By Guido Mina di Sospiro (December 2018)

Shomer Shabbos Variant, Todd Slater

In Reflections on the Death of Mishima, Henry Miller, after singing the praises of both the Japanese author who put an end to his life with a ritual suicide by seppuku (abdomen-cutting) and nipponica in general, noticed: “His utter seriousness, it seems to me, stood in Mishima’s way.” In itself, the observation sounds like a joke. Mihisma, dead serious (indeed!) about everything, would have disapproved vehemently. Humor has been frowned upon for centuries, in fact millennia, in our own western tradition, too.

Plato censored the enjoyment of comedy in Philebus as a form of scorn. “Taken generally,” he wrote, “the ridiculous is a certain kind of evil, specifically a vice.” In Rhetoric, Aristotle stated that wit was educated insolence, while in the Nicomachean Ethics he admonished: “Most people enjoy amusement and jesting more than they should . . . a jest is a kind of mockery, and lawgivers forbid some kinds of mockery—perhaps they ought to have forbidden some kinds of jesting.”

Needless to say, early Christian thinkers objected to humor and laughter, too, a trend that continued through the Middle Ages. Later, the Puritans typically encouraged the faithful to live sober, serious lives, while Hobbes and Descartes chimed in with their own strictures. In 1900 the French philosopher Henry Bergson published Laughter, a collection of three essays that, for the first time, concerned itself with the laughter caused by the comic. But Bergson’s effort remains the exception: to this day, tragedy is taken seriously; comedy, is laughed at, both literally and figuratively. When it comes to movies, it remains inconceivable for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to choose a comedy as Best Picture, or as Best Original Screenplay. And yet, making people laugh is infinitely more difficult than making them cry.

Among others, a very perspicacious Asian, a certain Gautama Buddha, noticed centuries ago that “life is suffering,” and listed such an earth-shaking intuition as the first of his noble truths. In fact, the most followed religions on earth, which cumulatively number billions of people—the Abrahamic ones, Hinduism and Buddhism—all have produced their own prescription for diligent life-avoidance. It could be argued that through them the religiosity of life was supplanted by the religiosity of detachment from life. Given such premises, all the more can laughter be seen as a form of cosmic upset. Yes, acknowledges the one who’s laughing, there is suffering, and loss, and sadness, and I laugh, nevertheless. It’s our at once human and superhuman way of saying, Guess what? I’m fully aware of the memento mori, in fact I live with it every day—and I’m still laughing!

Read More in New English Review:

The Divine Maria Callas

What Makes a Poem?

Maryse Condé Substantiates Black Identity with Human Traits

There follow ten American movies as well as three foreign ones that in my view express the best of what humans can achieve when it comes to upsetting the cosmos, and logics with it. Tragedy surrounds us; comedy, not so much. Therefore, let’s find comedy, and laugh. I have made a conscious effort to list movies that are funny throughout, and not just in part, and that are highly rewatchable.

Two notable partially funny movies that do not make this list are Bringing Up Baby, the 1938 classic, because it loses steam after its first two thirds and degenerates into an unfunny farce; and, The Birdcage (1996), the remake of the 1978 Franco-Italian La Cage aux Folles, which is laugh-out-lout funny only in a particular albeit protracted scene, the dinner with the visiting senator and his wife. Also, at least one movie with Laurel and Hardy would make this list, for example, Swiss Miss (1938) minus the operetta outbreaks, if I chose its Italian edition. In fact, many Laurel and Hardy movies were dubbed in Italian by Alberto Sordi, himself a comic of genius, who used for either actor a different pitch and a strong English accent, which contributed very much to their slapstick. In the original, their voices and lines do not add to the hilarity.

In chronological order:

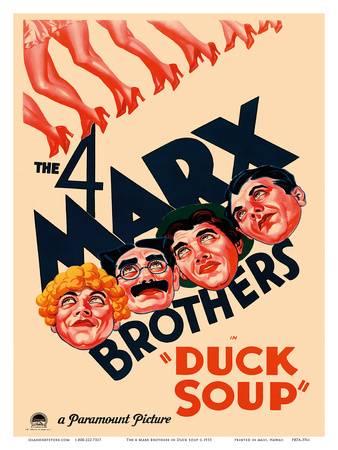

Duck Soup (1933). Uproariously entertaining and perfect in many ways. The adjective “zany”, so often utilized in reference to the Marx Brothers, comes from Zani, the Venetian form of Gianni, “John”, used  in the commedia dell’arte as a stock name for sundry servants acting as clowns. And indeed, each of the funny brothers (Zeppo was cast at first as the straight man, and eventually dumped altogether) could be a mask from the commedia dell’arte: the punny, fast-speaking and ever-deriding Groucho; the pseudo-Italian Chico, or Chiccolini, with his surreal common sense and exaggerated accent; and, best of all, the mute, mischievous, quirky, sabotaging, and ever-horny Harpo. If the characters surrounding the three brothers appear wooden and stilted it’s because they were: the film is, inter multa alia, a spot-on depiction of the diplomatic milieu that, despite its civilized airs and good manners, had not prevented Europe and the world from engaging in WW I just eighteen years before, and would do nothing, seven years on, to prevent the world from plunging into WW II. The pompousness all around is just what the Marx Brothers ever thrived on, quickly establishing themselves as onscreen incarnations of sheer irreverence. The poor Margaret Dumont, unfailingly the butt of Groucho’s jokes, plays Mrs. Gloria Teasdale, a very wealthy widow who underwrites the budget of the Republic of Freedonia. She is as matronly and pompous as it gets, and Groucho gingerly demolishes her every time she opens her mouth. The anarchy inherent in the best of the Marx Brothers’ movies was at the core of the commedia dell’arte, in whose plays many actors would speak, or rather shout, simultaneously, and in which the script was a vehicle for improvising. Duck Soup is a treasure-trove of anarchy, zaniness, irreverence, satire, slapstick—and remains a masterpiece so many years since it was made.

in the commedia dell’arte as a stock name for sundry servants acting as clowns. And indeed, each of the funny brothers (Zeppo was cast at first as the straight man, and eventually dumped altogether) could be a mask from the commedia dell’arte: the punny, fast-speaking and ever-deriding Groucho; the pseudo-Italian Chico, or Chiccolini, with his surreal common sense and exaggerated accent; and, best of all, the mute, mischievous, quirky, sabotaging, and ever-horny Harpo. If the characters surrounding the three brothers appear wooden and stilted it’s because they were: the film is, inter multa alia, a spot-on depiction of the diplomatic milieu that, despite its civilized airs and good manners, had not prevented Europe and the world from engaging in WW I just eighteen years before, and would do nothing, seven years on, to prevent the world from plunging into WW II. The pompousness all around is just what the Marx Brothers ever thrived on, quickly establishing themselves as onscreen incarnations of sheer irreverence. The poor Margaret Dumont, unfailingly the butt of Groucho’s jokes, plays Mrs. Gloria Teasdale, a very wealthy widow who underwrites the budget of the Republic of Freedonia. She is as matronly and pompous as it gets, and Groucho gingerly demolishes her every time she opens her mouth. The anarchy inherent in the best of the Marx Brothers’ movies was at the core of the commedia dell’arte, in whose plays many actors would speak, or rather shout, simultaneously, and in which the script was a vehicle for improvising. Duck Soup is a treasure-trove of anarchy, zaniness, irreverence, satire, slapstick—and remains a masterpiece so many years since it was made.

Of course, there are many funny movies in the following years, not only by the Marx Brothers, but by many others. But as mentioned, I’m intent on making a list of consistently funny films, not just in part. For the next entry, I find that I need to skip forward by over forty years, with:

Young Frankenstein (1974). We enter here, thanks to the genius of Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder, into the realm of post-modernism, ahead of a good decade. As a parody of the classic horror film genre, the film was shot in black and white and with the same narrative and editing techniques employed in 1930s. Sounds intellectual and a bit on the dry side? Not at all. The film is memorably funny, and indeed some of its lines have become famous. Marty Feldman is eccentrically funny as Igor, and so is Teri Garr (do you remember her when she used to be a staple on the Late Night with David Letterman? She often displayed in that context her comic talent, and it is very noticeable in this film). Gene Wilder acts like a man possessed, and the entire work is a riotously funny pastiche, at once spoof and homage to the pre-modern era of film-making.

Young Frankenstein (1974). We enter here, thanks to the genius of Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder, into the realm of post-modernism, ahead of a good decade. As a parody of the classic horror film genre, the film was shot in black and white and with the same narrative and editing techniques employed in 1930s. Sounds intellectual and a bit on the dry side? Not at all. The film is memorably funny, and indeed some of its lines have become famous. Marty Feldman is eccentrically funny as Igor, and so is Teri Garr (do you remember her when she used to be a staple on the Late Night with David Letterman? She often displayed in that context her comic talent, and it is very noticeable in this film). Gene Wilder acts like a man possessed, and the entire work is a riotously funny pastiche, at once spoof and homage to the pre-modern era of film-making.

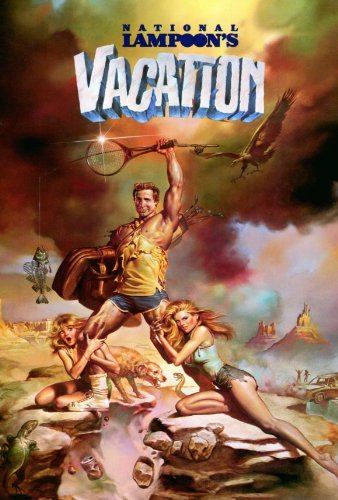

National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983) Suburban patriarch Clark Griswold, a Chevy Chase at his best, decides to spend more time with his wife and two children, and embarks, in a beat-up, out-sized station wagon, on a cross-country trip from Chicago to the Los Angeles amusement park Walley World. The trip should all be about bonding and quality time, but it turns into a mishap fest. Inter alia, the Griswolds inadvertently kill a dog, tie the deceased aunt on the roof of the car, you get the picture, while the patriarch is recurrently tantalized by a gorgeous blonde driving by in a Ferrari. Some of the conflicts young parents experience are hinted at in passing, and all the more strikingly because of such a light-handed treatment: the father’s nagging suspicion, for example, that he may be more interested in chasing beautiful girls than in spending quality time with his children; that married life is, in fact, constrictive; that his wife may be beautiful but man is naturally polygamous… Eventually, Walley World becomes, rather than a destination, a fixation. The Griswolds will reach it, at long last, even though that too will turn out to be an anti-climax. On the way there, the watcher will be laughing all along.

National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983) Suburban patriarch Clark Griswold, a Chevy Chase at his best, decides to spend more time with his wife and two children, and embarks, in a beat-up, out-sized station wagon, on a cross-country trip from Chicago to the Los Angeles amusement park Walley World. The trip should all be about bonding and quality time, but it turns into a mishap fest. Inter alia, the Griswolds inadvertently kill a dog, tie the deceased aunt on the roof of the car, you get the picture, while the patriarch is recurrently tantalized by a gorgeous blonde driving by in a Ferrari. Some of the conflicts young parents experience are hinted at in passing, and all the more strikingly because of such a light-handed treatment: the father’s nagging suspicion, for example, that he may be more interested in chasing beautiful girls than in spending quality time with his children; that married life is, in fact, constrictive; that his wife may be beautiful but man is naturally polygamous… Eventually, Walley World becomes, rather than a destination, a fixation. The Griswolds will reach it, at long last, even though that too will turn out to be an anti-climax. On the way there, the watcher will be laughing all along.

This is Spinal Tap (1984) is Rob Reiner “mockumentary”, co-written with Christopher Guest, Michael McKean and Harry Shearer who also starred in it respectively as Nigel Tufnel, David St. Hubbins and Derek Smalls. Spinal Tap, a British band that has been active for seventeen years with many ups and down, come to the States on tour to promote their latest album, Smell the Glove. Rob Reiner appears as Marty Di Bergi, a film director who is shooting a documentary about this particular tour, which will go from bad to worse to catastrophic. Although everything is fictitious, the overall effect is extremely realistic. Indeed, the film is a compendium of many classic tropes of rock’n’roll: the meddling girlfriend who threatens the band’s unity; the obnoxious promoter; the overworked, slimy manager; the two-word album review; the in-studio fight; the Stonehenge (and similar) stage prop; the band name changes; the disappearing drummer; losing musical direction and turning to jazz; being on the “Where Are They Now?” radio or TV show; not to mention the legendary amplifier that goes to 11.

This is Spinal Tap (1984) is Rob Reiner “mockumentary”, co-written with Christopher Guest, Michael McKean and Harry Shearer who also starred in it respectively as Nigel Tufnel, David St. Hubbins and Derek Smalls. Spinal Tap, a British band that has been active for seventeen years with many ups and down, come to the States on tour to promote their latest album, Smell the Glove. Rob Reiner appears as Marty Di Bergi, a film director who is shooting a documentary about this particular tour, which will go from bad to worse to catastrophic. Although everything is fictitious, the overall effect is extremely realistic. Indeed, the film is a compendium of many classic tropes of rock’n’roll: the meddling girlfriend who threatens the band’s unity; the obnoxious promoter; the overworked, slimy manager; the two-word album review; the in-studio fight; the Stonehenge (and similar) stage prop; the band name changes; the disappearing drummer; losing musical direction and turning to jazz; being on the “Where Are They Now?” radio or TV show; not to mention the legendary amplifier that goes to 11.

When I first reviewed the film, about thirty years ago, I found it analogous to Don Quixote, of all things. The members of Spinal Tap are presented as immense fools, and it’s only human to laugh at them, from the very start to the end, as if they were the Three Stooges with musical instruments. But their trespasses are so benign that it is hard to hold anything against them. In fact, we laugh at them, and yet we feel for them, and are relieved by the film’s improbable happy ending. Centuries before, Cervantes accomplished the same with his Don Quixote: we laugh at the fool and at his foolish trespasses while at the same time we feel for him. Cervantes set out to write a parody of chivalry—he succeeded triumphantly, and yet immortalized it. Rob Reiner, and his co-writers, set out to film a parody of rock’n’roll—they too succeeded triumphantly, and yet immortalized it.

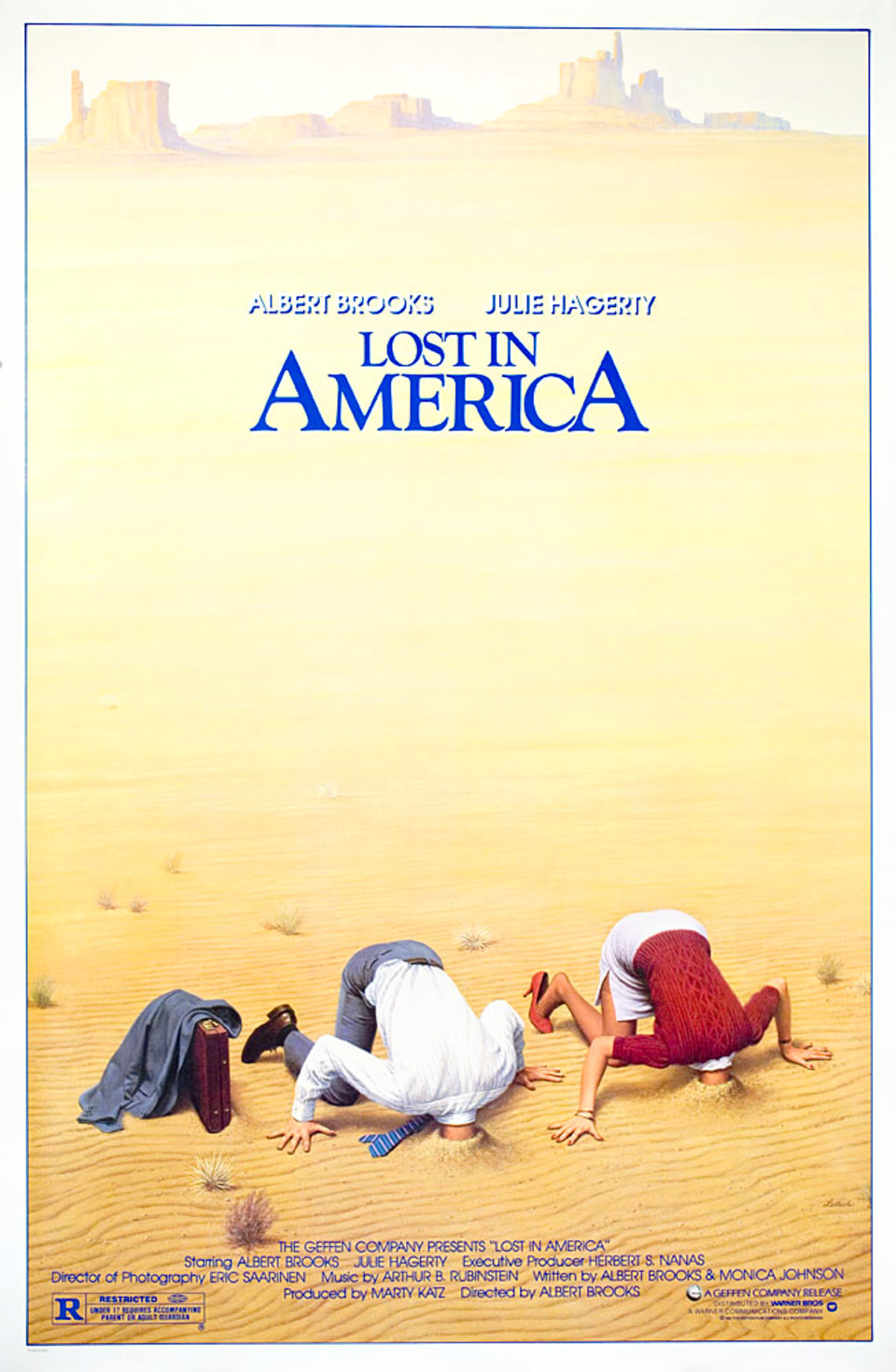

Lost in America (1985) Two yuppies, David (Albert Brooks) and Linda (Julie Hagerty, of Airplane! fame), drop out of the rat race (or rather, David is fired when he was, in fact, expecting a promotion and kept coveting his fetish, a brand new BMW “with leather interiors”). After selling everything they own, they hit the road in a motor home, Easy Rider having quickly become their new fetish, or at least his, bent on doing everything they dreamed of in their youth, such as, “We have to touch indians!” Soon enough their new life goes south: in Las Vegas, unbeknownst to her husband, Linda gambles away their entire “nest egg.” David is devastated, but quickly comes up with a plan. He meets with the casino’s director, who looks and speaks like a stereotypical Mafioso, and illustrates to him “the boldest experiment in advertising history: you give us our money back.” It’s one of many brilliant scenes. Many comical complications ensue. Albert Brooks would never be this inspired again, both as a director and as an actor. The film is a tremendously accomplished commentary not just on the 1980s, but on human nature in general. And it’s funny throughout.

Lost in America (1985) Two yuppies, David (Albert Brooks) and Linda (Julie Hagerty, of Airplane! fame), drop out of the rat race (or rather, David is fired when he was, in fact, expecting a promotion and kept coveting his fetish, a brand new BMW “with leather interiors”). After selling everything they own, they hit the road in a motor home, Easy Rider having quickly become their new fetish, or at least his, bent on doing everything they dreamed of in their youth, such as, “We have to touch indians!” Soon enough their new life goes south: in Las Vegas, unbeknownst to her husband, Linda gambles away their entire “nest egg.” David is devastated, but quickly comes up with a plan. He meets with the casino’s director, who looks and speaks like a stereotypical Mafioso, and illustrates to him “the boldest experiment in advertising history: you give us our money back.” It’s one of many brilliant scenes. Many comical complications ensue. Albert Brooks would never be this inspired again, both as a director and as an actor. The film is a tremendously accomplished commentary not just on the 1980s, but on human nature in general. And it’s funny throughout.

The Big Lebowski (1998) It’s no secret that this is my all-time favorite film, not just comedy, as I have published essays about it. Rivers of ink have been spent on this film, and with good reason. From a strictly comical perspective, it may also qualify as one of the funniest of all times. The interaction between the Dude and his manic friend Walter is one of the best ever realized on screen, and many other minor characters are very funny. Absurdist situations abound, and this is the Cohen Brothers’ masterpiece. The fact that their previous Fargo would be covered in awards from the world over and The Big Lebowski considered a miss by most critics when it was first released corroborates what I write in the introduction: Fargo showcases various murders and plenty of blood, so it’s deserving of critical attention as a tragedy, particularly in a country in which the gun culture is all-pervading; the infinitely more sophisticated The Big Lebowski is light fare, comical, and dismissible. At least some of such critics have changed their mind since; regardless of what they opine, the film has become yet another cult classic, spawning even an annual festival, the Lebowski Fest. This is the one, truly unmissable film. I’ve watched it many, many times, once in a remote corner of Iceland, at around 3 A.M. as an aurora borealis expedition had failed, with subtitles in Icelandic; the natives watching along with us knew nothing about the film, but soon enough they began to laugh—and never stopped.

The Big Lebowski (1998) It’s no secret that this is my all-time favorite film, not just comedy, as I have published essays about it. Rivers of ink have been spent on this film, and with good reason. From a strictly comical perspective, it may also qualify as one of the funniest of all times. The interaction between the Dude and his manic friend Walter is one of the best ever realized on screen, and many other minor characters are very funny. Absurdist situations abound, and this is the Cohen Brothers’ masterpiece. The fact that their previous Fargo would be covered in awards from the world over and The Big Lebowski considered a miss by most critics when it was first released corroborates what I write in the introduction: Fargo showcases various murders and plenty of blood, so it’s deserving of critical attention as a tragedy, particularly in a country in which the gun culture is all-pervading; the infinitely more sophisticated The Big Lebowski is light fare, comical, and dismissible. At least some of such critics have changed their mind since; regardless of what they opine, the film has become yet another cult classic, spawning even an annual festival, the Lebowski Fest. This is the one, truly unmissable film. I’ve watched it many, many times, once in a remote corner of Iceland, at around 3 A.M. as an aurora borealis expedition had failed, with subtitles in Icelandic; the natives watching along with us knew nothing about the film, but soon enough they began to laugh—and never stopped.

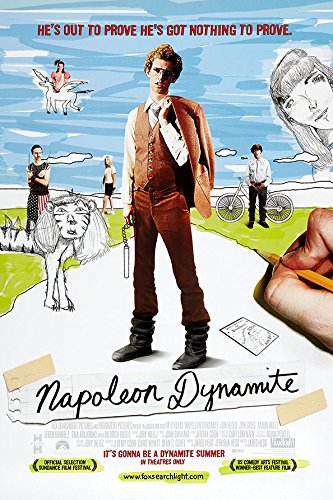

Napoleon Dynamite (2004) Jon Herder stars as Seth, “super nerd extraordinaire” in Jared and Jerusha Hess’s treatise on teenage awkwardness, alienation and dysfunctionality. Though as low-budget and independent as it gets, the film eschews the trite angst-ridden atmosphere of most indies and delivers a portrayal of surreal abnormality within the realm of the normal: a 16-year-old who goes to high school hating just about every minute of his life in a very surreal setting, Idaho looking at times like the moon, and in an equally bizarre domestic context—his quad-bike-riding grandmother; his memorable (I-could-have-been-a-contender) Uncle Rico; his weird brother who hooks up on line with LaFawnduh, who comes to visit him from Detroit. Laughter is born out of Seth’s deadpan one-liners and out of the bizarre situations in which he finds himself. A small comic masterpiece. Oh, not surprisingly the late critic Roger Ebert gave the film one-and-a-half stars.

Napoleon Dynamite (2004) Jon Herder stars as Seth, “super nerd extraordinaire” in Jared and Jerusha Hess’s treatise on teenage awkwardness, alienation and dysfunctionality. Though as low-budget and independent as it gets, the film eschews the trite angst-ridden atmosphere of most indies and delivers a portrayal of surreal abnormality within the realm of the normal: a 16-year-old who goes to high school hating just about every minute of his life in a very surreal setting, Idaho looking at times like the moon, and in an equally bizarre domestic context—his quad-bike-riding grandmother; his memorable (I-could-have-been-a-contender) Uncle Rico; his weird brother who hooks up on line with LaFawnduh, who comes to visit him from Detroit. Laughter is born out of Seth’s deadpan one-liners and out of the bizarre situations in which he finds himself. A small comic masterpiece. Oh, not surprisingly the late critic Roger Ebert gave the film one-and-a-half stars.

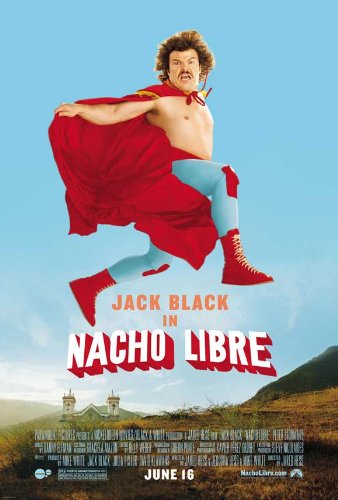

Nacho Libre (2006) Jared and Jerusha Hess’s follow-up to Napoleon Dynamite is another gem. The film is inspired by Fray Tormenta (Friar Storm), a Mexican priest who, for over two decades, competed as a wrestler in order to support an orphanage. It stars Jeff Black in what I deem his best moment, as a low-ranking friar in charge of cooking for his fellow friars and orphaned children. His acting is so pompous, so over the top, it is reminiscent of Oliver Hardy at his most histrionic. His foil Esqueleto (which means “skeleton” and is played by the indeed skeletal Héctor Jiménez) at times steals the spotlight with some absurd lines such as, “I don’t know why you always have to be judging me because I only believe in science.” The film is a supremely reussi pastiche of lucha libre, deliberate kitsch, catechism, bits of Spanish and bits of English with a strong Spanish accent, and the overall look of a Spanish or Italian B movie from the 1960s. Some critics found it offensive for its treatment of Catholicism, Mexicans, midgets and even orphans, when Esqueleto states, “I’m sick of hearing about your stupid orphans; I hate orphans!” But comedy transcends such strictures (“offensive”? Isn’t it a universal instinct to laugh about someone else’s disgrace, at the very heart of comedy since it began?), or in fact thrives on them, as amply demonstrated by the next entry.

Nacho Libre (2006) Jared and Jerusha Hess’s follow-up to Napoleon Dynamite is another gem. The film is inspired by Fray Tormenta (Friar Storm), a Mexican priest who, for over two decades, competed as a wrestler in order to support an orphanage. It stars Jeff Black in what I deem his best moment, as a low-ranking friar in charge of cooking for his fellow friars and orphaned children. His acting is so pompous, so over the top, it is reminiscent of Oliver Hardy at his most histrionic. His foil Esqueleto (which means “skeleton” and is played by the indeed skeletal Héctor Jiménez) at times steals the spotlight with some absurd lines such as, “I don’t know why you always have to be judging me because I only believe in science.” The film is a supremely reussi pastiche of lucha libre, deliberate kitsch, catechism, bits of Spanish and bits of English with a strong Spanish accent, and the overall look of a Spanish or Italian B movie from the 1960s. Some critics found it offensive for its treatment of Catholicism, Mexicans, midgets and even orphans, when Esqueleto states, “I’m sick of hearing about your stupid orphans; I hate orphans!” But comedy transcends such strictures (“offensive”? Isn’t it a universal instinct to laugh about someone else’s disgrace, at the very heart of comedy since it began?), or in fact thrives on them, as amply demonstrated by the next entry.

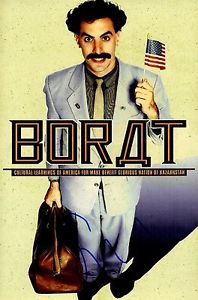

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006) With the character of Ali G, Sacha Baron Cohen had given more than hints of his comic talent. But it is with the character of Borat Sagdiyev that his comicality turned into genius. Borat: Cultural Learnings etc. is a mockumentary about Borat, a Kazakh journalist who comes to the States with a great deal of enthusiasm, ignorance, and prejudices alike, and is not shy about any of the three categories when dealing with real-life Americans. The stratagem allows Sacha Baron Cohen to engage in every possible faux pas, from chauvinism to racism (particularly anti-Semitism), to sexism and on and on. The viewer cringes at most of his jokes, and yet laughing is inevitable. The idea at the core of the film is as clever as the one at the core of This is Spinal Tap. Rob Reiner’s offering is put together better, the writing is more consistent, and there are no gross-out scenes (which aren’t necessarily funny just because they’re gross). Borat: Cultural Learnings doesn’t only explore the very forbidden territory of the very politically incorrect, but at the same time of the very lowbrow. Having said that, this is a work of comic genius, and what it may lack in structure it makes up for with a more than memorable performance. One of the funniest films of all times, including its outtakes, of which there is an ample collection on YouTube.

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006) With the character of Ali G, Sacha Baron Cohen had given more than hints of his comic talent. But it is with the character of Borat Sagdiyev that his comicality turned into genius. Borat: Cultural Learnings etc. is a mockumentary about Borat, a Kazakh journalist who comes to the States with a great deal of enthusiasm, ignorance, and prejudices alike, and is not shy about any of the three categories when dealing with real-life Americans. The stratagem allows Sacha Baron Cohen to engage in every possible faux pas, from chauvinism to racism (particularly anti-Semitism), to sexism and on and on. The viewer cringes at most of his jokes, and yet laughing is inevitable. The idea at the core of the film is as clever as the one at the core of This is Spinal Tap. Rob Reiner’s offering is put together better, the writing is more consistent, and there are no gross-out scenes (which aren’t necessarily funny just because they’re gross). Borat: Cultural Learnings doesn’t only explore the very forbidden territory of the very politically incorrect, but at the same time of the very lowbrow. Having said that, this is a work of comic genius, and what it may lack in structure it makes up for with a more than memorable performance. One of the funniest films of all times, including its outtakes, of which there is an ample collection on YouTube.

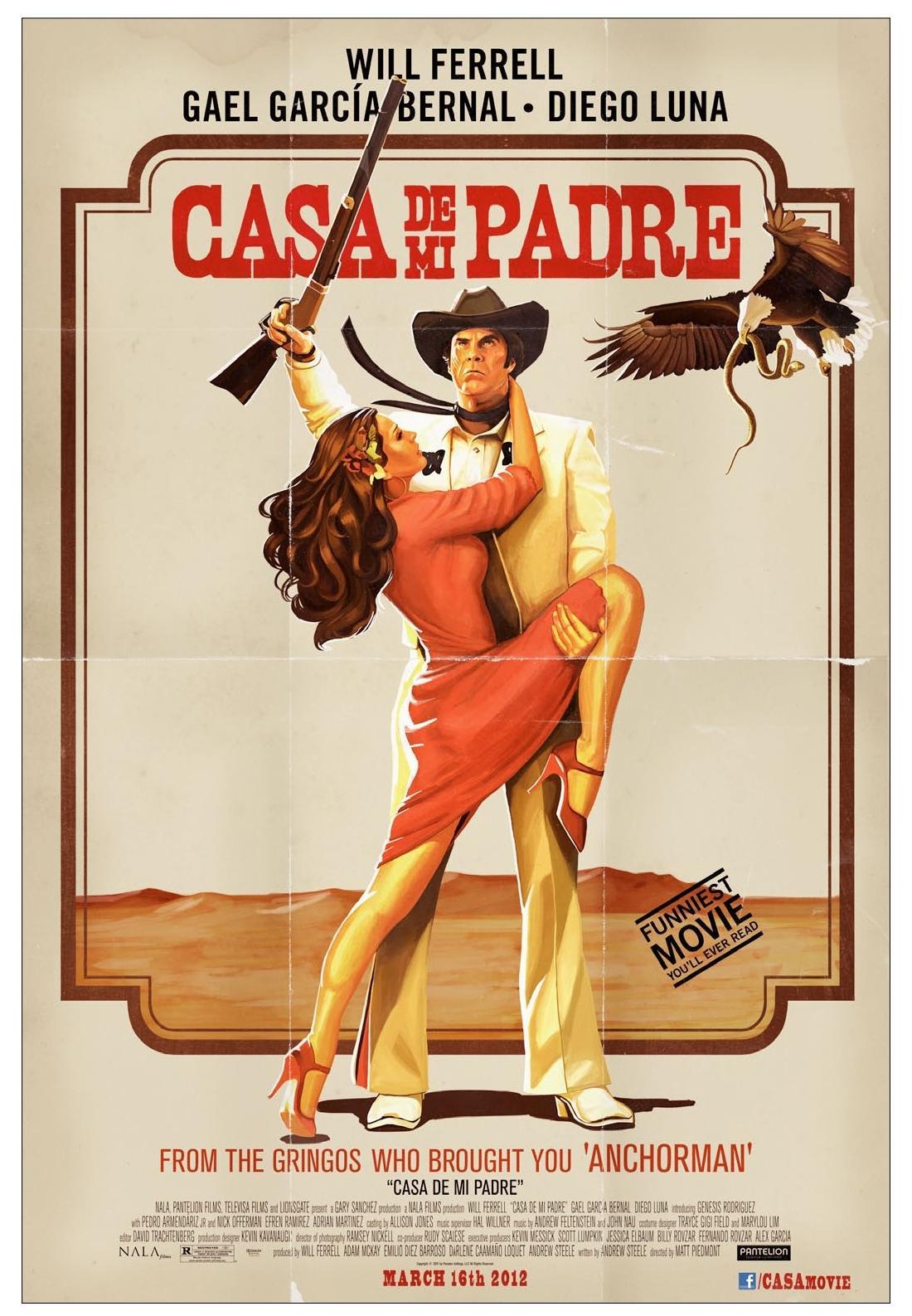

Casa de mi Padre (2012) Here is another oddity, the brainchild of director Matt Piedmont and screenwriter Andrew Steele. Will Ferrell stars as Armando Álvarez, a slow-on-the-uptake ranchero from Mexico. His father’s ranch is being threatened by a local drug lord and he must save it. Will Ferrell acts for the entire time in Spanish, which is hilarious in itself. The film, awash in the ultra-dramatic style typical of telenovelas, teams with absurd situations, and presents at least one instance of truly extreme black humor (you’ll see . . . ). Fluency in Spanish may be a prerequisite in order to enjoy Casa de mi Padre. In which case, it comes off as an incredibly funny film held together by another comic of great talent, Will Farrell, who, by having to act in Spanish, took on quite a challenge and delivered a triumphantly comical performance.

Casa de mi Padre (2012) Here is another oddity, the brainchild of director Matt Piedmont and screenwriter Andrew Steele. Will Ferrell stars as Armando Álvarez, a slow-on-the-uptake ranchero from Mexico. His father’s ranch is being threatened by a local drug lord and he must save it. Will Ferrell acts for the entire time in Spanish, which is hilarious in itself. The film, awash in the ultra-dramatic style typical of telenovelas, teams with absurd situations, and presents at least one instance of truly extreme black humor (you’ll see . . . ). Fluency in Spanish may be a prerequisite in order to enjoy Casa de mi Padre. In which case, it comes off as an incredibly funny film held together by another comic of great talent, Will Farrell, who, by having to act in Spanish, took on quite a challenge and delivered a triumphantly comical performance.

I would add a few foreign-language films.

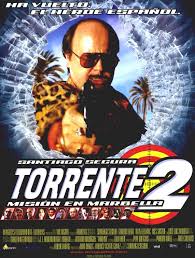

The Spanish Torrente 2: Misión en Marbella (2001), the second installment of the Torrente saga, which began with Torrente, el brazo tonto de la ley (1998), first of four. At the time, this was the highest-grossing movie in the history of Spanish cinema. Torrente is an ex-cop from Madrid, rude/arrogant, lazy, thoroughly dishonest, sexist, lecherous, racist, and Francoist. Well before Borat, we have a lead who seems to thrive on everything that is either politically incorrect, or illegal, illicit, highly cringe-inducing, and just awful. Somehow, however, there is a comic streak in him, and his mishaps make us laugh. I watched this film for the first time years ago at the Miami International Film Festival in the original Spanish, and viewers were laughing so uproariously, it was impossible to hear all the jokes.

The Spanish Torrente 2: Misión en Marbella (2001), the second installment of the Torrente saga, which began with Torrente, el brazo tonto de la ley (1998), first of four. At the time, this was the highest-grossing movie in the history of Spanish cinema. Torrente is an ex-cop from Madrid, rude/arrogant, lazy, thoroughly dishonest, sexist, lecherous, racist, and Francoist. Well before Borat, we have a lead who seems to thrive on everything that is either politically incorrect, or illegal, illicit, highly cringe-inducing, and just awful. Somehow, however, there is a comic streak in him, and his mishaps make us laugh. I watched this film for the first time years ago at the Miami International Film Festival in the original Spanish, and viewers were laughing so uproariously, it was impossible to hear all the jokes.

The Italian Fantozzi (1975), first of many in the saga. Fantozzi  is the archetype of the extremely sycophantic, totally frustrated, perennially-out-of-luck and overexploited clerk lacking in class consciousness and working as the lowest level as an accountant of sorts for a very large, impersonal and alienating company. At the same time, he is shown to be mean-spirited, whenever he can; he finds his daughter, for example, unbearably ugly and lusts after a female colleague, who hardly realizes he exists except for when she needs a favor at work. Hugely popular in Italy, the character Fantozzi has become archetypal, and the adjective “fantozziano” is used to describe a situation in which Fantozzi may find himself. Paolo Villaggio, who wrote the books on which this and the subsequent installments are based and also stars as Fantozzi, was a world-class comic.

is the archetype of the extremely sycophantic, totally frustrated, perennially-out-of-luck and overexploited clerk lacking in class consciousness and working as the lowest level as an accountant of sorts for a very large, impersonal and alienating company. At the same time, he is shown to be mean-spirited, whenever he can; he finds his daughter, for example, unbearably ugly and lusts after a female colleague, who hardly realizes he exists except for when she needs a favor at work. Hugely popular in Italy, the character Fantozzi has become archetypal, and the adjective “fantozziano” is used to describe a situation in which Fantozzi may find himself. Paolo Villaggio, who wrote the books on which this and the subsequent installments are based and also stars as Fantozzi, was a world-class comic.

Lastly, the French Les Visiteurs (1993) [remade in the States, and punctually ruined, as Just Visiting (2001)], the first in a trilogy. This is the ultimate variation on the fish-out-of-water theme: because of a wizard’s magical spell, a 12th-century knight and his squire travel in time to the end of the 20th century and, willy-nilly, have to confront the modern world. Every situation is hilarious, often trespassing into the farcical. Jean Reno plays the knight with a straight face, and the considerable differences in how society was conceived in the Middle Ages and now come to the fore. The subtext of the original French version is strikingly counterrevolutionary (France being the birthplace of the famous, or rather infamous Revolution), while the American remake is in favor of emancipation and democracy, much to the squire’s joy. This was the number 1 box office movie in France in 1993.

Lastly, the French Les Visiteurs (1993) [remade in the States, and punctually ruined, as Just Visiting (2001)], the first in a trilogy. This is the ultimate variation on the fish-out-of-water theme: because of a wizard’s magical spell, a 12th-century knight and his squire travel in time to the end of the 20th century and, willy-nilly, have to confront the modern world. Every situation is hilarious, often trespassing into the farcical. Jean Reno plays the knight with a straight face, and the considerable differences in how society was conceived in the Middle Ages and now come to the fore. The subtext of the original French version is strikingly counterrevolutionary (France being the birthplace of the famous, or rather infamous Revolution), while the American remake is in favor of emancipation and democracy, much to the squire’s joy. This was the number 1 box office movie in France in 1993.

_______________________________

Guido Mina di Sospiro was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an ancient Italian family. He was raised in Milan, Italy and was educated at the University of Pavia as well as the USC School of Cinema-Television, now known as USC School of Cinematic Arts. He has been living in the United States since the 1980s, currently near Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books including, The Story of Yew, The Forbidden Book, and The Metaphysics of Ping Pong.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link