Interesting Concept

by Kenneth Francis (August 2022)

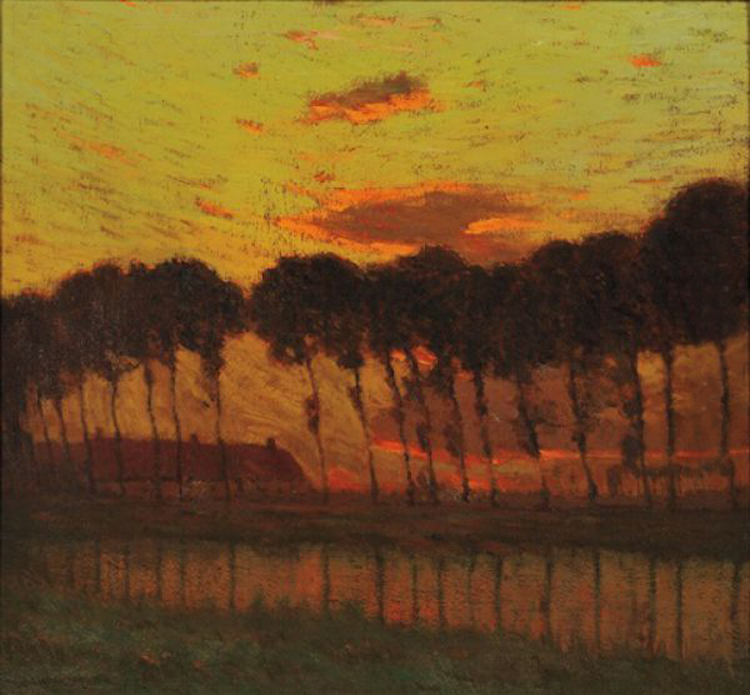

Sunset Through a Row of Trees, Charles Warren Eaton

“Hi, my name is Steve, let’s talk about phenomenology.”

That would be a bad chat-up line for any single man to say to a woman, despite it being an interesting concept worth discussing. Interestingly, the person who utters such words would see the ‘object’ of his desire as more than a sack of molecules in motion, but instead someone endowed with beauty in motion as well as, hopefully, having a loving heart.

On first sight, he would see her immediately in a phenomenological way and not scientifically. I refer here, of course, to the primary world of phenomenology and not the clown subculture we have to occasionally endure on Planet Woke, where genders should not be assumed and chatting up a woman is retardedly perceived by deeply unhappy people as a psychological sexual assault.

In the real, sane world, phenomenology as a way of perceiving reality, was developed earlier in the 20th century by the philosopher Edmund Husserl. Besides men admiring attractive women in bars, the subject has many theological implications in biblical hermeneutics, as well as how the average person’s consciousness perceives the reality of the external world.

Some 14 years ago, I interviewed the world’s leading scholar in phenomenally, Professor Dermot Moran. What struck me about professor Moran, was his lucidity when describing philosophical matters, as well as him being quite a pleasant chap to converse with.

I had just read his big book, Introduction to Phenomenology, which was described by David Bell from the University of Sheffield, as “the most accessible, the most scholarly, and philosophically the most interesting account of the phenomenological movement yet written.” With this in mind, I wanted to incorporate some of the ideas into a book I was writing on the Irish philosopher, George Berkeley, who I’ll come to later.

I had already interviewed a Berkeley scholar at Trinity College about Berkeley’s Idealism but wanted to expand my knowledge of phenomenology. For the lay-person, phenomenology can be a little complex, but I hope to make it as accessible as possible in the following paragraphs by giving a few examples.

Let us start with the objective reality of the external world and how we perceive it. Scientifically (secondary), we describe it quantitatively, whereas phenomenologically (primary), we describe it in an immediate way without any deep analysis. An example of phenomenology is when we see the sun rise or set, while an example of the scientific method describes the earth tilting for both sunrise and sunset.

Another example of the scientific method is the description of a tree and the various components which it contains: molecules, atoms, its shape, height, weight, age, etc. On phenomenology, our immediate perception is that of a beautiful tree with a trunk, branches and leaves. We might even want to sit under it for shelter from the rain or shade from the sun. The last thing we want to do is measure it, unless, of course, one is a tree surgeon or a botanist doing research.

In our everyday lives, we certainly don’t use the scientific method for the majority of our actions. When ‘putting the kettle on’ for a cup tea, we don’t think of boiling the H2O till the molecules move around and exceed the strength of the hydrogen bonds between the molecules, causing them to separate from the other molecules in order to increase the thermal energy to a heat point of 100C (212F). I can’t remember the last time I made tea, pondering over the intermolecular bonds breaking up as the heat increased the kinetic energy of the system, causing the molecules of the water vapor to move faster with the temperature increasing.

In contrast, phenomenologically, our primary truths and experiences, if functioning properly, are sufficient to tell us all we need to know about an action, event or object. Afternoon tea aside, consider a night at the opera or a day at the races: At the opera, we hear the orchestra playing, while sopranos and tenors sing to rapturous applause, while at the races, we see horses gallop and people cheer, all the while experiencing our five senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell.

However, scientifically, the aforementioned events are a different story of a secondary experience, similar to the boiling water mentioned above; despite this, we can still know reality by its phenomenological truths.

Why is all this important, you might ask yourself. I believe it’s important to understand what it is that give both us and the material world of objects its fundamental structures and mechanisms. Which brings me to theism.

A retired Christian professor of philosophy who I regularly correspond with briefly mentioned that many Catholics don’t have an ‘adult faith.’ The term for such a belief system is ‘properly basic’ or ‘fideism.’ Liking it to phenomenology, such belief is primarily existentially immediate; whereas a more analytical belief is based on hard evidence, similar to the scientific method, based on investigation and/or reasonable faith as opposed to blind faith.

The British philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) made the distinction between ideas, immediately aware in perception to people, and material things caused by such ideas. This distinction runs counter to George Berkeley’s philosophy, in that ideas are the first (most immediate) things that spark an awareness in human beings, as in sound, touch, sight, smell, and so forth.

But Locke was trying to find out what is it that is ‘out there’, whereas Berkeley, who was more of a phenomentalist, looks from within as his starting point. Chairs, tables, trees and everything in the so-called material world are not active in the same way as minds are. Berkeley is confident in the knowledge that such objects, unlike minds, are not perceiving and do not have ideas (that’s panpsychism). Everything, he rightly claims, is in the infinite Mind of God.

In Of The Principles Of Human Understanding, Berkeley wrote: “It is indeed an opinion strangely prevailing among men that houses, mountains, rivers and in a word, all sensible objects, have an existence, natural or real, distinct from their being perceived by the understanding … For what are the aforementioned objects but the things we perceive by sense? And what do we perceive besides our own ideas or sensations? And is it plainly repugnant that anyone of these, or any combination of them, should exist unperceived.”

The ancient Hebrew writers, inspired by the Holy Spirit, had to communicate the world and the cosmos in a language that could be immediately understood. To explain things the way Berkeley did or in the scientific method would greatly confuse the masses. Also, these great prophets and scribes had no understanding of modern science.

The opening lines in the Bible tells us, phenomenologically, that ‘In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth,’ and not explained scientifically as: ‘During the Big Bang, a disembodied triune all-powerful Mind/Spirit set in motion trillions of balls of gas, time, space and matter.’ Such scientific notions and explanations of the cosmos mean nothing to us as we gaze into the night sky and see God’s creation in all its glory.

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 30 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing) and, most recently, The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Theodore Dalrymple) and Neither Trumpets Nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Samuel Hux).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast