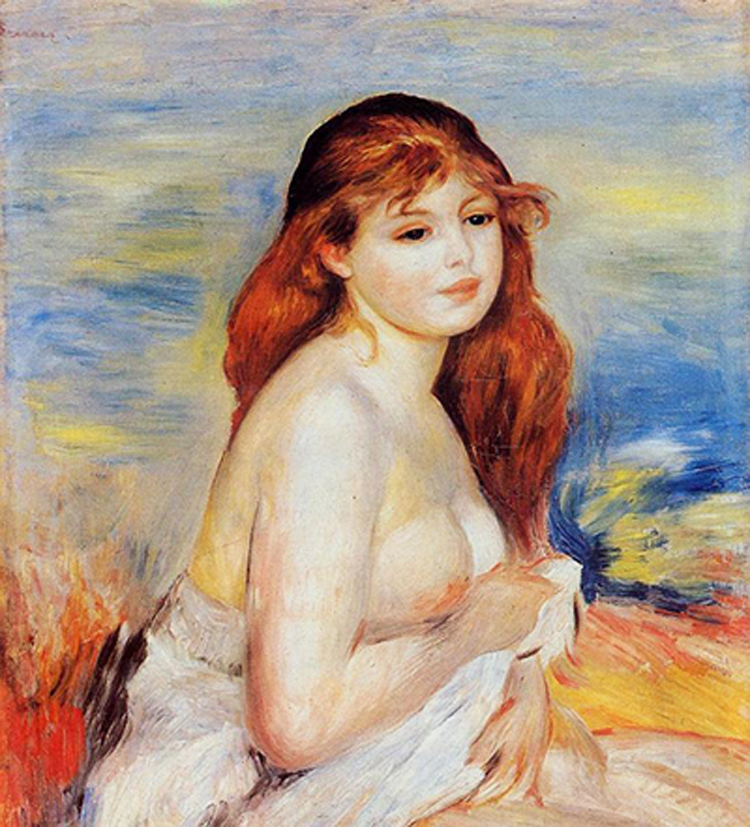

The Bather

by Armando Simón (July 2021)

Bather, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1890-95

The museum of art had received on loan from another museum in another country a very nice collection of Renoir paintings. They were on exhibit to the public and had been displayed for the better part of a month. The exhibit had, of course, been publicized, which publicity had resulted in a greater than average attendance. Although art lovers had attended faithfully, there had been also the curious, as well as those individuals who attend whatever is publicized, as well as those individuals who felt that they had to attend in order to maintain (in their own eyes as well as their acquaintances’ eyes) the self-endowed title of Intellectual.

Among the curious had been Carlos Centeno, a tall, muscular man in his thirties with a prominent nose. He had gone the first weekend because, upon being exposed to the advertisements and, upon reflection, he had realized with embarrassment that he knew nothing about Renoir paintings, or for that matter, any kind of art and that constituted a gaping hole in his knowledge. Therefore, he decided that this would be a good opportunity to at least give it a try. He dragged along his recalcitrant wife who was in no way interested in art, nor, as was the case with many Cuban women, was she ashamed in the least bit about her total ignorance (they had long ceased to see eye to eye on many things).

The effect was unexpected, to say the least. The paintings totally transformed him. He became completely, totally enraptured with them and would gaze at each one with awe and fascination. It was as if these particular masterpieces had awakened a dormant receptor that had heretofore been present all along, dormant, but to which he had been oblivious as to its existence. Each canvas struck a hidden chord in him. When his wife, bored, had nagged him sufficiently to induce him to leave for home, he did so reluctantly, but not without buying a book at the museum store on the life and artwork of Renoir. He read the whole book at one sitting, although it was way past midnight when he finished.

He returned the next day, Sunday, and was one of the first to walk in when the doors opened. And he was one of the last to leave.

Centeno returned every day thereafter without failing to marvel at the canvases. He would do so directly after work and stay on until closing time, which was about an hour afterwards. Sometimes he would take off early from work, sometimes not, after first calling his wife to let her know that he would be coming home late.

Whether it was a scene depicting a village or barges on the Seine, a crowd of people or a pastoral scene, the effect was the same: it was as if he was magnetized. Yet, their effect was nothing compared to the effect upon him by one particular masterpiece in the collection. It was of Renoir’s Bather, showing a nude redheaded young woman.

By today’s standards of what is beautiful, the model would be considered to be a bit too plump, but to Centeno she was the most beautiful woman that he had ever seen, either alive or in images. It would be no exaggeration whatsoever to state that he literally fell in love with the redheaded bather. No, not the painting, the bather. It was literally love at first sight. To many of us who have never before seen such an occurrence, it may sound bizarre, but the same has indeed happened before to other unsuspecting viewers with other masterpieces of art and to both men and women.

Suffice it to say that Centeno was enthralled by Bather and would spend most of his time viewing it, going to other frames, then returning to it as if he was viewing it with a fresh perspective. She was exquisite.

As he gazed on it, he would wish, secretly, that he could somehow possess such a vision of loveliness.

His five-year marriage had deteriorated in the usual pattern. He was still fond of his wife but she, for her part, had turned sometimes cold, sometimes distant, sometimes loving, sometimes hostile. He often wished for a return of that boundless love that had been present during the first year of married life. As he spent more time viewing Bather, the more this nostalgic yearning grew.

One day he decided, upon reflection, and feeling a bit guilty, that lately, this past week, he had ignored his wife and would, to make up for it, go home early and take her out to a restaurant, followed by dancing. She would like that.

Instead, he arrived home to find her naked in bed with another man.

Centeno went berserk. He seized a small wooden table by the leg and broke it over the man’s skull. Still holding on to the table leg, he bludgeoned the potbellied man into senselessness and continued doing so, breaking all the man’s ribs, his legs, jaw, nose, arms. Then, seeing his wife in the state that she was in, naked, covered with the man’s sweat and hair, he lost what little self-control he had left and gave her the very same, equal, treatment that he had administered to him. When he was through, she was equally mangled and broken. Her face alone was a swollen, purplish mass, matted with blood that could still be recognized as supposing to be a face. Just before he left, he gave a parting kick to the groaning man.

He drove around the city for a long time, though he was not conscious of his surroundings or of the time passed. It was as if he was driving on automatic pilot.

He came to, parked at the museum’s parking lot. Like a somnambulist, he got out of his car and entered the museum. The staff was surprised to see him there, coming in so late, it almost being closing time.

He walked around from painting to painting, pausing briefly before each. At most, he felt a vestige of that elation that they had previously evoked in him. He now saw them as paintings, illusions, and not visions.

He came across Bather. The woman’s hair was brilliantly red, her skin fair, her face childlike pretty in a decidedly woman’s body and his previous yearning broke out once more, mixed with pain and anguish. He wished that he would be in possession of such a vision of loveliness and of love.

He felt hot, dizzy and perceived himself to be swaying back and forth.

Next day, within minutes of the staff arriving at the museum, the discovery was made. Someone had defaced one of Renoir’s paintings, the Bather, and the shocking act was widely reported in the news. The host museum’s staff was embarrassed and apologetic—nothing of this sort had ever happened before—and extra security was hired at once to prevent copycat acts. The lending museum’s staff, on hearing of the defacing a few hours after the announcement, was furious and unfairly blamed the recipient museum’s staff.

The surveillance cameras did not provide any clues.

It turned out that the defacing had been done by painting in a figure, that of a man, into the canvas itself and this was what puzzled everyone for several days. To do so, in the amount of detail that the intruding figure had been painted in, the time element would have run into hours and the culprit would have been discovered by the patrolling guards (who were all given a polygraph test). Nor was the painting a substituted fake. Then, the mystery deepened as, upon closer inspection, it became noticeable that the second figure was in the same style as the rest of the painting, and, that the brushstrokes were confluent with the other, original, brushstrokes. The intruding figure, incidentally, was that of a tall man with a prominent nose gazing lovingly and tenderly at the redheaded bather; in his eyes there was undisguised, boundless, adoration.

No one ever found Carlos Centeno again, nor was he ever heard from.

__________________________________

Armando Simón is the author of Very Peculiar Stories and A Prison Mosaic.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast