Plausibility as Explanation

by Theodore Dalrymple (July 2018)

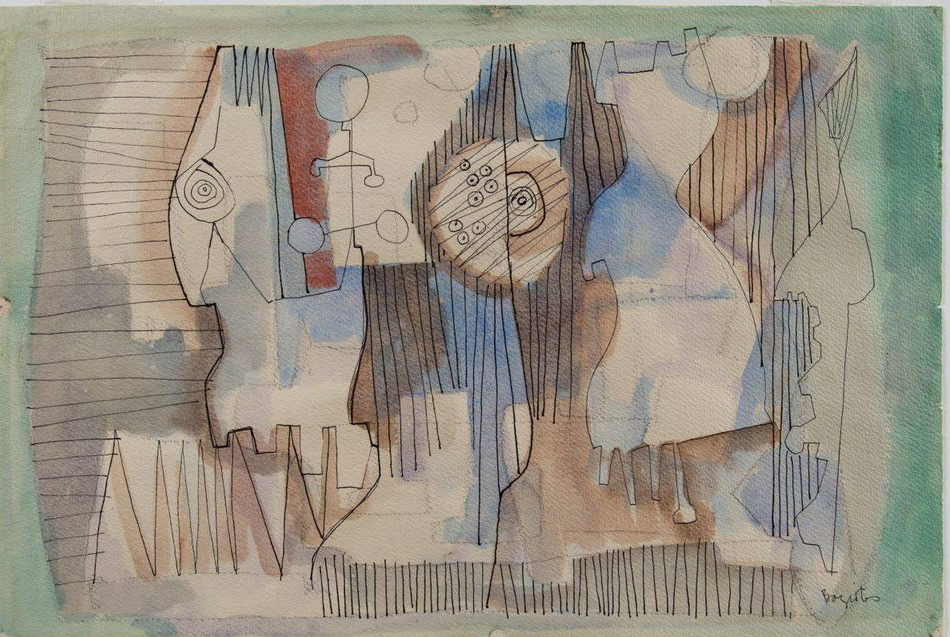

Figures in Smoke #2, William Baziotes, 1947

Whenever a book is described or promoted as a best-seller, I tend not to buy or to read it. Exodus tells us that ‘Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil,’ which I have adapted slightly in my mind to ‘Thou shalt not follow a multitude to read rubbish.’ I pass best-sellers by.

I decided from curiosity to buy The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump: 27 Psychiatrists and Mental Health Experts Assess a President, edited by Dr Bandy Lee, a Yale psychiatrist. It is, or was, a best-seller, though not, I imagine, among supporters of or sympathisers with the President. I suspected, correctly, that it would principally be an echo-chamber for the thoughts and feelings of those who already abominated him.

It was perfectly obvious that the psychiatrists in 1964 were merely relaying their political preferences rather than providing the public with any independent or dispassionate knowledge. In the wake of the fiasco, the American Psychiatric Association, trying to repair the damage, elaborated the Goldwater Rule, making it illegal for a psychiatrist to express an opinion, qua psychiatrist (that is to say with such authority as psychiatry possesses), on the mental health of a public figure whom that psychiatrist has not examined in person, and without his or her permission.

I am not quite sure about the propriety of this rule. It seems to be almost a condition of being a public figure these days that you must be prepared to forego your privacy. Major public figures have their lives sifted as gold prospectors pan for gold, in this case the gold being tiny flecks of scandal that (to change the metaphor) will serve as grist to the mill of his or her opponents and detractors. This is more so than ever before: a single Tweet can destroy a career, as a bad investment can destroy a fortune accumulated over many years. This, no doubt, is an unfortunate development, but it is difficult to see how, in modern conditions, it can be otherwise. A public figure must either be a saint—and even saints are not saintly until they have been retrospectively canonised—or pachydermatous, that is to say so ambitious that they do not mind being denigrated or traduced. In other words, anyone who seeks high office is thereby psychologically unsuited for it, now more than ever before in history. Only in those who have greatness thrust upon them is there any hope.

My main objection to the book was not so much its transgression of a rule of professional ethics, but its profound, though predictable, banality. The fact that it was written by 27 ‘mental health experts’ (whatever they might be) detracted rather than added to whatever authority such a volume might have had. One senses immediately, and in the event correctly, that one is in the presence of groupthink rather than of 27 minds that have independently come to the same or very similar conclusions. To read their contributions is a little like reading 27 copies of the same newspaper to try to establish whether one of its stories is true.

What the contributions do inadvertently expose is the banality of so much psychiatric or psychological diagnosis, which amounts to little more than re-description of easily and publicly observable traits and conduct. Anyone reading the 360 pages of this book will probably come away with nothing new to him, no fact that he did not know before and no opinion that he had not heard before.

We are informed in the volume on many occasions that Mr Trump is as he is because he lacks fundamental self-esteem: that is why he is so narcissistic, he is always trying desperately to compensate for his permanently damaged self-conception. Of course, if he were a morbidly shy and retiring man the same lack of self-esteem would explain it. In effect, then, the same factor explains everything from the grossest exhibitionism to the most profound social withdrawal.

But why does Mr Trump have such low self-esteem that he must plaster himself all over television and the world’s press in order to feel truly valuable, though never quite managing it because the original wound is unhealable?

The answer lies in his father, a dominant and demanding man who was never satisfied with what his son did or achieved, and always wanted more of him. Moreover, Mr Trump’s father was a self-made man in a way that his son could never be. Not only could the young Trump never receive the unconditional or unreserved approval of his father, but he could never equal his achievement, however hard he tried: hence his permanent tendency to self-aggrandisement and also his lack of trust in others. They would always be thinking ‘He is not as good, important, clever, as he thinks he is, or as his father was.’

There is a kind of plausibility to this, but plausibility is a poor guide to explanatory power. It so happens that shortly after I read this book, I read also Anthony Storr’s long essay on Winston Churchill, titled Churchill’s Black Dog, first published in 1969.

Now Storr, a psychiatrist, was a graceful and urbane writer (which the contributors to the collective volume decidedly are not), a psychiatrist with a respectful but not obsequious attitude to ancestors such as Freud and Jung. Indeed, he was more respectful towards them than most psychiatrists would be inclined to be today, but when one reads him one senses that one is in the presence of a civilised, cultivated and intelligent mind.

How does he explain Churchill’s extraordinary career and multiple achievements? Why, lack of self-esteem, of course.

This all sounds perfectly plausible, at least superficially so. In fact, Storr himself exhibited the pattern that he describes. He had a lonely childhood too, deprived of parental warmth; and he too strove for great distinction, never managing to stave off completely a fundamentally depressive temperament by his literary activity, which was of considerable worth, at least aesthetically.

I suppose that the correct way of proceeding would be to choose people remarkable for their achievement or at least their ambition, without knowing anything of their individual biographies, and then investigate whether they suffered distant or disapproving parenting by comparison with a group of controls who were not particularly high-achieving or ambitious, controlling also for as many relevant factors as possible, such as social class etc. This is the counsel of perfection, and in any such investigations such as this would lead only to statistical generalisations rather than to Newtonian-type laws: no one would expect that only those deprived of unconditional parental regard and love ever became unusually ambitious, for humanity is too various to be corralled into a few simple generalisations. In human affairs, exceptions do not prove the rule, they are the rule.

The ultimate vanity of ambition is almost a literary cliché. Gray tells us:

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow’r,

And all that beauty, all the wealth e’er gave,

Awaits alike th’inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

And Shelley:

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

But of course both Gray and Shelley had abusive, distant and disapproving fathers, which caused in them an inordinate desire to write immortal lines.

_____________________________

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast