Stalin’s Architect: Book Review

by James Stevens Curl (August 2022)

Stalin’s Architect: Power and Survival in Moscow. Boris Iofan (1891-1976), by Deyan Sudjic

ISBN: 978-0-500-34355-5, 320 pp., many b&w & col. illus. Hardback £30.00 (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2022)

Boris Mikhailovich Iofan (1891-1976) was born Borukh Solomonovich Iofan (the surname Iofan is a variant of a more common Jewish name, Jaffe) in cosmopolitan Odessa, where 35% of the population was Jewish. It is unsurprising that it was in Odessa that the Zionist Movement took shape, spurred on no doubt by the horrifying bloodshed in October 1905 following the Potemkin episode. Russian Jews at the time had been obliged to adopt national naming conventions, assuming a surname (which was not part of Jewish tradition), and had very restricted access to higher education. Indeed Russia’s vicious anti-Semitism seems to have prompted Iofan’s change of name and his adoption of militant secularism. His parents were moderately prosperous, and gave their children the benefit of education: both Boris and his brother Dmitry (1885-1961) became architects.

Young Boris trained first at the progressive Odessa Art School, and then moved to St Petersburg in 1911, where his brother had attended the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts (which supervised the Odessa establishment), and worked there for a time during which the new Imperial German Embassy designed by Peter Behrens (1868-1940), was erected (1911-13) under the supervision of Ludwig Mies (1886-1969). ‘Mies’ means seedy, poor, rotten, lousy, wretched, bad, awful, crummy, and out of sorts, although the cuddly, pussycat (which would be Miez, Mieze, or Miesekatze in German, with the ‘z’ pronouced ‘ts’), soothing sound in English appealed to Modernist enthusaists when referring to the German architect. In 1921 Mies became Miës van der Rohe, so when the ë is pronounced, a sound something like mee-es results, which has no associations with what is nasty, ugly, dismal, or vile in either Dutch or German, and the ‘van der’ sounds vaguely grand as well as reassuringly Dutch. The Embassy’s ‘icy self-control, intimidating presence, and unmistakable projection of power would provide material for the most sober of Boris Iofan’s classical buildings designed in the 1940s’ (Fig.2).

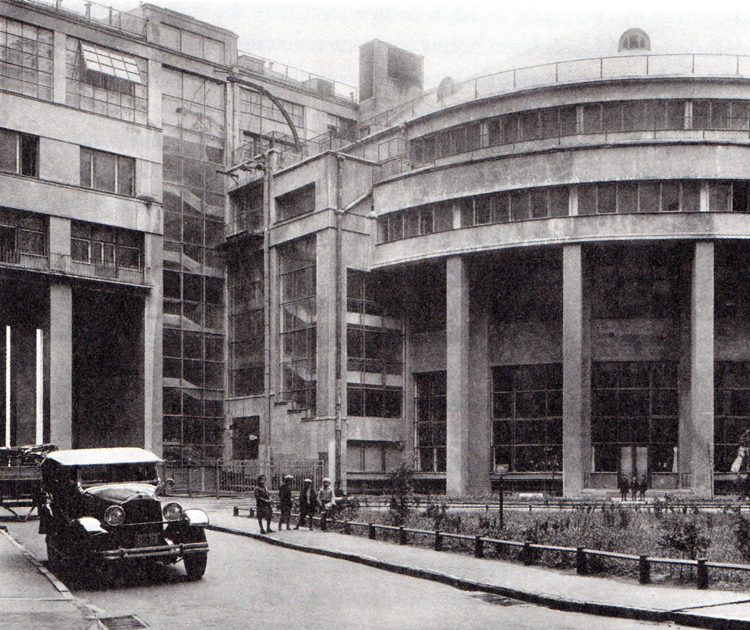

During his time in St Petersburg, Iofan mixed in the same circles as other architects who would dominate the profession after the Revolution. Gifted Jewish students were accustomed to study abroad because of the discriminatory quota system in Russia, so many went to Germany or Austria, but as tensions between Germany and Russia rose, Iofan chose to continue his architectural studies in Rome, luckily leaving just in time to avoid being conscripted into the Army and enrolling to study architecture in the third year at the Regio Istituto Superiore di Belle Arte, where he absorbed much of the Classicism espoused by the establishment at that time, a Classicism that was to re-emerge in his later career, transformed by adopting a megalomaniac scale to almost outdo the sort of thing produced earlier by Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728-99). Iofan was to remain in Italy for ten years, and joined the newly formed Italian Communist Party in 1921: he also met his future wife, Olga Sasso-Ruffo (1883-1961), though at that time she was married to Boris Petrovich Ogarev (1882-1956), a playboy Tsarist Cavalry Officer turned businessman. Iofan’s rise as a significant figure in Soviet architecture really began when he designed the Soviet Embassy in Rome (1922-3), and, under the ægis of Aleksei Ivanovich Rykov (1881-1938), returned to Russia where he made his career. This was an important connection, for Rykov was appointed Chairman of the Council or People’s Commissars (i.e. effectively Premier) after Lenin’s death in 1924, and backed Joseph Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, aka Stalin (1879-1953), against Lev Davidovich Trotsky (1879-1940), though he had no illusions about Stalin’s thirst for dictatorial powers. Aleksei and Nina Rykov became close friends with the Iofans, and indeed neighbours, living in the massive Bersenevskaya Embankment (1928-30) apartment-block, which incorporated shared facilities such an a laundry, shops, and a cinema (Fig.3): the northern front, facing the river, owed much to a severely stripped Neo-Classicism (Fig.4), and the building marked Iofan’s emergence as a major figure in the Moscow architectural scene, managing to survive the various terrifying purges and ‘liquidations’ that marked the blood-soaked career of the Soviet dictator. Other residents of this huge complex included Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (1894-1971) and Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov (1896-1974).

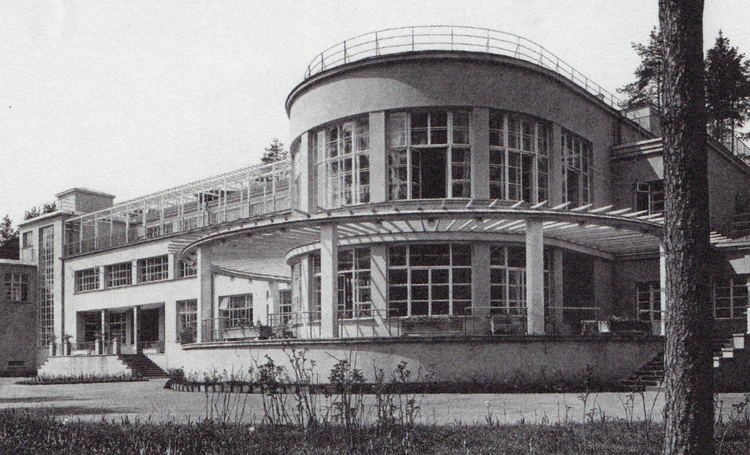

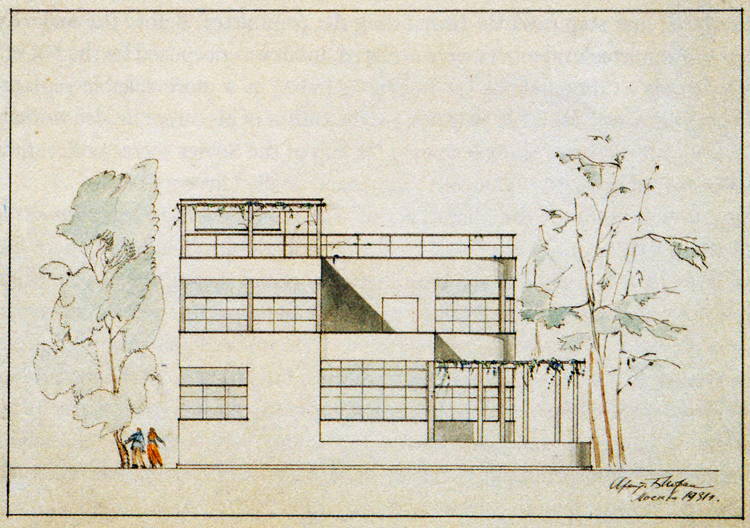

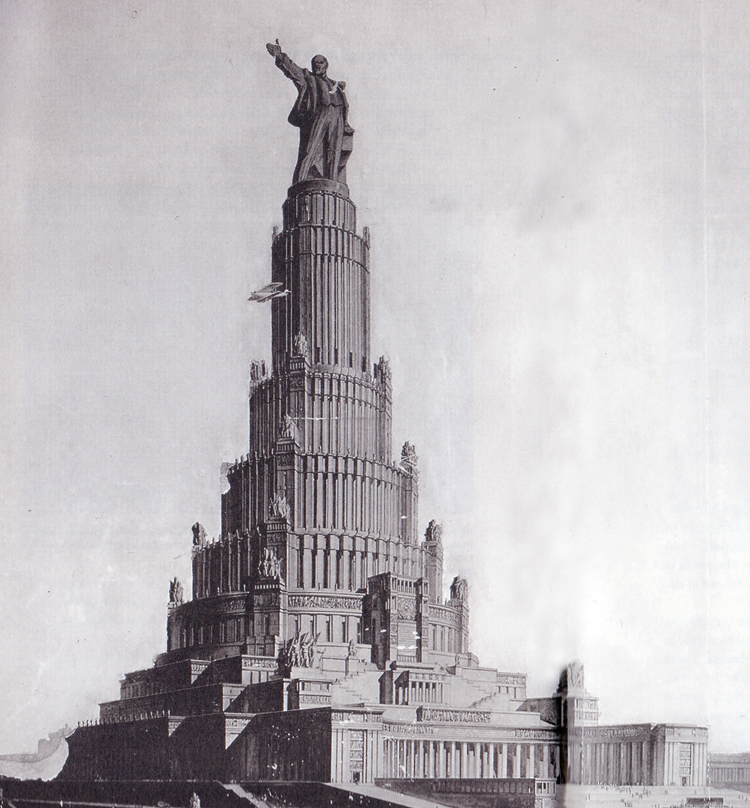

In the 1920s, Iofan’s work included the Sanatorium at Barvikha (1929-34), intended for the exclusive use of senior Communist Party members: with its steel-grid balconies, steel windows, and white concrete frame, its style lay within the mainstream of European Modernism (Fig.5). A design for a villa from the same period could easily have stemmed from the drawing-board of many contemporary Western Modernist architects (Fig.6). But the lightness, even elegance of such designs was in stark contrast to what became Iofan’s most famous, but unexecuted work: the huge project for the Palace of the Soviets (1933-8), produced in collaboration with Vladimir Alekseyevich Shchuko (1878-1939) and Vladimir Georgiyevich Gel’freykh (1885-1967). This was to be a truly massive, monstrous thing, topped by a gigantic statue of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, aka Lenin (1870-1924). Intended as a synthesis of architecture, sculpture, and the decorative arts, the design signalled the institutionalisation of a simplified Classicism, hugely inflated in scale, as the official style of the Stalinist dictatorship (Fig.7). This design emerged as the result of an international competition: among eager Western entries were those by Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, aka Le Corbusier (1887-1965), and Georg Walter Adolf Gropius (1883-1969). Le Corbusier and his apostles, enraged and outraged he did not win, created a great fuss when the results were declared, but Gropius, undeterred, entered another competition for the Reichsbank organised by another poisonous totalitarian State.

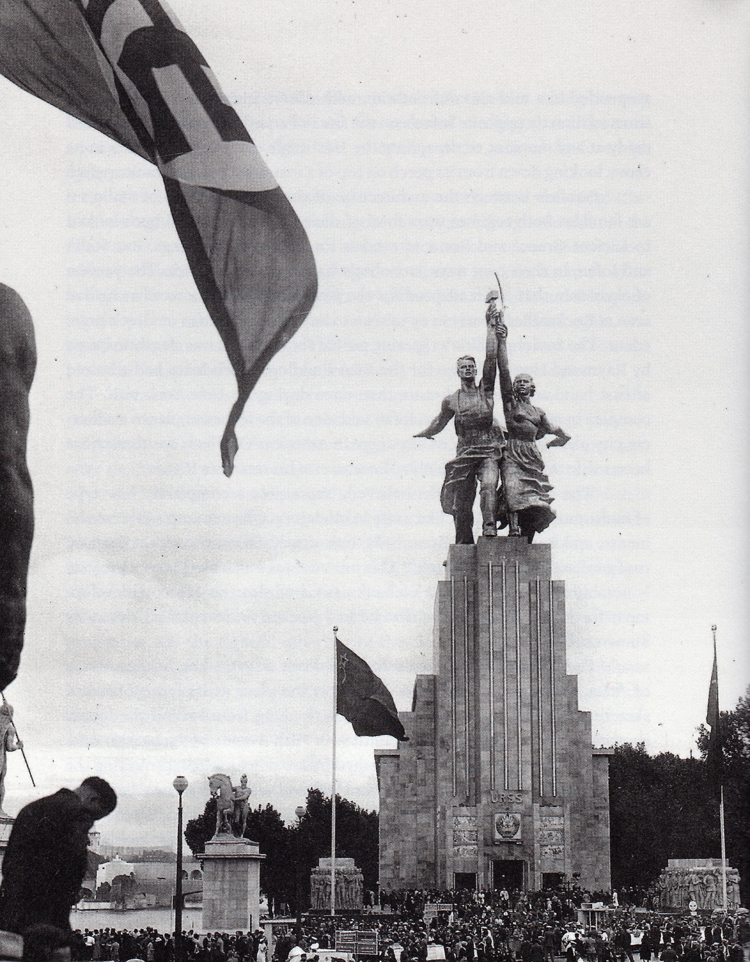

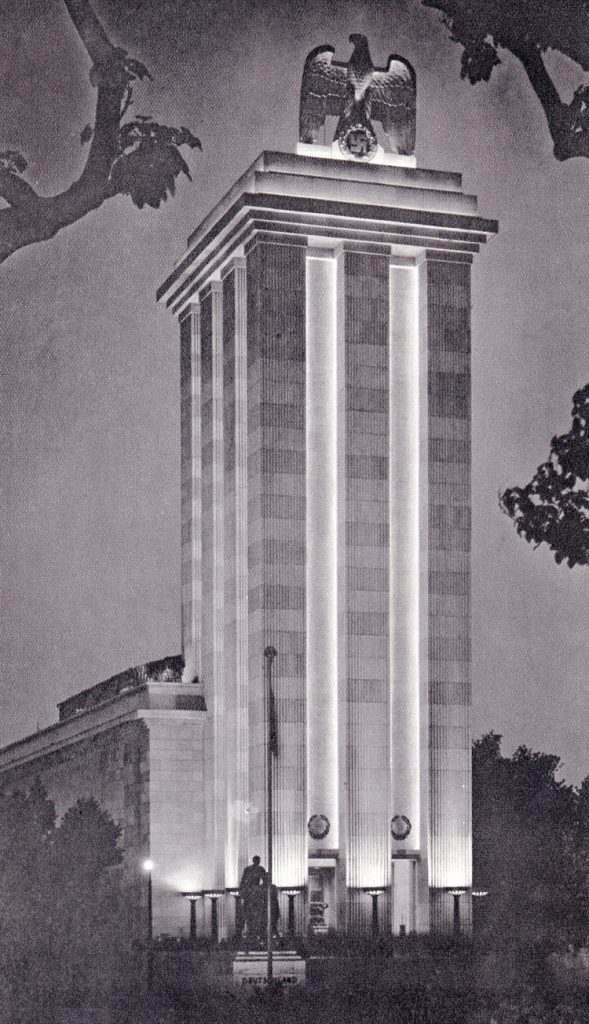

Iofan’s Soviet Pavilion, for the Paris Exposition of 1937, had a stepped tower at one end supporting two enormous figures, a factory worker and a kolhoznitsa, personifications of industry and agriculture, marching together towards some marvellous imagined future: the male figure held a hammer in his left hand, and the farm-girl a sickle in her right (Fig.8). As Sudjic observes, the two figures ‘would spend almost six months suspended in a mid-air confrontation with the German Pavilion, situated directly opposite … on the site in Paris (Fig.9). The Soviet sickle looked ready at any moment to decapitate the Nazi eagle clutching a swastika in its claws, looking down from its perch on top of a massive … pylon.’ In fact, the impressive eagle, by Kurt Schmid-Ehmen (1901-68), clutched a hefty wreath surrounding a swastika (Fig.10), and the German pavilion was designed by Albert Speer (1905-81), using a simplified Classicism that had already been apparent in works by Behrens and, later, Paul Ludwig Troost (1879-1934), and which owed much to ancient Greece (Fig.11). Parallels are often drawn between the architecture of National Socialism and that of Stalinism: both régimes favoured using native stones, but Iofan was also influenced by American architecture, and his Paris Pavilion was not entirely innocent of themes drawn from the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center, New York (1931-40), designed by Raymond Mathewson Hood (1881-1934). The German Pavilion was static and solid, but the Soviet Pavilion was far more dynamic, seemingly surging forward (Iofan likened it to a ship), with the stainless-steel ‘Worker and Collective Farm Woman’ figures, by Vera Ignat’yevna Mukhina (1889-1953), the Soviet Union’s foremost Socialist Realist sculptor, leading the charge at the prow (Fig. 12).

Sudjic’s book is a useful introduction to Iofan’s life and work, although one might wish the text had been more carefully edited, for there are many repetitions, and the illustrations are sometimes a bit murky: there could have been more of them as well. And endnotes are an abomination: why publishers insist on them, rather than have user-friendly footnotes, is beyond comprehension. I sometimes think publishers must hate readers to inflict endnotes on them, which are a pain to use.

Eric Blair, aka George Orwell (1903-50), was to note that ‘certain half-arts, such as architecture, might … find tyranny beneficial, but the prose writer would have no choice between silence or death.’[*] Indeed, and for Iofan, the most prominent of Stalin’s architects, the patronage of a paranoid, murderous dictator came at serious personal risk, but rather than not build at all, he was prepared to design what Stalin demanded. Miës van der Rohe also attempted to snuggle up with the National Socialist Terror State and only left for the USA when rich pickings were offered across the Pond. Iofan had to keep flowing a continual stream of praise for Stalin’s genius, closing his eyes when Stalin set his torturers to apply ‘special measures’ to Rykov, his erstwhile patron, neighbour, and friend, who, unsurprisingly, confessed to ‘many crimes’, and was shot for his pains. Shortly afterwards Nina was also shot, and Rykov’s daughter, Natalia, spent the next 18 years in the Gulag, finally freed and found a job as a schoolteacher by Khrushchev. In 1949 Iofan was denounced for his ‘decadent bourgeois values’, and for ‘hampering the development of the architectural sciences by continuing to grovel before’ the bourgeois models of the USA, Paris, and Rome. The Iofan family believed that Stalin had Iofan’s name removed from one of the notorious death-lists complied by the terrible Lavrenty Pavlovich Beria (1899-1953) on the grounds that the architect might still be ‘of some use’ to Stalin and his circle.

As Sudjic writes, the second half of Iofan’s career ‘is a cautionary tale of how damaging it can be to come close to political power, especially for an architect negotiating an accommodation with tyranny’. Starchitects, their tongues hanging out with avarice as they smarm all over oligarchs, dictators, and every disreputable kind of horror holding capacious moneybags, are odiously familiar today. Architecture can often be an instrument of statecraft, and can serve international conglomerates, vile régimes of various kinds, the whims of dictatorial individuals, and all interests holding financial or political clout. There is no doubt that Iofan was a talented architect, whose reputation has suffered because of his identification with the grand projects of the USSR, in which a stripped, vaguely Classical style predominated, a style associated with a totalitarian dictatorship. Speer’s work, too, has associations that have damned it: his own position in the upper echelons of National Socialism, and his equivocation regarding his own part in the excesses of that ideology’s mere 12 years in power, have besmirched him.

If you sup with the Devil, you need a VERY long spoon.

[*] George Orwell (2000): ‘The Prevention of Literature’ in Essays (London: Penguin in assn. with Secker & Warburg).

Professor James Stevens Curl is the author of many books, including The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture (with Susan Wilson, 2015, 2016), Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism (2018), and Freemasonry & the Enlightenment: Architecture, Symbols, & Influences (2022).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast