Our Cat was a Slut

She really was.

My sister got her from the Humane Society, a low cinderblock building across the street from some rusty World War II Quonset huts that were home to auto body shops, a warehouse for repossessed goods, the Crowley Casket Company (the last coffin-maker in the County), and a wonderland known as Weintraub’s Junk where you could buy anything from a U.S. Army-surplus gas mask to a never-used wedding dress that had a story that would never be told.

In Monopoly terms, the Humane Society was right smack in the middle of Baltic Avenue.

My sister called her “Yvette.”

My Dad called her “Sweet Charity.”

We brought her home and she stalked around the kitchen with a sneer on her face like she was thinking, “Whatta dump.”

“She looks like she should be smoking a cigarette,” my Mom said.

“She’s so kyoo-o-o-oot,” my sister said.

My Mom, who got stuck dealing with things like feeding and vets because her kids were too damn lazy to look after their own pets, took her to the veterinarian and I went with.

“Well,” the vet said, “she’s queening. That’s vet-talk for ‘it looks like she’s pregnant.'”

I giggled.

“Jesus, she’s barely out of kittenhood!” my Mom said. “What do you mean ‘pregnant?'”

“I know, I know,” the vet sighed. “They can get pregnant at four months old, on their very first estrous cycle. In fact, a cat can be nursing a litter and still get pregnant.”

“Yvette’s a tribble, Mom!” I said. But Mom wasn’t into “Star Trek.” And this was way back in the good old days when “Star Trek” was still fun, long before it became highly-regarded by critics, celebrated the world over, and painful to watch.

“I can spay her even though she’s pregnant, but you’ll have to bring her back in a day or two—the waiting room is jammed and I’m running late as it is.”

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” my Dad said when we got back to the house. He looked at Yvette and said,

“Tramp! You should be ashamed!”

“OOOOooo, KITTENS!” my sister said, with a big grin.

Yvette must have understood what “spay” meant. While we were putting extra soft towels in her cat bed, she slipped out and disappeared into the canyon behind our house.

She would sneak into our yard to get the food my Mom put out for her, then slink back into the canyon, looking for trouble. We assumed she had her kittens down there somewhere in the foxglove and brambles, and they all grew up as wild as Yvette.

Sometimes we saw one of them running through the yard with a lizard or something I couldn’t even recognize dangling out of its mouth.

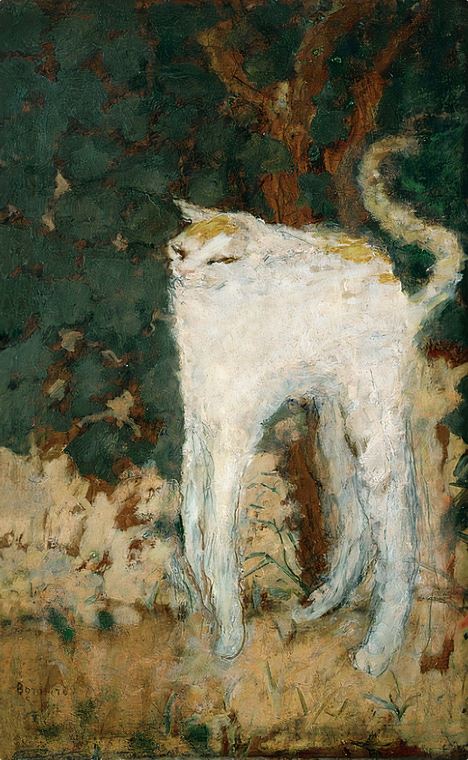

My Dad drew a picture and gave it to my sister.

“I call it, ‘Portrait of Yvette,'” he said.

It was an ink drawing of a cat with dark eye makeup and long fake lashes, wearing fishnet stockings standing under a lamppost, smoking a cigarette.

“That’s not Yvette!” my sister said.

Dad said, “Oh, yes it is. And we gotta figure out some way to find her and get her spayed or the whole neighborhood will be hip-deep in furry sociopaths and tabby nymphomaniacs just like her.”

So off my Mom went to the vet and came back with something in her trunk that looked like it came right out of Torquemada’s rumpus-room.

“The vet lent it to me,” Mom said as she wrestled it into the garage with my Dad. (As usual, my sister and I just stood around watching, snacks in hand.)

“What the hell is it?” Dad said.

“He called it a ‘Live Trap,'” Mom said, lighting up a Kent.

“You gotta be kiddin’ me,” Dad said.

Mom shook her head.

“We put it in the back yard,” she explained, “bait it with tuna, and wait. When we hear it snap shut, we take Yvette to the vet and snip, snip.”

And so, the trap was set up, baited, and left alone to do its work.

When we came out the next morning, we found it upside-down, the bottom wrenched out of it, the tuna gone, and Yvette nowhere to be seen.

“How in the hell did she do that?” Mom said.

“Such is what comes of taking a trollop into your home!” Dad sighed, muttering, “the cunning strumpet.”

Yvette had one litter after another down there in the canyon and

sometimes at night, we could hear them yowling.

“What a God-awful sound,” Mom would say.

Dad said, “The children of the night—what music they make!”

One Saturday everyone was out of the house but me and my friend, Mikey, who was a little peculiar.

We heard a sound in the backyard, an eerie combination of low growling and hissing. We looked out the sliding-glass door and saw one of Yvette’s kittens prowling around.

“Hey,” Mikey said, “I bet we could get it into the house.”

“Think so?” I said. Why I went along with this, I do not know—but it seemed like a good idea at the time.

So Mikey and I got a box of Bugles from the cupboard (a favorite 1960s snack food that probably ended up on a government list of environmental toxins) and started laying a trail of the crunchy little delights from the living room, out the sliding-glass door, and all the way to the middle of the backyard. That done, we scrambled back inside and left the slider open to observe the results of our ingenious experiment.

It didn’t take long.

A lumpy grey-and-white striped kitten popped up out of the bushes and crawled over to the first Bugle. Crunch, crunch, crunch. Then the next one, and the next one, and into the house.

Suddenly, it froze, realizing it was somewhere it had never been before—indoors.

It screeched and puffed up to twice its normal size. Now it was our turn to freeze in terror.

The kitten turned into a grey blur and shot right up the wall, our eyes following it all the way.

When it got to the top of the wall, it started running in circles on the ceiling, making noises we never heard in any horror movie.

Our heads turned around and around as we watched it, our eyes wide and our mouths hanging open. Little bits of the popcorn ceiling snowed down on us as the cat turned into what looked like a big, grey, blurry circle up there.

“Where’s your Dad’s Luger?” Mikey asked.

“You crazy?” I said. “We start shooting holes through the ceiling, the neighbors will complain. And no way could we hit it. Besides, there’s no bullets.”

“No bullets?” Mikey said.

“My Dad probably doesn’t trust himself around my Mom,” I said. (It was not a match made in Heaven.)

“If we could drive,” Mikey said, thinking hard, “we could go to the sporting goods store and get some bullets.”

“Yeah,” I said, “if we could drive and had a car and also had some money, stupid.”

“They probably wouldn’t sell ammo to kids anyway,” Mikey said.

“Right, Mikey,” I said.

“Any Bugles left?” Mikey said.

“I think so.”

Mikey took the box and poured a big pile just inside the slider, then laid a trail of Bugles out into the middle of the back patio.

“Let’s hide behind the couch and watch,” Mikey said.

Sure enough, after a few minutes, the aroma of Bugles got the little demon’s attention and it stopped running in circles and sort of dangled from the ceiling.

It crawled down the wall, sniffed its way to the pile on the floor, and gobbled.

Mikey was elbowing me in the ribs, grinning like the idiot he was.

The kitten started following the trail of Bugles, crunch, crunch, crunch, out onto the patio.

We both jumped up and bounded for the slider, with Mikey yelling, “Close it, close it, close it!”

We slammed it shut, rattling the glass; the kitten didn’t even notice—it was finishing off the pile of Bugles on the patio in huge gulps.

I locked the slider and said, “See Mikey? This is why you’re the brains of the outfit.”

There came a point when we suddenly stopped seeing Yvette prowling around the backyard. And there were no new litters of little Yvettes showing up.

We were sitting in the TV room one evening when I mentioned this to my Dad.

“Yeah, I noticed that, too,” he said. “I think—you know, I think she most likely ran away. Cats do that.”

“Ran away?” my sister said.

“I think maybe that’s what happened,” he said. “Cats do that a lot; they kind of just head off to somewhere new and different.”

“Oh,” my sister said.

Dad got up and said, “You want some ice cream? I’ll be out in the kitchen.” And he walked out.

“I’m sorry Yvette ran away,” I said to her.

She rolled her eyes and said, “‘Ran away’ means skooshed. I’m gonna get some ice cream.”

I just sat there for a minute. Then I got up and went outside. I walked down the street for a couple of blocks, but I didn’t see any sign of Yvette.

I turned at the corner and walked down into the canyon and looked around there for awhile, too.

No Yvette.

I stood there in the canyon, just listening to the wind and the birds and smelling the plants.

A jet flew over; I looked up at the little silver plane and the big, pure-white contrail.

“Please don’t let her be skooshed,” I said, “please. Let her find a family she wants to stay with—inside—and get her spayed.”

Then I walked home.

And, to this day, wherever she is and wherever she went, I also hope that somewhere, somehow, Yvette found true love at last.

And you know what? I hope all of us find safe harbor at last. All of us. Please.