Julián Marías, The Media, and Public Intellectuals

by Pedro Blas González (October 2024)

There is a tendency of our times that preoccupies me a lot, and this is the tendency that consists in evading the irrevocable, in trying to conceal the radical character of human life – which is that and nothing else. —Julián Marías, Philosophy as Dramatic Theory

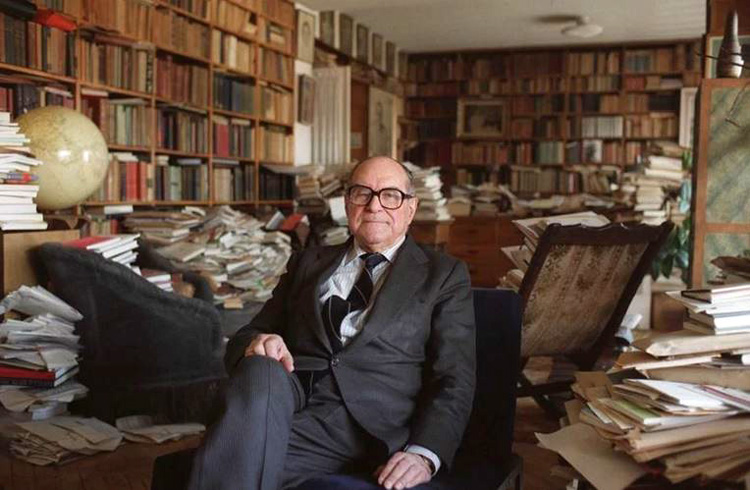

The Spanish philosopher Julián Marías (1914-2005) is a gifted thinker whose essays disseminate complex concepts in a manner that is never pedantic. This is a rare gift in thinkers. His ability to write without pretense and jargon is truly commendable.

Marías’ friend, José Ortega y Gasset, for whom writing philosophical essays in newspapers was a manner of elevating the level of discourse in newspapers, understood the role of public intellectuals as a great opportunity to enlighten. Marías published essays on culture, art, moral concerns, literature, cinema, and many other subjects in popular publications with the same flair and respect for clarity that he demonstrates in his sixty-six books.

Marías was a responsible public intellectual and fulfilled that role with dignity. He did not solicit celebrity, power or admission into the cult of personality. This is a temptation that only those who possess a genuine desire for philosophical reflection seem to avoid.

While newspaper commentaries limit the depth of themes that a writer can develop, it does not limit the topics of discussion, especially if these are hot-button, fashionable concerns. Marías was conscientious and discreet in this regard as well. He is a fine example of a thinker who can discuss serious topics, while successfully engaging a thoughtful and well-rounded reading public in the exercise of prudence and moderation.

His hundreds of newspaper and magazines columns are the result of serious and profound thought and his ability to communicate the importance of lasting and eternal concerns to thoughtful readers. Not being an academic, Marías kept himself motivated by the pursuit of truth, not the timely glare of institutions and ideology. His thought comes across clear and polished, not contrived or hackneyed, as is the case with many hapless ideological academics.

Also central to Marías work is his respect for Christian and humanistic philosophical categories. Marías was cognizant of the immeasurable damage that has been done to philosophy and culture by proponents of fashionable, chic theories. Keeping a discreet distance from timely, attention-seeking, he managed to create a body of work that underscores the importance of man’s personal worth and the gravitas that promotes the pursuit of the Socratic good life.

As a writer for Spanish periodicals and magazines like ABC, ABC Cultural, and Blanco y Negro, Marías developed an effective manner of communicating philosophically with a general public that serves as a role model and the envy of many lesser thinkers. Marías understood the necessity and importance of communicating with thoughtful readers who embrace and cultivate philosophical reflection.

The flexibility that Marías was forced to develop in order to communicate with an audience of non-specialists in philosophy allowed him to comment on important topics, without intimidating or alienating his readers. In his case, this labor of love had two significant consequences: the use of popular means to introduce profound analysis, and to demonstrate the usefulness of philosophy in addressing poignant vital and existential concerns. This is in keeping with the spirit and value of philosophical reflection.

The flexibility that Marías was forced to develop in order to communicate with an audience of non-specialists in philosophy allowed him to comment on important topics, without intimidating or alienating his readers. In his case, this labor of love had two significant consequences: the use of popular means to introduce profound analysis, and to demonstrate the usefulness of philosophy in addressing poignant vital and existential concerns. This is in keeping with the spirit and value of philosophical reflection.

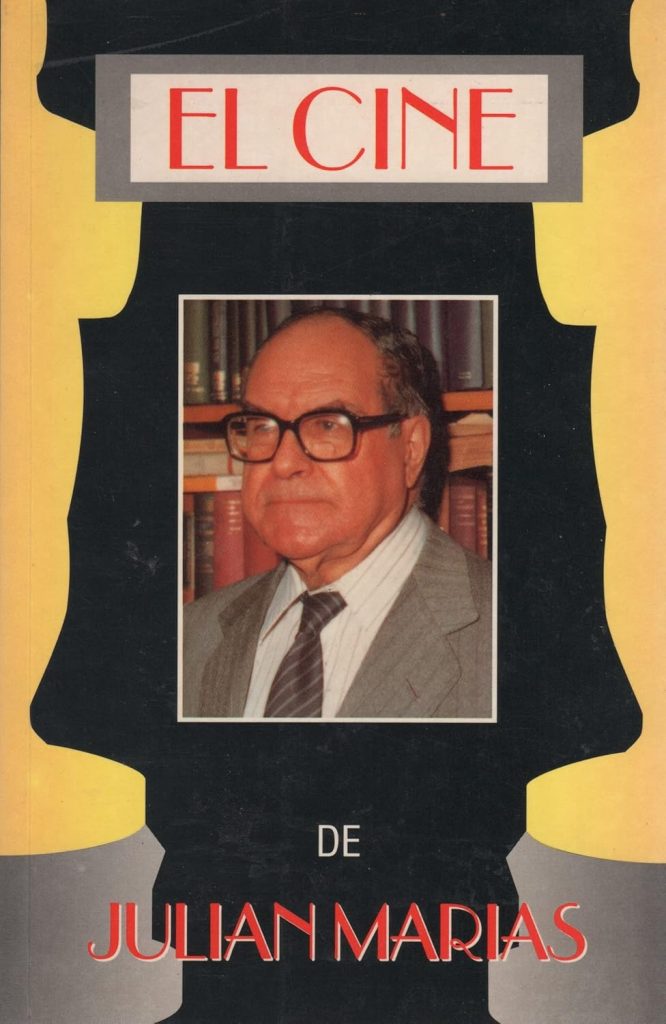

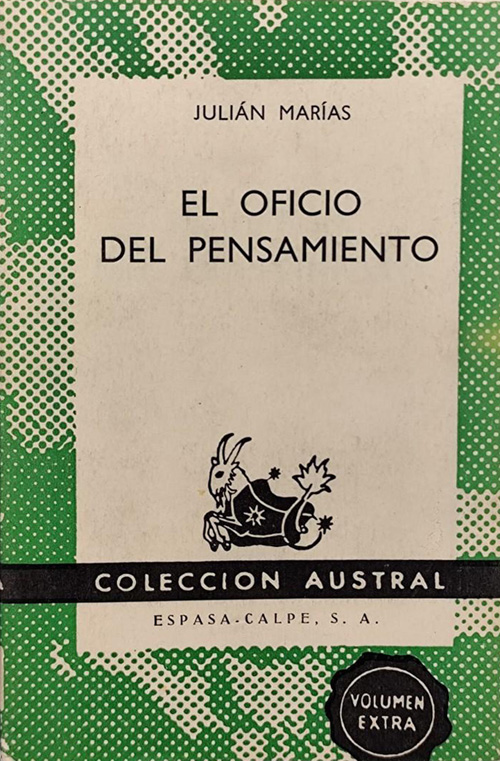

For instance, his two volumes of essays on cinema titled El cine de Julian Marías are comprised of essays that he wrote for ABC and Blanco y Negro. I imagine that quite a few readers are surprised to hear that the author of Filosofia actual y existencialismo en España and El oficio del pensamiento could also be interested in the Marx Brothers. Marías offers a humble philosophical perspective on cinema that does not suffer from theoretical and ideological inebriation.

His essays on cinema do not go out of their way to deconstruct, that is, dismantle the motives of a given director. Marías writes about cinema much the same way that he writes about other topics: from a philosophical vocation to address important human concerns. The films that Marías writes about are films that he has watched of his own accord, and not necessarily having to satisfy the role of the critic. Many of these are films that date back to the Golden Age of cinema, especially American cinema.

Marías explicates and augments the themes that writers and directors develop. There is nothing fashionable about his essays on cinema. His writing is sincere and always life-affirming. He offers his measured and nuanced analysis to readers who may be interested in a philosopher’s take on cinema. Consider what he writes about Duck Soup: “Duck Soup is different from other Marx Brothers films in two or three counts; it is less verbal and more visual, that is, something is always happening, and the hilarious action is never interrupted; the ‘no stopping’ is more literal than ever; it has a curious reiteration element, which I will comment on, is more intentional than in their other films.”

Marías practiced philosophical vocation in the most appropriate way possible: he embodied it as a way of life. The difficulty, as well as the grand aspect of philosophical reflection, is knowing how to exercise this tool in the service of life.

On the other hand, the absence of genuine vocation creates a carapace that some may call ‘academic philosophy,’ but which when measured against lived, vital philosophy proper, boils down to nothing other than a sterile academic enterprise, a feel-good, ideological mind-numbing candy.

Marías understood that sincere philosophical reflection does not allow itself to become sidetracked by fame or the latest intellectual fashion. He was concerned with the banality that he witnessed issuing forth, especially since the second half of the twentieth century, from fashionable writers who sought fame and fortune, individuals who are enamored of power.

Marías understood that sincere philosophical reflection does not allow itself to become sidetracked by fame or the latest intellectual fashion. He was concerned with the banality that he witnessed issuing forth, especially since the second half of the twentieth century, from fashionable writers who sought fame and fortune, individuals who are enamored of power.

Marías was particularly critical of the overabundance of literary prizes that he believed weaken the merit of literature. He ties the cottage industry of prize-giving to a marked decline in artistic quality. He explains this in an essay titled “Profundidad”: “The consequence of all of this, of the inequality and lack of richness of the present is the absence of ‘profundity.’ There is an evident diminution of reality of the European Union. The greatness that has been Europe for many centuries has now evaporated.”

This has to do with what he calls the vital process of “daring to be,” which we find in his essay of the same title. Of course, philosophical reflection and the order of reality are two different things. Philosophical reflection requires profound effort to develop and communicate. Human reality and contingencies demand much from us. Marías’ intellectual sincerity as a thinker comes through in his writing: “The temptation of many writers is to think about prizes as the fountain of inspiration, even though they know that after receiving them they quickly become forgotten. This is a way of coming into fame at the cost of losing loyal readers. It is unsolvable the damage that all of this is doing to culture, to what we refer to exaggeratedly, as ‘creators.’ The common factor that explains this series of apparently heterodox phenomenon is the resistance of attempting to be what one is, that is, authenticity.”

The role of philosophical vocation in Marías’ work cannot be separated from his idea of lived vitality. For Marías, philosophy is a crucial human activity that uncovers the self. This also means exposure for superficial people who are burdened by free will. Yet, far from being an ‘intellectual’ high-brow endeavor, philosophical reflection is instead a reflective task that helps us make practical sense of reality.

Marías argues that we are in possession of reality to the degree that we are first willing to encounter ourselves, and thus determine the kind of being that we are. This act of self-knowledge is never technical. He adds: “Still of greater concern is the perturbation occasioned by the lack of respect of ‘vocation’ itself, perhaps this has to do with the disappearance of vital authenticity. This creates a hole in reality, which is filled by the non existent. In the words of the moribund Quevedo, ‘what is nothing other than a vocabulary and a figure.’”

Marías’ essays, the vast majority which appeared in ABC Cultural, are refreshing and insightful. These essays are dominated by common sense, a virtue that is not very common in postmodernity. In many respects, Marías’ essays are an assault against the war that postmodern man has declared on human reality. He tells us in his essay, “Reality and its Masks”: “We are witnessing a process that can be called an ‘offensive’ against reality.”

No doubt, this offensive will continue to intensify in the near future. He writes: “It is not easy to destroy what is real. Even risking it involves many risks but this is within reach of those who want to occult, disfigure and supplant it with other things. In conclusion, to occlude it.”

Table of Contents

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy in Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998). His most recent book is Philosophical Perspective on Cinema.