Sartre and The Paradoxical Notion of Bad Faith

by Samuel Chamberlain (March 2021)

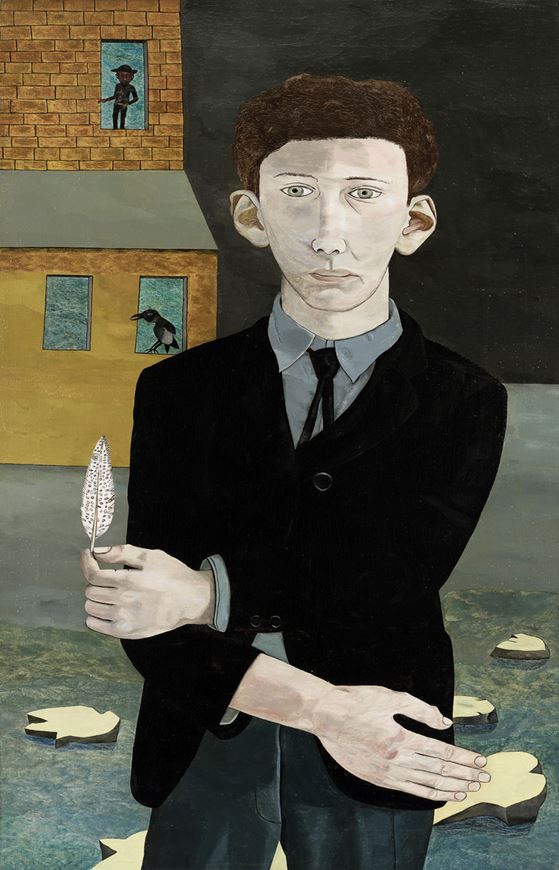

Man with a Feather, Lucian Freud, 1943

In 1943, Jean-Paul Sartre published arguably his most famous work Being and Nothingness. Within the text, he discussed topics such as modes of being, authenticity and transcendence which have formed the foundation of discussion for the fields of existentialism and phenomenology ever since, giving Sartre the title of ‘father of existentialist philosophy.’ One of the most well-known and poignant points Sartre made was that of the existence of bad faith. Despite the utility however of considering the world through this lens in some regards, his own philosophical arguments prohibit any individual from ever overcoming such a condition. In this sense the notion of bad faith is paradoxical and a poor ontological distinction.

Sartre begins his existentialist philosophical claims from a simple ontological premise—that is that objects fall into three modes of being. Either objects are being in-itself, being for itself or being for-others. An object which is in-itself is self-contained and fully realised. A furniture stool would be one example. The stool has no ability to become anything else, it is not affected by its relationship with anything else. Its being is connected to the fact that it is a piece of furniture. Humans on the other hand have the capacity within them to be something other than what they are now—to change, develop and evolve so that they are being for-itself. They have no essence which cannot be changed. They have the power of decisions and autonomy so that ‘humanity really is what it is not and not what it is’.

From this premise Sartre then goes on to assert that all humans have freedom—that we are ‘condemned to be free’. In having no pre-ordained essence we are free to choose what our essence is to be. Sartre gives this freedom three characteristics. Firstly, that the freedom exists until death. Secondly that the freedom objectively exists even if the individual does not want to recognise it. Thirdly, that our freedom is subject to some facticity such as who our ancestors were and what we have done in the past. Humans are free according to Sartre, yet he saw squandered potential, inauthenticity and people rejecting their own freedom.

This rejection of one’s freedom is what Sartre calls bad faith. Bad faith is a paradoxical notion because we know our freedom to be true but wish to protect ourselves from the anxiety and anguish of having to make real authentic decisions, so that “The deceiver therefore is the deceived”[*]. Essentially, the phenomenon lowers the evidence threshold for self-inspection, letting people get away with self-deception. The example which Sartre uses is that of a waiter who thinks of himself as a waiter—his being in-itself—rather than as a person who decides to be a waiter at this very moment but can change that at any other moment—being for-itself.

This is the freedom which Sartre affirms and from his own examples bad faith typically takes two forms—that of emphasising facticity and that of reducing freedom. The first is saying ‘I am what I have been’. An example of this is a poor performing student saying that he can never get good grades because he has always been a poor performing student. The second form of bad faith is that of denying your freedom whilst also claiming transcendence in your decision making. This is where the past and one’s facticity are denied if it doesn’t meet up with the present. An example of this is a criminal thief claiming ‘I am no thief’ despite it being his fourth convicted charge.

The second form of bad faith is where the concept falls into trouble, questioning the utility of bad faith as a useful ontological notion. If one is to not be living in bad faith, they must be sincere and transcendent over the chains of their own facticity. Then that person could claim to have achieved transcendence. But to claim transcendence is to ascribe yourself an attribute, which rejects your freedom and once again you are in bad faith. For example, if the waiter in the previous example was to embrace his freedom and become an author whilst claiming transcendence, he in fact acts again in bad faith as ascribing himself to be an author. In taking your new set of circumstances and then claiming transcendence is to say that your new circumstances are fixed once again. Although your current fixed circumstances are different to the ones you started with, your new fixed standards have led you to be in bad faith.

Therefore, a major criticism of bad faith can come from a pragmatic perspective. If the point of the philosophical distinction is to form categories between being things, then Sartre’s concept of bad faith fails to do that. If all being for-itself creatures live in bad faith, why even bother making a set of categories where one category will never have people ascribed to it? Sartre argued that it was possible to live a life without bad faith, but when the intricacies and implications of his own philosophy are considered deeply, we find it is technically impossible for that to be the case.

As such all humans fall into one of two categories when considering the ideas mentioned above. The first category is the typical idea of bad faith where you either emphasise facticity or undervalue your own ability to act with freedom. The second category is associating transcendence with yourself, and therefore you are also living in bad faith. This is because you are once again ascribing a characteristic (that you do not live in bad faith) to yourself. Therefore, through this technicality there are no circumstances in which humans can live without bad faith due to its paradoxical nature.

Through detailing the ideas of Sartre’s existentialist claims on bad faith, it can be shown to be impossible to live without bad faith as he defined it. The paradoxical nature of the claims calls into question the utility of bad faith as an ontological tool. This is because if the distinction is made to distinguish between those living in bad faith and those not, and yet it is impossible for all people to live without bad faith, then the distinction serves no purpose in the first place.

[*] Sartre, J.-P. (1958 [1943]). Being and Nothingness. London: Routledge Classics. Page 48

__________________________________

Samuel Chamberlain is a political commentator who lives in South East Queensland.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast