Days and Work (Part One)

by James Como (March 2019)

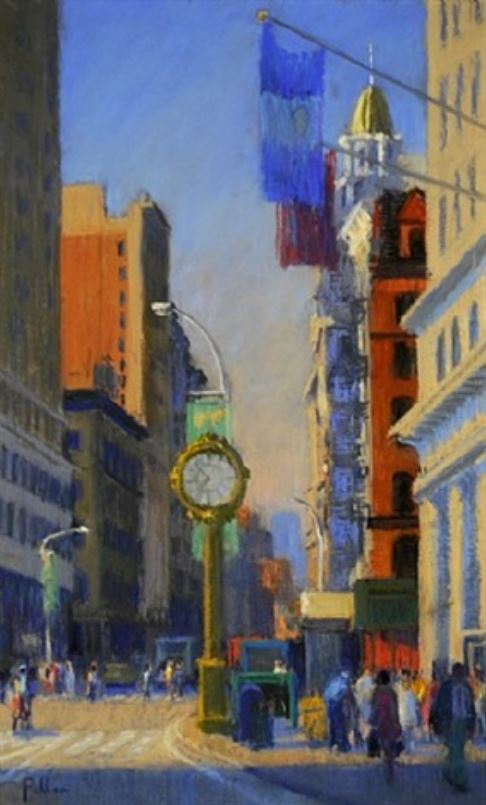

Monday Morning, Joseph Peller, 2012

How odd, upon laying down the same plow on the same little acre after fifty years (1967-2017 at the City University of New York, forty-nine of those at York College, as inner urban as it gets)—how odd that the road well-traveled sometimes seems so short and straight and at others so absurdly long and tortuous.

only in the classroom did he excel. Genuinely stunned, I demurred. Another, quite awful, colleague was recruited and happily wielded the axe.

Read more in New English Review:

• Our Irrepressible Conflict

• The Insidious Bond Between Political Correctness and Intolerance

• Goodness in Memoriam

I recall crises (in the sense of personal turning points) often if not best. My behavior during three of these seemed brave to others but not to me, because I saw no risk and simply assumed that honest action was respected as such. A fourth did require spine, and I remain proud to have been part of (at first) a small cohort who managed to rid the college of a president who was evil, venal, and quite possibly deranged. I remember many honest people who were difficult and many more who were congenial but dishonest: I came to lose a considerable amount of respect for a plurality of my colleagues: not only jellyfish—too many sit-down guys and girls, the sort who would have joined the French Resistance in April of ’45—but counter-intuitively narrow-minded outside their fields, especially politically: they would abandon method and reason only to become the bigots they deride. I became cranky and perhaps I allow that to coarsen my memory, as life tends to coarsen certain aspects of any sensibility. So little was at stake, as Henry Kissinger has acutely said of business at the Harvard faculty senate.

On the other hand, I had the joys of teaching: I mean the act—the transformative action itself—in all its venues, as well as most of my students (some twenty thousand, counting those in the mass lecture that I delivered, twice a week, for twenty years). Can anything compare with owning the classroom, the seminar table, or the lecture hall? With knowing your stuff and how to handle it? With all the adjustments one must make, often on the fly, as you read your students? I’ve done some boxing: “ring generalship” is not very different from classroom management. (Except for the being hit part—and even there were some close calls.) With preparing a new class, re-formulating an old one, or preparing and introducing a whole new curriculum? Students, of course, come in all styles, and although the student-teacher interaction could be a challenge, even alarmingly so, it was rarely dull—

—except for the grading process, about which I do not intend any systematic discussion: it was no fun. One semester I decided to get rid of that funlessness. In order to address the pressure that comes from “going for the grade,” for one special seminar I hand-picked (so to speak) six students: the reading would be tough, conversation a requirement, and everyone would be guaranteed an A from the beginning. No questions. All went well—until the final essay was due. Not one of these fine, specially invited students— all of whom had visited my home as a class, for dinner—submitted a paper. Lesson learned.

With all their innate inabilities, lack of maturity, skewed expectations, and pot-holed preparation, students abide over and especially within the semesters. And the good a professor who goes all in with them can do—including good spread over thousands of hours outside the classroom—is literally its own reward. I’ve rarely been more myself than when I’ve been among students, in or out of the teaching theatre, and few feelings compare with the one stirred by a student, perhaps from many years earlier, thanking me.

It happened that my father died suddenly while I was away in Oxford on sabbatical in 1974 researching my doctoral dissertation on C. S. Lewis. Besides normal parental monitoring (very discrete), my father never questioned or in any way intruded upon my decisions respecting education or choice of profession. He simply was not a factor. That was not the case, however, with his death: my internal landscape changed so dramatically and pervasively that for a while even my teaching changed (though without my knowing it), and not for the better. Withal, teaching remained an exciting performing art, with all the gratifications “thereunto appertaining,” as most diplomas say. Alas, the real toll is taken by the encumbrances that attach to teaching—clerical hindrances, administrative uncertainties, meetings, committee chairmanships, collegial pettiness and assumed privileges, logistical debilities.

An interesting question here is this: What role, if any, does religious conviction play in teaching? Teaching, a performing art and a rhetorical one at that, means the answer depends upon your audience, that is, on one’s students. Mine have been preponderantly religious, mostly Christians formed in the Black church (though very few Catholics), but also Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs and others. And what these students know is that their professors are commonly downright hostile to religion.

But effective teaching requires authenticity. Over the years it became evident to students that, unlike most of their professors, I was not shy about my belief. Never any proselytizing, of course, no disrespect of any kind for any religion, but implicit belief in a divine creator. Rarely did any such expression arise in class, though as a teacher of words I would often quote the opening verses of St. John’s Gospel in the first week, which I would explore philosophically: our business, after all, was the Logos. Out of class students would sometimes approach me to express their appreciation. For example, Muslim students twice invited me to break Ramadan fast with them.

When discussing political rhetoric I would plainly declare that I did not favor Obama’s or King’s but do strongly prefer Malcolm X’s and Frederick Douglass’s. Once, when demonstrating an argument, I allowed that the holiday celebrating our African American heritage should not be Martin Luther King Day but Frederic Douglass and Sojourner Truth Day, both of whom, after all, had been slaves, not entitled, richly-educated scions of the middle class. A local reverend who ludicrously called King a ‘saint’ complained to the administration—which, to its credit, did nothing: I heard of the incident long after the fact. When during any discussion an opinion was appropriate mine might reflect a religious belief or, more likely, invite a religious reference. An authentic, non-intrusive baseline of identity will, in the long run, pay dividends.

Read more in New English Review:

• Ronald from the Library

• Real People

• Skewed Projection in a Broken Mirror

Quijote reigns supreme.

Compulsion, Meyer Levin’s riveting account of the infamous Loeb-Leopold/Bobby Franks abduction, murder and trial. How Clarence Darrow saved them from execution seemed miraculous: with a mind sharper than a scalpel and words and tactics to match, the man did the impossible. (Later I would learn much more about Leopold from his superb Life Plus Ninety-Nine Years: by all standards, he was reformed.) An English teacher, Mr. Balish, who saw me reading the book, recommended the riveting An American Tragedy. Thereafter came The Great Mouthpiece, about William Fallon (a gifted scoundrel), Final Verdict, about Earl Rogers (who many believe to have been the greatest trial lawyer in our history), My Life in Court, by and about Louis Nizer, and my all-time favorite, Courtroom, about the great Samuel Leibowitz.

[1]

.

«Previous Article Home Page Next Article»

__________________________________

James Como is the author, most recently, of The Tongue is Also a Fire: Essays on Conversation, Rhetoric and the Transmission of Culture . . . and on C. S. Lewis (New English Review Press, 2015). His forthcoming book, from the Oxford University Press, is C.S. Lewis: A Very Short Introduction.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast