Free Stuff & Three More

By Elizabeth Crowell (February 2023)

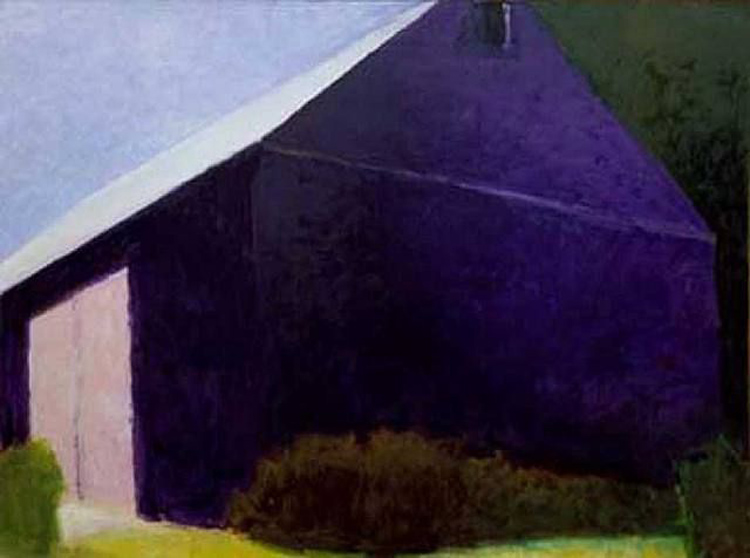

Deep Purple Barn, Wolf Kahn, 2003

Free Stuff

In hasty letters, a sign, “Free Stuff.”

is wedged among boxes of orange plates,

a baby pram with fluted feet, a stack of almanacs,

transistor radios, yellow chairs.

We are in need of a kitchen table, see one,

free, gleaming, one drawer with a glass knob

that catches the October sun’s loose shoots.

We pull ourselves out of the car to look,

but the table’s body has a crack,

which we massage for quite some time,

moving our fingers along the splintered vein,

as if we are reading someone else’s loss.

We came to the red barn,

dusty windows, urns of fat with spinning donuts,

the hill, tipping with apples,

the sign for the place painted apple-red.

We fill our bags beyond what we will eat,

promise ourselves breads and pies and sauce

we will not make; there isn’t time.

And on the way back, late day,

two women who could be us

are picking up two blue tablecloths

from the pile of junk, whipping them in the dusty air,

like toreadors, warding off a snorting beast.

My Father Mourns his Father, Dead since 1960

After a meal of bacon and eggs

my father says he feels sorry that his father didn’t get

a bit of money from the family company

because he died too young.

He worked so hard and lost his job

in the Great Depression, and the family company

went almost broke, and then bounced back,

and then he had that heart attack,

and left my grandmother neatly set up

with trips to Bermuda and ladies’ lunch.

My grandmother reported that my grandfather

was such a gentleman, and went farther

once in a while to say he wept openly

at the Pathetique Symphony.

I point out now he did all right,

private schools, four sons, all bright

a house with two tiers of gardens, a goldfish pond,

and as I go on, my father frowns,

and says again, he doesn’t want to bury my mother

where she said she wanted, with her father, and mother

in that lousy graveyard in Orange, New Jersey,

along with the aunt who killed herself, and the dead baby.

I suggest again the Cape, where my mother and father

would walk down the sandy and eroding reach

until they were almost out of view, windbreaker puckering,

in the photo that someone else took of them.

That’s better, he agreed, Nauset Beach, perhaps,

his own father sprinkled on the igneous rock of

Watchung Mountain, where I walked as a child,

never knowing he was there.

Deer Lake

A sky was in the lake at dusk,

the red oaks heavy on the shore,

My parents sat at the picnic table

limp and silent; the mosquito candle

lit up the blood on the hamburger plate.

Later, my father backed out the wagon.

the headlights in the woods.

The deer were only occasional,

their light-footed bodies flexing

Years later, they were gone

but bears came down from the mountain,

where they had multiplied,

lumbered through the picnic grounds,

so many that the last time I was there,

bear horns hanging from the trees, like fruit.

Persephone, Back for a Visit

You never saw the chariot until

I was on it, its fire full of my screaming.

The flowers were still in my hands, fading.

There was the moment I was leaving,

like the shift of cloud over a body,

a moment when it could be momentary.

Never mind the way I was drifting

on the earth when it drifted open.

Never mind I wasn’t paying attention.

There were even witnesses,

demi-gods and the flowers that you mend,

and they could not do a thing for me.

As for the seed, the pulp of which still sticks

in my teeth, the way the juice ran down,

the quick last kiss I gave him,

What have you ever given me

that I can’t get somewhere else?

Table of Contents

Elizabeth Crowell’s work has been featured in Another Chicago Magazine, Baseball Bard, Atlanta Review, and Bellevue Literary Review (where it has twice won the non-fiction prize) and more, and was recently nominated for a Pushcart Prize for a poem published in Tipton Poetry Review.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast