by Tricia Warren (June 2023)

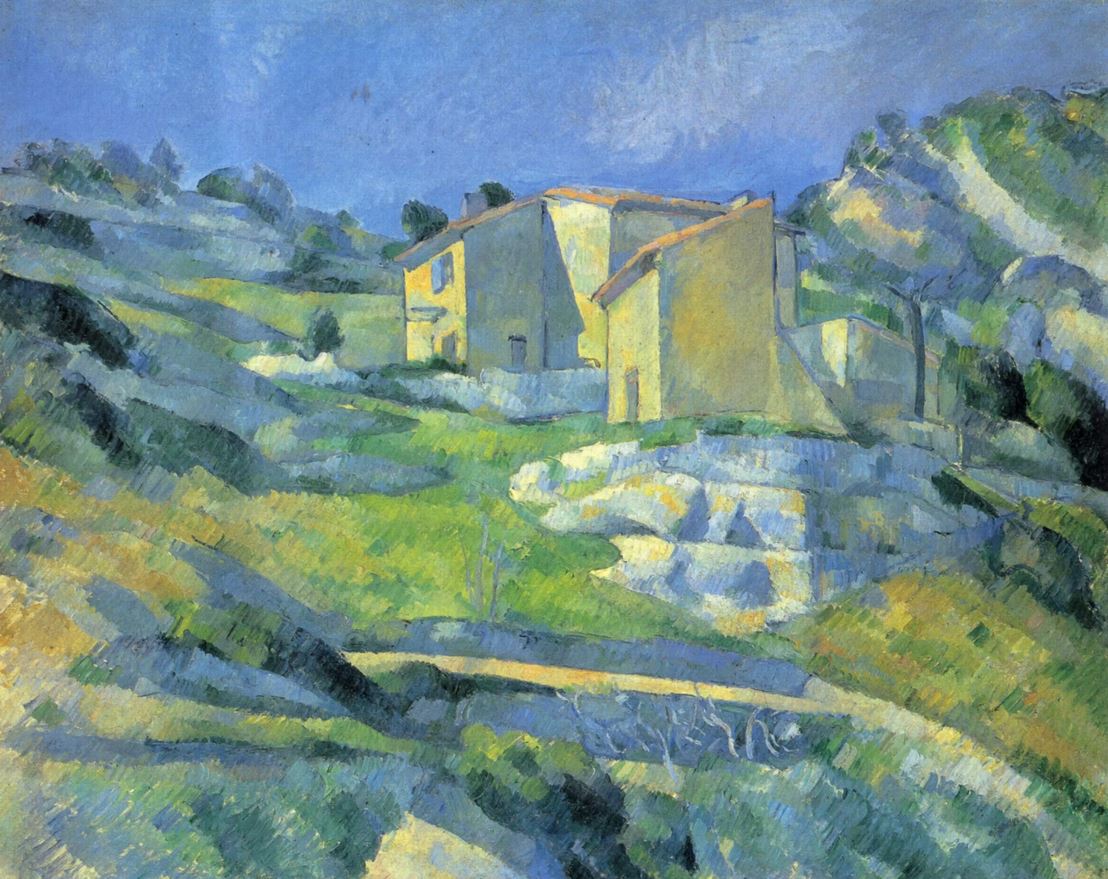

House in Provence, Paul Cezanne, 1882

Usually around ten, Jocelyn savored cappuccino then, after a fashion, checked emails, but on this particular morning—even with her forearms benumbed by countless early check-outs—she tapped intently, mellifluously, like a concert pianist. According to her colleague Sean, who had heard it from Cidnei, an executive office assistant, promotion notices were going out that day. “Via email,” said Cidnei, no doubt in her all-knowing tone. And if only to escape her present job—the aforementioned frenzy, hotel guests’ buffeting—Jocelyn hoped to receive one, perhaps a dazzler like the neon-green email she’d received for high school Governor’s Honors, possibly—since college had fizzled like a days-old balloon—the apogee of her existence thus far. Whereas at Registration, except when she bantered with Sean, words like “apogee” rarely surfaced, neither when she helped guests, nor when she became quiet and ornamental as the chrome and vinyl lobby chairs.

Either way, given the Gilmore’s wi-fi speed, the website’s blue ribbon wasn’t budging. Frustrated, she rubbed her thick brows, roundish face, and hazel eyes that her ex-boyfriend swore glimmered with blue flecks. Hunched forward, tucking her calves beneath the swivel chair, liberating heels and toes from pumps, she considered how authoritative the pumps’ golden buckles had made her look earlier as dawn, fusing metaphysical pink with yellow, bounced through her apartment windows, and voila, her mirror became a pastel.

Unlike those at the Versailles, her misnomer of an apartment complex, the Gilmore windows stretched from floor to ceiling. Rather incongruously they overlooked a flat office park lake that reflected the hotel plus an office building, the Gilmore’s shiny replica. “Twin Towers,” the two were called, for presiding over the suburb’s other hotels, office parks, and cul de sac neighborhoods, and even after 9/11 no one had bothered to change. Only an unsightly pipe protruding from the lake’s fountain marred the ersatz scene, which was so pacifying the deviation barely registered. Hardly had a cluster of T-shirt-clad guests burst into the lobby than they too slouched upon beholding the view.

“Good morning,” she declared, employee handbook-style. (Known as the SCOTT, the handbook charged employees with being “service champs on the team.”) After echoing her wan greetings back at her, they peered outside at the opaque sky, presently resembling a papier mâché mask Jocelyn and her friend Nadia had made once in Girl Scouts, though in the sky version bright tendrils illuminated the edges like hair. Never mind, however, for precisely then her webmail flickered, offering “hot skirts for a hotter YOU,” then a political missive opposing “evil”; but no executive office email.

“Thanks, Pete!” she declared as Peter from the kitchen placed a breakfast bar muffin near her elbow plus the aforementioned cappuccino. Transported by the cranberries’ tartness, their juxtaposition with hot caffeinated froth, she relaxed her forearms on the flat, steel registration desk, anticipating a pristine office with a closable door, her favorite promotion daydream. Upon her imaginary wall she hung a painting, maybe a Cezanne, until an expectant face appeared, looming over the desk. Then the sheen of his head. Perhaps he’d dropped something, bowing his head that way. Or was he praying?

Either way, her reverie was quashed. How she longed to nibble and sip for a bit longer, free from guests’ whims! But sliding her cup and muffin inside the desk’s lower shelf, cringing as shadows wobbled and dust scattered over both, she smiled obligingly instead.

Deep inside a hanging suitcase the man was excavating, only to reappear holding a laundered blue shirt, which he cinched with three others swaying as he jostled them—a ripple of candy pink, blue striped, then yellow—until they hung in a row. “I’d like to check in early,” he said, rolling the luggage cart aside. Onto the desk he plunked a leather wallet, round and smooth as a brown egg.

“Yes, of course.” She stood up, smoothing her skirt over her thighs. If she balked when anyone commented (rather sincere herself, she imagined others transcending superficialities), thanks to a trim physique and searching demeanor she moved nimbly. “May I ask your name?”

But before she could finish her script—would you care for a bottle of water?, etc.—he demanded, “Whatever happened to Mattie?” His glance bounced around Jocelyn, then past her, resting on dust icing the computer, before swiping the inner room like an errant tennis ball. “Long auburn hair,” he added, touching his rondure feebly, as if time’s erosion was so unspeakable only tactile recognition would suffice. “She used to work here.”

“She was the desk manager before me,” Jocelyn said, aware of the whites of his eyes expanding, his head bobbing, the wrinkles in his shirt releasing airplane odors. Though not too aware. Travelers could be odd ducks sometimes, full of obscure tics and reference points dispersed among common ones like sports or political clichés. Better to stick with those. “She quit, mmm, a year ago.” She slid his card through the sensor, whose tiny green bulb flashed affirmatively.

“Wonder where she went.” He tapped the card on the counter, then tucked it inside his billfold, which was quickly whisked out of sight. Two slender fingers swatted a few remaining strands of hair across his damp forehead. So poignant was this gesture that she leaned tenderly over the counter to offer the check-in folder. “We hope you enjoy your stay, Mr. Norris.”

Besotted by images colliding, shifting on his iPhone screen, he left his folder untouched. To borrow from Sean’s lexicon, he “teleported,” not retrieving the folder until a flashing golf course drew him to the lobby TV, leaving Jocelyn free to refresh her inbox. Possibly because Mr. Norris had mistaken her for Mattie’s asterisk, the email’s hackneyed phrases—“regret to inform,” “many qualified candidates”—splintered her thoughts, even defied sense, not to mention her neck throbbed. Never in her three years at the hotel had she received such a note. No great-job-Ms.-King-keep-it-up at the end. A missive from new corporate, not the old.

Given a garish tint yellowing the lobby as sunlight flared outside, the cloudy mask no more, she gathered an array of pizza menus splayed on the desk and reinserted them into their plastic orange holder. Not daring to finish her snack given the email’s “content,” management’s own term for its email, she fumbled beneath the desk until the cup’s warmth radiated through her fingertips while recalling a Quality Control guy, later promoted to upper management, disclosing at the employee retreat as everyone mingled on the terrace that his co-workers sometimes masqueraded as guests. “To monitor desk staff,” he’d hissed, reeking of cheap merlot.

Possibly even Mr. Norris could be a mole, standing beside the waffle tray now, where a hurly burly erupted, the aroma of batter, pan spray, and disinfectant wafting overhead. A boy grabbed a pair of tongs, prompting a girl to try to wrest them away, before he dove under a table, eluding her grasp. Pancake enthusiasts, most likely sibling malcontents; definitely not corporate spies, those two. Emboldened by their levity, Jocelyn pulled out her cup and brazenly swallowed her now-tepid drink, filling her soul—or esophagus?—with a sweet vacancy, until in his usual kinetic way Sean approached, three doughnuts cradled in his palm instead of the usual four.

“Have you seen the email?!” said he.

“Which one?” Zigzagging now between tables carrying stacks of pancakes, the siblings reminded Jocelyn of her brother. Last family gathering, he’d psychoanalyzed everyone present courtesy of his fiancée, a grad student in the subject, who kept tapping her red shoes as if to the rhythms of a recurring song. Dispirited by the memory, Jocelyn eyed Sean, wondering if co-workers might substitute for family.

His first doughnut gone in three bites, Sean gingerly balanced the others upon the desk, and with white, powdery fingertips pulled a copper-hued laptop—picturing a bosomy lady hoisting a sword—from his backpack. “I just got one. They’ve blocked ‘personal access’ on their computers; only ‘activity pertaining to hotel business’ permitted. Also, they’re wiring the premises with ‘interactive video as well as audio recording and monitoring, 24-7.’”

“Do they still use wires? Aren’t those archaic?”

“Dunno.”

“Well, I opposed them. At the meeting. Just got an extra email that I’m not promoted.”

“Dude.”

“Says I’m no team-player. And other banalities.” Nearly toppling herself, she swiveled to avoid the donuts’ powdered sugar landing in Jackson Pollock splotches upon desk and floor.

“That’s okay, Jocie. Ever since my mom died, no one appreciates me, either.”

“I’m sorry,” Jocelyn said, truly sorry about his mom’s early death, and he only twenty-four. But what did he mean, unappreciated? While his eyes, certainly his evocative strawberry lashes, plus his shirt tracing a flat stomach, tucked into trousers that fit rationally in contrast with her own ever-changing physique, so often beguiled, his quips puzzled her.

“And FYI… ”

“Yes?”

“That cup’s plastic lining causes cancer.”

“I saw that too, on Morning.com!” she said, ignoring his challenging undertone. As always, she hoped it would go away.

“Don’t you have a couple days off soon?”

“Starting in about,” she checked her phone, “twenty-five hours. But first I gotta do Nadia’s think-tank dinner; then tomorrow after my early shift I’m free!” That’s how her friend Nadia talked lately: we’ll “do” dinner.

Vigorously munching, Sean coated his lips with powdered sugar, which left several sprinkles, green, purple, pink, dangling from his semi-beard. “How come?”

“How come what?”

“How come dinner?” Ever since COVID, a big dinner seemed like, as her father might say, a “relic from another age.”

“Something about nuclear war.”

“Nuclear what? Nuclear war sucks!” he said, jiggling the sprinkles into his lap, then sprang up as if they were insects and scattered them onto the floor.

“Sean.”

“What.”

“In your view, is that word tiresome?”

“What word?”

“’Sucks.’”

“Well perhaps, your majesty. Why do people down here carp so about manners?”

It was complicated, she supposed: In one sense, crisscrossing freeways in Atlanta, her hometown of sorts, she encountered no such concern, even took herself for genteel because she never exceeded 62 MPH. More traditionally, her father, aunt, uncle, and cousins, without a fuss, said “yes ma’am, yes sir,” and “nice to meet you” to one and all. (Ever since her mother relocated downtown to attend law school, in her words, “so through with the male gaze,” she’d been more equivocal.) Either way, not wanting to elaborate, Jocelyn kicked the sprinkles under the desk, then paraphrasing Nadia’s rhetoric, described the think tank, especially its chairman, Miles Lambert, whose august job titles—former US Congressman, Secretary of State, think tank founder—she practically hissed, feeling the shoulder pads on her navy blazer thicken, her silk blouse dazzle. Surely that’s how anyone whose father wasn’t a Methodist minister spoke. Although basking in Nadia’s professional glow, she couldn’t help but feel like a squished bug in comparison. If loyalty to her most enduring childhood friendship, her perennial excuse, was waning, perhaps she might skip the dinner altogether?

Again the Cezanne from her imaginary office wall—of a pale yellow house, encircled by summer trees bedazzling the river’s surface—wended its way through her mind. How a nineteenth-century idyll meshed with a think tank dinner pertaining to nuclear policy wasn’t clear, but her thoughts sometimes flipped like an unruly garden hose. Like the time she’d asked her dad after a prayer why the Old Testament God demanded homage not unlike an unpleasant boyfriend.

“You sure it isn’t about nuclear power?” Sean interjected. “That wouldn’t be quite as bad; but it’s still bad.” From boredom or angst, he often predicted some debacle or other à la his video games.

“No, I’m not sure.”

“Double negative.”

“You’re offended by double negatives, but not ‘sucks?’”

“You’re offended by ‘sucks’ but not nuclear war?”

“Sheesh—“

“What are you gonna do?”

“Do?” she asked.

Robotically he bounced a departed guest’s pink ball between floor and cabinets, awaiting her answer. “On your two days off?” Bounce, bounce.

“Oh. I dunno.” Almost falling off her ergonomic chair. “Maybe go to a park.”

Sean stared at her face, even cocked a brow, although with him, flourishes were to be expected. The youngest in a business-savvy family—there were his dad, a corporate counsel, and his aunt, a CFO, plus a board member of STAR, a world hunger charity—he’d distinguished himself by performing in college theater, everything from Fiddler to As You Like It. Consequently, when a voice worthy of Tevye or Orlando checked them in, a rarer, observant sort of hotel guest might startle. “Alone?”

“Mmm hmm.”

“What about that guy you were dating, the one who bragged about his family? They owned the land around here, founded the state or something. Is that still over?”

“Yep.” Despite her blasé answer, Sean’s inflections, the way he said “alone,” rankled. “And he isn’t begging for another chance, if that’s what you mean—he’s not that passionate, except about tennis.” When Sean questioned her aggressively, she felt like a pebble was stuck in her throat.

“Aren’t half the streets around here named after his family?”

“In one variation or another: Baldwin Boulevard, Baldwin Manor. But I’m just happy to have—time off.” As if to shake off the Baldwins, Sean, hotel management, nuclear threats— perhaps the entire, tangled grown-up universe—she smiled with bright fakery.

Into another ball Sean wadded the doughnut wrapper before hurling it into the trash. Notwithstanding the pink-orange stubble covering his jaw, he looked boyish, like he might catapult anywhere. So why he framed her own existence, a disparate series of inchoate sensations, events, and non-events, into a scripted movie narrative hinging on an ex-boyfriend, she didn’t know. Before she could ask, he disappeared into the back room, saying, “Ergo, as the world becomes ever more like a techno-jungle, we’re all searching for our next ping.”

How much more there was to her, she might’ve said, than Thad or any so-called ping. How much more than signing people in, directing them to bathrooms, and selling nail clippers or Do Good bars from the Grab-n-Go! Calculus problems from freshman year, various drawings, a Conrad Aiken poem she’d memorized (“Stars in the purple dusk above the rooftops/Pale in a saffron mist and seem to die”), all took a bow inside the private chamber of her soul. Excepting hot skirts or her father’s Lord, all manner of things engaged her. But did anyone notice?

Certainly Jean-Marie, the valet, noticed others in a fulsome way. One time, so deftly did he describe his grandfather, forced into a half-decade of World War II unpaid railroad labor when Burkina Faso was a French colony, she pictured the old man in her midst. Lithe as a ballet dancer himself, Jean-Marie presently was whisking open several doors of a monstrous SUV trembling outside the lobby. Each time the sliding glass doors parted, rich music could be heard popping from his throat as he circled the SUV’s girth, rumbling, “Welcome to the Gilmore.”

Apparently oblivious to his comic subtext, the passengers alighted, bore their way past him, and strode into the lobby, past Mr. Norris, now rolling his suitcase through his own echo before somnambulating onto the carpet that led to his room. Video-game style, other guests wandered more aimlessly, clutching phones, coffee cups, mostly in silence, except for one woman who’d lost her key. This time, with the air of a newly enlightened soul, rather than spout employee handbook lines, Jocelyn paid attention.

“That pink sweater is so becoming against your hair,” she oozed, touching her own rather haphazardly begotten pony-tail. But as soon as she’d checked the woman’s ID and zapped the blue rectangle that spelled “welcome” in formal script, the woman nodded, snatched the key, and disappeared with barely a grunt. Left fingering a stack of un-zapped keys, whose thick glaucous strokes recalled her Cezanne river, Jocelyn in turn felt bereft, or separated from a place she’d never visited, having been to Paris once and the French countryside not at all.

Shortly after that trip she’d begun work at the Gilmore, which rescued her from impecuniousness, not to mention her bickering parents and a crush of other job-seekers. But what about now, given an improved job market? Irritably, she looked around. Not unlike her ramshackle feelings, the lobby swung upward, outward, sheltering a tree, six fuchsia-colored chairs, one expensive rug on which dogs occasionally urinated, and three recycle bins she’d once cherished as symbols of corporate ecological concern. Yet now the walls seemed implacable, the décor antiseptic, the concern possibly dubious. Long ago the entire city burned to the ground, her great uncle often refrained, hence its surface vacuity, including spots city-wide named for landmarks elsewhere, like the unsightly Mount Vernon Highway, subdivision streets called Harvard or Dartmouth, and the adjacent Embassy Row Mall, as if only purloined memories resonated. And yet even those generated some measure of reality, albeit a fractured one. (“Are you adrift?” a guest’s leftover book queried on the back cover, and huskily she whispered, “yes.”)

After opening the book randomly, to encounter various civilizations that had depleted their soil, starting with Mesopotamia, she peered through the sliding doors, beyond the circular driveway, toward a brown patch appearing inert at first, then sparkly. A cluster of bushes had been plunked there by Landscaping, an ill-paid band of men armed with blowers who zoomed in and out on Thursdays. Surely, on her break, she might go out and explore further?

For now, however, a flock of statistics gathered in the next chapter pertaining to industrialized agriculture’s vicissitudes and she joined the breakfast crowd watching a TV goddess advise the multitudes to “inhabit the moment.” Best to use an app, the goddess proclaimed, shifting flawlessly in her green dress. Toward the chair of the Buddhist monk she was interviewing, she swung a cream-colored pump. The monk’s answers were soft, much softer than those of the breakfast crew straggling out waving jovial good-byes. As their voices rose and fell, Jocelyn waved back, almost tasting their joy at leaving work. Had she been promoted, their jokes and cadences would’ve dwindled into memories. Perhaps all was for the best?

Certain the orange-robed monk would concur, she glanced back at the TV to find his chair empty, the interview over. While several rapt faces in the lobby appeared mesmerized by his final remarks, she didn’t make enquiries, given her colleague Paulina reporting for work and her mind wearying. Courteous and hard-working, from Hungary originally, Paulina enhanced the behavior of everyone she encountered, including Jocelyn’s.

“Hi,” was all she said, but the word sailed through air on flotillas of meaning, given her multilingualism, her poise, and her blonde hair piled up winsomely. “Do any of you wish to take your break now?” asked she, as if the goddess had stepped out of the television.

“One of us better go upstairs,” Sean breathed, reminding them they were short-staffed as usual. “Room 411 complained; housekeeping is ‘slow’ today.”

“Isn’t that outside company in charge of housekeeping now?” Jocelyn asked, heading toward the elevator. As it whisked her upward, a puff of ambivalence escaped her gut. In the fourth floor’s twinkly gloom she stepped out to find two women fretting mid-hallway until, noticing Jocelyn they snapped into grins. “Hi, mees,” said one, whose face, the closer Jocelyn got, appeared to register fear, skepticism, and fatigue.

“How is everyone today? Carolina, Cathie—” How many times had she bristled hearing that faux jaunty tone from upper management, now—yikes—emerging from her own lips.

“Myrna says we gotta buy our own uniforms,” Carolina, who’d been there for years, blurted, referring to the formidable head of housekeeping. “For $41.99! We never have to before! I have gas, school supplies to buy!”

“I’m sorry,” Jocelyn sputtered, praying for Myrna to arrive and deliver her from her impotence. Never had she bought supplies for anyone but herself. Vaguely perusing Carolina’s bloodshot eyes, pudgy shoulders, she recalled her first employees’ entrance at a glamorous clothing store, where dinginess prevailed in contrast with the marble floors, chandeliers, and designer gowns out front. To transcend the dinginess, she’d learned to withhold parts of herself at work. If originally she’d believed those parts were in safekeeping, like chips clipped in a bag for freshness, now she wasn’t sure. Trifles, platitudes, were therefore all she could summon as she leaned against the wall, plucking three of Sean’s sprinkles from her left shoe.

Except for a faint flicking noise—Carolina yanking her fingernail—all was quiet until Myrna’s silhouette appeared beneath the neon-green EXIT sign. The flicking stopped; a suspenseful hush hung in the air. Myrna’s bulky figure shifted. “Hi Myrna,” said Jocelyn into the void.

“How are you,” Myrna murmured. “I need to speak to these ladies in the housekeepers’ lounge after they perfect this floor.” For Carolina’s benefit, she added a bit of Spanish, inducing the women to scatter as Jocelyn hustled toward her own exit. Once cloistered inside the stairwell, however, reveling in her escape, she conjured the lounge scene. Not that the fading gold vinyl sofa was so dreadful, but sharing it with Myrna might well be. Stained, curling around the edges, a pair of Federal notices about “break” and “minimum wage” tacked on the bulletin board might soothe, as would the elevator buzz and an aging Coke machine’s cheery hum; otherwise, the talk might be grim.

Downstairs, while a guest complained to Paulina about the dearth of parking spaces and Sean prepared guest cards to the pulsating rhythms of his dragon game, she thus slipped unnoticed toward her bag, zipped open her change purse, balancing its coin-heavy bottom in her palm, and yanked several bills gently, to prevent her credit card, driver’s license, from ripping them. Surely the wad exceeded eighty-four dollars? With a minivan group approaching—first a girl with sequin stars painted on her cheek, then a boy whose cheek boasted a snake—and no time to count, she jammed the wad in her pocket.

Just as she skedaddled, however, a tallish woman with curly hair and a strong chin loped toward the kids, who all nearly collided. “Where’s the restroom?” the woman demanded over the precious, unruly heads.

If Jocelyn had heard that question innumerable times before, it suddenly seemed ludicrous, reducing her chaotic self to an automaton serving others’ needs. And what about Cathie and Carolina, buying their own uniforms for the privilege of cleaning such a person’s toilet? “Around the corner, to your left,” she deadpanned, not like a service champ at all.

“DING!” Sean’s video game screamed, as the woman said to her companion, “So my brunch today SUCKED.” Mercifully, Jocelyn was headed in the opposite direction.

Up the stairwell she clattered, her stack heels echoing with a lonely rhythm, then tripped and regained herself before careening into the fourth floor hallway. Atop Carolina’s push cart she dropped several bills noiselessly in a plastic cup heavy with dimes, nickels, and pennies. After repeating the process for Cathie, she made a U-turn and rushed back downstairs.

“Do you take coupons?” a woman from the minivan was beseeching Paulina upon her return. Her entire group, dressed in catalogue sportswear, all tilted their heads toward the woman, apparently the unofficial boss, while the oldest man furtively mashed his baseball cap onto his head. “We’re here for graduation,” he said, yanking his jeans. “We want single beds.”

“Separate beds,” the bossy woman, presumably his wife concurred, as a van exploded on screen in the lobby. “My grandson is graduating with honors.”

“I’ve been roaming all over, and cannot find the bathroom. The service here is abysmal,” the guest whose brunch sucked declared. Flat and inquisitive as an out-of-tune instrument, her tone reverberated throughout the hallway. Hoping Sean would engage her, Jocelyn headed over to arrange Do Good Bars in the Grab-n-Go, while TV police investigated the explosion. Alas, the woman began scrutinizing not the TV but Jocelyn, whose usual answers, generally smooth, moist, and uniform, like ice cubes, didn’t emerge.

“I’m not your ice machine!” said she.

If poignant music wafting from the TV might have drowned out her tactless remark, she quickly surmised it hadn’t. With a tragic expression, a doleful head shake, the woman said, “This place has really deteriorated.” Jocelyn, ever cognizant of the SCOTT, monitored her eyelids for a hint of reciprocity, even rapprochement as the woman implored the air and riffled through her ecru leather bag. “Damn it—I forgot mascara!” she called, knuckles on left hip. To Jocelyn she became the epitome of every guest lacking spatial or situational awareness, fixated ad nauseum on immediate gratification.

Thus stirred by indignation, disinclined to suppress a hot force winding its way up from her gut, she said, “I’ll bet you’re one of those jokers who writes Yelp reviews!” All while clutching a bottle of violet air freshener. As if the aroma could perfume her words or prevent dismissal, she sprayed M&Ms, razors, Alka-Seltzer, peanuts, and instant mac-n-cheese, vaporizing the Grab-n-Go with a mawkish odor that wafted toward the lobby like a sad coda to a batty morning.

“Oh, God!” the woman coughed. “I have allergies,” she opined for the benefit of passersby, who assessed her, then Jocelyn in her navy blazer, name tag, and glaucous-colored barrette from the museum. (Certain its imprint, its sliver of a Renoir, connected her to art, to culture, perhaps even to France itself, she wore it often.) “She’s crazy!” the woman added, to sway onlookers, as Jocelyn flinched, wondering if the 24/7 cameras were installed. But happily, Paulina was approaching, murmuring with characteristic finesse.

“My apologies for the misunderstanding. Perhaps we can offer you a gift card, redeemable at our coffee bar?” As if it were a gift of state, she offered a golden rectangle.

Newly placated, the woman left, as Jocelyn squeaked, “Paulina? You’re so nice. You’re even nicer than a morning TV goddess.” She spoke concisely, because not only did Paulina handle guests well, she also attended nursing school online, often studying on the fly.

“People here are easier than my step-father, Jocie. Do you wish to take your break now?”

“Why not?” Gleefully Jocelyn plucked an orange from the basket, caught a stale whiff of pancakes midway through the lobby, and parted the electric doors. “Thanks, Paulina!” she said, the lobby doors flapping open and closed behind her, a final blast of A/C hovering. No matter how much her father disparaged air conditioning, to her it felt heavenly. But so did being outside, with warm air settling around her like a dome. Happily she fell back when Jean-Marie’s profile blew by in a guest’s Mercedes, palms and fingertips dandling the steering wheel, before he turned the corner, taillights flickering, then plunged into the garage.

“For real, Jim,” someone was saying, part of the breezeway’s ongoing dialogue. Festive as firecrackers, a cluster of ashes ignited, sparkled, and floated toward the sidewalk, while a shiny garbage can doubling as an ashtray embossed with the hotel logo caught a fraction.

“But what are the odds?” answered Jim, moving closer to improve his aim.

“Somebody won 8000 bucks this morning,” his companion rasped, as Jocelyn passed between them like a ghost.

Beyond the fifteen-minute parking spot she drifted, beyond the pullulating logo, which graced the awning, the van, even the laundry carts drying in the sun, and up a concrete slope that according to Thad once sprouted long-leaf pines. Especially today when facing a conundrum, she missed his anecdotes, his love for Carolina wrens, which inexplicably had shielded her from the sprawl now beginning to mar her breaktime.

Everywhere she looked, that is, steel buildings and generic florae prevailed. Hadn’t she once expected to remain at this job for no more than a year? If she’d been vigilant about grades—like Nadia, who did sit-ups every afternoon, citing acceptance rates for graduate public policy programs, while Jocelyn languished at the faux Acropolis, reading EM Forster, or books about ants, exchanging bons mots with other scofflaws not forming start-ups or aiming for med school—she’d be in grad school by now. A row of bushes, round and rigid as golf balls, seemed to corroborate this theory of her foolishness, while the shopping mall marquee flashed digital messages about its poke bar, now delivering through Uber Eats.

Between rows of cars, some parked, others idling, all puffing exhaust toward her knees and throat she navigated, while a flock of geese paced nearby, and a truck that said 100 calories of sheer yum rumbled uphill. From the hillcrest, diamonds glistened upon car roofs like unclasped necklaces lying flat, then faded near the squat mall several languid customers were approaching in the heat.

Happily the geese, impervious to ambient carbon dioxide, car radio talk, successfully crossed the road, then passed a jazzy acronym—ABX, in bright red—perched on a triptych-shaped wall engulfed by an office tower, the landscape’s only offering in the way of explanations or teleology, possibly designed to thwart questions altogether. In fact, even the way Jocelyn’s eyes settled on a row of yellow pansies planted in a triangle of soil felt predetermined. Maybe the same landscaping crew as the Gilmore’s?

Projecting vertigo, or vice-versa, she barely remembered her academic transcript, and the soil, which had inspired this foray in the first place. Within the span of a twenty minute break, that is, the landscape, seemed inscrutable, with genuine bugs or dirt almost non-existent. Also, Nadia’s numbers were dancing on her phone, just as she was wiggling out of her jacket, her bunched-up jacket sleeves sticking to her skin. Could she wiggle out of the dinner too? As if from another galaxy, the ringing curled into her ears as she dithered. Granted, Nadia, with her analyst job in nuclear disarmament, required her to think. “EG,” as Nadia would say, she jolted her from bathroom questions, not to mention her transcript. Quickly, Jocelyn pressed talk.

“Nadia?”

“Hi!”

“How are things?”

“Nervous,” she said, trilling the second syllable of the word. “I might be moderating a big conference in Vienna soon. On Iran. Kay Sanchez—she’s a law professor—said it could help.” Down a walkway toward the Gilmore’s green awning Jocelyn looped, nostalgic for cool air, while savoring the sky, blue as a crayon, crisp and pure as a child’s drawing. But no sooner had she uttered the word “sublime” than it fizzled into the cosmos.

“What?” Nadia said.

“Never mind. Help who? Iran?”

“My trajectory. Kay’s been commenting on NPR about the murder investigation, of the Iranian chemist. You haven’t heard?”

“Oh, sure. Worried to death.” Anyway: she’d look it up later. She sighed. Invariably Nadia’s chatter featured public events, famous names, or both.

“My colleagues and I—well, no one agrees on whether Ukraine is our biggest concern, Iran, China, some crazy rogue arms dealer—”

“Sometimes your life sounds like a movie,” Jocelyn said drowsily. Her remark was truncated; she might’ve added that occasionally she tired of being the audience. Closer to the hotel now, she focused on the smokers helping a minivan back into a lot that said: “fifteen-minute parking: all others TOWED at owner’s expense.” After one final breath the minivan shuddered.

“Anyway, just wanted to remind you: Nuclear/Cyber Risk Initiative tonight, Gautreaux Hall. Just look for the signs.”

“Initiation?”

“Initiative. Just come, okay? Wear your navy suit with the lime green trim. Gotta run!”

“Nadia, I just—“ But she’d already hung up.

There was nothing to do but show up later in her navy suit at a hotel ballroom downtown, near the university with which the think tank was affiliated. And what a contrast with the Gilmore! Inside the ballroom, golden tassel-fringed drapes and a white-linen bar sparkled beneath a ceiling crisscrossed with chandeliers. China trimmed in gold and blue, silver place settings, microphones, all awaited an illustrious panel, as did mingling guests, both inside and beyond the French doors opening onto a piazza. In fact, almost as if prizes awaited those who solved life’s riddle or at least chose well-connected interlocutors, the guests wove adroitly through the crowd, in contrast with the Gilmore, where behavior fluctuated.

And Nadia, if slightly oppressed by her purple skirt straining at the hips, meaning she’d hit Fowler’s bakery for brownies, a leftover high school jaunt, was adroit as anyone, mingling with grown-up aplomb. Full of social largesse, seemingly omniscient, she greeted a man sporting a red tie as another tapped her shoulder, all while summoning Jocelyn. Not wanting to cling, studiously involved with fetching wine, Jocelyn waved her away, deftly avoiding the fixed glare that had worked since they were thirteen.

“So you came,” a familiar voice interjected. It was Mason, Nadia’s boyfriend, whom she’d met twice before, and seen on TV reporting on cybersecurity and stocks. But so far they weren’t chummy. Although he wasn’t involved in Nadia’s tête-a-tête, they mostly exchanged fidgety glances.

“Yes, yes I did. Glad to be here.” Dazzled as anyone by his athlete’s physique and luminous blue eyes, Jocelyn couldn’t help recalling Nadia’s anecdotes, like the one about his Café Alsace outburst, when he’d bellowed, “I don’t know if I want kids; period.” But either way a resplendent Dierdre Dobson, also from News Channel Five, heading their way now, looked poised to intervene. After exchanging high-fives, she and Mason launched into TV style badinage, while because Deirdre was so famous Jocelyn said hello as if they’d already met.

“You’re Nadia’s high school friend, right?” Deirdre asked, shifting to the controlled manner she employed during the news.

“Yes, I’m Jocelyn. How are you?”

But no sooner had Deirdre placed Jocelyn than she narrowed her eyes and strained her neck to survey the crowd. “Great, thanks,” said she.

Wondering if she’d failed to be convivial Jocelyn loosened her shoulders like an Olympic swimmer, ready to try again. Only, Ted beat her to it, nudging Deirdre himself and saying, “Have you noticed Nadia’s a blonde now just like you?”

“Well, geez—“ Jocelyn began, then stopped. In fact, Nadia’s new hairdo did resemble Deirdre’s. Unless friends possessed eternal essences, her vision of Nadia might well be dated. “Geez,” she said again, mostly to herself.

“Oh, does that seem rude? Everyone’s rude to Deirdre and me when we’re interviewing,” Ted laughed good-naturedly as Jocelyn tried to think of a funny rejoinder.

But all over the piazza, cocktail noise swelled. Given the cacophony, nuances eluded her. When she dropped her keys on the floor and someone assisted she found herself gesturing with a gaggle of Taiwanese physicists distributing business cards and gracious smiles. At last she was escaping bathroom questions, even discussing quarks and the Higgs Bison with two who spoke English. Certain she’d languished at the hotel for too long, she ogled the precious cards. But when she turned around to ask why aside from Hitler et al physicists had dreamt up nukes in the first place, they were gone.

Or they were dispersing to find seats. Past handsome tables and a few remaining clusters of drinkers she wandered, scanning place-cards too. At one table, everyone erupted in howls after a fellow in a pink oxford shirt made a joke; self-consciously, she adjusted her skirt, before a prim white card embossed with her handwritten name jolted her. Four couples were eyeing each other warily as she sat down, soft damask grazing her arms. While the couples introduced themselves, her physicist friends dwindled across the room.

“And you’re with—“ interjected her neighbor, eyeliner-darkened eyes keen with expectation, blonde hair dramatically coiffed.

“I’m Jocelyn King.” The woman blinked; her lovely blonde spikes shivered as she nodded and assessed, then moved her knife a centimeter further from her plate. Was she relieved? “Cindy Jenkins,” was all she said. “We’ve been back here, oh all of twenty years; before that we were with the Clintons in DC.”

“You mean the Clinton administration?” Jocelyn queried.

“Yes indeed.”

“Did you enjoy Washington?”

“Loved it. So much to do—museums, parties—” her face brightened, “we lived in Georgetown, through the nineties and beyond.” Highly animated now, reliving her power days, she tapped the suited shoulder belonging to her husband, who turned around, obviously accustomed to well-wishers. “How do you do,” he rumbled absently, extending a chubby hand.

“Fine, thanks; you?” With middle-aged ease he smiled and chuckled. Happily sharing anecdotes about this club and that lawsuit, this gasbag and that great guy, he gestured with fleshy palms, as if to imply that in the end, life for those who survived was sugary. What a tonic! Soon enough, his frank whiff of exchanges and allusions to byzantine “deals” invigorated everyone at the table, while just beyond his convivial, grey head, Jocelyn spotted a wavy-haired man in the French delegation whose face didn’t suit a USA banquet at all. So arresting was his simple, aristocratic profile, so redolent of inner conflict and fine seriousness, even the golden drapes nearby looked meretricious in comparison.

Yet no one else, certainly not a group taking selfies nearby, seemed vexed by his grandeur. Should she bump into him, what to say? La fin du monde, if a bit extravagant, was one possibility—for conveying grief about the evening’s unthinkable theme, sans revealing her ineptness with French grammar. J’adore la France sounded trite, although she could add sympathetic references to inflation, street violence, and so on, unless she didn’t encounter him at all.

Besides, she’d come not to flirt but to find meaning, or a job now that HQ had denied a promotion. Worse yet, if the lady whose brunch sucked commented on Yelp or Reviews.com she could be fired. Thankfully, a quick website survey yielded—so far—no diatribes, although other specimens ranging from the trivial (“ewww— crappy soap bars, but NO foaming soap”) to the demented (“WTF can’t you idiots fix my personal safe lightbulb???”), reinforced the need for vigilance. Quickly, she closed the final website, imagining herself and the French ambassador in Montmartre. Then alighted on a memory of her college guidance counselor, Ms. Mendez, dispensing career tips to seniors, including her own arrogant 21-year-old self just before graduation. Bewildered by the premise, that others were to be of “use,” she’d recoiled from each stratagem—use social occasions to “network,” always carry digital cards, etcetera. Perhaps now she might change? For the benefit of her other dinner companion, she thus flashed a radiant, albeit professional smile, opportunistic and scruple-free. Demurely she gazed into her plate, then his, which faintly reflected a pleasant face, tiny ears, kind eyes, vast cheeks, and neck.

In a cotillion voice, he introduced himself (“Montel,” he exchanged for “Jocelyn”), cleared his throat, and said, “Forgive me. We just returned from Cambridge.”

“Britain or Massachusetts?”

Rather decorously he dabbed his lips, then rearranged his napkin in his lap. “The former.”

“Oh. Lovely.” Contentedly, she fingered her own napkin.

“It was truly amazing. I won a fellowship. Completed a Master’s in history, although, my paper, well, it’s difficult to bend chaos into a narrative, no?”

The woman next to him, presumably his wife given their shiny bands, rolled her eyes. “He procrastinated,” she interjected, then popped an olive into her mouth.

“What was your topic?”

“Ottoman Empire. Colonialism. Tribal incursions. Also the connection between the Ottomans and western imperialism, the West’s push toward the Atlantic as the Ottomans dominated the Mediterranean. And that’s only part of it.” His tone was scholarly, even elegiac.

“Fascinating!” she said, wishing she could cite specifics that would spill the empire, its languages, mosaics and fragmented history all over the table.

“In parts it’s non-linear; although I do rather cursorily address the region’s timeline, starting with the Eastern Roman Empire. From 480 AD to 700 AD Constantinople was the most sophisticated city in Europe. Of course Byzantine scholars preserved much of what we have in the way of classical manuscripts, as did Islamic and Jewish scholars, though so much was lost, like when the Mongols sacked Baghdad’s House of Wisdom in 1258. By the end of that century, the Ottomans emerged, and once they conquered Constantinople in 1453 they were dominant.”

“Have you visited the balcony of Europe? I saw a novel with that title once.” It was all she could think of; she hadn’t read the book, hadn’t been to Turkey, much less its balcony. As he nodded, other faces round the table shone with engagement. Someone mentioned the Kurds; then Armenians; another, Erdogan, eliciting groans; then everyone lamented the earthquake’s devastation they’d seen on the news.

Years ago, as it turned out, during her sophomore year in college, Cindy had semestered in Istanbul. “Did you ever visit the Blue Mosque?” she asked knowledgeably, the gold watch on her slender wrist glistening as she put her fork down to talk.

“On our honeymoon—” Montel’s wife said.

“Will you finish your doctorate?” asked someone else.

“Hopefully, in time. Although for now I’m with university development,” Montel shrugged, and everyone but Cindy’s husband shriveled. Because no one else wished to entertain that topic, a woman twisting her lips as if chewing limes, addressed Jocelyn. “Umm; did you just come here by yourself?”

“Yes,” Jocelyn said, purposefully monosyllabic, wary of what was coming.

“I would never do that,” the woman said, while others muttered thanks to deft hands serving plates of food all around. “Madison” the woman’s nametag announced in cursive.

Vaguely annoyed at serving as fodder for Madison’s insipid worldview, Jocelyn squirmed. Apparently, this milieu, like the Gilmore, featured dull and/ or rude folks too. “I guess you wouldn’t,” she managed to quip, before Montel and his wife followed up with vignettes about their three-year-old daughter, whose images preempted further inspection of Jocelyn’s personal life. Food dwindled on plates, dessert appeared, and before long, a breath hurtled through the microphone.

If no one knew why the Russian consul was speaking first, his purple tone like borscht, comic and passionate, as if networking in his world was an entirely different matter, briefly reshuffled everyone’s worldview. Like a jilted ex-lover guilty of the original transgression, he spewed about “America” and “the EU;” then pleaded for understanding. Or was he scolding? Former Russian states had been lured by NATO and the IMF, he charged. While Russia had gone to Syria legally, he couldn’t say the same for the US in Iraq, much less NATO’s forays. “What your problem is, you think you’re exceptional,” he said, gulping water lustily.

“But so is Russia. Also China. Lotta them, exceptional. Yet unlike America, we don’t impose our self-image everywhere. We never say ‘leader of the free world.’ We don’t have USA media tampering our brains,” he chuckled. His chin tripled; his tight shirt threatened to pop buttons. “Not stuck in Cold War thinking, we adhere to international law.” Deftly, or just dishonestly, he avoided Russia’s INF treaty violations and the treaty’s demise, also Putin’s brutality. “Russian casualties from World War II,” he chided, “26.6 million! You always forget!” Dimly, unable to fathom so many Russians, Jocelyn recalled muffled talk of her father’s uncle dying in that war, then their ancient mother, her great-grandmother in South Carolina, bravely, graciously, serving caramel cake, which tasted like sad sugar, the memory of which now caused her to miss the consul’s Ukraine musings.

Moreover, once he yielded the podium to Nadia’s boss, the former Secretary of State, whose lankiness and demeanor evoked both long leaf pines and those who had cleared them, without any sense of contradiction, all was forgotten. Order restored; war deeds and war dead a poignant but tidy symbol. Everyone at Jocelyn’s table sipped and nibbled, knowing the Secretary wouldn’t do anything crazy. Like an aria, names of sports teams circulated the room, then appreciation for co-workers, benefactors. Cindy’s husband beamed. Everyone hailed Ukraine. Eventually, in another tone, Iran and North Korea were cited, though not intemperately. Phrases like “new nuclear weapons states,” and “state-sponsored terrorism,” were launched and fired so quickly it was hard to discern if the Secretary had strayed from his aforementioned duality or no.

Another speaker, a newish Congresswoman, wasn’t so understated. No matter the cost, she said, Russia must be crushed. Ditto, China. If Putin won in Ukraine, he’d continue, as would the CCP. But not to worry; sanctions, the rules-based international order, would redeem all. As would weapons flowing into Ukraine. Not to mention, Russia might change regimes, leading possibly to unsecured nuclear materials, but only temporarily. Sagging in his chair, possibly trying to remain honorable, Secretary Lambert looked weary instead, his homely old-fashioned face tottering. Apparently, as Nadia had warned, bigger things than her job or even grad school, were “transpiring” as she’d put it, professional journal-style. Thus reminded of empires, arms deals, and historical epochs Jocelyn’s face congealed, though not for long, because after all she had to proceed, no matter how trite her problems.

Which were what? For her, a bad internet review. How about her fish—was it really Alaskan? Salmon? An unseen pattern of supply chain issues, ecological flux, fuel prices, trade regulations, ocean pollution, and pop-up wars, all requiring expertise, all underpinning the answer, might delay supper if botched or, God forbid, cancel fish altogether. About each subject she knew little. Yet acquiring an expertise would leave less time for sipping cappuccino at the registration desk, absorbing universal vibes. (Or vapors, Nadia might joke.) Ha! If she continued like that, however, time still would unspool, eventually into thin air. Pityingly, but charitably, she glanced at Cindy, Montel, even Madison, all past twenty-four, then at Nadia, so convivial with her colleagues, still vibrant as she was in high school.

“’God, I’m sophisticated,’” Nadia used to chant in the drollest tone a tenth-grader could muster, upon finishing Gatsby. Back then, Nadia’s father often shuttled them to high school in his Lexus, assessing women if Nadia’s mom wasn’t present. Declaring he liked them “smart,” he’d analyze a random employee, her abilities, looks, whether she’d been “close to her father,” etcetera, narrating, he implied, from a perspective incomprehensible to mere teens. Because her own dad was a pastor, she’d credited Mr. Becker with real world savvy. As did Nadia: to placate him she was studying economics, she confided one night in college, holding over Jocelyn’s Biology worksheet a cheesy pizza slice, whose goo dropped with a tomatoey splat. Hilariously scrubbing a damaged paragraph, Nadia rattled off names like “Keynes, Stiglitz, and Bernanke,” as the page turned pink and fuzzy.

Jocelyn sighed, wondering if the French delegate would be less boorish than Nadia’s father, or various hotel guests. Meanwhile a physicist at the lectern recommended vigilance with regard to cybersecurity threats posed by non-state actors and private military companies. Yet he also cited hopeful statistics; from roughly 1996 to 2016, for example, the energy powering one in eight USA lightbulbs came from recycled Russian nuclear bombs. Eureka! As the audience nibbled chocolate torte, an ex-Senator, Secretary of Defense, and two movie stars were credited with executing the plan.

In fact, one of the stars who happened to be in the audience, sporting a familiar grin, popped up to acknowledge an ovation. A frisson encircled the room; he waved mechanically. But according to the professor, eight countries in addition to the US still possessed nukes: Russia, China, Great Britain, Pakistan, India, France, Israel, and North Korea. Russia, he sighed, might use them. Other, smaller countries might procure their own. Still, the symposium took on a festive air. All around, everyone reveled in his or her beautiful importance. Jocelyn, too, basked in their eminence. Wouldn’t it be heaven to be on the podium, predicting security threats, the transformation of bombs into energy, using precise, au courant jargon? Yet who would listen during Q & A to a young woman prefacing her Q with, “I’m Jocelyn King, with Gilmore Hotel’s registration desk?” It occurred to her that the relief in Cindy’s eyes when she sat down had been her assurance that Jocelyn didn’t count. Apparently she wasn’t the only one seeking a validation-ping from some lord of the techno-jungle.

Ergo, for imaginary support, she checked the Frenchman’s chair, which was empty. And then stood, bruised about not counting, disinclined to parse another lecture. Besides, she had to get up early; although on her way out might she possibly bump into the Frenchman?

Past innumerable flushed faces and clapping hands she scuttled, past the physicists, then a table of donors in expensive suits, their damask napkins tossed carelessly on the table, wine glasses stained with lipstick or traces of Burgundy, waiting to be whisked away. On her face she bore an expression of faux humility, as if accepting an Oscar. Sensing footsteps behind her, wondering if the Frenchman, or Brad Pitt, wished to discuss the environment, she pivoted.

“Where are you going?” It was Nadia. Magnificent in her purple suit and flat, low cut shoes, her glasses and peek-a-boo camisole, she exuded passion. In fact, with the crowd still clapping, she evoked the Statue of Freedom, or Joan of Arc. Given a State Department official stepping up to lecture next, Jocelyn felt obscure and buffeted as an Estonian delegate who scooted out behind them, prompting Nadia to bid him good-night in Estonian. It was the most prosperous of the former Soviet republics, she whispered.

“Bye, y’all,” he responded as they landed in the hallway, his suitcase prongs scraping marble, wheels hitting the floor, before he tapped down the hall and Nadia reverted to her less charming voice. “Where are you going?”

“Home.”

“What about the Q&A?”

“I’m tired. Probably neither Q nor A will resolve things. Besides, if the world ends tonight, I can sleep later.”

“Oh, great, Jocelyn; guess what?— FYI, some things in life are serious.”

“And you’re always addressing them, aren’t you? You never dwell on the mundane. Maybe that’s why Oppenheimer—and the others—developed bombs, because they couldn’t stand the mundane!” Unabashed by generalizations, she looked around, gnarled with her own passion, yet eager to avoid a nuanced debate, which would require actual knowledge of, say, uranium enrichment or INF treaties.

“Oh, that’s so-o-o-o deep. So sophomore year, three a.m,” Nadia said. “Would you care to hear our nuclear non-proliferation strategist’s view, or the International Atomic Energy Agency’s?” The speaker, his cadences still audible advocated a global panel on AI; also a climate refugee plan. But there was good news: Kazakhstan had removed spent nuclear fuel from its aging Soviet reactors. Last autumn Yale had beaten Harvard in football.

Duly riveted by all the crises, Jocelyn, deciding she’d been sophomoric indeed, almost gave up. But instead sputtered, “Of course. What do I know? But that’s part of the problem—everyone in a frenzy promoting themselves, just like an escalation into war.” Her awkward words landed with a clap.

“Well, duh, Jocelyn; there are wars going on. And potential wars. Ever heard of Taiwan?”

“I’m not referring to that; I’m referring to us. Here. I don’t see a war outside; do you?”

Several mirrors caught her and Nadia together, their friendship, not to mention her high hopes for the dinner, fracturing. Oddly, the scene reminded her of slogging through her college snack bar job junior year. Lifting syrup cartons to replenish the soda machine, she’d see reflected in its ancient silver panels mostly sorority girls’ faces, then their beaus, awaiting their turn boisterously or laconically, but either way resembling fragmented mannequins in khakis and expensive shirts as she turned around to serve Cokes in a blur. Presently, Nadia would appear, a friendly face, chubby back then. After serving her, Jocelyn would turn back and admire her own hazel eyes, sure she and Nadia would transcend the entire scene. If Nadia had, why hadn’t she?

Outside, hydrangeas, azaleas appeared and then vanished as she strolled behind a hedge, until a serpentine garden lined with bulbs illuminated a path into the garage. A pretty maze, but no answer; plus no sign of the Frenchman, who probably had been ferried away by a driver. Which meant she wouldn’t be sipping wine at a bistro discussing Lavoisier, but heading to her condo bearing no resemblance to its namesake except for the front gate’s fleur-de-lis emblem and a Mirror Pool replica where vapers went to vape.

“Trust me, Sean; is that your name? You don’t want to make me late for my fucking flight,” a hotel guest was saying early the next morning when she arrived at work. Rather menacingly, he leaned over the desk, three golden drops of syrup clinging to his shirt pocket, as other patrons streamed out of the elevator, the signal resounding like church bells. After the man left, Sean groaned, while Jocelyn aimed her best employee handbook smile at everyone, including Mr. Norris, who glided past Registration, relaying Padres scores into his earbuds.

“Everything okay?” she asked Sean during a respite.

“It’s the three-month anniversary of Mother’s death.” After an apparent overnight shave his cheeks and neck looked soft as pudding beneath the eco-lamps. “I miss her so much.” On his jaw two pink spots wiggled.

“I’m really sorry,” she said, taking in his latest manifestation, aware too of her own protean self. After the dinner she’d slept fitfully, burdened by the lecturers’ insights, then awakened feeling prickly, as if she’d been stung by wasps.

“Make sure you don’t drink from too many plastic cups, okay Jocie?—they increase estrogen. My mom said that’s how she got cancer.” Sean motioned toward her coffee cup. “And FYI, I’ll text if it looks like you’re fired. Or check Yelp. It’s a techno-jungle out there, Jocie.”

“Jeez; can’t I entertain one danger at a time?”

“You just need to be aware of potential issues.”

“From whom? Mismanagement? Giant hotel bed bugs?” she asked nonsensically, lightening up because it was almost her day off. But another voice hissed from the Grab-n-Go.

“Mees? It’s me, Carolina.” She beamed. “Cathie took the money.”

“From your cup?”

Urgent nod.

“Yesterday?”

“Mmm hmm.” Carolina put down her Red Bull.

“Not just her half? From her cup?”

“Mucho. All of it.”

“Did you ask about it?”

“Nooo, no way, José; she might call police about me.”

She didn’t know what Carolina meant. Too, she didn’t know Spanish. Motioning and gesturing ended; they both threw up their hands and laughed. As she’d stopped at the ATM that morning thinking of her day off, she could offer forty-two more dollars, which Carolina instantly received with her many-ringed fingers. “Thank you mees. Gracias. I will bring cookies for you. Butterscotch: made by my niece. I thank God for you. You spend the day off by yourself?”

Aghast that God could be summoned over forty-two dollars, Jocelyn nodded. Already she was anticipating a brief idyll outside in Jean-Pierre’s company.

The air felt clear, and he greeted her warmly. “Bonjour, Mademoiselle!”

“Bonjour Jean Pierre!” As always, she basked in his joyfulness, so often tinged with fortitude and solemnity.

“Comment ça va?” Ridding the driveway of dried leaves, his baggy clothes swinging from his taut physique, he whisked the broom around, practically dancing, saner than anyone.

“Très bien,” she said, yearning to dance too.

“You know, back home,” said he, “there’s a custom. When a man is ready to be married, the older man take him into the bush for a month, teach him to be a husband.” Swish, swish, he kept sweeping, neglecting to clarify his own status, although their conversations often were ephemeral, like pausing in a train station with someone who might vanish anytime. Presently, for example, a minivan was nosing its way into the unloading area.

“À bientôt!” he said, flashing eyes, generosity, and spirit her way while hastening to fulfill his duties.

Like a chasm the day opened before her as she checked emails in her car. “Enrich your banking relationship,” the first importuned, offering credit lines galore as pop songs blared through her speakers. For a nondescript mile, she coasted cheerily. After a few miles, even as the city’s density thinned, one strip mall after another kept appearing, until she burst onto the dingiest specimen’s mottled lot. Inside Meet A Pita a chatty lady standing ahead of her beneath the “Already Ordered Online” sign queried the middle-aged owner as he bagged her falafel wraps. “Are you from Iraq?”

“Moi?” With a jaded, jovial look in his eyes, he offered an exhausted, dollar grin. “I’m a citizen of Lowe’s Shopping Plaza.” Rather ecstatically he enunciated his three final words while tilting his overloaded cash tray, causing everyone, including a demure woman in back dropping hummus into Styrofoam, to giggle. “No country for me. Okay? Iraq who?”

Above his head, two TV journalists extolled the US president’s marriage, then analyzed the itinerary of a private military firm’s CEO. Up through Somalia, Yemen, Turkey, down through Italy, a computerized red line zigzagged across the screen, until an invisible narrator conjectured that he’d bought himself a Mediterranean island with arms deal profits. Clutching her sandwich as if it were a sacramental meal, Jocelyn wound around a man in a Star Wars T-shirt, then a grey-suited lady, both riveted to their phones before she exited.

Already queasy about fissile material, plus the TV’s eerie characterization of the world as mercenary paradise, she set the damp, vinegary wrapper on her passenger’s seat tentatively. Along a mute stretch of undulating and shimmering road she drove, fast food joints’ short snappy names growing so redundant her eyes darted and scanned as if to defy them. Intermittently, her mind thrummed with fear and minutiae. Surely, she consoled herself, a pizazz-requiring world-class arms dealer wouldn’t show up here, nor even in the quainter suburb she was entering, which according to City magazine was experiencing a “renaissance.”

At the very next light, a stylish row of shops appeared. In the first window, monogrammed beach bags lining the floor encircled party invitations stacked into a pyramid, flanked by languid mannequins wearing colorful prints. Tiny giraffes, sailboats, and pink petals flecked tunics and shorts. Worn by certain Gilmore guests whose fancy cars Jean-Marie drove with special, if mocking, care, for Jocelyn they evoked unfathomable leisure.

Quickly, she turned left when a brown marker signaled entrance to a park featured in City’s article. Her windows down, she savored the breeze, then a column of oaks emitting a musical hush before a half-circular parking lot appeared.

A rope climbing dome, a gaggle of children clambering up the lattice, all were familiar from the magazine as she headed toward a grown up swing overlooking a cavern, whose silvery water flashed and gleamed in the light. Careful not to miss the elusive seat she sat down, but no sooner had she arranged her sandwich than her napkins fluttered. Like a wine-sipping movie character, she creaked back and forth after fetching. But what next? In the movie, perhaps banal dialogue or violence, none of which appealed. Up close, the river looked flat, almost as flat as the Gilmore’s lake, its hue shifting from gray to brown as she pulled lettuce shreds dripping with raspberry vinegar from her sandwich and dangled them over her tongue until a tartness stung her eyes.

With sunlight intensifying, she moved to the swing’s shadier corner, her vinegary fingers sticking to the metal, and given the glare, outlined and filled in with crayon eyes the trees’ silvery trunks. Of course; they were sycamores! In honor of their taciturn dignity, she rocked to and fro, no longer summoning movies. Neither futuristic steel, nor a brand, nor any guest intercepted her thoughts. Yet the other trees were strangers. Gradually, the sun’s caprices evoked time’s quiet rhythm, and peacefulness ebbed. Solitude, as it turned out, could befuddle as well as liberate; but happily, Nadia buzzed and redirected her thoughts.

“Miles said I wrote something “not up to par.” I’m thinking he’s depending more on Marilyn now,” she blurted just as Jocelyn was saying, “Nadia?”

“What? Oh, I’m sorry.” Across the field, two boys leapt from soaring swings and landed in a raucous heap on the ground.

“Marilyn is younger, already has graduate degrees in environmental science and nuclear cyber-security, published her thesis on nuclear cyber-security—”

“Why do you care so much what he says? You have a master’s—“

“I heard him say so on the phone. ‘Marilyn has done more for the nuclear risk initiative in the short amount of time she’s been with us’—“

“So what?” To hear that nuclear experts could be petty as hotel guests was most disturbing. As was hearing that Nadia, with her golden resumé, imagined it wasn’t enough, that life itself was an arms race.

“It’s LIFE for me!” Nadia screamed. “I don’t want to—underperform. Marilyn is up for a State Department job! If I moderate this conference about Iran in Vienna—“

“Iran is partly our own fault; it’s not just Khamenei, or Ahmadinejad. We helped the Shah,” said Jocelyn, pleased to display her newfound sophistication.

“Well, duh, Jocelyn.”

“Besides, what’s the point of fighting nukes if you don’t treasure—existence?” she sputtered, attempting to translate the ineffable she’d gleaned from the trees. (Although how disconcerting to sound like her father, exalting meekness and the daintier virtues.)

“’Treasure existence?’” Nadia mocked. “It’s competitive out there, Jocelyn. I can’t just live day to day like you! Without any—“

“What?”

“Any—“

“What?”

In the course of waiting, her phone dimmed. Glowing one minute, inert the next; a spasm and a little death. Pity, because she’d had her response ready. It wasn’t that she favored nuclear bombs, but she wished to savor, well—she looked around—nature! Surely that was the Nuclear/ Cyber Initiative’s ultimate reference point, unless it was the aforementioned ineffable. Meaning what? Defiantly, she looked around; grass and trees shrugged. And FYI— was that a beetle crawling up her leg, or a tick? A tick could inflict Lyme disease, her father occasionally relayed, CDC-style. Instantly, she hopped up and flicked it away, then rubbed knees and ears, writhing, until a crumbling, pre-card key era chimney came into view. According to a nearby historical marker, the chimney was the sole remnant of an 1840 house whose owner had died, leaving a wife, nine kids, and a ferry to run. Implicitly upbraided by such an ordeal, also the raised letters, she straightened her shoulders respectfully. Although, circa 1840, hadn’t Cherokees still lived north of the river, the Creeks due west, just before the Trail of Tears?

No one answered. Across the field, a ghostly crescendo swirling around the climbing dome, the swing set, and the jungle gym, intermingled with children’s singsongs and their parents’ lower octaves. A juxtaposition of noise and silence vibrated aloft as if an eerie ambiguity prevailed. Impulsively, she rang Nadia back. “Why do you think you’re all so brilliant anyway?” she blurted, unable to think of anything else.

“What?”

“Why do you—“

“I hate people who don’t do anything about life. Like my mother. She’s still saying, ‘Mmm, what can you do.’”

“Well I hate people who never allow their toenail polish to peel. And post-apocalyptic films.”

“Toenails? Movies? That’s what you think about now?”

“Well, why are movies so full of plots and explosions? If everything’s fine except for nukes, why such meanness? And egotism.”

“You should know. Maybe you’re referring to your hotel lobby?”

“Well that’s a cheap shot.”

“Fine; then where are these allegedly egotistical films and toenails to be found?”

“Everywhere! At the hotel, at your dinner. Weren’t a gazillion people killed in Rwanda without nukes? Or how about Pol Pot? No one at your dinner mentioned him.” Unsure whether this was disingenuous, she felt proud, summoning AP World History.

“How does Cambodia pertain to our dinner?”

“Your guests sounded so wise, like life is so rational. With the latest gadgets and a policy tweak here and there, they’ll prescribe solutions. Whether they believe the world is that simple or they are, I couldn’t tell.”

“Well, I only invited you because—you’re in a rut.”

“But you listen to people like Dierdre Dobson. And Mason.”

“Well, they’re well-informed; they don’t rant.”

“Well; at least I know I don’t know.”

“Oh Lord. When did you become so overwrought?”

“When did you start using words like ‘overwrought,’ to describe a friend?”

“Ugh! I’ve got people waiting.”

“So do I.”

“Okey-doke, Jocelyn: ciao.”

When had Nadia begun saying “ciao?” In truth, no one was waiting for Jocelyn. But near the park entrance she’d spotted three horses, one white, two chestnut, their crests bent toward earth, noses vanishing into green plumes. And beyond them a red barn, its clean lines etched into the landscape, captivating like a dream. Plus a phone number, which she’d kept. A ride might quell her anxiety, or at least prevent her making inane calls. Before she could entertain doubts, a woman answered. “Crabapple Stables?”

“Uh, hello, how are you? This is Jocelyn King, I—wonder if you do trail rides.”

“Well, for birthday parties. You throwing a party?”

“No, I’m calling—for me—”

“Well, it’s just me and the ponies right now.”

How long had it been since she’d flung her leg over a saddle, inhaling barn odors? A glimpse of roosters, hay, the aroma of leather saddles, all mingled into a current that burst through her veins, eliciting faint traces of desire. On the trail, the scent persisted, like an ancient melody circling the branches, though she didn’t recall ever feeling so precarious atop a horse. For balance, she pressed the balls of her feet against the stirrups.

“Whenever corporate people come out here,” her guide, Molly, riding a horse named Jeb said, “it’s a jolt. You remember actinomycetes don’t you? Cause of the soil’s aroma? Hey, is that a Red-shouldered Hawk?”

With uncanny ease, a beatific expression, Molly glided into a trot as if aiming to fly alongside the bird. Heaving upward in turn, Jocelyn’s horse, Rita, stunned Jocelyn who stunned herself posting, albeit more moderately than Molly thanks to Rita’s smooth gait. The hawk skimmed earth then rose and soared into the sky, which appeared to lift with his ascent, like a courtship with infinity. What a thrill! Nonetheless, Jocelyn monitored Molly’s Bermuda shorts and slouchy flannel shirt for signs she might canter, until the bird vanished and they shimmied up a short, steep incline, mercifully unsuitable for cantering. Atop the hill through exquisite greenery, blighted only by a nearby thicket studded with plastic and beer bottles, they wound delicately. Reminded of the plastic cups and hotel cards in her back seat, Jocelyn winced, then looked ahead.

And not a moment too soon, given Molly pulling her reins at a kiosk. Quickly, lest Rita plough into Jeb’s bottom, Jocelyn pulled hers. Clasping the soft leather straps in her left hand, placing her right on Rita’s mane, she cherished the large soulful eye turning her way, stroked her long silky neck, and glanced at the kiosk. In a laminated 1902 newspaper article a lawyer, plus two businessmen, were pictured negotiating with a Philadelphia investor to build a hydroelectric dam nearby. Given their stately demeanors, the men looked startled by the camera, perhaps unable to foresee the arbitrary images, lights, and 24/7 monitoring that would ensue, plus the stale grins their descendants would offer LED bulbs, possibly rendering their gravitas obsolete. But thanks to a one-sided contract. her great uncle would’ve groused, the city lit up.

With Rita’s forbearance, Jocelyn leaned closer. One man, the lawyer, whose sinewy physique looked familiar, was Thad’s great-great-grandfather. If he’d worn a baseball cap instead of a fedora she might’ve mistaken him for his descendant. Yet he looked elegant, more circumspect than Thad, whose boasting about the country club his forbear founded and the university he’d endowed, had perplexed her.

“There’s the dam they built over there, first hydroelectric plant in the state—circa 1904. It strangles the ecosystem,” Molly gestured. “If not for that, minerals, rocks, would be flowing toward the coastal plain, slowly transformed into millions of grains of sand.” Not wearing a helmet, she shook her splendidly unkempt hair, highlighting eyes so acute their final object seemed, paradoxically, faraway. “Originally built for the street car line, it now serves four thousand homes. And for the future”—with her left hand she put air quotes around “future” — “the company’s building an over-budget nuclear plant, plus wind turbines. You might say,” she pivoted effortlessly in her saddle, “I’m ambivalent.”

Oak leaves trembled and whispered, a breeze lingered, and the horses resumed walking. If Molly’s intense watchfulness anointed each and every tree with meaning, Jocelyn still identified very few. Lacy branches, dappled leaves, air, and light, past and present were all she saw, employing a bit of mysticism, too few details. Yet one detail was clear: she’d decided about life too soon. Fixating on minutiae, or defining herself in relation to Thad’s family, Nadia, the Gilmore, even the Holy Ghost et al, she’d narrowed herself. Or neglected to meditate?

Pressing against stirrups, sinking her hips into the saddle, she inhaled and exhaled, then forgot. Notwithstanding TV goddesses’ advice, that is, respiratory awareness yielded to images, say, from Nadia’s dinner—damask napkins, Cindy, her husband, the Frenchman, and the speakers—non-meditative though they might be. Those in turn evoked mages of her trip to France, when a tour guide quipped that her once-goofy brother was now a top executive for France’s nuclear power industry, often causing her to wonder.

“Just think: Around the time they built the dam, Cezanne painted his last river, later the scene of two World War One battles. And Einstein submitted his paper on general relativity.” If she couldn’t match Molly in ecology, warmed-over non sequiturs from her senior thesis on “pre-World War I culture” might do. “Of course some people give Poincaré credit for relativity,” she added, being a Francophile and all.

“Well, the dam messed up everything. The river, the ecosystem, the flow. Think of middle-school geology; that alone explains what a phenom this place is. After eons of time, a supercontinent breaks apart, then the smaller continents collide: And eventually voilà, you have crystalline rock, metamorphic volcanic rock, granite: rock formations so powerful the river gradually swings toward the southwest.”

None of this followed Jocelyn’s remarks, which admittedly had been out of the blue as well. “You were aware enough in middle school to remember all that?”

“I was the kid with pet turtles, a lizard named Zeke; I was in pony club. Hey look! That’s a bald eagle. Hot damn!” Molly whooped. As with the red hawk, in tandem with a fellow creature her whole body shivered. Ecstatically, she thrust her fingers upward, while Jocelyn with some engagement but less immediacy watched his silhouette glide over water, wings flaring. In the majestic way light shifted over an array of purple flowers scattered up and down the hill as the bird swooped upwards, awe rippled everywhere. Then it fled: the eagle soared into the empyrean, dwindling into a child’s scrawl, as the riders plodded on the dirt path below.

“Native Americans thought bald eagles were messengers sent from the other world to ours,” Molly whispered anon. “Did you catch those purple asters?”

Scraping her helmet as she ducked beneath a low branch, touched by Molly’s openness, Jocelyn fluttered, neglecting to answer. “This is one of the coolest things I’ve ever done!”

“What?”

“I’ve—hidden too much.”

“From what?” Molly asked, still searching the landscape. Apparently, notwithstanding her focus on one patch of ground Molly, unlike Nadia incidentally, was receptive.

“Maybe when someone close to me died, when I was seventeen, I hid, but that sounds so logical, like a facile test answer. So, maybe unclear. Like in college I always thought some subjects were more intricate than they seemed. And overlapping.” Charmed by her own profundity, she elaborated. “Like in botany: as kids we were offered a classic leaf diagram, yes? But the leaf’s richness, its protective bacterial cover, and the leaf’s, uh, internal endophytic fungi, went unmentioned.” No longer bound to the SCOTT, she rejoiced at each of her notions, albeit in the leaf’s case, one purloined from the departed guest’s soil book.

“There’s a similar problem with hydropower dams, which, contrary to received opinion, increase greenhouse gases and cause a host of other problems. What a pity other countries keep building them.”

“I was wondering why the river looked so flat,” Jocelyn said, unsure if a media-style villain was involved, human machinations à la her father’s sermons, or none of the above. If she’d retreated into a metaphorical hotel room, viewing the world through an aperture, vitality cascaded through her bones now. “I’ve been thinking of applying to grad school, to learn more, but sometimes it seems even the well-educated barely talk—or listen.”

“Yeah, I grew up in Washington, in D.C., and everyone in my family is a big achiever. Private schools, top colleges, lacrosse, and they’re a mess.”

Instantly Jocelyn bore a ponderous expression, as if for too long she’d left sundry, perhaps gnostic conclusions unaired. “When I graduated college, we kept filing on stage to receive our diplomas as the chancellor robotically shook everyone’s hand, until a billionaire’s daughter appeared and he bowed and kissed her cheek. Really, it wasn’t her fault; she was nice, even somewhat melancholy. Now that I’ve worked a registration desk, I think I understand why he did that.”

“Hmm?”

“People can be flimsy. Or focused on themselves, trapped in a box. But I have a friend who actually works for peace.” When convenient, she wasn’t above boasting about Nadia. “She works on making sure all this doesn’t get blown up.” Vaguely, proudly, she swiped the air, then guided her horse to follow Jeb, whose tail swished when Molly tweaked her reins and veered toward another path winding through the woods.

“Let’s go up here. Since you like it so much, my husband has a condo opportunity he’d love to show you. Our plan is to lobby the power company as a community to reform the dam. Oppose development and construction run-off. Bo grew up around here; he knows all about developers.”

Jocelyn stared at Molly’s enigmatic head, her brown hair still charmingly askew. “We don’t wanna be hooked on corporate America,” she was saying, as the afternoon’s gifts faded. (All Molly wanted was to sell a condo?) There was nothing to do but lean forward as Rita scrambled up the hill. At the top Molly was pointing. “There’s the house we’re renovating, and dividing into condos. Way up here, the river looks idyllic, yes? No runoff, no fertilizer in sight. And up there you can see a rivulet beyond the house.”

Jocelyn didn’t bother to gaze across the river at the ramshackle house, whose future condos she couldn’t afford. Though what a gorgeous view! On the embankment, trees—again, hickories—soil, and water bent into the light and appeared to melt together in the glare, while on the rivulet, a few white tips appeared serene for an instant, then curled inward and vanished, forming tufts that swirled and eddied, now caramel, then gray, beneath a sun engaged in a pas de deux with the clouds. Rock formations spoke with ancient tongues—Precambrian and Paleozoic, according to Molly, who had switched to condo interiors and amenities.

“Everything’ll be eco-friendly. On one side, residents will have views of the hollies. They’re originals: on that hill, no way loggers could reach them. Did you know piano keys come from hollies?”

Nope she didn’t. Like her dad with his vainer congregants, Jocelyn wilted. A nameless Mozart piano concerto, the rivulet, bald eagle, Thad’s great-great grandfather, plastic, even the solidity of Rita’s hooves mashing into earth, all collided in her mind while Molly chatted. “Dams even change the water’s chemical composition, thwarting minerals that usually flow toward the estuary. To live, we’ve tried soil erosion, logging, coal, hydroelectric dams, maybe hydrogen soon, obviously nuclear, and still haven’t nailed it. But the magic of this place is palpable for me.”

Twisted by wind, hydration, and glare, branches and leaves pressed close in a kind of wordless glory as Jocelyn listened, heading downhill toward the clearing, where a sliver of red barn awaited, expanding and bobbing in the distance. “Do you know anything about the Cherokees?”

“Up the river there’s a marker,” said Molly.