The Gentile Problem: A Work in Progress

by Samuel Hux (September 2017)

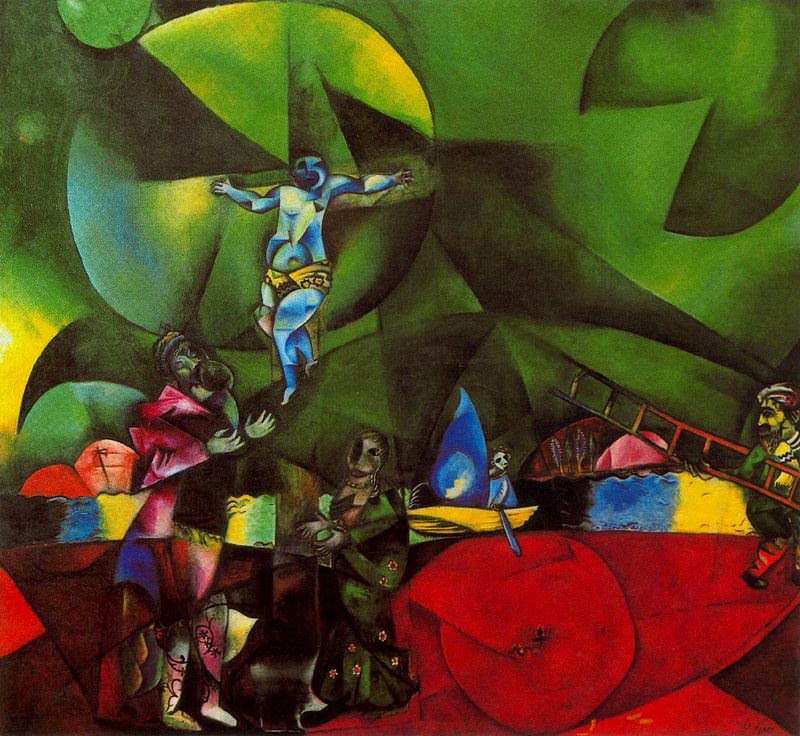

Calvary, Marc Chagall, 1912

“The victim is guilty.” That’s a common judgment in this and the past century. It has much to do with psychoanalytic modes of thought, as in: “The oppressed have a way of ‘creating’ their oppressors; the sadist often responds to an implicit invitation from the masochist.” But it has much to do with popular modes of non-thought as well, as in: “It’s her fault; she really wanted to be raped.” And I think that ought to make us reconsider our received wisdom. The rapist will rape; he’s the guilty party. The sadist doesn’t need a masochist; he’s an independent actor in his moody solipsism; he’s the guilty party.

At a rather more sociological level there’s another common judgement in our time: “The victims are guilty . . . of being a problem.” Were they not a problem they would not be victims. How so a problem? A good question. Who is and who has the problem? If we do not like you, are you the problem we have, or are we the problem you have? Somehow, the latter would seem an equally-just conclusion. But if we change the literal terms we use, you can seem clearly to be the problematic one; and history and language have allowed us to do just that. Consider the specific case I have in mind.

Change the rather aggressive word problem to the somewhat more pensive question. Instead of saying “You are a problem” we say “You raise a question by your being which we must cope with (probably at your expense).” Both may mean the same thing ultimately but the latter (minus the under breath parenthesis) sounds ever-so-much-more thoughtful. German has given us the phrase die Judenfrage, “the Jewish Question.” The clear implication: “The Jews raise a question by their being which we must cope with.” But, by the logic suggested above, who raises the question, who has, who is, the problem? Why can’t we call the whole familiar thing “the Gentile question”? And if you’ll indulge a moment’s linguistic play . . .

There is no native word in German for Gentile; the state of being Gentile is just a given. Instead, there is the word Nichtjude, “not a Jew.” So if you coin the word Nichtjudenfrage, and translate loosely and creatively, you come up with the truth: Not a Jewish question. Nonetheless, it’s been a problem for the Jews, because an astounding number of Gentiles do and have had a problem.

That problem, in its passive and aggressive forms, is the occasion for this article.

In brief: We live in an age of brutality in which a particularly valuable idea of culture gets the shortest of shrifts. The western world, in general, has no sense of the necessary union of the intellectual and the ethical: no sense that culture and morality are not just-quite-naturally sunderable faculties or dispositions. The specialist imperatives of our age reveal themselves in the limits of profession, of course; but they reveal themselves in the dissociations of judgment as well. Chicken or egg? It hardly matters. By our standards we might judge a murderer to be “cultivated” if he’s well-read enough. Or if he listens to Lieder. (That allusion ought not to suggest that the Nazis exhaust that dissociation of faculties: they were, rather, the deadly epitome of a trend. Consider for example Hitler’s architect, munitions minister and, in effect, slave labor czar Albert Speer, who H.R. Trevor-Roper said was culturally and intellectually “in Hitler’s court” utterly “alone,” and whom Trevor-Roper judged to be, and for that ironic reason, “the real criminal of Nazi Germany.”) And the absence of that idea of culture as a union of intellectual-aesthetic apprehension and ethical behavior accounts in no small way for this age of brutality.

But absence is perhaps too strong a word. For that unitary idea of culture is what, I contend, characterizes the Jewish tradition—quite beyond a religious creed and/or an historical experience. Jewishness—clearly I am speaking “in the ideal”—is, I propose, the marvelous exception to the ethos of sundered faculties. And, unfortunately, that’s a problem. A people who represented what is best in our civilized traditions became the victim of those who took the dissociating tendencies of the age to fulfillment. There’s a dreadful logic to the events of the 20th century.

But that logic did not spring ex nihilo. National Socialism as it truly was—distinct from the various left-wing nationalisms and national syndicalisms and anti-Semitic populisms of which its earliest supporters and critics thought it the historical epitome—did spring from Hitler’s mind, and that birth is a sort of “out-of-nothing.” But once born it needed nurture—and a warm atmosphere was ready. Whence and how that atmosphere?

I don’t expect any hesitation to accept my harsh words for Nazidom in this rather lengthy essay, for words cannot be harsh enough. But I expect some hesitation about my characterization of the dissociation of ethics and cultivation as “The Gentile Question.” If to the possible charge that I am dismissing an old “question” by loading a new one I have to answer: so be it. It’s also true that no one is suggesting neutralizing or getting rid of Gentiles, of which I am one. (Nor am I making some ethnic argument: individual Jews may be “Gentile” in this respect.) And even if one accepts that separation of ethics from cultivation as the nurturing atmosphere for the abominations of the age, I expect considerable hesitation about my speculations (and that’s what they are, no more . . . and no less) that the separation of cultural assumption and moral action is related in some more than incidental manner to the longest and greatest debate in Christianity (save perhaps the nature of Jesus and the Resurrection): the problem of St. Paul’s soteriology (doctrine of salvation).

Paul famously argued in Epistle to the Romans and elsewhere that salvation was not achieved through Good Works, that while Good Works pleased the Lord, salvation was not their reward, and that salvation was through Faith, and Faith alone. Which, read or twist it how you wish, has to suggest a relative devaluation of Good Works, of ethics that is.

I hasten to insist there is no attempt here to lay the Nazis at St. Paul’s feet. I have no such intention. (Never! Paul is in fact an intellectual hero of mine, which is another and here irrelevant story.) My intention is much more tortuous and inexact: to suggest that the relative devaluation of Good Works could well have been a first step in Christendom’s, or “Gentiledom’s” rather, cutting ethics loose from cultivation as a mere disposition—with consequences no one could have foreseen.

Now, I have a problem, which I’d do well to face up front. For I have here a considered surmise—that the abominations of the age were facilitated by a divorce of ethics and cultivation which was facilitated by the relative devaluation of Good Works in Pauline Christian theology—which I cannot prove by any empirical test. But in a sense the problem is a greater one for the insistent empiricist himself who would, by his skeptical disposition (often tyrannically skeptical), invalidate a great deal more intellectual discourse than he suspects. Something Erich Heller said in The Disinherited Mind seems to the point.

It is impossible to destroy an analogy ‘empirically,’ however much ‘evidence’ is assembled for the campaign. All historical generalizations are the defeat of the empiricist; and there is no history without them. Apply the strict empiricist test to the concept of ‘nation,’ ‘class,’ ‘economic trend,’ or ‘tradition,’ and the concept dissolves into a host of unmanageable minutiae.

If I cannot prove my surmise to a skeptic’s satisfaction, I request a certain freedom from that debilitating “rigor” (so perceived) of the most confining reaches of academic scholarship (“Germanic” scholarship, one might say) in which every statement must be seconded by accumulations of previous scholarship judged sound and not dangerously speculative before one may with confidence advance to the next statement. Any such endeavor is doomed in any case in intellectual and cultural history. For while one may document that B picked up such and such an idea from A because he said he did, or may semi-document same because B, who is known to have read A, formulated such and such in such a suggestively similar or provocatively contradictory way, ideas are in fact not always passed on as ideas. As often as not, they travel as muted assumptions and fuzzy dispositions, and are thus much less subject to empiricist rigor. We are thrown back then into the world of Heller’s caveat—where I prefer to be anyway.

Which is another way to say this is, rather than a scholarly article, an “an essay”—which ideally presents not merely conclusions but exposes the actual processes of thought. If the heavy gunnery of Germanic scholarship is missing, the lonely gunner is visible throughout. No place to hide.

Furthermore, the essay tends toward what the French call haute vulgarisation. “High popularization” is directed not to the specialist scholar (although of course he or she is welcome) but to the serious, educated, general reader. And it’s directed in a specific way; that is, not as a demand for agreement, but as an invitation to somewhat relaxed discourse about significant matters: a conversation, as it were, of which the essay itself is only half.

So, now, onward to my half . . .

St. Paul’s elevation of Faith over Good Works has bred enormous theological difficulties.

For instance, to what degree was the relative devaluation of Works an inspired rhetorical strategy to free the followers from a too-legalistic adherence to Mosaic Law and all those Deuteronomic dos and don’ts of daily observance? To what degree was it a modest correction of the too-self-reliant and potentially prideful apparent good sense that you work your way into God’s good graces through being your brother’s keeper? Or: what are the odds we miss the point altogether by miscomprehending Faith in the first place?

Paul Tillich judged that we did. Tillich defined faith not as “belief” (as when one believes in spite of insufficient rational or historical evidence: “a leap”), but as “ultimate concern,” meaning both (1) a concern which is ultimate—“unconditional, independent of any conditions of character, desire, or circumstance . . . total: no part of ourselves or of our world is excluded from it; there is no ‘place’ to flee from it” (Systematic Theology, volume I)—and (2) a concern for the Ultimate, the Unconditional. Ultimate concern is not a process we can initiate. It “happens” when we are seized by the Ultimate and cannot help but respond with that “restlessness of the heart,” a “passion for the infinite” (Dynamics of Faith), already implanted there in us pre-seizure. (Which process/event corresponds roughly to “irresistible Grace.”) Faith as ultimate concern—not a cognitive leap—is experienced then as a restless desire for union felt to be reunion with that “to which one essentially belongs and from which one is existentially separated.” As such, the “concern of faith is identical with the desire of love: reunion with that to which one belongs and from which one is estranged.” Since “the immediate expression of love is action,” that means Works. Works are implied in Faith as ultimate concern. But how the Faith compelling love for the Ultimate necessarily translates into love compelling action toward neighbor—Works, ethics that is—is a problematic affair. But, for now, Faith as “belief in things without evidence” implies no “direct dependence of love and action on faith,” as Tillich argues, correctly it seems to me.

Now, the brilliance of Tillich’s theology reminds us of what we knew already. This is vintage Tillich and heroic labor. Faith as ultimate concern is more attractive and engaging and perhaps profounder than Faith as belief-in-spite-of. But it is not Paul. Paul’s Faith, belief, is Karl Barth’s: “the gift . . . in which men become free to hear the word of grace . . . in spite of all that contradicts it” (Dogmatics in Outline). The priorities of Pauline Christianity are sufficiently clear: Faith over Good Works.

Carl Jung, of Protestant background, once said that Catholicism was more stable than Protestantism in that it walked on two legs, Faith and Good Works, rather than hobbling on one, Faith. By and large, Catholicism has, through complex theological exercises, managed to build up the musculature of the second leg. And by and large Protestantism has, while preaching Paul with a vengeance, tended to ignore just as often its own preachings in favor of more compelling stuff more appealing to parishioners: Think good / Do good / Be good sounding from the pulpit in no way secondary to Keep the faith.

Now, if there’s no such phrase as by and small, let’s invent it. For in the by-and-small there was a radical tradition of urges to special spiritual condition removed from biblical ethical commands which lived on in a kind of too-literal “Pauline” imagination: the tradition of “antinomianism.” Antinomianism in a religious context is the belief that since the Elect receives faith and salvation through God’s free gift of grace and not through any personal moral effort (pure Paul), it follows first that the Mosaic Law has been superceded or rendered irrelevant, and second that the saved is free of mundane moral obligations, which is certainly a putting of Works in their place.

The first antinomian of the first disposition (a half-way antinomian so to say) was Paul himself. I’m convinced he surely had no wish to debunk the ethical even while arguing it did not win you salvation. Indeed, his ambivalence about Jewish law seems in part an odd suspicion that it aroused sin (as if sinful human nature had to be aroused): “I should not have known what it is to covet if the law had not said, ‘You shall not covet!” But, considering the fact that the Mosaic Law is nothing if not an ethics (one without which Christ’s teachings about earthly behavior are unimaginable), it’s ultimately a matter of tone; and Paul, in his revolutionary urgency, often becomes atonal: we are discharged from the law, dead to it, no longer its captives. So, some might be excused for listening to the Pauline dissonance more than the Pauline word and imagining an invitation to antinomianism of the second disposition: the saved are free to sin.

One of the early challengers of Christian orthodoxy was the 2nd-century theologian Marcion. Although there were rumors—probably spread by his enemies—that he was a seducer of virgins, Marcion was evidently a nice boy who didn’t go all the way. But he went pretty far. Marcionism would have rid Christianity not only of Mosaic Law but of all Jewish impurities, and would have cast out not only all gospels save a modified Luke, but the Old Testament in its entirety, as well. Mistake: well it was avoided.

The 16th-century German reformer Johannes Agricola proposed the extreme antinomian position as clearly as possible. “Art thou steeped in sin . . . ? [No matter.] If thou believest, thou art in salvation. All who follow Moses [the Mosaic Law] must go to the devil. To the gallows with Moses.” This in theological disputation with his two great Lutheran contemporaries, Martin Luther himself and Philipp Melanchthon.

In a good history of Christianity, from Marcion to Agricola and beyond, one finds antinomian curiosities—from 2nd-3rd-century Adamites on. And one finds this or that group or thinker charged with antinomianism, indicating its persistence as reality or threat. To New England Puritans, the followers of saintly Anne Hutchinson were “antinomians,” which couldn’t have meant much more than “anarchists.” Luther was often charged with it, even though he disputed with Agricola. Because of its emphasis on Good Works as a way to salvation, the Epistle of James was to Luther “an epistle of straw.” As for the Mosaic, “We do not wish to see or hear Moses . . . They wish to make Jews of us through Moses, but they shall not.” Which while not as circumspect in tone as Melanchthon’s words to the same effect—“It must be admitted that the Decalogue is abrogated”—is still not quite as maddened as Agricola’s fulminations. Which fulminations, “To the gallows with Moses,” become historically laden. I am not suggesting Luther was thoroughly antinomian, but I grasp the nature of the suspicion.

But this is quite heavy and there is a lighter side. When you examine the “sins” antinomian sects practiced, freed as they were of the law, they’re often comic. The habits of the Adamites were quite charming. Stripping things down to essentials, and having been born again, they preferred communal worship in their birthday suits. And should you forget formal -isms and -ites and look to some idiosyncratic contemporary manifestations: the chronicler of randyism, John Updike, has been called an antinomian. Note his novel A Month of Sundays, in which Episcopalian priest, lusty as a sailor, has a girl for every Sabbath. Pardon me if I don’t take this kind of “antinomianism” with proper seriousness.

Strong antinomianism, call it—not silliness, not nudity, not incontinence, but sadistic violation and even murder—tends not to be formalized in sect or group. The strong antinomian tends to be a freelancer. And when he is of a sect, it tends to be a sect of his own devising, like that of the saint of Jonestown. (Remember Jim Jones, 1978?) In any case, the antinomian is special, his spiritual status extraordinary; speak not to him of Works and laws which may be suitable for lesser types like us. Ethical behavior O.K. enough for the hoi polloi is not binding upon him: perish the crude thought.

Now, although these radical notions are not endorsed by formal Christian doctrine, for even formal antinomianism was a single- and simple-minded misreading of Paul (no matter how much Paul left himself open, as original thinkers often cannot help but do), it is only defensive question-begging to protest that it is outside the Christian tradition

For the sake of clarity, I repeat: The dramatic break with the Hebraic notion that Good Works were a precondition for salvation, was a giant step in a process of great moment, the dissociation of behavior from mental action, ethics from culture.

Now, I realize that Faith is not equatable with Culture the way that Ethical behavior associates with Good Works. Certainly not now, in a mostly profane age. But for the longest time in Western history there was no Culture which was not in some way an expression of Faith, both the Faith of the believer and the Faith which is believed in: fides qua creditur and fides quae creditur. I mean of course Giotto, Bach, Dante, the Summas, and the book of nature: art, music, literature, philosophy, history, and natural science. And, viewed another way, the Faith as an institution, the cultus with its modes and hierarchies, was a Culture in the broad and social sense. So the terms are not alien either; indeed, feed one another.

Now . . . what if, in the Pauline doctrine of Faith and Works, there had been a dynamics whereby Faith, of itself, compelled Good Works . . . theoretically at any rate? I am not so bookish as to believe that a theological theory, a reformulation of Paul, would in some directly causative way have necessitated in a person of Faith a need to Good Works, to social obligation toward one’s fellows. Nonetheless, we’re an enormously suggestible species, and if theory doesn’t work miracles in a causative way, ideas have consequences, as Richard Weaver used to say. That is, a theory which held that a necessary consequence of Faith was a compulsion to Good Works might have had a suggestive power subliminally and to the consciousness, just as, I judge, a theory that one is justified by Faith alone has had a suggestive power!

One of the paradoxes of Christian history is that one theology, Calvinism, which when viewed one way would seem to encourage social quietism, when viewed another seems to have compelled great social activism. One is justified by Faith alone and not by Good Works. The salvific Faith is a concomitant of the free and unearned gift of Grace extended by God to his Elect. While God, “in his secret counsel,” elects his saints and damns whom he rejects to eternal fire, “his election is but half displayed till we come to particular individuals, to whom God not only offers salvation, but assigns it in such a manner, that the certainty of the effect is liable to no suspense or doubt,” as John Calvin put it in his Institutes of the Christian Religion, most likely making claims for himself. For the rest, however, whether one is Elect or Damned is a great mystery. But if one assumes, as he observes his station in society, that he is Elect, his fortunate circumstances being an outward sign of his inward state, then he might judge it acceptable to relax into quietism. And if one assumes, observing his unfortunate station, that he is not one of the Elect, he might resign himself to hopelessness and quietism: “What’s the point?” The view from one perspective.

Now, the view from the other: Since most Elect and Damned are subject to “suspense or doubt,” the best way to convince themselves and others that they have been chosen may be with great shows of piety and action. The sheer uncertainty implicit in Calvinism amounts to the power of suggestibility. And note that it isn’t Faith which thus compels Works: it’s the attempt to show that you have it—a different dynamics. This suggestibility-in-uncertainty strikes me as a good explanation of the strenuous ethical impulses in the very Calvinism which teaches that Works can gain you nothing in the way of salvation.

The suggestibility in Luther’s theology is quite a different thing. In The Bondage of the Will (De servo arbitrio, 1525), for instance, which he said was the best exposition of his thought (which isn’t saying much, Luther being philosophically the sloppiest of the major theologians), he ranted against free will (“the permanent bond-slave and servant of evil”). Enraged by Erasmus’ On Free Will (De libero arbitrio, 1524)—”such vile dirt,” Luther called it—in which the great humanist had defined free will as “the ability . . . whereby man can turn toward or turn away from that which leads unto eternal salvation,” Luther concluded that “though I should grant that free will by its endeavors can advance in some direction, namely, unto good works, or unto the righteousness of the civil or moral law, it does yet not advance toward God’s righteousness, nor does God in any respect allow its devoted efforts to be worthy unto gaining His righteousness; for He says that His righteousness stands without [meaning outside] the law.” While “can advance in some direction” might seem an opening, it leads nowhere. Especially if one considers a quite remarkable passage I quote at length to suggest a quite different order of suggestibility from what you find in Calvin. (And one has to wonder if Paul would not be stunned by what follows.)

As for myself, I frankly confess, that I should not want free will to be given me even if it could be, nor anything else be left in my own hands to enable me to strive after my salvation. And that, not merely, because in the face of so many dangers, adversities and onslaughts of devils, I could not stand my ground and hold fast my free will—for one devil is stronger than all men, and on these terms no man could be saved—but because, even though there were no dangers, adversities or devils, I should still be forced to labor with no guarantee of success and to beat the air only. If I lived and worked to all eternity, my conscience would never reach comfortable certainty as to how much it must do to satisfy God. Whatever work it had done, there would still remain a scrupling as to whether or not it pleased God, or whether He required something more. The experience of all who seek righteousness by works proves that. I learned it by bitter experience over a period of many years. But now that God has put my salvation out of the control of my own will and put it under the control of His, and has promised to save me, not according to my effort or running, but . . . according to His own grace and mercy, I rest fully assured that He is faithful and will not lie to me, and that moreover He is great and powerful, so that no devils and no adversities can destroy Him or pluck me out of His hand . . . I am certain that I please God, not by the merit of my works, but by reason of His merciful favor promised to me. So that if I work, too little or too badly, He does not impute it to me, but, like a father, pardons me and makes me better. This is the glorying which all saints have in their God!

While this may be great comfort to those whose Election “is liable to no suspense or doubt,” it is both to the saints and to the suspenseful and doubtful both an invitation to and justification of quietism, whether intended or not. Free will (and, logically, its attendant responsibility), were it even possible, would be a bad thing to have! And the suggestibility in Lutheran theology, so unlike that in Calvinism, has had its effect. Erich Kahler, in The Germans, held Luther accountable in great part for the submissiveness to authority (“utter freedom in the realm of the mind and ‘spirit,’ utter subjection in the realm of the body and the body politic”) that formed the German character and shaped the course of German history.

The suggestibility in Calvinist theory goes a long way toward accounting for the affinity for the Old Testament Jews, so unlike Luther’s distaste (“We do not wish to see or hear Moses.”). It’s difficult to imagine a great Lutheran movement for political and social action inspired by the Exodus story, as Calvinist movements were so inspired. It makes sense that in Michael Walzer’s brilliant Exodus and Revolution there are several comparative allusions to Calvin and Calvinists, and none to Luther.

The Confessing Church (Bekennende Kirche) in the 1930s was one of the few instances of courageous Christian collective action against Nazidom in Germany, and some of its deserved reputation has accrued to German Lutheranism, since Martin Niemoeller (who survived Dachau) and Dietrich Bonhoeffer (who was executed at Flossenburg) were members. But as the Protestant church historian Kenneth Scott Latourette pointed out (Christianity in a Revolutionary Age, volume IV), the Confessing Church was primarily the creation of and was sustained by churchmen of the Reformed tradition (Calvinist) and “Few of the oldline Lutherans went into active resistance, and many of them were critical of fellow Lutherans who coöperated with” the Confessing movement, and some chose to cooperate with committees from the semi-pagan, “German-Christian” Church, the Nazi Reichskirche.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology (before and in prison) can be read, and should be, as a heroic attempt to reverse the peculiar suggestibility of Luther’s thought, even while he argued that Luther didn’t really mean what he apparently meant. (He did.) Bonhoeffer’s definition in The Cost of Discipleship (Nachfolge) of “cheap grace” as “grace sold on the market like cheapjacks’ wares . . . grace as a doctrine, a principle, a system . . . forgiveness of sins proclaimed as a general truth” can be read in retrospect as an unintended comment on that lengthy passage I have quoted from Luther. Cheap grace as a safety net. And the craggy argument developed in a remarkable series of letters from prison to Eberhard Bethge for a “religionless Christianity” in a “world come of age,” that God has withdrawn himself from the world so that we can no longer depend upon him and his grace, so that we must “recognize that we have to live in the world etsi deus non daretur” (“even if”—better understood in the sense of “as if”—“there were no God”)—this argument, beaten from the mind in historical crisis, birthplace of the radical “God is Dead” theology of some years ago, is no less than an attempt, it seems to me, to reverse the Pauline and Lutheran priorities of Faith and Good Works. And any attempt to return to the comforts of dependence on the grace of God and not on one’s own moral efforts is “a dream that reminds one of the song o wüsst’ ich doch den Weg zuriick, den weiten Weg ins Kinderland” (“Oh that I knew the way back, the long way to the land of childhood”).

Again, theoretically, there would be no problem if Faith implied Good Works. But, if I am moved by the act of a God so loving me in my helplessness as to sacrifice his Son, and if I am moved by the act of a God so loving me in my helplessness as to choose to send me Grace absolutely gratis, while that does imply that I should yield him a grateful love in return, at the very least, how does that dynamic imply that I must perform Works of love toward my neighbor and treat him or her with justice? It does imply that I should worship Him appropriately, and Works could then mean juristic, liturgical, ritualistic acts. It’s between Him and me. But appropriate worship doesn’t necessarily mean Love Thy Neighbor. Well, in a way it seems to. However, that command is given to the Faithful by Jesus the rabbi and Jewish prophet who hadn’t had the benefit of the Pauline epistles; and if Faith implied the compulsion to Good Works already, the urgent command wouldn’t have to be given: it would be but a gratuitous reminder of what one couldn’t help but do anyway, and nothing in the tone of the scriptural passages suggests it is gratuitous. Faith is not, that is, a kind of deterministic faculty causing Works.

Cut it how you will, Works remain relatively devalued. Faith and Works remain quite separate functions, neither one implied in the other. One is a trust that the divine isDynamics of Faith that “it is natural to deny any direct dependence of love and action [Works] on faith”—when, that is, Faith is defined as belief. But not when it is defined as ultimate concern.

I would remark in passing how “Jewish” Paul Tillich sometimes sounds to me. Perhaps it’s that weighty word concern, so much more demanding and uncomfortable than belief. Perhaps it’s the tenor of his thought rather than any specific theological instance. Perhaps, it’s that, in some way meant as a compliment to both, he reminds me of Martin Buber.

In Israel and the World Buber recalled that a Christian theologian once observed to him that “Jewish activism” seemed to know nothing of Grace. But it’s a different conception of Grace. “We are not less serious about grace because we are serious about the human power of deciding, and through decision the soul finds a way which will lead it to grace. Man is here given no complete power; rather, what is stressed is the ordered perspective of human action, an action which we may not limit in advance. It must experience limitation as well as grace in the very process of acting.” Man was not created morally helpless, totally dependent upon free and unearned gifts; he attains Grace in the stumbling process of action. “The great question . . . is this: How can we act? Is our action valid in the sight of God, or is its very foundation broken and unwarranted? The question is answered as far as Judaism is concerned by our being serious about the conception that man has been appointed to the world as an originator of events, as a real partner in the real dialogue with God,” (italics mine).

An “originator of events”—shades of Bonhoeffer!—not a helpless victim revived only by Gracious handouts. “This answer implies a refusal to have anything to do with all separate ethics, any concept of ethics as a separate sphere of life, a form of ethics which is all too familiar in the spiritual history of the West,” (italics mine in this near perfect definition of the Gentile Problem!).

I am convinced that I am right in this long disquisition—even if the readerly half of the conversation I invited upon beginning might be skeptical. But my task is tougher than casual reservation can be. To assign linear historical causes and effects so resoundingly convincing as to rule out any possible reservations would require no less than a history of every thought and every action of every Gentile over two millennia. To trace synaptic relations, so to speak, between religious institutions and theologies on the one hand and secular institutions and mores on the other would require a sociology I am neither capable of nor inclined to seek. So I leave the various analogies to persuade as they will or not.

No, that’s not quite what I’ll do. Rather, I’ll claim my rights, so to speak. I’ll expand that quotation of Erich Heller (The Disinherited Mind) which I offered much earlier.

It is impossible to destroy an analogy ‘empirically,’ however much ‘evidence’ is assembled for the campaign. All historical generalizations are the defeat of the empiricist; and there is no history without them. Apply the strict empiricist test to the concept of ‘nation,’ ‘class,’ ‘economic trend,’ or ‘tradition,’ and the concept dissolves into a host of unmanageable minutiae.

And, Heller continues,

In every single case the question is merely how profound and subtle a generalization is, or how much of the generalizing manoeuvre passes unnoticed; and it has every chance of not being recognized for what it is, if it is in keeping with the silent agreements and prejudices, the prevalent generalizing mood of society.

While I do not think my analogies are in keeping with the silent agreements and so will not go unnoticed, I do, of course, think they pass the test of subtlety and profundity. But in any case . . .

Given the enormously persuasive power of suggestion inhering in doctrine, given the fact that no national or universal body of indicatives and imperatives in Western history has had anything remotely approaching the persuasive power and influence of Christianity, given the tempting analogy-at-least between the devaluation of Good Works as a path to Salvation and “any conception of ethics as a separate sphere of life” (Buber), if there were no conceivable connection between The Gentile Problem on the one hand and Paul’s fateful utterances on the other, you’d have a miracle.

This is not to assign a sort of “collective guilt” to Christian formulations and to Christians. (Nor is this a kind of Christian confession, it is rather in the spirit of a hard look.) Discussing collective guilt (and one knows the instance he has in mind) Tillich in Systematic Theology (volume II) argues that the “individual is not guilty of the crimes performed by members of his group if he himself did not commit them. The citizens of a city are not guilty of the crimes committed in their city . . .” But, nonetheless, “they are guilty as participants in the destiny of man as a whole and in the destiny of their city in particular; for their acts in which freedom was united with destiny have contributed to the destiny in which they participate. They are guilty, not of committing the crimes of which their group is accused, but of contributing to the destiny in which these crimes happened.” As with men, so with formulations.

I cut that quotation just before Tillich begins to descend, quite atypically, into banality: “even the victims.” Or perhaps that notion is saved from banality by brutal irony. Those who did not contribute to the “city’s” destiny did: their idea of culture as an integration of intellect and ethics was just too offensive to those who would sever the faculties. As I said at the beginning of this article, there’s a dreadful logic to the events of the twentieth century.

In any case, the Gentile Problem or Question appears in pure form only among those claiming to be cultivated in the first place. I don’t intend discussing mere criminality. Cagney’s “Public Enemy Number One” is not the subject here. A Shakespeare-quoting rapist could be. An Albert Speer needs to be explained. A drunken, depraved, culturally illiterate lout like Oskar Dirlewanger, commandant of the XXXVI Waffen-Grenadierdivision der SS, doesn’t have to be: he was offensive even to Heinrich Himmler, and would have been what he was had the maidenliest star in the firmament twinkled on his bastardizing—as Edmund more or less confessed in Lear. But the modes of the “cultivated”—from Speer down—could be imitated by the Adolf Eichmanns who in normal times would have sold insurance and lived respectable if culturally uninspired lives. That the “Popes of the Third Reich,” as Eichmann conceived them, his cultural betters, could divorce ethics from professed culture, allowed him all the more easily to divorce ethics from ordinary respectability. So, one might say, that although he didn’t have the Gentile Problem he lived it anyway.

Now, clearly I would not employ the phrases I do—The Gentile Problem, The Gentile Question—and might simply employ “The Ethical-Cultural Divorce” or somesuch, did not The Jewish Problem, The Jewish Question, die Judenfrage, already—as historically catastrophic phrases—exist. So there is a kind of ironic retributive justice in my diction.

And it’s clear that the most dramatic and terrifying manifestations in history of The Gentile Problem have been various inquisitions intended to resolve, even unto the Final Solution, die Judenfrage so assumed. But there’s a certain symmetry quite beyond ironic linguistic analogues implied in the use of Problem and Question. That is, there is no real “Jewish Problem” because in the classical religious doctrines of Judaism and in the reigning secular cultural inclinations of the Jewish tradition there is no endorsed separation of ethical behavior from cultural responsibility. There is no question in Judaism of whether or not a rapist can really hear, grasp, comprehend what the cantor sings: he’s deaf to it.

________________________________

Samuel Hux is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at York College of the City University of New York. He has published in Dissent, The New Republic, Saturday Review, Moment, Antioch Review, Commonweal, New Oxford Review, Midstream, Commentary, Modern Age, Worldview, The New Criterion and many others.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting articles, please click here.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by Samuel Hux, please click here.