden that free will and unrestrained rights pose for postmodern man.

High Rise is a confectionary of secular values taken to their tragic, logical conclusion. The building brings to mind Hieronymus Bosch’s painting “Garden of Earthly Delights,” and what Cordwainer Smith describes in his 1968 novel The Underpeople as “The Department Store of Hearts’ Desires.”

The selfish and calumnious residents of the condominium are always willing to take advantage of each other—reminiscent of that one obnoxious neighbor found in every neighborhood. As the novel progresses, selfishness morphs into criminal behavior, violence, and evil acts.

Ballard does not suggest that the high rise is the source of envy and resentment. On the contrary, the vacuous moral/spiritual values of the residents make the units of the high rise a coveted commodity. The residents of High Rise deserve each other. The building is a stand-in for postmodern man’s moral attrition. High Rise is symbolic of Milton’s description of worldly evil as darkness visible.

Ballard’s dystopian post-apocalyptic stories put on display what happens after truth is hijacked by hackneyed and trite social/political commentary.

Concrete Island and High-Rise are Ballard’s way of depicting a hollowed—out humanity; powerless reason that fails to dissuade the onslaught of content-less opinions. Ballard exposes a world that embraces violence brought on by tribalism and balkanization of identity politics.

In the absence of convictions that carry man from the mundane to a transcendent vision of life and human reality, what remains is raw and freighting psychological terror. High Rise is such a world: the culmination of the normalization of moral/spiritual monstrosities. As a visionary novel, High rise is in step with William Golding’s brilliant novels Lord of the Flies, Pincher Martin and Darkness Visible.

[1] J. G. Ballard, Concrete Island: A Novel. (New York: Picador, 1973).

[2] J.G. Ballard, High-Rise. (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 1975), 99.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

________________________

@NERIconoclast