by Larry McCloskey (March 2023)

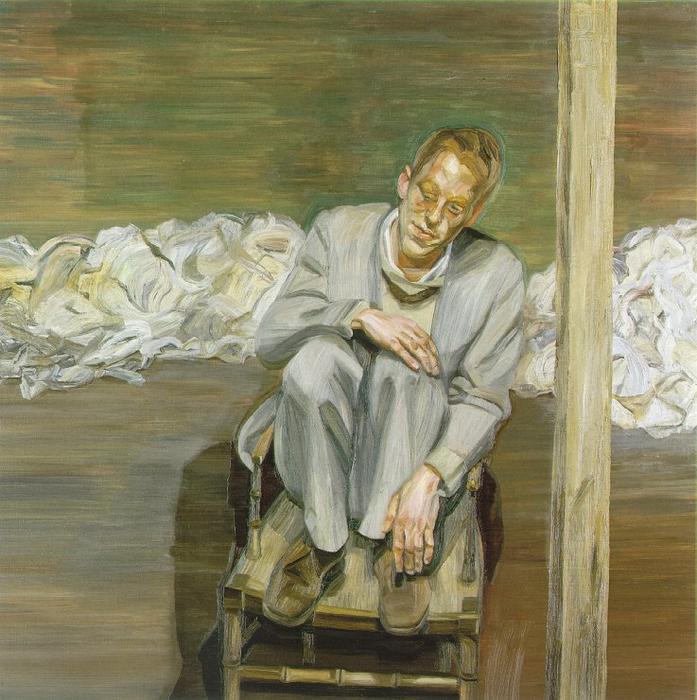

Red Haired Man on a Chair, Lucian Freud, 1963

When I was a graduate student, I got a job to make a buck. Not knowing what to do with my first graduate degree (and in truth it had no utility), I continued to a second, hoping that academic abstraction would somehow crystallize into career clarity. It did not, and my yearning for a purpose and a career continued.

Meanwhile, completing back-to-back graduate programs takes time, and I had to find some menial labour to keep Kraft dinner on the table. I would certainly have qualified, but it never occurred to me to apply for a student loan. I am grateful it never occurred to me. In fact, I’m eternally grateful that many of the ideas that hold the world giddy with utopian possibility never occurred to me. These would be the same ideas that are wreaking havoc with young people who are simply trying to figure where they fit, if they fit. The word used today is inclusion, but that concept as generally understood is not the notion of fitting in we all crave and need.

Difficulty fitting in because of one or a multiplicity of exterior parts (intersectionality) may have some relevance, but is not the substantial missing piece. I know this goes against progressive orthodoxy and is subject to immediate cancellation. The problem with the primacy of exteriors is in going too far it doesn’t go far enough. Our various features do not add up to our essential being. We are more than the sum of our parts. (Just what do you think Martin Luther King meant when he pleaded for recognition of the content of our character? Clue: it was not a call to apply any of the various isms out there). Going further requires going deeper, where character either resides or has been eroded by a thousand mindless distractions.

I grew up in a flawed, somewhat repressive Irish Catholic family of nine. Still, for all its limitations, we understood two central facts of life: 1) This life and what we do in it is not primarily about me, myself, and I. 2) No one is ever going to make our way in this world for us. If that sounds harsh, it was neither a call for the abnegation of self nor formula for social isolation. We knew our parents loved us, and in the heavily populated shared quarters of all space in our tiny bungalow, isolation simply had less opportunity than today. Yes, social isolation is more complicated than this—social media and technology being major drivers of what divides us. Still, it reminds true that the enforced simplicity, scarcity, and frequent boredom of then offered some protection against many of the drivers of loneliness and poor mental health today. As a minimum, close quarter misery in a neighbourhood of like families generally prevented us from thinking our experience was unique enough to qualify as loneliness. In fact, much of our motivation to embrace the world, risks and all, was a hunger to experience something that had a whiff of originality outside our clan.

It’s true we ran with wild, un-Covid like abandon through the neighbourhood unbeknownst to our parents—who certainty erred on the side of too little parental oversight. Seven kids will do that. Still, is the only-child grilled every evening by two eager parents fascinated by every reluctant detail about nothing in particular better off? Parents then and now generally tried their best, but something fundamental has changed, and for all the emphasis on self-esteem as a value today, the rise of anxiety and depression is frightening. How is it possible for all that caring to fall so flat?

Back to my necessity for low pay, menial labour. Out of my buried-in-the-middle-of-seven-kids upbringing came a desire to be useful. I’d been the family dummy, the only of our motley crew not to skip a grade. I barely got by, with the prospect of having to repeat a grade always a possibility. So, to compensate, I accumulated the most credentials in a family where everyone graduated from university. But university courses and degrees were never going to satisfy needing to be useful. In fact, these were likely contributors to feeling useless, which we all are until we become useful. Not a modern thought. Truisms tend to have this in common.

I got a job as an orderly on the spinal cord unit of the rehabilitation centre. I was untrained, was given no training, and had a full workload of patients with complex needs in the first five minutes of my first shift. It was not, was not even distantly related to the easy and irrelevant academic world I was working to pay for. And I loved it.

The work was physically demanding—try doing a one-man transfer of a recently injured and highly vulnerable 250-pound quadriplegic with a 130-pound runners physique. The work was psychologically demanding—the patients, overwhelmingly young adventurous guys, could have been any of us, if not for the grace of God. If not for the grace of God became my mantra, and gratitude for what I learned became a reality far greater than anything I’d ever learned at university. And being Catholic and Irish, I felt guilt for feeling gratitude for the life my brothers and I were spared having to endure. Why these beautiful and vibrant teenagers on high school graduation night, and not any of the risk-takers from our wild bunch? A disquieting thought for which there were no clear, easy answers. It occurred to me that expecting clear, easy answers is not the answer. Actively doing felt much better than angst-ridden rumination, and that was answer enough. So, I immersed myself in the work, often pulling double shifts, present for every heartfelt moment, in stark contrast to my absence from class as I finished my second graduate degree.

Recently, I wrote a book about what I learned, and more to the point, the issues that personal extremity and catastrophic life events raise about life and our purpose in it. Mostly, these people—many who have died, always too young—continue to inspire, haunt, and pervade my dreams. A single sentence from Inarticulate Speech of the Heart, will suffice: “A young guy who had roared down country lanes on his motorcycle in the liberating spring after a Canadian winter lay imprisoned in a room with three other spinal cord patients, windows shut to keep the summer from seeping in, with a novice unwanted stranger doing unwanted strange procedures, who would walk away in carefree fashion at the end of his shift.”

Before I vacated the university, I volunteered with the Coordinator for the Disabled. Though I had no time, it was serendipitous timing. He was leaving for a bigger disability-related job and asked if I would take over. I did and we compared notes on how to best serve our constituents every week for several years. We became friends and would have been lifelong friends if not for the fact he died. He was a quadriplegic and died of liver cancer, age 37, and I continue to feel his loss all these decades later. Still, I was able to name our centre in his honour in founding the Paul Menton Centre for Students with Disabilities, in 1990. I’ll summarize the ensuing useful decades with a quote by Kahlil Gibran: “work is our love made visible.”

Being needed was what I needed, and in doing so I got over me, myself and I, for an identity dependent on many people, independent of none, and still indisputably mine. The irony being it takes many people to develop the cognitive diversity of one. Work did not define me, but passionate work in the service of others allowed for dispassionate reflection, and over time, the chance to develop core values unrelated to the ideological flavour of the month.

Ideology is borrowed thinking, and the indoctrination of ideological causes and expectations on young people in the name of progressive education is a pernicious virus for which there is no vaccine. Even as education outcomes and standards plummet, kids are directed towards proper, non-thinking conformity over critical, diversity of thinking, and we are coming apart at the seams.

Covid exasperated ideological narrowing, but it was well underway before the Great Reset opportunity. Even progressive people can see that as a population young people are not doing well, lacking more than the buzz word ‘resiliency.’ Could it be that force-fed causes—wringing hands about climate hopelessness, finding new and weirder ways to tattoo and pierce towards uber-individuality just like everybody else, protesting rights without a thought to responsibilities, disparaging history without knowing it, and cancelling any whiff of the political other—ain’t working out?

I generalize it’s true, and it is also true that many young people are thriving. Still, what is in the air is more than an impression. Consider this: the National College Health Assessment conducted by the American College Health Association, has asked students to self-assess their mental health for decades. The percentage of students who self-assess as having poor mental health has steadily risen over the decades from single digital to a disturbing 47% for women and 46% for men in 2019, to an inexplicable 76% for women and 66% for men in the reset rebirth year of 2022.

I do not want to over-simplify a complex problem. But perhaps too, my use of the word inexplicable is misplaced. Some things are explicable. Young people might fare better with a dose of reverse progress. If left to figure out their views on the seriousness of the world without ideological expectation, they might be less anxious. And to become a bit less serious, they might employ the world’s best antidote to depression. I speak, of course, of the use of humour in the company of real human beings. (Never mind that my three daughters and their three daughters wish I had the emotional regulation to hold back some of my most corny zingers. I tell them, and sometimes even believe it is for their own good.)

Most of all this: what’s behind the curtain? Education without outcomes, progressive politics, fidelity to the proper causes do not give life meaning, and surely mental health remains inexplicable unless one confronts the crisis of meaning that is bigger than climate change, Covid or Justin Bieber.

Einstein’s pro-offered choice is appropriate here: “There are only two ways to live your life. One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle.”

Fading faster than unfashionable history in recent years has been mystery and wonder, transcendence and any notion of God. God is most troubling for many contemporaries (scientific materialism run amok), because in the midst of chaos and ruin, we like to think we’ve got it figured out. Or if not, in a rare concession, that science will figure it out soon enough. (Think Edvard Munch’s The Scream that progressives think is just a temporary lack of mindfulness). And because we don’t admit to the disparity between what we know and how we strut about not knowing, we suffer self-injurious hubris.

I get asked, especially from young people, for the answer. I usually begin by admitting I don’t know the answer. Then, depending, I might suggest we think about it, and talk about it again another time. Until then, maybe we can go for a walk and maybe if you’re lucky I’ll remember a couple jokes, and you can tell me about that girlfriend possibility you mentioned the other day. And, if in walking, we end up at the soup kitchen, it wouldn’t hurt for us to take up the ladle and help out for awhile. The people there are interesting and funny. They’ve all had tragic lives but most don’t live their life tragically. I don’t know how they do it. What was that we were going to talk about later? Doesn’t matter.

A bogus scenario, a trite distraction, a feigned attempt at instilling purpose. All true and pathetically so, I suppose. Still, there may be method in my madness for a world that capitulates to ideological madness at the expense of the mental health of its most vulnerable members.

Table of Contents

Larry McCloskey has had eight books published, six young adult as well as two recent non-fiction books. Lament for Spilt Porter and Inarticulate Speech of the Heart (2018 & 2020 respectively) won national Word Guild awards. Inarticulate won best Canadian manuscript in 2020 and recently won a second Word Guild Award as a published work. He recently retired as Director of the Paul Menton Centre for Students with Disabilities, Carleton University. Since then, he has written a satirical novel entitled The University of Lost Causes, and has qualified as a Psychotherapist. He lives in Canada with his three daughters, two dogs, and last, but far from least, one wife.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

Very good. I especially like the Einstein quote. I rarely have any younger person ask me for advice. But I like your tactic. It reminds me of a psychiatrist who talked of counseling a patient: “And all we talked about was fishing! But he got better.”