Sink and Swim

by Jeff Plude (January 2019)

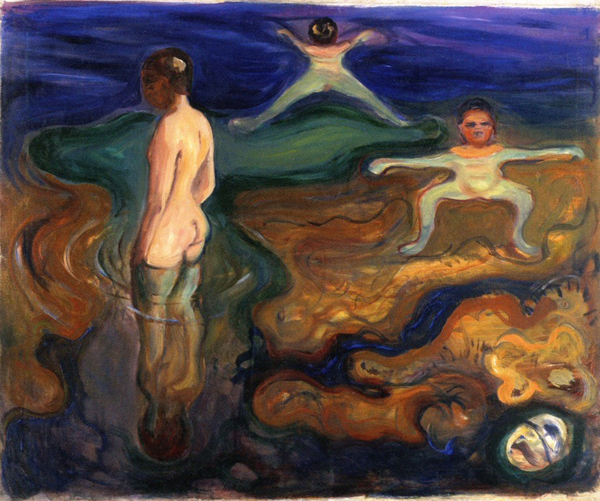

Bathing Boys, Edvard Munch, 1898

It was early summer, the glorious first week between Field Day on the last day of school and sparklers on the Fourth of July. After four months of snow that grew into monstrous mounds, the sun was not just a joy but a miracle.

All of us boys on the block, back when kids would go outside to meet and decide what they were going to do that day, gathered in front of our parents’ modest houses on the village street, canopied with large maples and oaks. It was one of those long-awaited scorching days when my mother would draw all the shades in the house and cover the sofa and armchairs with bedsheets as the worthless window fans puffed out tepid air. But I would be outside all day (so I thought), reveling in the transient sun.

Everybody, meaning the three other boys I hung out with in the neighborhood, was going to the community pool to go swimming. It was too hot to do anything else.

I was furious! And mortified. Why was this happening to me? Why me? Why can’t I swim? Even though I was small for my age, I was a pretty good baseball and football player. I was far from the geeky, awkward, uncoordinated kid who was always picked last or just excluded altogether. Except when it came to swimming.

I was almost ten years old and I didn’t know how to swim. In fact, I was terrified of the water. Neither of my parents knew how to swim, though I had an older half-brother who did, but he was off in the Marines Corps and even when he was around, we didn’t get along. Other than our father, the biggest thing the two of us had in common was stuttering.

My parents saw no great need, apparently, to teach me how to swim since they had maneuvered life’s waves without knowing how to swim themselves, including my father serving in the infantry in the Ardennes during the last days and aftermath of World War II. (I remember my mother telling me about how he’d been thrown in a pool at a party as a prank one time and was humiliated because he couldn’t swim.) But they didn’t take much part in or concern for any aspects of my education, which I don’t think was uncommon in 1971 in the American middle class and wasn’t considered unusual or neglectful, for the most part. For a long time, I wasn’t sure if this was a bad or a good thing.

There was one thing my mother had done: she took me to the nearby community pool when I was about five for a swimming class for mothers and their young children. But it wasn’t really a swimming class, it was more of a get-used-to-the-water type thing. We went a few times. We waded into the shallow end and I remember going underwater to retrieve from the bottom of the pool a stone we’d been instructed to drop into the water. When I came up for air, I was coughing and snorting and my eyes stung. The whole experience backfired and only seemed to make me afraid of the water. I had probably absorbed my mother’s own fear, which seemed visceral, and placed me firmly in the mire of swimminglessness and stranded me there, petrified for what seemed like forever in my child’s mind.

I was not required to swim every day, every week, or any time at all. I didn’t think anything about the practicalities of swimming as a lifesaving skill. I thought only like the little hedonist I was. I thought only of how being unpoolworthy was depriving me of one of summer’s—and especially boyhood’s—greatest pleasures. Perhaps even then I vaguely sensed for the first time the fleetingness of youth, like the short humid summers in the foothills of the Adirondacks where I grew up.

I took things into my own hands, and feet too, you might say. I resolved, just having entered the age of reason myself, to teach myself how to swim. I never dared say it out loud, and certainly didn’t write it down. But I was as sure of my resolve to do it as anything I’d ever attempted.

Over to the pool a mile away I pedaled on my deep-purple bike with the banana seat and chopper handlebars. Perhaps it was the next day after my epiphany. My father wasn’t around much, he worked full time at a mill and the rest of the time, except for a few hours of sleep, remodeled houses. Did my mother ask where I was going? She must have, but what could she have thought when I told her that I was going to the pool? But my mother didn’t think like that. She threw herself into my younger brother, who had been born with Down syndrome not long before our aborted swimming class together, and when she wasn’t tending to him, she was watching soap operas.

Read More in New English Review:

The Buzzwords and BS of American Foreign Policy

Dear Hollywood Celebrities

Baby Steps Toward the Abyss

Maybe that was another reason I decided to attack, rather than drown in sorrow: not only did I stutter, but my younger brother was as different as you can be in this world—not only was he a “mongoloid,” as the awful-sounding word was back then, he also couldn’t walk because of a congenitally dislocated hip—and I guess I could no longer stand being different in any conceivable way. My mother must have thought that somebody else would watch over me and, after all what could she do? She had enough to deal with, as she used to say.

In other words, I knew I was on my own. The internet was still a quarter century away. There was a small public library in town where I read about Homer Price and his uncle’s runaway doughnut machine, but it never occurred to me to ask the librarian about books on swimming. Which is just as well, because it would’ve given me an excuse to pretend I was learning to swim instead of actually learning to swim. In my boy’s mind, I had nowhere and no one to turn to but myself.

At first everything was overwhelming. The sliminess of the cement-block locker room. The swarm of kids splashing and yelling and jumping and running along the sides of the pool on the concrete deck. The diamondy gleam of the turquoise water. The pungent chlorine in my nostrils. The mighty sun beating down in all its power—mocking me, daring me.

I sat on the bench outside the locker rooms facing the pool: my enemy, and at the same time, the medium of my desire. And I watched.

I watched like I never watched before. How did people swim? I couldn’t figure out at first how swimmers were able to kick their feet in the water at the same time they were rotating their arms—it was a mystery. Or, rather, how they managed to stay afloat. Most terrestrial animals, like dogs for instance, which even have a stroke named after them, instinctively know how to paddle, probably because it mimics how they run. But not gorillas or chimps, apparently—primates seem to be the only animals who have to consciously learn how to swim.

But what I did was sink and swim, something I hadn’t considered.

I tried to imitate what I saw the swimmers doing. I sank. I sank like the little rock I had previously been instructed in this very same pool to plop into the clear but unfathomable water (at least to me), the most malleable and intractable of substances, and rescue it from the bottom. And I sank again. And again. And again . . .

After maybe a week or more I managed to stay afloat for a few feet in the shallow end! Each day I went a little farther. I watched the lifeguards’ strokes during the adult swim, when all the kids had to leave the pool for a half hour or so. I started doing the freestyle crawl, raising my head to the side on alternate revolutions of my arms to snatch a breath of air.

Then I graduated to the deep end. I learned to tread water with slow and controlled rhythmic movements of my arms and legs, reaching for the gutter at the edge of the pool when I got tired, and I increased my time little by little up to several minutes. I became friends with two brothers who were a little older than me. They had bodies like Mark Spitz (minus the mustache), whom I would watch win a record-breaking seven gold medals a year later in the Summer Olympics in Munich.

The brothers taught me to do the backstroke, the butterfly, the breaststroke—rather, I taught myself by watching them. That was my new secret weapon: observation. Not just watching, but watching intently, repeatedly. I even dove off the diving board, which struck me with as much fear as learning how to swim. But I was embarrassed and eventually emboldened as I watched a little sun-browned five-year-old there with his large Italian-American family put me to shame again and again as he scampered up the ladder and bounded up and out from the wobbling board and disappeared into a trim little splash.

Consistency was also a big part of my arsenal. As far as I recall, I rarely missed a day at the pool, which was open in the afternoon every day into late August. And the only time I remember not being at my aquatic post, I was far from being AWOL. One day, only the lifeguards and I were there, it was about 50 degrees and gray and eventually started to sprinkle. I was pretty cold in the water, but I didn’t care. I was there to swim. When it started to thunder, the head lifeguard sent me home.

If only I’d kept that kind of will as a grown man.

Read More in New English Review:

Expensive at Half the Price

Does Heaven Exist?

What did Job Say?

I knew that easily could have been me.

I’ve wondered if a how-to book (which is a teacher of sorts) would have helped me learn how to swim. Even as a boy I was already familiar with that nonfiction staple. I had two of them, booklets rather, one on how to be a better football player and another on how to be a better baseball player, by Hall of Famers Bart Starr and Bob Gibson. I don’t recall getting better at either sport because of those books. But my going to the pool every day rain or shine probably came from the idea of an athlete showing up for practice day in and day out, season after season.

Many summers later I heard about The Art of Swimming: Illustrated by Proper Figures with Advice for Bathing, written by a French polymath with the priestly name of Melchisédech Thévenot. Published in 1696, it was one of the earliest books on the subject. Benjamin Franklin, in his Autobiography, says he practiced the “motions and positions” in Thévenot’s manual and even added some of his own (ever the inventor). However, it’s unclear whether Franklin initially used it to learn how to swim, since he says that living near the water (Boston’s Charles River), “I was much in and about it” and “learned early to swim well.” He also had seven older brothers, at least one of whom presumably may have taught him.

John Muir, in The Story of My Boyhood and Youth, also describes how he learned to swim at the ripe age of eleven along with his two younger brothers in a lake near their Wisconsin farm. Their father told them that it was about time for them to learn how to swim but they were on their own—except for a species of local experts whose only fee was close attention. “Go to the frogs,” he said to his sons, “and they will give you all the lessons you need. Watch their arms and legs and see how smoothly they kick themselves along.” Just like me, it took the whole summer for the budding naturalist to become amphibious. (Though one day, dead tired and in deep water, he sank and almost drowned.)

Many things, I believe, are best learned—really learned—by apprenticing. Apprenticing is what I did when I learned how to swim. My “masters” were the good swimmers. This is the natural way to learn how to do something. It’s often the most effective way, too.

Learning by doing may work well for the trades and sports, some may say, but surely not for the higher and more refined arts? But, at least one school of art, the Art Students League of New York in Manhattan, which was founded almost a century and a half ago and whose students have included Winslow Homer and Georgia O’Keeffe, follows the atelier, or studio, method, where participants work under the practiced eye of a master.

My wife, a self-taught painter except for a few drawing classes, attended the League’s open life-drawing sessions on Saturday mornings for more than a year, where she and the other artists sat at easels or with drawing boards and sketched a person posing in the center of the studio while the “master” walked around and commented on or made suggestions for some of the works-in-progress.

In his book What Is Art?, Tolstoy depicts a similar scene in which Karl Briullov, a Russian painter in the first half of the nineteenth century, comes upon one of his students’ sketches and stops to make a correction. “‘Why, you just touched it up a little bit, and everything changed,’ said one of the students. ‘Art begins where that little bit begins,’ said Briullov, expressing in these words the most characteristic feature in art.”

Art—true art—can’t be taught, according to Tolstoy. He says that no school can teach you how to feel, and how to successfully “infect” the reader with that same feeling. And not only that, he says professional art schools spread “counterfeit art” and make the students unable to truly understand the real thing. “As a result,” Tolstoy concludes, “there are no people duller with regard to art than those who have gone through professional schools of art and have been most successful in them.” (Ironically, Tolstoy’s daughter Tatiana entered art school to study painting around the time her father started to write What Is Art?, which he said took him fifteen years to complete.)

In his book Antifragile, Nassim Nicholas Taleb contends that even highly technical skills (like the ones you now need a license to practice) have traditionally been learned not through formal instruction, but apprenticeship. “Take a look at Vitruvius’ manual De architectura, the bible of architects, written about three hundred years after Euclid’s Elements,” Taleb writes. “There is little formal geometry in it, and of course, no mention of Euclid, mostly heuristics (rules of thumb), the kind of knowledge that comes out of a master guiding his apprentices.”

Likewise, it was not uncommon in the past for aspiring lawyers to “read” the law with a practicing attorney. In fact, in four states a person can still skip law school altogether—and the hundreds of thousands of dollars in tuition—and apprentice in a law office for several years instead. Of course, finding such a willing master is likely to prove harder than winning a pro se case. And even if one is found and the bar is passed, an attorney without a law school diploma is certain to face reams of prejudice from the legions of good and equitable doctors of jurisprudence, not to mention society in general.

What about doctors of the flesh? Designing a building or arguing a case in court is one thing, and though potentially devastating, neither requires the practitioner to cut into a live human body, which is, as the psalmist sang, “fearfully and wonderfully made.” According to Taleb, “Even medicine today remains an apprenticeship model with some theoretical science in the background, but made to look entirely like science.”

I know that all those years ago I had no choice in the matter, or so it seemed to me. I didn’t know anything about the value or harm of having or not having a teacher or a book. I just wanted to swim like every other kid on a hot summer’s day. I don’t think I was any kind of wunderkind either. It wasn’t like Caesar burning his troops’ ships so they would either win or die—there were plenty of lifeguards and more summers.

Nowadays, my wife and I try to go for at least one swim a year, usually at a nearby lake. This past summer we spent a glorious August afternoon at a marble quarry in Vermont. Trees framed the grayish white gorge of rock and a hundred or so people, many of whom were kids about the same age I was when I learned how to swim, jumped off the cliffs or simply lounged in the water and on the lower ledge of rock on the water’s edge. It was in the mid-80s, and the water was wincingly cold when I dove in and then soothing as I swam, treaded, floated. I swam the freestyle crawl the 15 to 20 yards to the opposite rock face, rested a bit on the short wooden ladder that leaned against it, and swam back. Over the course of a few hours I swam back and forth several times, climbing out to rest and dry off in my camp chair in the sun. Besides cooling off, it was good to feel the rhythmic motion of my arms and legs propelling me through the water again, my body flowing through it just below the surface.

It’s as good a reason as any to go swimming, even for a middle-aged man.

______________________

Jeff Plude, a former daily newspaper reporter and editor, is a freelance writer. His work has appeared in the San Francisco Examiner (when it was owned by Hearst), his work has appeared in Popular Woodworking, Adirondack Life, Haight Ashbury Literary Journal, and other publications.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast