Mozart and Mohammedanism

by Jeff Lipkes (September 2018)

.jpg)

Odalisques in a Harem, Artist Unknown, approx 1880

In Mozart’s tragically short lifetime, Die Entführing aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) was his most popular opera. It premiered in Vienna on July 16, 1782, and a week later Mozart wrote his father, “I must say that people are absolutely infatuated with this opera.” By the time of the composer’s death in 1791, there had been forty productions.

The opera tells the story of the attempted rescue by Belmonte, a Spanish aristocrat, of his fiancée Constanze, her English maid Blonde, and Blonde’s boyfriend Pedrillo. The three have been captured by Muslim pirates and sold as slaves to the Pasha Selim. The Pasha has fallen in love with Constanze, and his coarse major domo, Osmin, is infatuated with Blonde. The women remain loyal to their lovers, and resist the importunities of the two Muslims, Blonde scolding the overseer by telling him that as a liberated Englishwomen she expects to be wooed with civility and deference.

In the real world, of course, there would have been no “courtship” of the two captive women. The ruler and his servant would have had their way with their Christian slaves. In the real world, though, Osmin, in charge of the Pasha’s country house, would likely have been a eunuch, and would not be able to sing his deep baritone arias.

It’s what Mozart did to the libretto that’s of particular interest. Librettos were frequently recycled and the composer’s partner Gottlieb Stephanie simply appropriated an earlier text, Belmont und Konstanze, by Christoph Bretzner. In the original version, when the four Europeans are captured as they attempt to escape to Belmonte’s ship and are hauled before the Pasha, Selim suddenly recognizes Belmonte as his long-lost son. They joyfully embrace.

It’s what Mozart did to the libretto that’s of particular interest. Librettos were frequently recycled and the composer’s partner Gottlieb Stephanie simply appropriated an earlier text, Belmont und Konstanze, by Christoph Bretzner. In the original version, when the four Europeans are captured as they attempt to escape to Belmonte’s ship and are hauled before the Pasha, Selim suddenly recognizes Belmonte as his long-lost son. They joyfully embrace.

Mozart was not happy with this trite denouement. The Pasha, the composer decided, rather than being Belmonte’s father, should instead have been the victim of the Spaniard’s wicked father, Lostados, the Commandant of Oran, who badly mistreated him. But Selim decides to repay evil with good, and liberates the four captives on the condition that they inform Lostados.

“I despised your father far too much ever to follow in his footsteps,” he tells Belmonte. “Take your freedom, take Constanze, tell your father that you were in my power, that I released you so that you might tell him that it is a far greater pleasure to repay injustices suffered by good deeds than to compensate evil by more evil.” When Osmin protests the loss of Blonde, the Pasha tells him, “Old fellow—calm yourself. Those whom one cannot win over by kindness one has to release.”

“Never will I forget your benevolence,” Belmonte assures Selim, “For ever shall I sing your praises. In every place, at every time, I shall proclaim you great and noble.”

***

Ninety-nine years before the opera’s premiere, almost to the day, the troops of the Caliph of Islam commenced the siege of Vienna. Residents of the capital of the Hapsburg Empire, defended by only 15,000 soldiers, knew what was in store if they surrendered to the 140,000-man Ottoman Army. Perchtoldsdorf, ten miles south of Vienna, had handed over the keys of the city to the Turks after the commander, the Grand Vizier, Kara Mustapha Pasha, had promised that the lives and property of the residents would be respected. Instead, the town was ravaged, the civilians were slaughtered en masse, and the survivors sold into slavery.

The Ottoman campaign had been inspired by appeasement. Wanting to concentrate all his forces along the Rhine against Louis XIV, Emperor Leopold I had twice offered slices of Hungary to the Sultan. This only persuaded the Caliph that his rival was weak, and now would be an excellent time to attack the Holy Roman Empire.

But the Sultan prematurely declared war in August 1682. The campaign only got underway the following spring, so the Hapsburgs had time to make preparations and conclude alliances. The Ottomans made a second mistake. Camped outside Vienna in the summer of 1683, Kara Mustapha hoped to starve the city into submission so that he would have a greater share of the spoils.

King John III Sobieski after the Battle of Vienna, Jan Matejko, 1882

The delay was fatal. On September 12, the heavy cavalry of the Polish king, Jan Sobieski, thundered down Mount Kahlenberg into the Ottoman camp, while Imperial forces under Leopold and Charles of Lorraine attacked from the north and northwest. The Turkish besiegers were routed. Before he began his precipitous retreat, Kara Mustapha ordered the execution of nearly 30,000 Christian captives.

***

What had transformed the Cruel Turk into the Noble Turk less than a century later?

First, the Ottomans were no longer a threat to Europe. By 1687, most of Serbia, Hungary, and Transylvania were back in European hands. Ottoman losses in Southeastern Europe were officially recognized, after further fighting, by the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, and additional territory was ceded in the Treaty of Passarowitz nineteen years later. The Russians, meanwhile, were moving steadily down to the Black Sea and across the Dneiper River. For both European powers, there was a step backward for every two steps forward, but it seemed only a matter of time before the Turks would be driven out of Europe, as the Arabs and Berbers had been forced to abandon Spain.

There were other reasons for the new attitude. At the beginning of the 18th century, the pleasure-loving Ottoman court discovered Paris. Following the reports of envoys sent for the first time to France and Austria, a parade of architects and artists brought the Rococo to Constantinople. The tulip was re-imported from the Netherlands, and became a Turkish obsession. Delighted tourists and ambassadors reported on the extravagant son et lumières, tulip festivals, the coffee houses, bazaars, and fairy-tale palaces, the cultured and charming Sultan, Ahmet III, and the famous Seraglio, entered for the first time by Lady Mary Montagu-Wortley, wife of the British ambassador.

European intellectuals during the Enlightenment were also attracted to what they saw as the religious tolerance of the Empire. As long as Muslim overlordship was acknowledged and the jizya paid, Orthodox, Catholics, Protestants, and Jews were free to practice their religion, and were taxed and governed by leaders of their respective millets. Intellectuals also admired Muslim abstinence from alcohol and the fact that justice was dispensed, they believed, quickly and cheaply.

There was a third reason for the shift in sentiments. After a long interval of peace in the middle of the century, the Russians won a crushing victory in 1774. The Treaty of Kuchuk Kainardji awarded them the Black Sea coast, control of the future Romania, the right to trade throughout the Empire, and to become, in effect, the guardian of Christians under Ottoman rule.

The Austrians began to be more worried about the Russians than the Turks. Soon the British, ensconced in India, would be as well.

But a much older Western mental habit was also responsible for Mozart’s rosy perspective on Islam: lacerating self-criticism, something no other civilization has indulged in. The form it often took was to attribute all virtue to the enemy and all vices to one’s own people. The habit has a long history. In 5th century B.C. Athens, audiences applauded Euripides’ prize-winning plays Hecuba and Trojan Woman. Both dramatize the cruelty of the Greeks to defenseless women and children in Troy following the capture of the city.

The Romans eventually mastered the art of self-flagellation. The best known examples are from Tacitus’s Agricola, written at the end of the 1st century A.D., in which he puts into the mouth of a British tribal leader the famous condemnation of the Romans, “the robbers of the earth”: “They give the false name ‘empire’ to plunder and slaughter; where they make a desert, they call it peace.” In fact, Britain under Roman rule enjoyed nearly four centuries of peace and a level of prosperity that would not be surpassed until the 18th century. In Germania, Tacitus compared the nobility of the German barbarians to the depravity of the Romans: in Germany “no one laughs at vice; nor is it considered fashionable to seduce and be seduced… Good habits are more effective than good laws.”

The idea of the Noble Savage long predates Rousseau. The Catholic priest Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484-1566) defended human sacrifice among the Aztecs: their “religiosity surpassed all other nations, because the most religious nations are those that offer their own children in sacrifice for the good of their people.” Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) famously defended the “natural virtues” of cannibals in his essay “Des cannibales.” “I am not sorry that we should here take notice of the barbarous horror of so cruel an action, but that, seeing so clearly into their faults, we should be so blind to our own,” he wrote.

During the Enlightenment, the first epistolary novel, Persian Letters by Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755), used the device of a Persian aristocrat traveling in France to criticize Parisian manners and morals.

Montaigne didn’t quite let the cannibals off the hook, and Montesquieu introduced in a sub-plot a revolt among the women of Usbek’s harem back home in Persia. But just as the Noble Savage was a fiction—the real Chief Seattle, to take a recent example, murdered his rivals, owned slaves, and, like all aboriginal Americans, killed animals and destroyed vegetation with reckless abandon—so the enlightened pashas, amirs, and sultans also represented a romanticization of a much grimmer reality.

Constanze, Blonde, and Pedrillo had a lot of company. Ohio State historian Robert Davis has estimated that between 1530 and 1780 alone, some 1 to 1.25 million European Christians were captured and enslaved by Muslims. These were not just sailors and travelers. North African slavers repeatedly raided European territory. Even Iceland was not immune. During this period and earlier, as many as 3 million Slavs were captured in raids by Crimean Tatars, and tens of thousands of Christian children were seized in the Balkans in the annual “blood tax,” the devsirme, to serve in the Janissary corps and administration. Islamic slavers, Arabs in this case, also captured as many as 18 million Africans before the British intervened to end the trade in the 19th century. There are about 10,000 to 20,000 descendants of these slaves in Turkey today. The 400,000 African slaves shipped to North America have 39 million descendants.

The Mediterranean slave trade was sustained by the demand for workers in quarries, on estates, in the galleys of the corsairs, and, of course, in the seraglios of the Selims of the Middle East.

***

In addition to sentimentalizing what would come to be called “the Other,” Westerners were also intent on studying foreign cultures closely. In this respect, too, they were unique. The very first Greek historian, Herodotus (484-425 B.C.), included in his Histories an invaluable ethnographic survey of most of the known world.

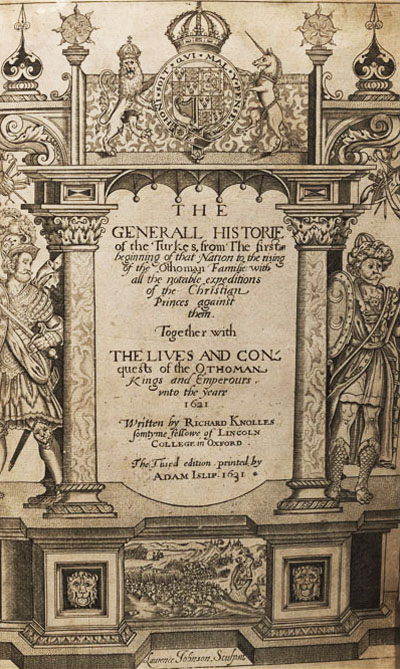

The first book to be printed in England, Dictes [sic] and Sayings of the Philosophers (1477), was an English translation of an Arabic book by Mubashir Ibn Fatik. By 1603, when Richard Knolles’ comprehensive The Generall Historie of the Turkes was published, 49 other books on the Ottomans had been printed in England, some of them by slaves who had escaped from Dar al-Islam.

The first book to be printed in England, Dictes [sic] and Sayings of the Philosophers (1477), was an English translation of an Arabic book by Mubashir Ibn Fatik. By 1603, when Richard Knolles’ comprehensive The Generall Historie of the Turkes was published, 49 other books on the Ottomans had been printed in England, some of them by slaves who had escaped from Dar al-Islam.

Meanwhile, back in the Turkish Empire, the printing press had not even been introduced. The first one appeared only in 1727, imported by a Hungarian convert, and by 1815 a mere 63 titles had been published. (Gutenberg’s Bible dates from 1454 and some 30,000 titles had been printed in Europe by 1500.) Nearly two hundred years before the first press appeared in the Caliphate, the Qur’an, in Arabic, was printed in Venice (1530).

Chairs in Arabic were established in Paris in 1538, Cambridge in 1632, and Oxford in 1636. Edward Gibbon went up to Oxford in 1752 intending to study Arabic because, he wrote, “Oriental learning has always been the pride of Oxford.”

***

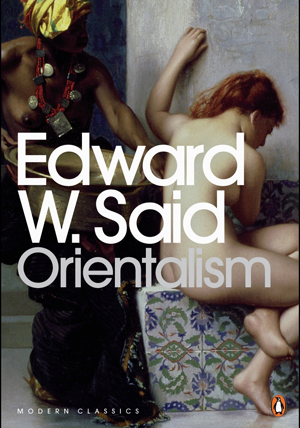

It’s worth recalling the centuries of scholarship by Western Arabists because, as anyone who follows intellectual fads and fashions knows, these have been sweepingly dismissed by Edward Said in a book still reverently cited ad nauseum, Orientalism.

The book remains one of the core texts of the religion of multiculturalism. The term “orientalism” is bandied about with nearly the frequency, and all of the care and discrimination, of leftist canards like “racist,” “sexist,” “fascist,” or “wingnut.” It’s worth spending a moment on this term of abuse.

The book remains one of the core texts of the religion of multiculturalism. The term “orientalism” is bandied about with nearly the frequency, and all of the care and discrimination, of leftist canards like “racist,” “sexist,” “fascist,” or “wingnut.” It’s worth spending a moment on this term of abuse.

Just as he had fabricated his Palestinian background until outed by Justus Weiner, so in his landmark book, the professor of comparative literature at Columbia borrowed his thesis from a more sophisticated and perceptive book on India, La Renaissance orientale by Raymond Schwab, substituting Islamic studies for Indic studies. He then reiterated accusations already hurled by Islamacists against heathens daring to write about the Muslim world. To these he added a large dollop of post-structuralist jargon, and chose to treat alongside actual scholarship the works of novelists and painters who made no claim to be providing realistic accounts of the East.

A few points about “orientalism,” a term described more than twenty years ago by Bernard Lewis as “polluted beyond salvation.”

- There are no comparable objections from Chinese, Japanese, or Indian scholars to the work of their Western counterparts. They are not Muslims. Indians acknowledge the achievements of British philologists, historians, and archeologists in rescuing much of ancient Indian culture. Gandhi first encountered the Bhagavad Gita, his Bible, in an English translation in London. The great Buddhist emperor Ashoka, whose wheel adorns the flag of India, had been forgotten on the subcontinent until British archeologists began digging.

Many genuine “Orientalist” scholars in the Arab world, it should be said, appreciate the contributions of their American, British, and French colleagues.

- Knowledge serves power, according to Said, and one of the central ideas of Orientalism is that scholars were partners with Western imperialists, for whom they provided rationales. But unlike in India, there was no prolonged Western occupation of the Middle East; it was not a European colony. The Middle East was governed by the Ottoman Empire until 1920. The Mandate period, when British and French protectorates were established, lasted all of 28 years. British control of Egypt dates only from 1882, and British influence on Persia, which remained independent, gave way to Russian in the 1880s. Said, however, claims that “Britain and France dominated the Eastern Mediterranean from about the end of the seventeenth century on.” Any freshman who’s paid attention in a European History survey knows this is nonsense. Said later claims that the West “dominated” the East for 2,000 years, a more grotesque whopper—one reason British historian Robert Irwin has called Orientalism “a work of malignant charlatanry.” Irwin adds that it’s “a damning comment on the quality of intellectual life in Britain in recent decades that Said’s arguments could ever have been taken seriously.”

- Orientalism entirely ignores German contributions to “Orientalist” scholarship, which were more important than British or French. Why? Because Germany was not a colonial power in the Middle East. Said also ignores the contributions of Soviet scholars, atheists who did not disguise their contempt for Islam. Why? No enemies on the left, presumably, even though St. Petersburg and then Moscow ruled millions of Muslims.

- In dismissing the contributions of German scholars, the comp lit professor reveals an astonishing conception of what scholars actually do.

“What German Oriental scholarship did,” Said explains, “was to refine and elaborate techniques whose application was to texts, myths, ideas, and languages almost literally gathered from the Orient by imperial Britain and France.”

As Lewis points out, while it may be possible to “gather” a text, though the Germans certainly acquired these as well, how exactly does one “gather” a language? Are French and English scholars to be condemned for learning Arabic?

“Gather” is not an isolated slip. Elsewhere Said repeatedly uses words like “appropriate,” “wrench,” “ransack,” and “rape,” to describe the work of scholars. Just as Western readers were supposedly titillated by semi-pornographic representations of the Orient, so Said’s fans seem to enjoy the sexual innuendos he liberally interjects.

You can steal knowledge, apparently, just as the Greeks were supposed to have stolen African knowledge.

This is the kind of thinking that third-rate minds find irresistible.

Second-rate minds are more partial to a slightly more sophisticated epistemology. Knowledge is relative; everything reflects a power relationship. This is simply a recasting of a venerable Marxist dogma: art, literature, and philosophy represent a “superstructure” faithfully reflecting “the social relations of production.” As Said puts it, “Every European, was a racist, imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric.”

Unfortunately, as long as intellectual sophistication is equated with self-flagellation, historically illiterate reductivists like Said, with transparent political agendas, will be worshiped by those who are instructed by the New York Times, the New York Review of Books, and the New Yorker.

It’s no surprise, then, that everyone who writes about The Abduction from the Seraglio attacks the representation of Osmin, the gruff overseer, as a regrettable stereotype. Osmin is a buffoon as well as a bully: though a devout Muslim, he’s partial to wine, and Pedrillo, as part of the plot to free Constanze and Blonde, persuades him to drink some Cypriot wine to which he’s added a sedative.

And inevitably, to show they are au courant, critics of the opera reference “orientalism,” and applaud “the new appreciation of the East” gained by the Westerners.

And inevitably, to show they are au courant, critics of the opera reference “orientalism,” and applaud “the new appreciation of the East” gained by the Westerners.

The Magic Flute is a fairytale, with all the improbabilities of that genre. The three great operas Mozart wrote with Lorenzo da Ponte depend on disguises that are hardly less improbable. Donna Ana fails to recognize her would-be rapist, who conceals himself with a large hat. Donna Elvira doesn’t recognize Leporello when he puts on his master’s clothes. Count Almaviva fails to identify his wife when she dresses in her servant’s clothes. And Fiordiligi and Dorabella don’t recognize their fiancés when they wear false moustaches and exotic costumes.

But in representing the Pasha as a compassionate and enlightened European, Mozart exceeded these improbabilities. What’s remarkable about The Abduction is the composer’s “occidentalism.”

An earlier version of this article was published in American Thinker.

______________________________

Jeff Lipkes is the author Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, 1914 and Politics, Religion, and Classical Political Economy in Britain, the co-translator of Henri Pirenne’s Belgium in the First World War, and the editor of a selection of the letters of Sir Edward Grey, Dear Kathryn Courageous. As Josh Michaels, he has written a novel, Outlaws, and edited and introduced a selection of the aphorisms of Mignon McLaughlin, Aperçus. He is completing a volume on the books read by American antisemites who read books. Many of his non-scholarly articles are available at American Thinker. For more information, see jefflipkes.com

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast