Silent Towns

A Monologue

by Evelyn Hooven (April 2022)

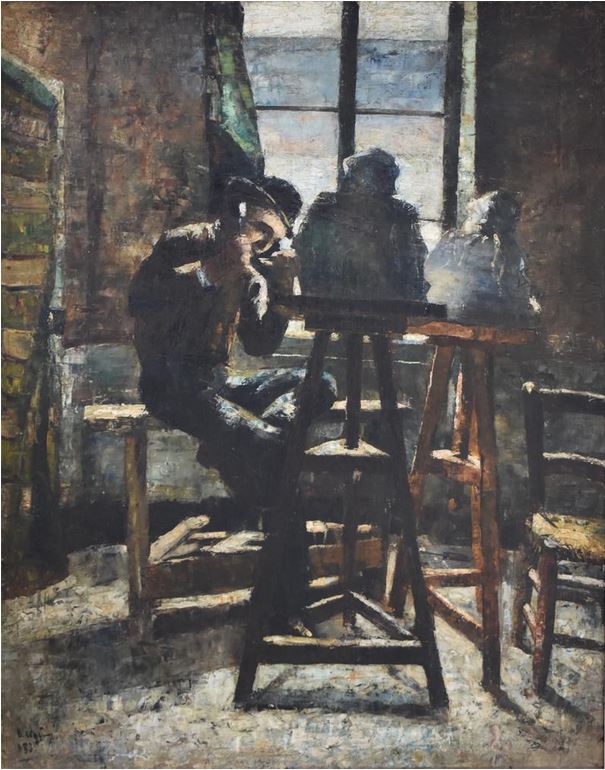

The Sculptor’s Studio Das Bildhauer Atelier, Lesser Ury, 1883

Keith is a painter, sometimes sculptor, in his mid 40s.

++++ “I’m so very sorry.

++++Of course I remember him.”

++++My friend’s father, an elderly gentleman, mysterious, approachable, kind.

++++“I’ll be there.”

++++“No. alone.”

++++The divorce was final, but whatever our status, she would have declined—that funeral too unlikely a networking prospect.

++++In the settlement I lost everything: the studio I designed and built, the house I helped design and build—a home for all our days to come, I’d called it. Her lawyer called it lucky—a property settlement instead of years of alimony. I couldn’t keep retaining a lawyer—so much for representing myself.

++++The tranquility is often welcome. No longer those evening silences, more blight than peace.

++++Lately, though, I’ve longed for the near-harrowing days when my sketchbook and I were inseparable. As the blank canvas stays blank—a painter’s muteness—I feel a pall bordering on danger—no world to live in.

++++I dream of Monet’s gardens, not for the water lilies, lovely though they are, but for the obsession that sustained him, uninterrupted, his right to such vitality for as long as it might last.

++++My gallery owner located this affordable loft-like space with good light and an odd-shaped alcove—a living loft. Twenty years ago this might have been a cause for rejoicing.

++++While the loft was being readied, I visited my home town. I could not cope with the fact of almost not recognizing it.

++++At the funeral I was moved, stirred, for a while pre-occupied with what I’d never before seen: a memorial for an entire town.

++++It would be months before my friend’s father’s own memorial would be unveiled. Next to it a stone for another town, far away in a distant land, a massacre that very few escaped. My friend’s father had been one. The stone was simple, almost stark. The very few who gathered nearby were likely the sole survivors.

++++The stone itself, minimally inscribed as it was, seemed to convey a grief somehow linked to a pledge—to continue remembrance. I was quiet and solemn, even beyond what the occasion called for, at the start of heartbreak.

++++That evening, in my loft, I try—again—to put my books in order. I never needed their company more. I come upon my copy, yellowed, not tattered, of Ode on a Grecian Urn, and read it as though it were brand new and this the first time.

++++I felt that the twenty-five year-old Keats, brimming with poems, thoroughly in love, at the verge of losing his brief life, saw and depicted both void and plenitude, the desolate town and laden urn. The town is “emptied of its folk” to form an elaborate processional. Its inhabitants live on the urn in an eternal present.

++++The weighty and the lighter displacements that had imposed on my mental habitat begin slowly to recede. I start to draw and sketch again. I want to continue. “A friend to man” Keats had called his urn. Art can give that.

++++Yet, when the gallery manager asks for the subject of my next show, I find that I’m not ready.

++++I’ve considered figures from classical mythology’s punishing gods and punished transgressors: Prometheus, Sisyphus, Tantalus. But no. A grand subject perhaps—for another time.

++++What I keep thinking about, without being a memory-lane kind of person, without catastrophe or historic incident, is the numberless towns like my own where the privilege of choice and voluntary decision was tossed away—towns unrecognizable.

Like many Americans I had left the small town of childhood never planning a serious return. And, like many, I casually trusted that the town would always be there and remain itself, a version of home. I never thought that it could be offered, unprotected, to demolition and scarring.

++++The locale, with its thru-routes and malls, had become highway-minded, anonymous. Not on the cosmic historic scale of Rotterdam, Konstantin, Vilna, Saint- Malo—nevertheless lost and missed. I remember Paul Newman—he must have been ill with cancer then—going to New York City to play the narrator in Our Town, Grover’s Corners.

++++As my own town becomes with distance and time more abstract—I imagine a composite of what is every day at risk, of where we can never repair.

++++As I begin to remember what I could not reckon with when I visited last, I find that I’ve had the joy and grief of having known the irreplaceable.

++++I can’t become a crusader against greed, or rebuild what’s lost. And, though not a disaster of world-class order, it’s what compels attentiveness, falls thoroughly to my lot. I can only from memory and thought render it with no pseudo-glorifications: town hall, smaller hotel, reliable green. A composite of what cannot speak for itself, of where we may never, except through longing, return—a hymn to the irreplaceable,

++++The provisional name for my next series of works—Silent Towns.

_________________________________

Evelyn Hooven graduated from Mount Holyoke College and received her M.A. from Yale University, where she also studied at The Yale School of Drama. A member of the Dramatists’ Guild, she has had presentations of her verse dramas at several theatrical venues, including The Maxwell Anderson Playwrights Series in Greenwich, CT (after a state-wide competition) and The Poet’s Theatre in Cambridge, MA (result of a national competition). Her poems and translations from the French and Spanish have appeared in Parnassus: Poetry in Review, ART TIMES, Chelsea, The Literary Review, THE SHOp: A Magazine of Poetry (in Ireland), The Tribeca Poetry Review, Vallum (in Montreal), and other journals, and her literary criticism in Oxford University’s Essays in Criticism.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast