Social Justice Comes for the Puzzle Page: The Language Police and the NYT Spelling Bee

by Matthew Stewart (December 2022)

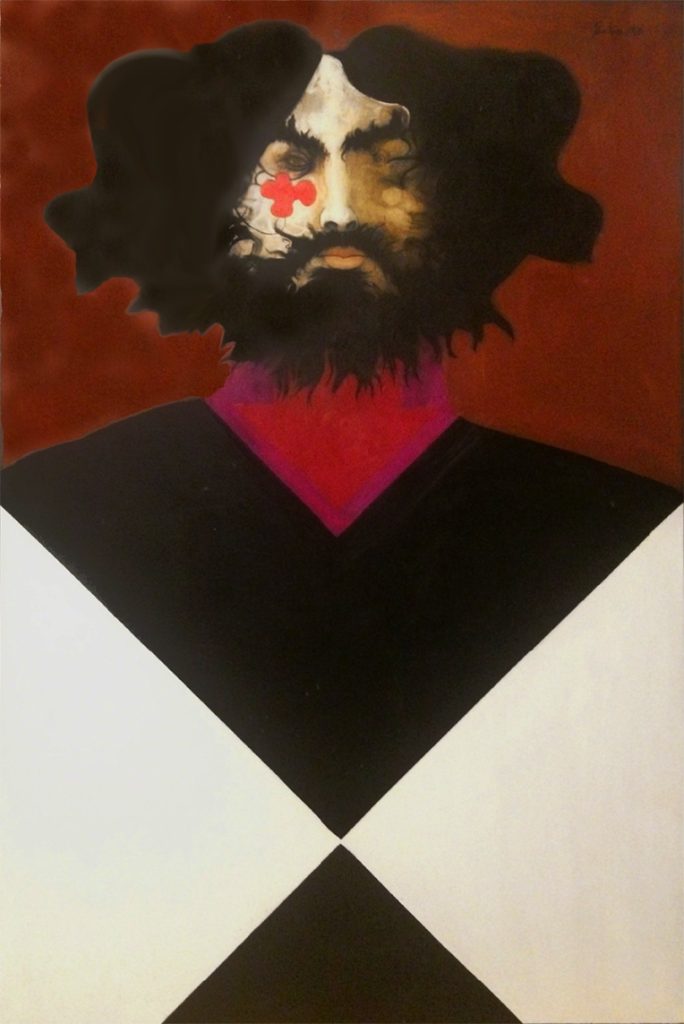

Puzzled Man, Ramon Santiago, 1968

In their hopes to achieve inner order and live a fully ethical life, the ancient stoics strived to tame their emotions in favor of reason. Our age has encouraged a sort of anti-stoic personality eager not only to engage in unreasoned, theatrical emotionality but to display it publically. Woke shibboleths and social justice clichés furnish the content. Such is the age and such is the grandstanding temperament, that even word puzzles cannot escape in-your-face displays of righteousness.

The Spelling Bee is a daily online word game open to subscribers of the New York Times. Players make words out of seven letters presented in the shape of a honeycomb cell. One letter in the center of the comb must be used in the formulated word. The others are optional and can be combined in any way. There is also a “community” comments section that receives upwards of 1,000 posts a day, where players share hints and exchange observations, and–as I found out several weeks into playing the game—at least occasionally take the opportunity to go full woke.

One recent game provided the letters c-h-i-n-k-u-g, with n being the required center letter. To my surprise the words “chink” and “chinking” were both rejected as “not in word list” by the Times’ puzzle master. I played on, creating as many words as I could, before opening the comments section to see what I had missed. It is a regular feature to see complaints that one word or another has not been accepted. These are almost always noted as too specialized or technical to be considered ordinary, “dictionary” words.

So no surprise—one would think–that several posts asked why the word “chink” was not accepted. It is assuredly a “dictionary” word, both noun and verb, known even to those who don’t live in log cabins or wear armor. Cue an onslaught of scolding, shaming and forced incredulity in reply. How could the questioner not know that chink was a racial slur gladly consigned to the linguistic graveyard never to be reborn, original meanings be damned?

Other Times game-players immediately determined that the questioners did in fact know that the word was taboo and only wanted to see it in print in order to inflict pain on Asian-American game players. Why miss an opportunity to assign evil motives to an honest question? The outré souls who had the temerity to reply by noting the dictionary’s primary meaning for the word or by citing literary examples were accused of gas lighting.

Having long ago heard interpretations of conservatism that aligned it with mental illness, I had sworn that I would never account for the politics or morals of those with whom I disagreed by labeling them with a psychiatric malady. But it was impossible not to conclude that the community comments section for Spelling Bee attracts more than an ordinary distribution of cluster B personality types. The hive mind appeared floridly unbalanced.

Emotional histrionics, impassioned hyperbole, moral showboating, baseless accusation, leaping to conclusions—every sort of rhetorical excess furnished its own bright orange highlighter. Questions asking why the word was not accepted were typically a simple sentence or two long. The replies which ensued overwhelmed the queries, often sermonizing at length, only to end by asking why those who implied that the word ought to count were making such a big deal of the issue. And let us think for a moment what demographic is most likely to spend its time on the Spelling Bee. Surely we are talking about middle-aged people and up, with plenty of retirees, one would think, and very few woke university students.

The very sight of the word, it was claimed, would be harmful, unsafe, flashback-inducing, ruinous. The obvious fact that anyone who looked at the letters c-h-i-n-k had already seen the word was assiduously ignored. So was the fact that “chinking” was also disallowed despite the fact that Spelling Bee regularly accepts gerunds and participles, as indeed it did with other words on the day in question.

To argue against the word without using the word presented a problem for those proclaiming taboo. Some commenters used workaround phrases such as “a certain disallowed word.” Others resorted to typing c***k, the three asterisks magically removing the pain of seeing the letters h-i-n. Even while supporting its righteous exclusion, other commenters nonetheless typed the word out in full, presumably without sending anyone to dial the Samaritans. Many are the internal contradictions of language policing.

Above all what came through was the refusal to think clearly, consistently and reasonably about potentially hurtful slurs. Clearly context and intention are all important in such cases. The context here is a word puzzle: benign and neutral grounds. The intention is equally obvious: for players to have fun and exercise their brains. Yet, rather than recognize the nonthreatening situation, taboo enforcers turned logic on its head by claiming that the word must be taken in its ugly sense barring evidence to the contrary. The word is guilty until proven innocent.

As if they were addressing a child saddened by the loss of a favorite toy, the censorious repeatedly pointed out that there were plenty of other words to create. One sees here the actual gas lighting, the imputation that defending the normal was equivalent to provocation. As Joanna Williams has said, “Woke refers to the side in the culture war that denies it is waging a culture war, yet which repeatedly fires the opening salvos.”

No discussion emerged about the many other similar words of dual denotation, even though such consideration is obviously implied. What, for example, to do with the words spade, monkey, cracker, slope, guinea, bitch, faggot, or fairy? These words and many others have all been used as slurs, yet retain legitimate, even indispensable, uses. Following the censors’ line of argument, all such words would have to be banished from Spelling Bee. And if they must be banished from Spelling Bee, mustn’t they also be forbidden for all word games?

Indeed, what is special about word games? Why would games present a special case open to censorship while other appearances of taboo words would not? Taboos are absolute after all. The censors’ claim to censorship rests upon the syllogistic assertion that some words can be used as slurs, that slurs can cause pain, therefore slurs must not appear in print or be uttered aloud. If that were case, mustn’t the words be banished in toto?

Why stop there? What of homophones? If chink is to be banished, then by that logic, so should fairy be forbidden. And since ferry sounds like fairy won’t it too cause pain to some who hear the word? Where would this slippery slope end? If their pain-potential is the basis for banning words, then could not the next level of censorship extend to words that cause pain by association? Think, for example, of concentration, camp, slave, ship, chains, whips, closet.

The hundreds of words spilled in defense of censoring the word “chink” did not contain any such thinking-through of consequences. Instead the puzzle pages of the New York Times provide one more venue for the morbidly irrational to exercise their morals in public.

Matthew Stewart has written on social and cultural affairs for venues including City Journal, Law & Liberty, Quillette, and Spiked Online. He is the author of Modernism and Tradition in Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast