by Geoffrey Clarfield (July 2023)

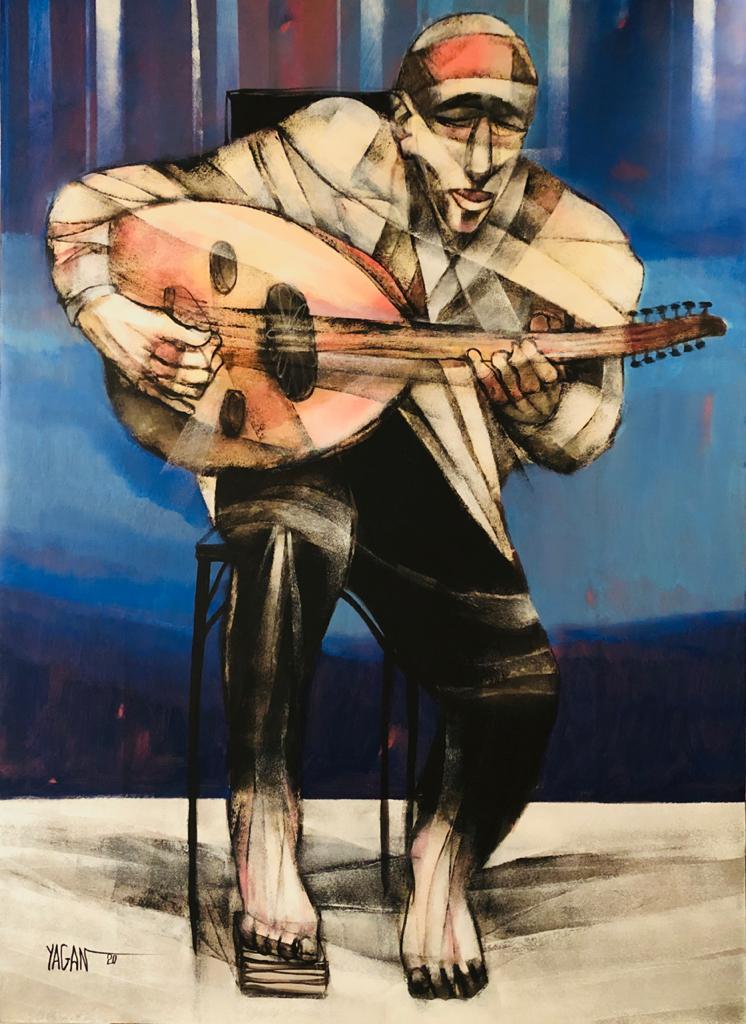

The Oud Player, Saad Yagan

I am sitting in my courtyard in Tangier, and I am playing my oud. It feels like a light, oval watermelon that snuggles under my right shoulder. It does not need a strap. I navigate the neck board with my left hand, like a guitar, and pluck the strings with an eagle’s feather (when I can get one) or a plastic equivalent.

The oud has no frets and so it is like a guitarist playing a violin. It looks deceptively simple, but it is not. Every note must be correct and there is an unmistakable feeling in the left hand which you must master to give the sonic results acceptable to an Arab or Moroccan Jewish audience.

Otherwise, it sounds like a dead, one dimensional use of the instrument that can be heard in so many reconstructed medieval music ensembles that lose the sweep of each note and an instrument that adheres to an ancient soundscape so different from the European tempered scale. Playing the oud “like a native,” is all about flow. Either you have it, or you do not.

I am not an oud virtuoso but, I play with that feel and I have been accepted by both audiences and musicians back home in Israel, in Turkey and now here in Morocco where I spend a little too much of my time each week at the Conservatory of Tangier painfully and patiently learning songs and melodies that are probably more than a thousand years old, kept alive in oral tradition only.

If the guitar has become “the” instrument of lyrical expression in Europe and the Americas, the oud, or pear-shaped lute of the Arabs and Turks is the “guitar” of the middle east and north Africa.

The oud comes in many shapes and sizes, the Arab ones are usually larger, and the Turkish ones are smaller. They are tuned differently in different parts of the Arab and Turkic world.

The oud is used in popular music, but it is also used in what has become known as “classical music.” In Morocco this means long musical poetic suites called “Nawba” and which according to the latest ethnomusicological research, were developed by Arabs and Jews at the medieval courts of the Muslim Emirs of Spain.

Miraculously in 1492 when King Ferdinand and Isabella expelled first the Jews of Spain and then the Muslims from Spain, the music of the three great centers of Nawba or as the Arabs call it “The music of Andalous,” having originated in 9th century Cordoba, was relocated in different cities in North Africa where three variant traditions emerged. Today, one of the most famous Moroccan Jewish interpreters of this tradition is Benjamin Bouzaglo.

There is a more popular, less closed specifically Moroccan repertoire of oud inspired song called Al Mlhoun, with musically expressed poetry composed in Morocco during the last three centuries. It is a form of popular but literary extension of the suites.

This kind of musical creativity and divergence has been going on for a long time as we can see from the philosopher Al Kindi’s 9th century detailed description of the oud:

…length [of the ‛ūd] will be: thirty-six joint fingers—with good thick fingers—and the total will amount to three ashbār. And its width: fifteen fingers. And its depth seven and a half fingers. And the measurement of the width of the bridge with the remainder behind: six fingers. Remains the length of the strings: thirty fingers and on these strings take place the division and the partition, because it is the sounding [or “the speaking”] length. This is why the width must be [of] fifteen fingers as it is the half of this length. Similarly for the depth, seven fingers and a half and this is the half of the width and the quarter of the length [of the strings]. And the neck must be one third of the length [of the speaking strings] and it is: ten fingers. Remains the vibrating body: twenty fingers. And that the back (soundbox) be well rounded and its “thinning” (kharţ) [must be done] towards the neck, as if it had been a round body drawn with a compass which was cut in two in order to extract two ‛ūds.

Every week I walk from my house in the old city or medina to the conservatory which is in the old city.

The minute I leave the confines of my house with its enclosed courtyard, Moorish fountain and orange trees, I am assaulted by the visual, aural and nasal, cacophony of the Moorish Street. I pass by the many vendors of fruits and vegetables with their stalls open to the street, all yelling out their latest and best prices, pass donkeys laden with produce from the countryside, thwacked by Berber women with unbearably beautiful wide brimmed straw hats with black brocade.

I inhale the smells of a local spice seller, the pungent smell of hanging meat outside the butchery, mixed with the exhaust of mopeds and motorcycles that invade the old streets, the verbal assaults of hustlers trying to be my tour guide (“I show you all the sights and introduce you to local women”) and young, aggressive twelve year old beggars asking for money yelling, like soccer fans, “Flus flus flus,” the Moroccan dialect word for money.

Then there is the stunningly blue sky and what 19th century painters like Delacroix called Mediterranean light, not to mention men in hooded cloaks, women in black body covers with only their eyes peering out, young women in revealing French outfits and young men in leather jackets, looking like swaggering fifties style Americans, “rebels without a cause” but in this case their cause is 25% per cent youth underemployment. The Moroccan Street is an assault on the senses and unless you like that kind of thing, this is not the country for you.

I then spend an afternoon sitting with much younger students (some of them blind, for this will guarantee them a living singing and playing at weddings and other ceremonies of the life cycle here), committing the tunes and the songs to memory through repetition. One of them by the name of Abdellatif is a boy of about 12 who sits beside me.

This is a preindustrial way of learning similar to the Quranic schools of the Muslims and the Talmud Torah of my Jewish ancestors here. It slows down my life.

I have been taken under the wing of Haj Jamil, the head of the Conservatory. He is in his late seventies, a master of the Andalucian suites and a gifted interpreter of Mlhoun who, when he is in a light mood can also knock off the super-fast songs of northern Morocco like Laila Fatima. He is a devout Muslim and an exhibitionist on stage. Quite the character.

He is very nostalgic about the former Jews of Tangier so many of whom played with him in his youth in the traditional orchestras of Tangier. He sees in me some sort of continuity after the rupture and scrupulously avoids any talk about politics or economics, national or regional.

In the middle of each afternoon session, we take a tea break. I always bring some fresh bread from the local bakery, some cheese, some olives and olive oil and there make and eat my sandwich in the open courtyard of this rather old and rambling house, watching the pigeons fly near the roof of this two storied, multi roomed old Moroccan mansion.

One day I returned to the performance area after my snack where I had left my oud and it was gone. The stand was there but the oud was not. I thought perhaps someone had borrowed it without telling me. I mentioned this to Haj Jamil. He looked around and asked around. No one had seen anything. We searched the house and found nothing. I had to call Hamid.

Hamid is the Moroccan who works for the local police and the security services to make sure that as Israeli Cultural Attaché to the Kingdom of Morocco, nothing untoward will happen to me. He came to the Conservatory and interviewed everyone there. He could not figure out what had happened.

Everyone was worried as they did not want the local press to get hold of the story. Hamid told me that the last thing he wanted to see was a headline, “Israeli Cultural Attaché Has Oud Stolen from Conservatory in Tangier.” He confided that with high youth underemployment, petty theft kept the tourist police far busier than they wanted to be and took away key personnel from the fight against narco traffickers which is the concern of the Tangier area security institutions.

I asked Hamid and Haj Jamil to say nothing and ask the students not to discuss it with their families when they went home. I walked home without my oud. The beggars almost to a man asked me on my return walk, “Ya Sidi, fayn al oud dyalek”” Where is your oud? I could not answer them.

I got home and I was subdued. Had someone really stolen my oud? Was this a political act? Was it done to “teach me a lesson”? But what lesson and from whom, the left, the right, the fundamentalists? It did not make sense.

Hassan my gofer had just come in from his shopping and Zainab started chopping vegetables in the courtyard for the evening meal. I told the story to Hassan, and it was clear that he was perplexed. His face took on a dark visage as if someone had offended him personally, “Your oud?” he said both as a question and a statement. “There is no honor in this!”

Then surprisingly he told me, “It is not that difficult to locate a stolen or misplaced item. We have ways to do this here. But first I must light my sebsi (marijuana pipe).”

It is hard to believe but those Moroccans who grew up without alcoholic beverages often smoke kif (local marijuana) to solve problems. Hassan told me, almost like Sherlock Holmes, “Sidi, I think this is three pipe problem.”

He then retreated to a corner in the courtyard, set up a pillow and lit his pipe. His eyes stayed focused on the pigeons going on and off the roof like an Escher print. He was lost in space for a good three hours. Hamid my security friend, had spent time fighting drug smugglers and he fears that Morocco may lose the tourist trade and end up like Mexico, a kingdom run by drug lords, but that has not yet come to pass (Insha’Allah).

Hamid has explained to me that the old-fashioned way of smoking kif is traditional and calms men down. It does not stir them up. I think that in this context it helps people with little book learning to think outside of the box, engage in lateral thinking to solve personal and social problems for that comprises most of Moroccan life for everything is personal.

Only a few well-educated Moroccans like Hamid and his wife think sociologically and statistically. That is why the average Moroccan believes in various conspiracies because she or he is probably in on one at the local level, and they project that experience up the social ladder. They may not be wrong for Morocco is a network of networks, hierarchical, changing and at a deep level staying the same. Many actors, few spoils.

Just before I retired to my bedroom on the second floor Hassan came to me and said, “I am going to see the Fqih, and I will back tomorrow. Do not worry about your oud.” He then closed the door of our compound and disappeared into the dark alleys on a moon less night.

If you ask a Moroccan Muslim “What is a fqi?” This is what he or she may say: A fqi is a man who has memorized the Koran. He also teaches it to boys and young men in an Islamic school. But he is more than that. Some Fqi have blessing or baraka and their mere presence can change things for the better. They also write talisman that can protect you from witchcraft, the evil eye and the demons of the night (the Jinn). And they have other powers…

So, there you have it, a learned man who at the same time uses religion as if it was magic. It is almost as if underneath the veneer of the five pillars of Islam in Morocco, there is another religion which includes a lot of magic that informs the daily life of most Moroccans.

England was like this just before the Reformation. I learnt this at a seminar at Oxford University. It was given by historian Keith Thomas where he gave us lectures from his book Religion and the Decline of Magic. Using sources from pre-reformation times he more or less proved that most congregants in England treated the sacraments of the Catholic church as forms of magic; to cure disease, to prevent misfortune, to attain desired ends. The whole dichotomy between magic and religion was in reality a continuum. So, it seems to still be the case in Morocco today.

The next day I was expected in the office after lunch, so I had a leisurely morning and Hassan told me he had something to tell me. Zainab made us tea; we sat in the courtyard, and said, “Last night I went to see the Fqi, Abdel Malek bin Muhammad. He is a follower of the Saint Mohamed al-Hadi ben Issa who is also known as the perfect Sufi master or as we say in Arabic the Shaykh al Kamil. He lived here around five hundred years ago and has many followers of his Sufi path in Morocco today.”

Hassan continued to talk.

“We went up to the balcony of his house. There he built a small fire. He asked me to look into the flames. He took out his rhaita (a double reed oboe). His son Lahsan played the frame drum, the bendir. They began to play one of the melodies that the Aissawa, the followers of the founder of the Aissawa play at their ritual gatherings or hadra, and they told me not to move my eyes.

“I found it very difficult until a point where the music took over me and I began to thrash about. I lost consciousness and I suppose I was transported to the realm of the King of the Jnuun. He was feasting and Lahsan and is father were playing in front of his throne. I found myself seated beneath him on a big Berber rug. He came down from his throne and showed me a triangular tattoo on his arm. He yelled at me, “Look at it and if you look away you will instantly be transported to hell for, I am the eye of the fire and the ruler over the world of spirits. I am Allah’s appointed viceroy who was given power over darkness at the creation.

“Slowly the triangle turned into a mirror and then into a clear pane of glass. I found my self floating above the courtyard of the conservatory. I could see you playing. I could see you get up and then, I saw a young man, he must have been blind, for he was wearing dark sunglasses. I saw him take your oud, put it in a case and walk out the door using his white cane to guide him with his other hand. He then took your oud home. ”

The master of the Jnuun yelled at me, “Go find it or stay here with me forever!”

I woke up in a sweat. My clothes were completely soaked. I told everything that I had seen to the Shaykh. He said, “That is good” Now give me fifty dirhams and go home.”

The two of us took a taxi to Abdellatif’s house. His father let us in and made us tea. He called Abdellatif into the main room. We politely asked him to bring his oud and play for us. He brought out my oud and played a marvelous section of an Andalucian suite, as good as his teachers.

We asked him what he had done the day my oud disappeared, and he told us that he had walked over to the tea area and had has his snack. When he returned to pick up his oud it felt different, and the voice was sweeter. He was delighted and came home to tell his parents who sat in rapture at the sound of this marvelous instrument.

When I explained to all assembled what had happened Abdellatif apologized profusely. He was embarrassed and ashamed. We now realized that Abdullatif’s oud was the one that had been stolen. We reassured him that no offense had been taken and Hassan and I returned to the Conservatory. I would borrow an oud from the Haj and do what I could do find Abdelattif’s oud

Hamid was waiting for us at the Conservator. We told him the whole story. He said, “In all my years of police work I have never heard anything quite like this.” He was so agitated that his face turned as the British put it ‘a whiter shade of pale.’

The three of us were now committed to get Abdellatif’s oud back to him. Hassan looked at me stoically and said, “Sidi, this is now a four-pipe problem. Let me go home and think about what it is that we all must do.”

Afterword

As a teenager I read the entire works of Sherlock Holmes with gusto.

I often noticed that when perturbed by an inability to solve a crime he would retreat to his studio and announce to Watson that “this is a three” or a “four pipe problem.” He would then smoke his pipe until he gained the insight, the lateral thinking and logical deduction that defined his character in the pursuit of criminality.

I sincerely doubted that Hassan had ever heard of Sherlock Holmes. And so I explained all of this to him. He laughed and told me, “During the forties we got films from England which were dubbed into French. I would sneak into the theatre and watch them. It was there that I saw my first Sherlock Holmes films in black and white starring Basil Rathbone. That is where I discovered that he and I smoked from the same pipe.

Table of Contents

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

I’m never quite sure where I am in your stories, as they haze reality a bit I think. But they are enjoyable. I think I am learning things.