by Norman Berdichevsky (September 2017)

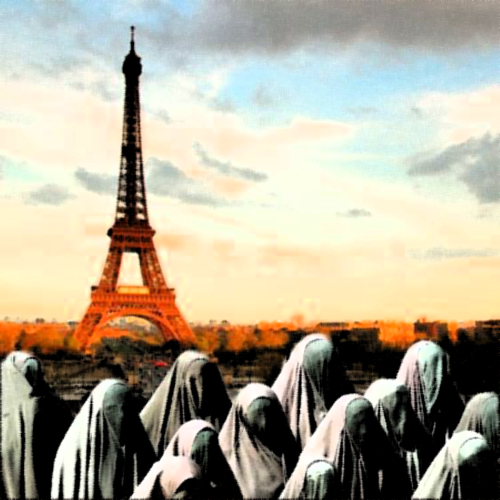

Few books in the last decade have aroused the amount of controversy and public debate—at least in Europe—as has Michel Houellebecq’s Submission, the fictional tale (though all too real) of a submissive intellectual class willing to trade more than a thousand years of Christian and national patriotic traditions of the nation-state, as well as fundamental values of Western civilization (including the right to an education free from religious dogma and equality of the sexes), for an Islamist regime in partnership with the traditional “socialist parties” of Europe. This apparently contradictory scenario (by American standards) is now all too real in much of Europe, a fact driven home by the remarkable coincidence of the book’s publication on the very same day as the Charlie Hebdo massacres in Paris.

Once in power, the new regime (dominated by the same Muslim Brotherhood which former President Obama favored until it was overthrown by massive demonstrations in Egypt) introduces, with socialist agreement, obligations upon women to wear the veil in public, withdraw from public life, accept polygymy and end any openly secular public education or teaching by non-Muslims.

I happened to finish reading the book in a few sittings just a few days after watching two films that left me with a profound unease about Diaspora Jewish “idealists” and “patriots,” who acted so as to justify Lenin’s dictum, “Capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them.”

These two very recent films deal with the assassinations of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand (that provoked the First World War in 1914), and of Leon Trotsky in Mexico in 1940. Both films dwell at length on two ostensibly “minor” Jewish characters. In reality, both of these characters played major roles in the events which, almost certainly, would have taken a very different course and altered world history, had they been anything but Jewish.

These are the conclusions that viewers are left to ponder, and they speak volumes about the nature of existence for highly educated, sensitive, ethical and politically “liberal” individual Jews today in the Jewish Diaspora who are/were hostile to, apathetic or simply ignorant about, the reality of Zionism then or of Israel today.

The films are “The Chosen” (El Elegido), 2016, written and directed by Antonio Chavarrias and produced on site in Mexico, and “Sarajevo” (Das Attentat), an historical drama by Austrian director Andreas Prochaska, starring Florian Teichtmeister and Edin Hasanovic. “Sarajevo” was produced in 2014 by both German and Austrian television to coincide with the one hundredth anniversary of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and the outbreak of World War I.

“Sarajevo” focusses on the character of Leo Pfeffer, the examining magistrate appointed to handle the investigation of the assassination. Pfeffer is outraged at the apparent gross incompetence of the local authorities in not preparing adequate security measures for the Archduke’s visit to Sarajevo. Leo is a brilliant, highly motivated, and competent investigator but he must tread carefully; he is Jewish and any failure to satisfy the higher authorities in Vienna will cost him dearly, probably ending his career.

He knows that he is under a deadline to complete his investigation and find the culprits among the Serbian government and ultra-nationalist Serbian or Pan-Slavic organizations that provided moral, financial, material, and technical support from Belgrade to the perpetrators.

His situation is made all the more tenuous by a love affair with Marija Jeftanovic, the married daughter of a wealthy and prominent local ethnic-Serbian land owner in Bosnia, who prospered through the sale of agricultural products. Pfeffer is a Hungarian-Croatian Jew and who, as so many others had done, converted to Christianity to further his career. He is generally regarded with suspicion, scorn or contempt by many of those in the army and civilian administration in Austrian occupied Bosnia-Herzegovina with its substantial Muslim population. Marija’s situation as a married woman and a suffragist only make Pfeffer’s situation more precarious due to what is regarded as his flouting of traditional morality.

His knowledge of the Serbian language should be an advantage of course, and it is one of the reasons he was appointed; but it also links him with the perpetrators of the crime. His perfect knowledge of correct German only adds to the view that he, like so many other multi-lingual and cosmopolitan Jews, cannot be trusted. In a conversation with Marija’s father, Pfeffer begins speaking in German but the father prefers Serbian which Pfeffer can easily understand from his Croatian background.

When admonished to speak “our language”, the two men disagree about what is meant by “our language” and “our country.” Pfeffer vainly tries to reassure the elder Jeftanovic that “one’s country” is “wherever one does well.”

This is the same dilemma faced by Albert Einstein and highlighted in the National Geographic TV special “Genius.” Einstein, like Pfeffer, was under pressure not to give prominence to the work done by Maleva, his Serbian wife. This was also his own attitude and that of his Jewish family members who feared for their position as the “favored” minority compared to the Slavic peoples under domination in both Austria and Germany.

While extremely talented German-speaking assimilationist-oriented Jews could be “tolerated” and exploited by the state (and the ultra-orthodox religious, who could simply be ignored), the Slavs were suspected of ultimately conspiring to end the domination of the Germans and endanger the empire.

Prior to watching this film, all but the most dedicated historians would have been unaware of the character or motives of the investigating magistrate whose conclusions laid buried in the archives for decades. Leo Pfeffer is not, however, a “minor character.” He is central to the ultimate official report which must condemn Serbian nationalists operating in Belgrade at the instruction of the Serbian government.

Pfeffer is forced to bow to pressure against his conscience and resist the advice of a close Austrian doctor friend, who advises him simply to swallow his conscience and, that no matter what he decides to do, his Jewishness will always be held against him. This is the reason that he jocularly addresses Leo as “Moishe”.

The local police force in charge of the security arrangements numbered only a hundred and twenty policemen placed along the route that the royal party was scheduled (announced in advance) to follow the military authorities kept 70,000 Austro-Hungarian soldiers then in Sarajevo in their barracks. The very day of the visit by the Archduke and Duchess was Vidounan, a Serbian day of mourning that commemorated the day Serbnian loss of the historic battle of Amselfelde in 1358 which lead to five centuries of Turkish/Muslim rule. A visit by the heir apparent to the Hapsburg throne was therefore widely regarded as akin to rubbing salt into their wounds.

Piecing the evidence together from what is now known through historical research, the assassins were motivated to carry out their act by a conspiracy of the “Black Hand” Serbian underground movement without the full knowledge or cooperation of the Serbian government. At the last moment, the government withdrew any provisional support to the plotters in a last minute attempt to prevent them from leaving Serbia to make their way to Sarajevo.

Pfeffer quickly becomes aware of the Austrian military authorities’ interest to prevent any evidence implicating them in a plot to get rid of the notoriously “liberal” heir to the throne who had spoken of uniting the Slavs within the empire to expand it into a “Triple Monarchy.” Germany reassures Austria that if Russia or France threaten to come to Serbia’s defense, it will intervene on Austria’s behalf.

On July 13, 1914, an official much higher than Pfeffer, Friedrich von Wiesner, from the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Office uses some of Pfeffer’s preliminary material and reports back to Foreign Minister Leopold von Berchtold that “there is nothing to prove or even suppose that the Serbian government is accessory to the inducement for the crime, its preparation, or the furnishing of weapons. On the contrary, there are reasons to believe that this is altogether out of the question.” The only evidence that could be found, it seemed, was that Princip and his cohorts had been aided by individuals with ties to the government, most likely members of a shadowy organization within the army, the Black Hand.

Pfeffer and his final dissenting report become lost footnotes published long after the hostilities had already killed hundreds of thousands of men. The Archduke was ironically the one man in the Austrian Empire committed to averting war with either Serbia or Russia. He was on record declaring, “I shall never lead a war against Russia. I shall make sacrifices to avoid it. A war between Austria and Russia would end either with the overthrow of the Romanovs or the overthrow of the Hapsburgs or perhaps the overthrow of both!” Of course, he was right on both accounts.

In “The Chosen,” Sylvia Agaloff (played by Hannah Murray) is a devoted Brooklyn Jewish communist and social worker who arrives in Mexico to work for her devoted idol, Leon Trotsky. Once there, she is exploited by Ramón Mercader, a dedicated Soviet agent trained by his fanatic communist mother, Caridad, in Spain, to make any sacrifice (including his life), in service Stalin. He is taught to ignore every human emotion of compassion and decency. Mercader’s dedication is demonstrated by willingly killing his favorite pet dog on command from the NKVD.

NKVD agent Leonid Eitingon, who operated in Spain under the alias of General Kotov, had a long running love affair with Ramon’s mother. He trained Mercader in Moscow in 1937 in the ways of espionage and guerrilla warfare and was the brains behind the assassination.

He chose Sylvia and correctly believed that she would be attending a secret conference of Trotsky’s Fourth International (about which the NKVD had been tipped off) in France in the summer of 1938. The NKVD used a wavering Trotskyite and acquaintance of Ageloff, to travel to Europe with Ageloff and set her up with Mercader via another agent. Mercader swept her off her feet as the debonair, wealthy and handsome Trotskyite sympathizer who followed her to Mexico where she had become a close associate of the victim.

Several crude attempts to assassinate Trotsky including a machine gun attack on the compound are foiled by the Mexican police but the NKVD agents have prepared Mercader for years to use every means available to achieve their goal; the easiest route to gain access to Trotsky is by stealth and deception of his innermost circle.

The most naïve and easily-fooled woman in the compound where Trotsky is now virtually a prisoner, gives Mercader access. Like Pfeffer, she is not a minor character. She provides the key through her infatuation and misplaced Jewish idealism and is able to overcome the suspicions of Trotsky’s closest comrades. Out of a sense of pity, they grant her the favor of being with her lover inside the compound on special occasions.

The film also explains the use of an ice pick as a weapon. Any firearm would have immediately aroused suspicion. Only a “household item” already present in the kitchen and able to be hidden in a fold of clothing provided the ideal unsuspected weapon.

Both of these films are high drama, full of suspense but they are also a valuable guide to the workings of two bureaucracies—one, the last gasps of a 19th century empire on its last legs, and the other the ultimate Soviet debasement of their perverse ideals.

Pfeffer knew that the Serbian conspirators were totally lacking in the skills necessary to acquire the weapons and devise a plan that would succeed. Indeed, their “success” is due only to blind luck and the stubborn pig-headedness of the local police. By contrast, the NKVD undertook the monumental efforts required to ensure that every detail of their agent’s cover story and psychological/sexual and romantic charm for Sylvia were complete.

His cover as a wealthy, dapper, charming Belgian businessman with sympathies for the Revolution and Stalinist regime were readily believed by Sylvia in spite of some initial reserve about the newcomer. Nevertheless, sympathy for Sylvia’s chance at a love relationship overcomes their logic. She is not particularly attractive, and Trotsky and his camp guards developed a special fondness for her.

Her repayment is the cruelest blow any jilted woman has faced: BETRAYAL—not for another woman, but for Stalin! She unwittingly becomes an accomplice to the murder of her beloved Trotsky, leader of the idealistic cause to which she was devoted. The crime takes on the character of a double murder.

Would events have transpired differently if Sylvia and Pfeffer had not been Jewish? This is a matter of conjecture but the list of misplaced Jewish idealism for remote non-Jewish causes, leaders, and nations is a very long one.

My reaction is born of the eleven years I spent in Israel and the realization that Zionism is the one ideal that succeeded due to the incredible devotion and sacrifice of four generations of Jewish heroes and leaders that justified the devotion of their followers.

Reading Submission, one is struck by memories of the Vichy regime and the fate of the Jews, notably the many Diaspora idealists who rejected Zionism as too provincial, and believed that their fate was inevitably tied with the success of some grand universalist ideology such as Communism, or believed that their fate depended on complete identification with the culture and national ideals of their adopted homelands.

The book’s main protagonist, Francois, is a university professor, a nominal Catholic, but actually, a typical agnostic academic and opportunist obsessed with his favorite pastimes writing, food, wine, tobacco and sex. He receives a letter from his former (much younger) Jewish girlfriend, Myriam, who has reluctantly followed her parents to Israel. She complains that she doesn’t speak a word of Hebrew and that she loves French cheese! Her parents, well aware of what happened in Vichy and the dangers they cannot prevent, make the decision for starting a new life in Israel.

Myriam has repeatedly told Francois that she is devastated because she feels so thoroughly French and has always been devoted to France and French culture but, after six months, she writes to him that she is entranced by the vibrancy of Israel and its people who live life to the fullest and are unafraid of the myriad dangers surrounding them. This only increases his anguish and pessimism over what he faces in an Islamist France. Francois feels the loss of his country and way of life all the more intensely because, as he reluctantly answers her . . . “There is no Israel for me.”

Later, he convinces himself that he can nevertheless live a more comfortable life if he simply goes with the flow and reaches the convenient choice that what he gains is much more important at his stage of life than what he could lose by resisting.

To many of their contemporaries, fellow comrades and superiors, Leo was one of many “Moishes” in the Diaspora of the last two thousand years: competent and skilled, but unable or unwilling to take final responsibility for a decision that could only have been taken at the highest level by someone from the majority population and ruling class like Friedrich von Wiesner. Sylvia, as devoted a follower as many Jews were in universal causes was regarded with pity, ending in a catastrophic mistake. Did their Jewish identity plague them?

What we know for sure is that Pfeffer followed a time-honored strategy of many assimilationist-oriented Jews in Europe who converted to Christianity to protect or forward their careers. Sylvia, who came from a predominantly Jewish environment in Brooklyn, blindly ignored her background in an attempt to identify with what she considered a much larger cause that would benefit all of humanity. In so doing, both of them tried the patience and “tolerance” of their comrades or superiors who either doubted their effectiveness (Pfeffer) or made costly allowances for it (Agaloff).

Myriam, pushed by her parents, took the plunge and came to realize where she belonged without apology. She avoided the dilemmas, the contempt or pity that would have been her lot by remaining in a Muslim majority France. She made the right choice, leaving Francois behind to envy her sense of fulfillment in Israel.

____________________________

Norman Berdichevsky is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting and informative articles, please click here.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by Norman Berdichevsky, click here.

Norman Berdichevsky contributes regularly to The Iconoclast, our Blog. Click here to see all his contributions on which comments are welcome.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link