On Rotting Hill

by Robert Gear (June 2022)

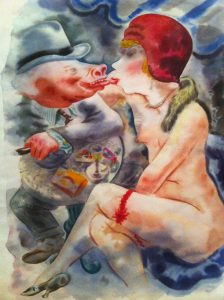

Circe, George Grosz, 1927

The farm-dwelling races, to which so many readers may belong, have been shoving their noses in the trough from the beginning, and will probably do so till the end; this is part of their feeding trajectory. But this story does not really have an end, just as no story really ends. Only at the end of time will entropy finally prevail. Then all stories will drain down through the hole at the bottom of the giant trough, leaving an unseen emptiness behind; at least for livestock and friends. And perhaps too the pulsing universe will start again, big-banging or whimpering its way from tragedy to farce (or the reverse).

It has been said that Malarky’s origins go way back before the time when time was measured. He was once a baby in a perambulator, and when the firing started his mother let go out of surprise and the conveyance jolted down, bounce, bounce, bounce, one hundred steps down. It traversed the intermediate landings, sped across the corniche and ran into the harbor below the town of Rotting Hill, with a splash.

A careful observer might have detected the young child’s pink arms waving joyously at the rhythm of the descent. Baby and carriage floated away across the harbor past the great ironclad battleships moored in readiness, their big guns pointing here and there, up and down. He floated out to sea, and the mother gave up hope of retrieving her little one.

Nothing more was heard of baby Malarky until a generation or so later. It is true, though, that several legends have sprung up about this obscure period of his life. If more come to light I will naturally make them available.

I think we can discount as false the story that he was found on the banks of the Delaware River and then suckled by a spotted-hyena bitch. Such stories usually turn out to be fictions; not at all reliable, even by the exacting standards of our own Ministry of MyTruth.

He rode back up to the town in the depths of winter and in most humble circumstances, sitting upright in a cart. The cart came out of the tunnel pulled by two donkeys through the snow-clad fields right up to the top of the magnificent staircase where we first made his acquaintance. In the sky above twin ravens circled waiting for messages which they could spread to outlying districts.

Malarky had grown into a fine pig of the Berkshire variety. Instead of pink baby arms, he waved his trotters and flung abuse at the toiling asses.

What was in the cart? A dozen or so chickens and a couple of squawking cockerels. They were both named Mo, and one had mostly white plumage and the other had mostly black.

The conveyance arrived, as I said, at the top of the magnificent staircase, and stopped beside a marble horse trough, the later habitat of lizard men as yet unseen.

The chickens fluttered out of the cart and pecked at the frozen ground. The donkeys just stood there, bewildered. Malarky, for his part, knew that his story had begun here and looked around tearfully for his mother, now long buried beneath the snow-covered landscape of forgotten virtue. He clenched the trotters at the end of his outstretched forelegs, and held them out horizontally as though trying to grip an invisible lectern. “Pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake, baker’s man,” he said, hoping in that way to gather an audience.

Then he spoke loudly into the surrounding space. His voice rippled out and down to the harbor where great warships lay scuttled.

Initially, only a few chickens and the two roosters named Mo paid any attention. Gradually the crowd grew, and soon included the now ubiquitous young Swedish actress with piggy tails and the ex-senator and Nobel laureate whose tendency was to dress up in a polar bear outfit purloined from the late Disney Business Model. The three mice, who had been blinded, made their way to the front of the gathering throng. The two donkeys paid no attention. They had heard and seen it all before, having read somewhere that there was no new thing under the sun. This wisdom they had discovered during the free time providentially allowed to them during their work assignments at the farm near Willingdon.

The ravens circled above, but could make neither beak nor feather of it. And so they could not spread the good news to the surrounding localities as they had been trained to do.

The site of this speech, which was also the site of his mother’s failure to hold onto the perambulator, was not in those days as it is now. Most of you know it now as the site of a sanctuary whose roof was held up by twelve great caryatids of Floyd, and whose roof long ago fell into disrepair and then into ruination.

In time, of course, Malarky’s speech became admired in those lands over The Big Water, since few could grasp its meaning. This pig spoke with the assistance of nothing but the notes that had been prepared for him to read. Animal looked to animal, chicken to pig, pig to chicken, the blinded mice at one another and at the ex-senator in the polar-bear suit. The young Swedish actress with piggy tails babbled about her stolen childhood. The two donkeys became more befuddled than even they imagined they could be, but by then they were not listening.

And so the words of Malarky, like those of Pericles, became legendary, remembered and much imitated wherever animals congregated. At the farm near Willingdon these words were even carved into the oaken lintel of the great entranceway above other words which suggested that work makes you free. The livestock races understood little, but the so-called human races, those that still eked a living beyond the flattened suburbs of the great cities failed to grasp any meaning at all from Malarky’s words.

The two cockerel’s named Mo had early on learnt how to peck at each other with their savage beaks. That is how they had understood the verses that had become their scripture. Their chicken folk also took to squabbling and covering their beaks with reassuringly well-fitted N95 masks, and so on.

And then it happened. Some of Malarky’s words were understood as offensive to the two Mos. In fact, I can say with almost complete certainty that they could not have been actually understood in any normal sense, since only an advanced computer from the planet Trefflgum could have had such a capability; and these had not yet made their appearance on the Earth.

Be that as it may, the two Mos ceased temporarily their own struggle and strode towards the pig. They pecked riotously at his legs and trotters, and the upshot was that Malarky fell down, this time to his death, jolting down, bounce, bounce, bounce, one hundred steps down. His plump body traversed the intermediate landings, sped across the corniche, and splashed into the harbor. No one tried to fish him out, and although some pigs can now fly, they had not at this time learnt to swim.

A confederate of Malarky, one who cackled a lot in imitation of a hyena, tried to fill the place of the master orator, but she failed dismally to generate enthusiasm.

And so his first-known appearance on this Earth was a foretaste of his end, like a sea monster returning to the place of its hatching.

Robert Gear is a Contributing Editor to New English Review who now lives in the American Southwest. He is a retired English teacher and has co-authored with his wife several texts in the field of ESL.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast