Memories and Rosenbluth

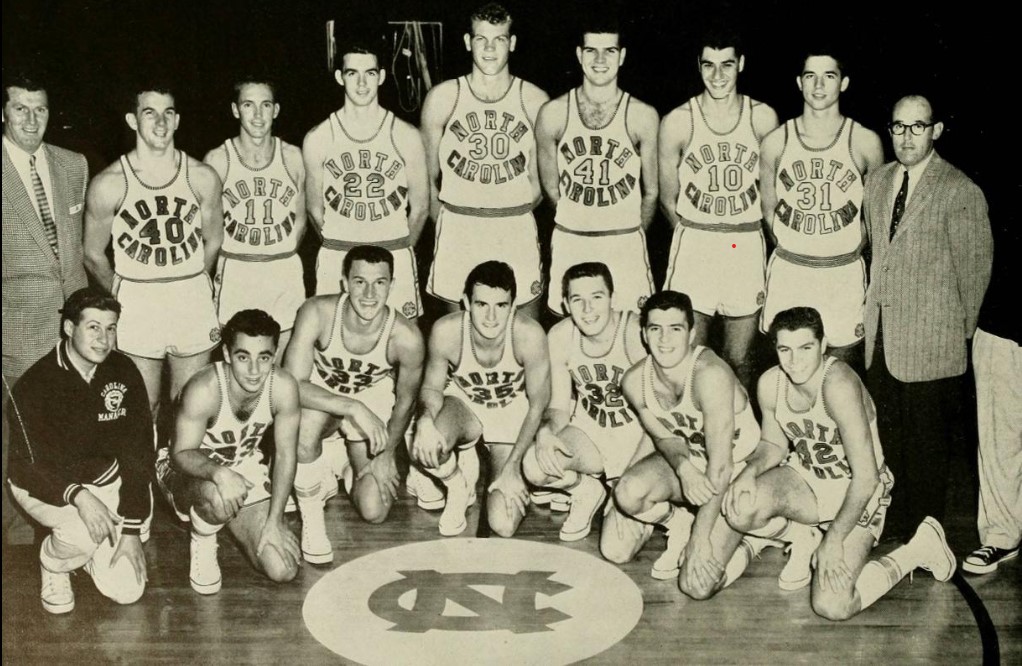

The 1956-57 national champion UNC Tar Heels

I mourn the death (18 June 2022) of Lennie Rosenbluth, the greatest basketball player I ever saw with my own eyes either in the flesh or on TV. I am sure many fans, foreigners to the University of North Carolina, would say “Lennie Who?” who would not say “Michael Who?” were I to mention Michael Jordan, a much more famous Tarheel given his long career in the NBA (National Basketball Association). A bit of an introduction is in order.

Given his play during the 1956-57 season Lennie Rosenbluth was not only All-American (for the third time) but beat out the great Wilt Chamberlain as the Helms Foundation Hall of Fame Collegiate Player of the Year. Lennie “beat out” Wilt in another way as well: North Carolina beat Kansas in triple-overtime to win the NCAA Basketball Tournament Championship, finishing undefeated for the season, 32-0. I am comfortable saying that UNC’s team that season was the greatest college team in history.

When Carolina beat Kansas, Rosenbluth, an aggressive defender as well as a scorer (who still holds all major records at Chapel Hill) fouled out late in regulation after his 20 points, so the rest of the team had to pull off the triple overtime victory (pretty worn out after the triple timer against Michigan State the night before). Their names should not disappear. With Rosenbluth (6’5”) at small forward was Pete Brennan (6’6”) at power forward, Joe Quigg (6’9”) at center, and Bob Cunningham (6’4”) at an unorthodox third forward, primarily a defensive insurance—in the unorthodox line-up of Frank McGuire (first of UNC’s genius coaches before Dean Smith and Roy Williams)—which left space for but one guard, Tommy Kearns (5’11”), both point guard and shooting guard combined in one compact body. Kearns, by the way, like Rosenbluth was All-American, even if “only” second team. I should mention also the 6th man Bob Young (6’6”) who replaced Rosenbluth so admirably in the overtimes. Let no one tell me about the great UCLA teams of John Wooden; I’m talking about one team for one season.

One other notable thing about this line-up: while UNC at Chapel Hill has long been not only a state university but like its traditional rival Duke a national university as well with a student body from god-knows-where, still the absence of southern drawls on the court was loud, as all five starters and the sixth man were from the New York City metropolitan area. . . youngsters who might have chosen St. John’s University followed Coach McGuire to Chapel Hill instead.

Having mentioned Duke as a UNC rival above I feel compelled to interrupt with this digression. The athletic—and scholastic—rivalries were intense within the “Research Triangle”: Raleigh (North Carolina State), Durham (Duke), Chapel Hill (UNC), with no team 25 miles from another, which means that a visiting team will have healthy numbers of its student-fans in attendance. Duke and Carolina are 9.8 miles apart. (When Wake Forest was in its original location before moving to Winston Salem in 1956, rivalries were even more geographically intense: the town of “Wake Forest” is really a suburb of Raleigh.) When NC State (which should be named “North Carolina Tech” since it does what Georgia Tech and Virginia Tech do for their states) visits Duke, the State fans and team can expect Duke students to be chanting “If you can’t go to college, go to State.” The Duke students have a reputation, earned, for arrogance. But, no matter that Duke is supposed to be a genteel university, they have a reputation for nastiness as well. A few years ago Carolina coach Roy Williams gave Rosenbluth and Young, who often visited Chapel Hill during the season, tickets for a Carolina-Duke game to be played in Durham. According to Young, he and Lennie preferred to watch the game on TV in a local hotel. “I didn’t want to be spat upon,” said Young.

I was in Chapel Hill that magical year 56-57, and there was nothing like it! I realize this confession will lead some to think my judgment is prejudiced. As will the next memory: one of the Tarheels was a friend of mine, the back-up forward Roy Searcy (6’4”), one of three native Carolinians on the varsity. Perhaps I should admit that Roy was a fraternity brother—although I am almost embarrassed to confess I was once a frat boy. But after my enlistment in the army I was happy to join hometown friends in Zeta Psi, comfortable in a room in a house unlike a barracks-like dorm, dining in a civilized setting even with a waiter instead of standing in line in a giant cafeteria. It was a lovely way to go to college. Not that I was a typical “Zete” (pronounced Zate); I was far too intellectually inclined even then. I had a mild reputation of not always “acting like a Zete”—as when noticing the fraternity president carrying a copy of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man I said “Great book; I read it in the army!”; to which he answered, dismissing my enthusiasm, “It’s required.” (UNC was a real college, many requirements.) Not that I was a typical college intellectual either. Yes, I was a member of “The Philosophical Society of 1799,” which has a certain classy sound. But to be selected you had to be observed being outrageous in a public place, in a restaurant it was in my case, half-drunk and hilarious with an accidental audience in stitches. A fellow Zete named “Snake” observed me, forgave my bookishness, and I was “in.” The PS of 1799 was popularly known as “The Ugly Club.” Another frat brother was Tommy Kearns. Occasionally visiting the Zete house for entertaining confidences about The Atlantic Coast Conference—thanks to Roy and Tommy of course—was the fascinating Frank McGuire, no less. Memories, pleasant memories. Not that all my brothers do I recall pleasantly; but that’s for later on … But is it any wonder that the magical year of Tarheel glory remains so rich in memories for me? Things could have been topped only if Lennie had been a brother. (As he could not have been at that time.)

My most dramatic memory of that year took place in the Zete house as I watched with mates the TV broadcast of the UNC-Kansas championship game. In the third overtime Carolina took the lead, 54-53, with only a few seconds to go on two free-throws by Joe Quigg. Kansas could not respond as Quigg tipped the Kansas in-bound pass and Tommy Kearns ended up with the ball, and with less than five seconds left, instead of risking a steal he tossed the ball straight up toward the rafters, and when the ball landed the game was over. (“I guess I wanted to make sure Wilt didn’t touch the ball again,” he later said.) The Zete house exploded.

Here’s another memory, which however, has nothing to do with UNC’s great season—but remains a significant source of pride. Fraternities like to “rush” athletes, so Roy Searcy, who’d been a high school super star like Tommy Kearns, was a natural, although a country boy from a NC hick town. During that year Zete Psi had a special Fathers’ Day (not the official June celebration) to which dads were invited, and a couple dozen did indeed appear: physicians, lawyers, business executives, etc., all looking and dressed as one would expect. Except for Roy Searcy’s father. Everything about Mr. Searcy—dress, general demeanor, haircut, you-name-it—had dirt farmer written all over him. He obviously felt out of place, and must have felt more so as the other papas, many of them old Zetes themselves, ignored him. He stood alone, attended to by his son … and by yours truly as I stood by Roy, waiting for the appearance of my own father, who was a bit late arriving. No gentleman ever looked more “presentable” than my father. He did arrive, nodded at me, looked about, sizing things up, then walked straight up to Mr. Searcy, shook his hand and introduced himself … and spent the brunt of the afternoon in conversation with Roy’s pop about farms in general, the crops, the prospect for the market, and god-knows-what-else. Quite unexpectedly, given how things began, Mr. Searcy had a wonderful time in intense conversation with this auctioneer (whom he might even have heard on radio: “sold to Liggett and Myers”), a bright smile on his weathered face the whole time. And I felt proud of Howard McDaniel Hux, “Mack,” as I always did.

Recalling a few of the Old Zetes of that afternoon I think of the expression “like father like son.” I have pleasant memories of most of my frat brothers, especially those from my hometown, Roy and Tommy, and notably an intellectually inclined pal who took some Comp Lit courses with me, who although a gentile like all the Zetes was surprisingly a young friend of the Ukrainian-born Harry Golden, author of Only in America and editor of the Carolina Israelite—which I casually mention for a certain context. But, one Zete I disliked so intensely that I have obliterated his name beyond recollection, and I imagine he’s done the same to mine. I know he was not “Prichard,” but I will call him “Prick” nonetheless. And to assure the reader I have not gotten beyond reach of the theme with which this essay began: this will lead us back to Lennie Rosenbluth.

I can guess why Prick disliked me, as he obviously did. I had a “steady” two years younger than I for two years in high school, who, for no good reason that I can recall, I am ashamed to say, I ceased being steady with in my senior year. Now (or rather after) at Carolina she was Prick’s girlfriend—and, for her own sake, I hope not his wife to be. I do not recall her ever speaking directly to me at the Zete house; I only recall it being very awkward. Perhaps she told Prick about her history, perhaps he felt angry that I had been there first, perhaps whatever and whatnot, but in any case, he became ice cold to me and that never changed. A memory leaps unbidden to mind. At a special party (I forget the occasion) I asked my woman if she would mind removing a high-heel, which she did, into which I poured champagne and quaffed it and dried the shoe with my necktie. She thought it hilarious. I thought it comically gallant. Prick was practically ballistic with disgust, the most disgusting thing he’d ever seen. I hasten to add that this is not why I disliked him so intensely. Rather:

Rosenbluth was obviously Jewish, a handsome devil with dark hair and tanned, almost olive, skin. Prick was a fan, like “everyone” else in Chapel Hill. He had to “accept” Lennie, whose excellence was so extremely compelling, whose movements on the court were balletic; but he could not quite accept Lennie as Lennie. This little antisemite—and racist to boot—knew better than to use the most derisive terms. Proper Zeta Psi boys did not say “Kike,” and “Yid” was not available to Prick, who would never have heard of Yiddish. The only verbal derision available to him would be “The Chosen People” with a sneer or “Jew” pronounced not Joo but sneeringly Jee-yoo. “Nigger” was too vulgar for one of Prick’s “class” as was “Coon,” and it is difficult to get a real sneer onto “Negro” whether pronounced Nee-grow or Nig-ruh, as it usually was in those days. So Prick was delighted and proud to have come up with (whether he invented it or not) “Roid”—obviously short for Negroid—which he used constantly, Roid this and Roid that, meaning of course Nigger this and Nigger that.

I seldom heard Prick call Lennie Rosenbluth by first or family name; rather he consistently enjoyed his invention—although never in Roy’s or Tommy’s hearing—“The Golden Roid”! I think I have named Prick well.

Another notable thing about those New York Tarheels was their surprising lack of success as professional players. Like 6th man Bob Young in 1957, Bob Cunningham was not drafted by the NBA after finishing his career at Carolina in 1957-58, which was the senior year of Joe Quigg, Pete Brennan, and Tommy Kearns as well. Quigg’s was a special case. His senior year was lost to a broken leg; but he was so good that the New York Knicks gambled by drafting him. The gamble was no good: the leg was in effect gone. So pre-med Joe returned to school and became a dentist. Brennan was ACC (Atlantic Coast Conference) Player of the Year as a senior and second team All-American. No surprise that he was drafted by the Knicks, for whom he played 16 games for Coach Andrew Levane (who compiled a career .384 winning average!)—and that was Pete’s pro career. This is impossible to understand, making you wonder what the hell was going on. I spent three years observing Pete in college: just what you want in the fore-court, scoring, rebounding, both in double figures, and throwing his weight around on defense. Something is radically wrong here! This competes with the fate of Tommy Kearns, who was drafted by the Syracuse Nationals, for whom he played one game, with one shot for two points. . . and then was dropped for the much taller point guard Hal Greer. One thing for certain, losing coach Paul Seymour was no genius: “who wants two first-class point guards?” he must have thought. Playing coaches, distracted by their dual roles, don’t know what the hell they are doing.

I could write an essay itself, maybe a book, on extraordinarily foolish decisions made by coaches and managers, especially in baseball, but a football decision strikes me as in the same league as the Brennan and Kearns stories. Seven games into the 2011 season Tim Tebow, “God’s Quarterback,” took over the Denver Broncos from Kyle Orton and led them into the playoffs, before losing to the New England Patriots and the great Tom Brady. Despite his sensational play he was criticized by those “in the know” for his unorthodox style (but not by my spouse who became a football fan overnight when she saw one Tebow game). Those in the know knew that if you want a winner you need a conventional pro-set quarterback safe in the protective pocket and preferably a right-hander, whereas southpaw Tebow was as likely to run as throw. When the Broncos after season’s end picked up the great Peyton Manning Tebow was traded to the New York Jets in 2012. In spite of starter Mark Sanchez’s horrible year Tebow was used or misused as a seldom employed back-up. After all, everyone in the know knew that the defense will adjust to the freewheeling unpredictable-ness of a Tebow faster than to the predictable pro-set quarterback seen every day. In other words it is easier to defend against what you don’t know is going to happen than against what you expect to occur. The rumbling sound you hear is logicians turning over in their graves. In 2013 the Patriots picked up Tebow as a back-up to Brady in the preseason. Tebow passed for only 26 percent receptions but a remarkable 40 percent of his completions were for touchdowns, and on 10 carries he gained 61 yards. Then he was released: evidently the last thing you want is a runner who gains 6 yards per run. Since Coach Bill Belichick is a recognized genius this must make sense. NFL wisdom is very strange. (Perhaps Coach Bill isn’t so smart, as his competition with the man who made him “a genius,” Tom Brady, drove Brady away. The great Casey Stengel famously said, “I couldn’t have done it without my players,” but Belichick is no humorist.)

Ironically, the merely so-so professional career of the greatest I ever saw, Lennie Rosenbluth, was the least surprising. What follows is not a digression.

Basketball has changed much more than the others of the three major American sports. In spite of the designated hitter rule Baseball is still the same game it has been since the mid-1890s, a battle between pitcher and batter, size of players mostly irrelevant. Whether a coach stresses the running game or the passing game, Football requires a quarterback with an arm, runners, receivers, and defensive backs with speed, linebackers large but swift, linemen offensive and defensive very large. Of course large is relative: I was a 190 pound interior lineman in high school, when college tackles were 225 or so. Now in the pro game interior linemen approach and pass 300, But it’s still essentially the same game. But not Basketball …

College ball was more deliberate, mental and tactical. Note for instance McGuire’s three forward offense, which made in effect an extra defender: Bob Cunningham never reached double figures on offense, saving his energy to annoy the opposing offense to pieces. Dean Smith’s floor formations were inspired. Amateur theologian Smith was always thinking. The players were students. The players were smart. Of course they were also tall, the point guard the possible exception. Not as tall as they would become: there were few 7-footers when Joe Quigg was a giant at 6’9”. But by the late 1950s the professional game was changing in essentially two significant ways. (1) Rarely would there be 50-60 point games and soon 100 points or more would be the expectation. Not because players learned to shoot better or defenders forgot how to do the job, but because the NBA responded to the perception that fans demanded more scoring. (Note for instance the American prejudice against the low scores of soccer). So the game became a matter of bodies running, shooting, banging, running back the other direction, as boring a game as an intelligent person can imagine. (2) Players became much larger. Not just taller, although guards often were the size of small forwards, but bigger. Forwards and centers began to look like linebackers, and some like interior linemen, until eventually … (Well, think a bit later of monsters like Shaquille O’Neal, 325 pounds!). Play in the fore-court, especially under the basket, became in effect a contact sport, which referees allowed unless just too blatant, with six fouls instead of the collegiate five, and far fewer roughnecks fouling out nonetheless given referee liberalism.

This was no game for an artist like Lennie Rosenbluth, tall enough for a small forward at 6’5”—yes—but rail thin for a man of his height! Nonetheless he lasted for two years with the Philadelphia Warriors. And that was it and he retired. How the Warriors could have kept him at a contact position (!) is beyond me. NBA logic as strange as NFL’s. I watched him for two years at Carolina and found his ball-handling amazing. He had the agility and judgment of a point guard had he been needed, as he was not of course with Tommy Kearns there; but with his accuracy (a reliable 27 per game as a Tarheel) he was made for a professional shooting guard, and wasted in the contact fore-court game.

So Lennie Rosenbluth, not your common phiz-ed student but a History major, returned to North Carolina and then Florida as a high-school History teacher and coach. After decades in Florida, he moved back to Chapel Hill when his wife was diagnosed with cancer in order that she have the care of the UNC Medical Center … and there he remained until he died at 89, a legend, long enshrined in the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame as well as the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in Israel.

I should mention that all six of the New York Tarheels defied the often-just caricature of pro athletes as educational retards. Cunningham and Brennan were successful business executives. As already noted, Rosenbluth a historian, Quigg a dentist. Kearns became a broker and investment banker. And 6th man Bob Young followed his English major into publishing, The New Yorker and The New York Times. There was a time when “student-athlete” was not a joke: when college athletes were college students.

Fans of the last 40 years or so will remember the likes of Julius Erving, Michael Jordan, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, Shaquille O’Neal, Stephen Curry, Kobe Bryant, LeBron James, to name but a few super-stars. But they will not have seen Leonard Robert Rosenbluth. I’m one of the blessed.

Samuel Hux is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at York College of the City University of New York. He has published in Dissent, The New Republic, Saturday Review, Moment, Antioch Review, Commonweal, New Oxford Review, Midstream, Commentary, Modern Age, Worldview, The New Criterion and many others. His new book is Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Kenneth Francis)

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast