Lady MacDuff’s Castle: A Meditation

Whither shall I fly? / I have done no harm.”

What might be a near-idyllic brief scene between Lady Macduff and her very young son is shadowed even prior to its culmination by tension and uncertainty. In her husband’s absence and before a messenger warns of danger, Lady Macduff feels anxious and abandoned. Her son shows a precocious skepticism: Who are the traitors? Who are the honest men?

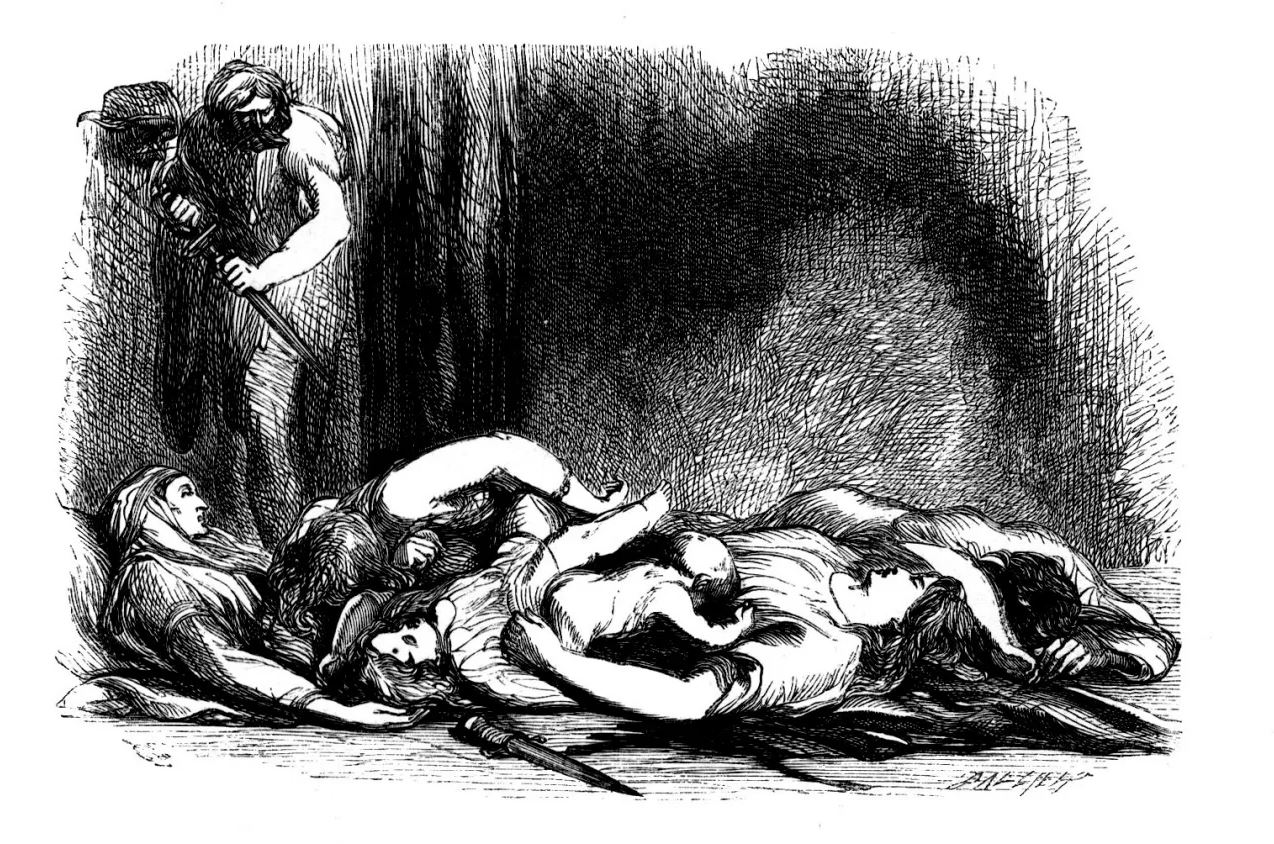

We find unrest, anxiety and doubt where there ought to be simple assurance and safety. Tender, innocent banter and the lightness that should accompany it are compromised and short-lived. It is the doom of the privilege of unthreatened life—what Scotland itself stands to lose. A messenger with his warning to flee dangers imminent and extreme is closely followed by the entry of assassins. Lady Macduff’s young son is murdered in front of her: “They have killed me. / Fly, mother.” She herself and the younger children (off stage) are next.

Except for Lady Macduff’s despairing outcry—“Whither shall I fly? I have done no harm”—the language is not memorable. It is poetically unembellished. The intensity is in the facts.

The event will be conveyed to Macduff, personal grief and outrage converging with his fealty on his country’s behalf. But it also remains essential that we the audience witness, live through, this scene: distress has entered here, nothing in daily life is safe. Each moment, each gesture, carries with it the likelihood of harm. The murders in Lady Macduff’s castle are among Macbeth’s most gratuitous—brutal and savage as they are futile.

Macbeth is aware that Macduff (his real target: the witches warned “Beware Macduff”) is away in England and that Macduff’s progeny are no eventual threat to his throne. He intends to have “firstling” thoughts and deeds accompany one another. Are these most base of murders a mere display of spontaneity? Or can it be that just after the witches have shown him a long line of successive kings through Banquo’s son Fleance who escaped assassination, a severe tension is created, discharged by targeting surrogate progeny? The very young Macduff children are surrogates. Here is a desperate, unavailing assault on the continuity of life itself. Nothing is safe from harm or distortion.

Mourning and elegy themselves are aborted, curtailed. Macduff will repeat—“My wife, too, did you say all?” His partial knell is broken by shock. Macduff’s grief-struck avenger’s deep resolve undergoes its sombre convergence with his country’s cause.

Psychologically, dramatically, madness or void come close to the habitat of the Macbeths. “The Thane of Fife had a wife. / Where is she now?” Mad Lady Macbeth registers this death along with those of King Duncan and Banquo. Macbeth responds to the news of his wife’s death: “She should have died hereafter. / There would have been a time for such a word.”

Macbeth and Lady Macbeth are themselves tormented by the pervasive evil they have created and sought to perpetuate. They are not quite to be dispensed with by “butcher and his fiend-like queen.” They are not Iago. They are human enough to suffer unforgettably but without the soul that might render suffering redemptive.

Scotland itself, like a thoroughly wounded agent, will require help from the English king who has the gift of healing as well as thousands of soldiers. Nature too will take part: the boughs of Birnam Forest.