Reflections on Artificial Nasal Secretions

by Robert Gear (September 2022)

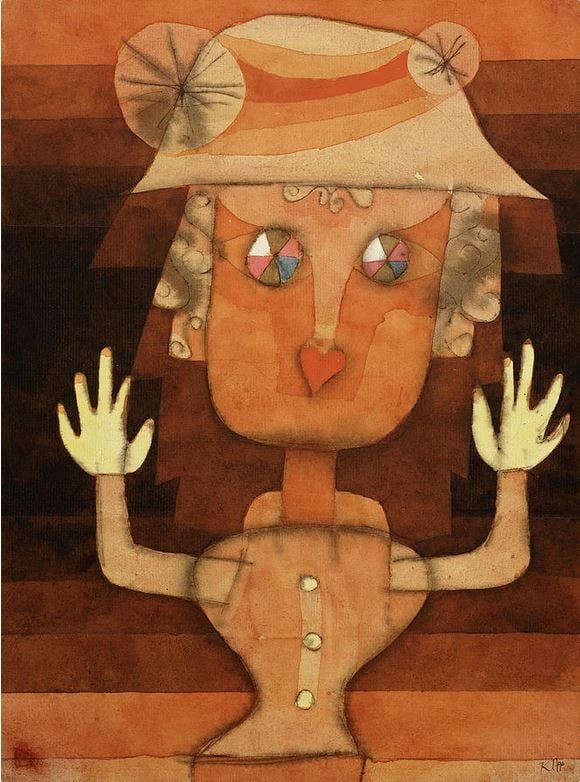

Doll/Puppet, Paul Klee, 1923

Recently, our betters have permitted a slackening of the rules regarding facial coverings (the plural being necessary since two or more layers were often recommended).

This has in turn allowed the exposure of youthful idiosyncrasies such as the various forms of facial adornment temporarily hidden under the medical authorities’ often ruthlessly enforced mask requirements. Or perhaps this is merely a reemergence of an ancient tendency resurfacing in the manner of bell-bottomed leg-wear or Moby Dick.

This has in turn allowed the exposure of youthful idiosyncrasies such as the various forms of facial adornment temporarily hidden under the medical authorities’ often ruthlessly enforced mask requirements. Or perhaps this is merely a reemergence of an ancient tendency resurfacing in the manner of bell-bottomed leg-wear or Moby Dick.

The facial adornments I am considering are those which dangle below the septum of some of today’s youth, centrally placed on the nose, usually symmetrically, although not necessarily precluding asymmetrical projection.

Many years ago, on the first occasion on which I espied a walking illustration of this trend I stood in rapt silence, gazing intently, as Virgil might have put it. And you probably did too.

I have questions regarding the utility or otherwise of such fashionable accessories. First, what benefits accrue to the wearers? The most obvious answer is that the wearer is under the impression that the such adornment marks her out from others of the same age and sex or, as they now say, gender (I say ‘her,’ if pronoun commissars allow it, since the majority of those so bedecked appear to be birthing persons, potentially if not actually).

Do such additions to nasal topography confer uniqueness? That may have once been true of the person or persons who initiated this distinctive approach to acquiring or maiming beauty (which, if the former, must surely be in the eye of the beholder). In later times, this could not have conferred uniqueness since the fashion quickly became prominent on the menu of choices among those seeking to look different with little effort and minimal discomfort.

So the artificial nasal secretions or projections became marks of separateness from the parent strain (such differentiation being an almost universal tendency among youth, a tendency no doubt shared even by many readers earlier in their life trajectory). From original uniqueness, the artificial nasal secretions conferred tribal affinity, and those who sported such metallic adornments could take comfort in knowing that they were not alone. Many others had similar needs. You may be different, but you are not alone!

So the artificial nasal secretions or projections became marks of separateness from the parent strain (such differentiation being an almost universal tendency among youth, a tendency no doubt shared even by many readers earlier in their life trajectory). From original uniqueness, the artificial nasal secretions conferred tribal affinity, and those who sported such metallic adornments could take comfort in knowing that they were not alone. Many others had similar needs. You may be different, but you are not alone!

Does such a trend harm its devotees? I cannot say with any degree of confidence. If the septum is breached in the preparation for inserting the attachment then some minor pain may be felt during mutilation. My concern for the wearer is more to do with how the proboscis extension interferes with the natural need to wipe ones nasal orifices from time to time. What if the wearer catches a bad head cold? Do real secretions mingle with the artificial ones? These are serious questions which I am not in the least qualified to answer.

But what about the larger society in which many of us move while avoiding castoff disposable face coverings and, in some urban areas, spent chewing gum and other testimony of summer nights. There’s the rub, as you might be tempted to say. Is there any joy in it for the casual observer? Spinoza argued, in seeming contradiction to the author of Ecclesiastes (7:2), that ‘there cannot be too much merriment, but it is always good.’ And this fashion trend, as many other trends have and will, spreads mirth in its wake.

Such outward displays of one’s feelings of rebelliousness are not confined to the young, of course, but this ‘demographic’ is naturally more occupied with expressing grotesqueness.

Is this particular attempt to accentuate beauty or strangeness in anywise different from those of the most primitive cultures; those that hail from what we were at one time content to call ‘the uncivilized darker regions of the globe?’ For example, the neck rings of the various African and Asian tribes come to mind. An internet site dedicated to explanation of this mark of tribal affinity coyly states that the rings have an influence on lifestyle. Being made of brass or copper the rings have a tendency to heat up, and also it is difficult for the wearer to lean her head back. And again, note the outmoded use of the pronoun associated with birthing persons.

Is this particular attempt to accentuate beauty or strangeness in anywise different from those of the most primitive cultures; those that hail from what we were at one time content to call ‘the uncivilized darker regions of the globe?’ For example, the neck rings of the various African and Asian tribes come to mind. An internet site dedicated to explanation of this mark of tribal affinity coyly states that the rings have an influence on lifestyle. Being made of brass or copper the rings have a tendency to heat up, and also it is difficult for the wearer to lean her head back. And again, note the outmoded use of the pronoun associated with birthing persons.

And what about lip plates sported by some of the birthing people of Ethiopia? Or the penis gourds (Koteka) proudly worn by some tribesmen of New Guinea and thereabouts. All these cultural significations have an ‘influence on lifestyle,’ somewhere on a continuum between mild inconvenience and foot binding. But just as with artificial nasal secretions, convenience is not part of the equation. Could these and other strange customs make an appearance on the grimy streets of our urban conglomerations any time soon? As Shelley might have put it ‘if artificial metallic snot emerges, can giant lip-plate accessories be far behind?’

And is it even so different in kind from the customs of that foreign country which is our own ancestral past? Strange and wondrous are many of our own extinct or quiescent cultural expressions.

But we shouldn’t delve too deeply into anthropological curiosities since to do so might awaken the wrath of our own privileged wokists. That could truly put their noses out of joint.

Robert Gear is a Contributing Editor to New English Review who now lives in the American Southwest. He is a retired English teacher and has co-authored with his wife several texts in the field of ESL.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast