Meditation on Time

by Robert Lewis (December 2020)

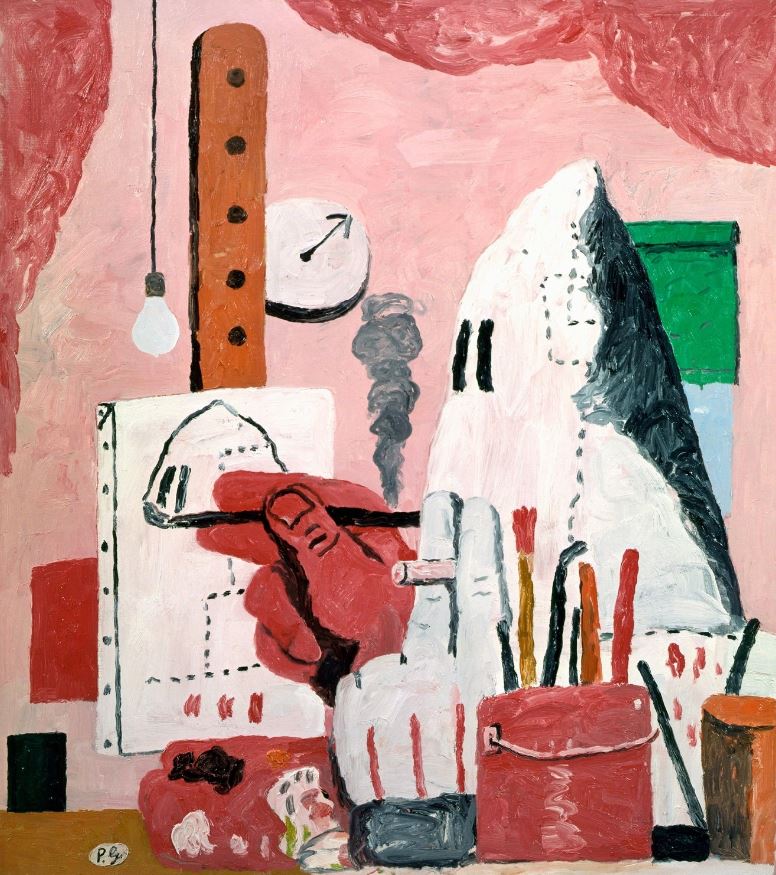

The Studio, Philip Guston, 1969

To think is to confine yourself to a single thought that one day stands still like a star in the world’s sky.

—Martin Heidegger

What is time? The question of all questions for which we have never had so much time. One could argue that since St. Augustine’s brilliant 4th century treatise, The Confessions, Book 11, Chapters 14-29—which remains unsurpassed—we haven’t gotten any closer to understanding what is meant by time passing, or to be in time.

Following the publication of The Confessions, only the hardiest of metaphysicians has done battle with the concept—and with good reason: our timepieces tell us next to nothing about it, the subject is invisible, and the more we interrogate it the more it seems to resist our best efforts. Like the wind, we are always in its midst but can’t get a grip on it and yet everything that exists is enfolded within it. Hobbes describes time as “perpetually perishing parts of succession:” we admire the locution and then admit to frustration. Or do we? I suspect for most of us, the time question isn’t a priority because it’s like the sky, always in surplus, “here, there and everywhere.”

Nonetheless, since we are mortal, time will one day reveal itself as something that is not to be taken for granted. We know that the past is fixed for all time, and the future is unknowable, and the future must pass through the present to get to the past, but what about the present, which is always here and now, and how are we implicated in it? We are often accused of spending too much time thinking about the future or living in the past, as if it were possible not to be in the present. And yet our experience tells us we’re always in present time, even when recalling the past or anticipating the future, because our bodies are anchored in the present, and, pace Merleau-Ponty, there’s no escaping the body.

But that doesn’t tell us much about the present. Consider the sentence: Martin lives in Montreal. When we speak it out loud, as soon as we begin to verbalize the ‘tin’ (2nd syllable in Martin), the first syllable, ‘Mar,’ is already in the past, just as the ‘lives in Montreal’ doesn’t exist yet because it hasn’t been said. When we speak the ‘a’ in Martin, the ‘m’ is in the past, and the same again for the first part of the letter ‘m’ when the latter part is spoken. In other words, the present is continuously disappearing into the past and seems to have no duration. What is the status of anything that has no duration? Or, since the present is so brief, of quantum duration, what can we say about entities (rocks, plants, porcupines) that exist only in the present, that have no conception of a future or past?

We say an animal exists because “we know” it exists over time, but the animal—from the point of view of the present where it always is, where its continuously unfolding present is always disappearing or being replaced by a succeeding present—doesn’t experience meaningful existence as we know it because it doesn’t have access to the traces of itself it leaves in the past. From its sole (disad)vantage point, which is the pure, unmediated present, the animal, at every instant of its existence, is disappearing or losing itself, which is why it doesn’t have a self—not unlike the time-challenged protagonist (Leonard Shelby) in Christopher Nolan’s film Memento.

Does this mean that the present doesn’t exist or, if it does, it is so short-lived as to have no practical significance? If we were to represent the present numerically, we would, by default, assign it the number zero, whose zero value is redeemed by the important place it occupies between the future and past, (between positive and negative integers). But we do not buy into the proposition that the present doesn’t or hardly exists or has the value of zero because we all know and feel that we exist in the present, even though we have just logically demonstrated that as soon as the present arrives it immediately becomes part of the past. Therefore, since we don’t accept what reason tells us about the present, (that it almost doesn’t exist) it must mean that reason alone cannot account for what we mean by the present, and beyond that, what makes it meaningful.

We all share in the certainty that we are in the world and are constantly providing ourselves future projects: tomorrow I plan to shovel snow, on Monday I have to go to work. Even the person who claims he’s doing absolutely nothing is still projecting, however minimally, into some nominal future, if only to feed himself and perform his bodily functions.

When we ask ourselves what best describes the time we’re in when we find ourselves performing or answering to our future projects, we always describe the activity in terms of a “now” time. What is he doing (now)? He’s shopping for groceries (now). Whatever it is we’re doing in what we feel is the present is in fact taking place in the “now,” which, unlike the present, endures until what we’re doing is completed. True, in any given “now,” as delimited by a particular activity, there are an infinite number of infinitesimal presents slipping into the past, but this only highlights the distinction that “the present” is merely a scientific indicator while “the now” is an existential one, the former referring to an infinite succession of nano-presents, the latter to human endeavor. If I am shopping at a supermarket, what I am doing “now,” for as long as it takes, is shopping. True, the apples I have placed in the cart is an activity that already belongs to the past, and the oranges I am planning to purchase haven’t yet been bagged, but all of these gestures, united in sequence and purpose, fall within the purview of “now” time. Only when I have selected the food items on the list, paid for them, driven home and shelved them, and then begun another activity (there is always another activity) can the act of shopping be said to be done and belong wholly to the past.

In other words, it isn’t present-time but now-time that provides for the sum of human activity that underlies the basic notion that we are intentionally in the world, constantly projecting ourselves into the future. Time is not a grid or background where our existence unfolds: it is our uniquely human manner of being in the world. Time passing is the defining gesture of ourselves in the world which includes other selves and all that which constitutes the world.

When we are without a project, as in sleep, which takes place in pure present time, we do not meaningfully exist because we have no access to any past or future. Like animals, we exist in a present which has no duration—until we wake.

Humans are uniquely empowered to survive the pure, unmediated present disappearing into the past, which is what happens at every instant of existence, because we are endowed with the means to access the past, as well as project into the future. This ability to access the past is an essential attribute of now-time, without which it would be impossible to meaningfully exist in time.

__________________________________

Robert Lewis was born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. He has been publislhed in The Spectator. He is also a guitarist who composes in the Alt-Classical style. You can listen here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast