by Pedro Blas González (February 2020)

.jpg)

Melancholy, Edvard Munch, 1894

Those surges of love that flow into our chests and take our breath away—those illuminations, those ecstasies, inexplicable if we consider our biological nature, our status as simple primates—are extremely clear signs. —Houellebecq

Hedonism and Unhappiness

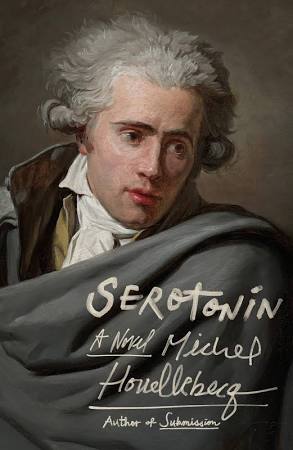

It is always a challenge to categorize a Michel Houellebecq novel. Serotonin: A Novel, published in November 2019, is no exception.

For starters, one can only imagine the plot of a novel that has the name of a monoamine neurotransmitter as part of its title.

Because Houellebecq is a maverick in a time of censorship, readers of his work must come armed with a fresh sense of satire. I say fresh, because the old form of satire, which relies on heuristic wisdom for its effect, no longer enjoys the power of persuasion in postmodernity.

Unlike Swift’s sanguine satire, which attempted to change the world—as that hollow, politically charged term is overused today—Houellebecq’s satire is gritty, employing street fighter wit and ready to pounce on the hypocrisy and affectation of postmodern leftism. His hardnosed, Voltaire-like approach to human reality spars with politically correct pedantry.

Unlike Swift’s sanguine satire, which attempted to change the world—as that hollow, politically charged term is overused today—Houellebecq’s satire is gritty, employing street fighter wit and ready to pounce on the hypocrisy and affectation of postmodern leftism. His hardnosed, Voltaire-like approach to human reality spars with politically correct pedantry.

In order for satire to be effective, readers must do their part to understand the real-world faux values that imaginative satiric writers confront. False values say much about the temporary, live and let live values of not only hedonists, but people who are generally jaded by life.

For satire to be highly effective, readers must possess the same wit and perspicuity that good writers of satire bring to their work—to the table, as it were. This requires independent thinking and courage to see through the steady flow of moral and existential dilemmas that daily life throws at us.

Non-fiction essay writers who discuss the debased moral, social and spiritual conditions that inform the life of a character like Labrouste—the protagonist of Michael Houellebecq’s last novel Serotonin: A Novel—always run into accusations of puritanism and moralizing. This is because in essay form, writers explore the underlying values and choices in the miserable life of people like Labrouste.

Read more in New English Review:

• Old Books and Contemporary Challenges

• Continuing Corruption in Equatorial Guinea

• China’s Growing Biotech Threat

Houellebecq’s fictional treatment of the aberrant values that Labrouste embraces also incite indignation in postmodern literati chic circles. Why the hypocrisy?

One reason for this is that literati chic refuses to admit that people like Labrouste lead destructive and meaningless lives, reinforced by aberrant real-world conditions that postmodernity has ushered in. This is the same postmodernism they applaud for creating an unprecedented degree of moral liberation. This is the kind of virulent hypocrisy that Houellebecq slashes like a man possessed.

By denouncing debauchery and moral deviancy in works of fiction, postmodern hedonists create the affected illusion of embracing constructive values that make postmodern man a better citizen of the world.

The protagonist of Serotonin, Florent-Claude Labrouste, a forty-six-year-old agronomist hates his first name. This is how the narrator introduces the narrative that follows the trajectory of this unhappy man.

Labrouste, like many postmodern hedonists, may be an unhappy man but this does not mean that he doesn’t gravitate from pleasure to pleasure. This is the main point that Houellebecq makes about the corrosive nature of hedonism’s gutted house of values.

As unhappy as Labrouste will turn out to be, readers are first introduced to a man who is not so much unhappy as he is a poster child for postmodern moral decrepitude. This is why several times in the novel the author reminds readers that our decisions are never without consequences. In Labrouste’s case, his moral failings ultimately deliver him to a life of self-destruction: “I was now in my own hell; which I had built to my own taste.”

Labrouste lives his life without a moral compass. He does not need one, the narrator suggests, for the pursuit of pleasure has a logic of its own. He is a postmodern hedonist, a hyper-liberated man who can only make sense of human reality by killing time. This is because in the absence of long-range ambition, Labrouste’s aspirations—it one can even identify these—are dictated by temporary and mundane gains. In Labrouste’s world, life is satiated by the here-and-now. And, what happens when one runs out of options?

Boredom and tedium choke the protagonist of Serotonin. This is one reason why he moves around so often. He cannot remain in one location for long. Labrouste is much like a millennial, stunted moral development and all, minus the pathological need to take selfies.

Houellebecq spends much effort describing high-end restaurants, sexy alcoholic beverages and touristic pleasure traps. This is indicative of the form of hedonism that Labrouste embraces and that fuel his moral vacuity. It is also indicative of a restless postmodern pathology that makes the protagonist believe that the grass is always greener on the other side.

In addition to being a satiric work, Serotonin: A Novel is also Houellebecq’s version of a horror story. This adds flair to the author’s critique of hollow postmodern values.

Serotonin is Frankenstein redux. The monster is a pleasure-seeking addict and self-consumed postmodern man. He is the omega of postmodern life, Houellebecq suggests. Labrouste is merely finishing what other hedonists and relativists before him started.

Labrouste is also the proto first-man of the future. This is part of the horror of Serotonin. The creator of the monster is not a mad scientist reminiscent of Victor Frankenstein, yet postmodern values create monsters nonetheless. How many people like Labrouste roam aimlessly and hopelessly through the postmodern world?

Houellebecq’s fiction is often not easy to stomach. His plots involve grotesque situations and topics that the vast majority of his readers would probably never embrace or tolerate in real life. This is not the point, however. Instead, Houellebecq simply stirs up the Pandora’s Box that self-serving relativists before him yanked open.

Labrouste’s existence is isolated from other people. What makes his life a cocoon existence is not physical proximity to others, rather his frigid and detached values. While he seeks love, he instead finds sex. The latter is an elixir to loneliness that is much easier to come by. Instead of finding lasting friendship, Labrouste encounters other people with whom he can compare his meaningless existence. This is a postmodern form of competing with the Joneses.

Serotonin begins by describing the life of fashionable European vacation spots. This is a favorite theme of Houellebecq’s. Tourists meander from location to touristic location, not so much for fun but, as Houellebecq suggests, to kill time. They immerse themselves with abandonment “with exaggerated attention in the study of a menu, albeit a rather short one.”

Houellebecq is adept at describing the clash of libertinism in its theoretical call for liberation and the impact of its consequences on real-world values. The author is interested in addressing the question of what happens after false values have run their course. Houellebecq’s writing displays mastery over libertinism in Europe, and how these values have come to dominate the psyche of Western man.

One of the answers that Houellebecq suggests brings us to the word serotonin in the title of the novel. Because people no longer have the necessary values to sustain them through what many find to be an empty and often arduous life, Houellebecq suggests that postmodern human existence can only be tolerated by being medicated.

Serotonin weaves through topics that generally do not make easy reading. The themes of the novel are tough to navigate, because for people who are alien to many of the topics that the author explores, life does not mean doing battle with unhappiness.

A Surprising Redemption

We would never return to the tribal stage—though some unintelligent sociologists claim to be able to distinguish new tribes in ‘reconstructed families’, that was possible—but for my part I had never seen reconstructed families, deconstructed yes; in fact those were the only ones I’d ever seen at close quarters. Apart of course from the many cases in which the deconstructing process had already begun at the couple stage, before the production of children.—Houellebecq

Serotonin reaches a crescendo and denouement that cannot be identified solely with the author’s plot mechanism. This is the case because Houellebecq’s novels are works of ideas. His plots follow the trajectory of ideas and values, and play out their worth, always demonstrating how bad ideas lead to gutted real-world suffering.

Loveless. Having squandered several opportunities to cultivate a family—a late-life realization that Labrouste laments—the protagonist finds himself ultimately responsible for the failed life he has created for himself.

Read more in New English Review:

• Libraries That Don’t Repect Books

• Hyperbole and Anti-Woke Lyrics

• The Nihilists’ Masquerade

At the end of the novel, the author offers the reader a devastating critique of the “new” reconstructed family. Houellebecq counters this anthropological dysfunction by saying that the reconstructed family is actually a case of deconstruction: “This business of reconstructed families was, in my eyes, nothing but revolting hot air—although it wasn’t a piece of pure propaganda, optimistic and postmodern, unworldly and dedicated to the ABC+ and the ABC++ economic groups, already inaudible beyond the Porte de Charenton.” Thus, goes the truism that for good listeners, few words are needed. This is also true of alert readers.

Houellebecq ends Serotonin in a manner that exposes hedonism’s vacuous pleasurable slumber. He achieves this by invoking purpose and meaning in life—two fundamental components of existence that ward off the easy-street temptation of becoming a throw away—like Labrouste’s life.

Signs

The question of what constitutes a sign from God is what fuels the trajectory of Serotonin. Though, this is only made manifest at the end of the work. The conclusion of the novel is like the lifting of a theater curtain; from behind are revealed not greater horrors that Labrouste has embraced, but redemption for the protagonist, for Labrouste realizes that “God takes care of us; he thinks of us every minute, and he gives us instructions that are sometimes very precise.”

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

________________________

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link