The Art of the Gimmick

by Peter Dreyer (June 2022)

Angelus Novus, Paul Klee, 1920

“What is conceivable can happen too,”

Said Wittgenstein, who had not dreamt of you;

—William Empson, “This Last Pain”

In early 1972, I was expelled from Greece, where I had lived for five years, by a military junta that had seized power. Not wishing to return to my native South Africa in an era of aggressive apartheid enforcement, I chose to go to America. As Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana puts it: O Fortuna imperatrix mundi! (O Fortune, empress of the world!) In New York, I found myself riding a leap tide of good luck. I’d written a satirical little spin-off of Thomas De Quincey’s “Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts” titled “The Future of Treason,” which I mailed to Coburn Britton’s magazine Prose. A week or so later, almost unbelievably, by today’s standards, Britton called me. “I loved your piece,” he said. “I’d like to publish it. We can pay you $500.”

With my worldly wealth thus doubled, I travelled across the continent, and at a coffee shop in San Francisco’s North Beach later that year, I met Robert Briggs, who would became my friend and literary agent. “Why don’t you write your autobiography?” Briggs said. “Give me a one-page outline.”

With that in hand, he called Ballantine Books in New York to pitch the idea.

“What’s the title?” the Ballantine editor asked. We didn’t have one, but glancing at the outline, Briggs’s eye fell on “The Future of Treason.”

“The Future of Treason,” he said.

“Great! We’ll buy it!” the Ballantine editor said.

Ballantine offered an advance of $3,000, and how could I quibble? I could live for six months at least on $3,000. The contract Briggs negotiated gave me just three months to produce the book, and I sat down in Berkeley with a borrowed typewriter to come up with the 60,000 words agreed on. The Future of Treason duly came out in paperback in 1973—with the title and my name in a noose on the cover. That made me queasy—not so much the noose as the nonsense.

I tell this tale merely to illustrate the power of a phrase. I was an unknown. My life story wasn’t remarkable, my pseudo–De Quincey squib wasn’t all that witty, and The Future of Treason isn’t a particularly noteworthy book.

But that title had a touch of magic; it reached out and grabbed attention all by itself.

***

I had been reading Heidegger’s Being and Time, and I quoted a line from it as an epigraph in The Future of Treason: “The loss of all hope . . . does not deprive human reality of its possibilities.”

But I myself had never for a moment lost all hope, and what did Heidegger mean by that anyway? Was he agreeing avant la lettre with Camus’s suggestion that suicide—which losing all hope must surely suggest–may be the only serious question in philosophy?

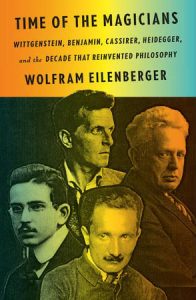

Of Wolfram Eilenberger’s quartet of “magicians,” only two pass muster: Heidegger and Wittgenstein. Eilenberger himself concedes that Cassirer was no wonder worker, calling him a “thoroughly decent man and thinker … but not a great one,” the only one of the four men “whose sexuality never blossomed into an existential problem [sic—but this is gossip!], and the only one who never suffered a nervous breakdown”; in all, “a radiant symbol of a liberal, republican attitude.” He was too quotidian, too nice to be a magician.

And Walter Benjamin was a magician only posthumously. No live magician could have been so consistently unfortunate, for it is, of course, the business of magicians to be lucky. Only a select few valued Benjamin during his lifetime. He would hardly be in Eilenberger’s book but for his unpredictable ascent, post mortem, to the status of academic icon on the wings of “an enormous Anglo-American industry of post-structuralist and postmodernist interpretation.”[1]

Heidegger was launched as a young professor by his terse title Sein und Zeit (1927). Who could not but be interested in those two great components of our lives, Being and Time? How much more attention-grabbing a title than, say, Das Erkenntnisproblem in der Philosophie und Wissenschaft der neueren Zeit, that of Cassirer’s magnum opus. And if you then found yourself immersed in over 500 pages on issues such as “Dasein’s Authentic Potentiality-for-Being-a-Whole, and Temporality as the Ontological Meaning of Care,” confirmation bias had probably already committed you to the notion of Heidegger as an up-and-coming philosophical sorcerer, what with profundities such as “death is the constant condition of the possibility that can be concretely grasped … In other words: Death is the portal to freedom.” And then, too, if you were German, there was also Heidegger’s engaging political correctness. In 1933, as rector of Freiburg University, he told his students: “Let not theoretical principles and ‘ideas’ be the rules of your Being. The Fūhrer himself and he alone is the German reality and its law today and in the future.”

“[Hannah] Arendt would say that Heidegger did not have a bad character, in fact he had none at all,” Eilenberger says. Unforgivably, he cites no source for this that I can see. One wonders in what context she said it, and what she might precisely have meant. Character, after all, has been defined as determination of purpose, and Heidegger was undoubtedly very determined in his prime purpose, which was taking care of No. 1, as people used to say and perhaps still do. But Heidegger, a married man and a father, had seduced “the good Hannah” (in both the philosophical and sexual senses) when she was his nineteen-year-old student, and she grew up to be a woman who thought the evil represented by the likes of Adolf Eichmann “banal.” So she might have had a different definition in mind.

Wittgenstein who claimed to be seeking to “show the fly the way out of the fly bottle,” and thus rescue philosophy from “the bewitchment of our understanding by means of language” (something practiced by philosophers above all down the ages), proceeded to double down on precisely that bewitchment with gnomic wisdoms such as: “The world is everything that is the case” and, most famously, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent.”

Unless they are honest illusionists like Houdini or the Amazing Randi, who strove to expose frauds, magicians necessarily, albeit sometimes perhaps unconsciously, practice the art of the gimmick. Outside of Camelot and comic books, magicians tend to be tricksters or televangelists. In Wittgenstein’s case, the gimmick was inscrutability. At Cambridge (England), he was the Buster Keaton of analytical philosophy—the great stone face. And yet there were so many cracks in it. A multimillionaire, he’d given his fortune away, but not to the poor, to his own wealthy siblings. He opted to teach school as a utopian exercise of sorts, but had to quit after he knocked out one of his pupils with “two powerful disciplinary blows, not with unusual violence” (emphasis added), whose foster-father called him “inhuman” and an “animal trainer”; the boy died, of leukemia, they said, a few years later. A “peevish sourpuss,” he overawed well-bred British colleagues with his sheer rudeness and mad stare, insulting a hostess who’d asked what he’d like for dinner by telling her, “I don’t care what I eat as long as it’s always the same.”

Bertrand Russell and G. E. Moore had, however, declared Wittgenstein a genius. Keynes had too. “God” the Bloomsbury cognoscenti called the Austrian philosophical wonder boy, and no one had the nerve to second-guess them and ask, “But why hasn’t he got any clothes?” Wittgenstein had come to England from his Italian POW camp and shown his manuscript to Russell, the story goes, asking him to judge whether he was a genius or an idiot. If he was a genius, he said, he’d do philosophy; if he was an idiot, he’d become an aviator. Depriving the budding airline industry of a notable recruit, Russell answered wrong.

Wittgenstein is a tragic figure. “[I]t was shame alone that kept him alive,” Eilenberger asserts, somewhat gnomically. For all their great wealth and sophistication, the Wittgensteins were not a happy family. Three of his brothers committed suicide. Told by his doctor that he was dying (at sixty-two, of prostate cancer), Ludwig evidently muttered, “Good.”

***

In her essay for the New Yorker in 1968 introducing him to American readers, reprinted as the introduction to a collection of his essays titled Illuminations, Hannah Arendt asserts that although Benjamin “thought poetically,” he was “neither a poet nor a philosopher.”[2] He particularly grasped, though, the way language is able to fix itself in human cultures in poetic images that grow more potent with the passage of time. Creating such images—listening for them, if I might put it that way—is what a poet essentially does. In The Tempest, Shakespeare sketches the outcome:

Full fathom five thy father lies,

Of his bones are coral made,

Those are pearls that were his eyes.

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

We may remain oblivious of the innumerable poetic “thought fragments”—from the Bible, Shakespeare, and other poets from Homer on—embedded in the English language, but they are our tools for thinking about the world. Arendt quotes Mallarmé’s description of poetry as a sort of big brother who settles the outstanding debts of language (I translate very roughly). A great poet can express the most unpalatable thoughts and make them sound somehow hopeful. “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow, / Creeps in this petty pace from day to day, / To the last syllable of recorded time; / And all our yesterdays have lighted fools / The way to dusty death,” Shakespeare has Macbeth say, and I’ll be darned if there’s not something positive there!

Benjamin sought to compose a book consisting entirely of brilliant citations, so precisely placed that they served to back up and extend one another. “Quotations in my works are like robbers by the roadside who … relieve an idler of his convictions,” he said. Perhaps his most famous flight of fancy is his interpretation of a painting of Paul Klee’s titled Angelus Novus—for Benjamin, “the angel of history,” gazing backward into the past:

Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skywards. This storm is what we call progress.[3]

He killed himself at the age of forty-eight in September 1940, only a few hundred meters from the Spanish border he was seeking to cross to escape the Gestapo. It was the era, Arendt notes, of “the still intact Hitler-Stalin pact whose most feared consequence at that moment was the close co-operation of the two most powerful secret police forces in Europe.”[4] Benjamin and some fellow refugees had been turned away by Spanish border guards, who rejected their visas, and, having lost all hope, he took a lethal dose of morphine during the night. The Spanish police are supposed to have relented soft-heartedly because of his suicide, allowing his companions to proceed the next day to Portugal and eventual safety. More likely there had simply been new instructions from Madrid about how to handle refugees’ visas.[5]

***

These, then, are supposed to be the representatives of philosophy’s “great decade”?? How great could those ten years after World War I really have been anyway? Greater, say, than the 390s BCE , when Socrates taught Plato, with the teenage Aristotle waiting in the wings? Or the 1670s, when Leibniz visited Spinoza for an exchange of ideas? In science and in ethics respectively, those two arguably played a significant part in the making of modernity—which was, after all, a well-established phenomenon by 1919, and certainly by the time of the Davos conference in 1929 at which Heidegger and Cassirer tussled to such leaden effect over neo-Kantian morality.

Benjamin, a bit of a Marxist, contemplated joining the German Communist Party, mostly as a career move, but didn’t. Heidegger, more than a bit of a Nazi, resembles nothing so much to me as the man from Belgrave in the limerick who kept a deceased sex worker in a cave and justified it as an economy measure—you know the guy I mean. Wittgenstein remains the enormous blank he elected to be. Cassirer moved to America, needless to say, where he wrote a book titled The Myth of the State and died in New York at seventy.

Entertaining though Eilenberger’s anecdotes are, and based on an impressive reading list, the intricate web he weaves is, I fear, an artificial, journalistic one. The four men had little in common and would probably not have cared to be in a room together. Benjamin hated Heidegger; Wittgenstein must surely have despised him (as he did pretty much everyone); Cassirer would have grimaced and borne it, as at Davos. For Heidegger, the clincher would have been that the other three were all Jews. The tales assembled here are, moreover, not exactly what Baudelaire had in mind when he said, “Who among us has not dreamt, in his ambitious days, of the miracle of a poetic prose? … supple and resistant enough to adapt itself to the lyrical stirrings of the soul?”[6]

Hitler knew best, Heidegger told his students. To paraphrase Mr. Peanutbutter in Bojack Horseman, What did the Führer know? Did he know things?? Let’s find out! “Lucky are those who have the happy knack of being able to forget most of what they have been taught,” Hitler is quoted as saying. “Those who cannot forget are ripe to become professors—a race apart. And that is not intended as a compliment.”[7] Professor Heidegger survived the slight by almost a quarter of a century, living to be eighty-six. His family treated him to a Catholic burial.

Perhaps I should take another look at Illusions. Sorry! I mean, of course, Illuminations.

[1]Martin Lilla, “The Riddle of Walter Benjamin,” New York Review of Books, May 25, 1995, www.nybooks.com/articles/1995/05/25/the-riddle-of-walter-benjamin.

[2] Arendt in Benjamin, Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 4.

[3] Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” IX, in Illuminations, 257–58.

[4] Arendt in Benjamin, Illuminations, 1.

[5] Franco was, believe it or not, rather less than keen to fall in with Hitler’s desires. If he had been, and had, for example, allowed the Wehrmacht to pass through Spain and take Gibraltar, sealing off the Mediterranean to the British Navy, the Nazis would surely have won the war.

[6] Baudelaire, Spleen de Paris, cited by Benjamin in “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” in Illuminations, 165.

[7] Quoted by Norman Cameron in Hitler’s Table Talk, 1941–1944 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1953), August 1942.

Peter Richard Dreyer is a South African American writer. He is the author of A Beast in View (London: André Deutsch), The Future of Treason (New York: Ballantine), A Gardener Touched with Genius: The Life of Luther Burbank (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan; rev. ed., Berkeley: University of California Press; new, expanded ed., Santa Rosa, CA: Luther Burbank Home & Gardens), Martyrs and Fanatics: South Africa and Human Destiny (New York: Simon & Schuster; London: Secker & Warburg), and most recently the novel Isacq (Charlottesville, VA: Hardware River Press, 2017).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast