The Golden Age of Academe

by Ralph Berry (June 2022)

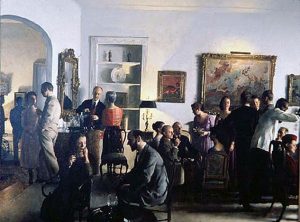

Cocktail Party, John Koch, 1956

Nobody ever tells you that the time you are living through is the golden age. But it happened for academe, through the 1960s. What a fortunate era for academics peaked in les evenements de mai, 1968! Higher education had surfeited on a decade of State-fed enrichment, following the Sputnik sensation of 1957. The shock-waves travelled round the West, with a couple of immediate conclusions. First, Russian, the language of the future, was to be advanced. University departments of Russian were set up, so that teachers of Russian could fill language departments in schools. Second, higher education was to be hugely expanded. Since no plausible distinction could be made between arts and sciences, all shared in the expansion. The party, a grand Western phenomenon, was on. A golden age dawned.

Nowhere was the party livelier than in the States. I saw something of this at the ending of the great decade. The best viewing was at the annual MLA (Modern Languages Association) held always a few days after Christmas. The MLA is a combined job and publishing fair, a huge event where academics pursue their careers and other intrigues. As I passed by the publishers’ booths, I was often stopped and asked: ‘Do you have a book on your stocks?’ ‘Well, as a matter of fact, I do.’ ‘Oh, good. Here’s my card. Would you like to come to our party tonight?’ And I would say, ‘I’ll try. But I’ve promised to go to the Oxford at 7, and the Norton is at 8. But I’ll look in if I can.’ These Trimalchio-like feasts were not to be slighted. In between came smaller departmental parties, usually coming with jeroboams of the hard stuff. Americans don’t do sherry.

It really was like that. And campus life reflected the glories of the era. A young ABD (his dissertation All But Finished) would, at the great universities, receive job offers in the mail without even applying. Largesse was spread thickly over a department. I remember the Growth Grants. These were made, by a munificent State, Massachusetts, to all faculty members who would file a grant application for a project that would advance their career development. It went like this, crudely: suppose your career would be advanced by a greater knowledge of the Italian Renaissance. You applied to spend some time in the summer in Florence and Rome, looking over the Italian Renaissance on the ground, having crossed the Atlantic on the Leoncavallo or Michelangelo. The grant was for a fixed $1500, and the Chairman would sign off the application at once. Problem: the Associate Chairman came around urging the faculty to apply for the Growth Grant. Apparently the Department was underachieving its quota. People wanted to play golf, or work on their next book, or simply relax after a stressed-out session. Taking up a free $1500 was beyond their horizon.

It was Paradise, and in those palmy days not at all difficult to enter. One

friend, just out of Yale, told me that he was getting unsolicited offers from Nebraska (‘I’m sure you’d like it here’). Another friend was finishing his PhD on Arthur Symons, a lesser star of the 1890s. Like other aspirants, he planted his flag on a patch of terra incognita and claimed it for his own. Applying before the MLA convention, he secured interviews with six chairmen and got tenure-track offers from three. The details have stayed with me. The offers (tenure track) came from Little Rock University, the College of William and Mary, and the University of North Carolina. My friend chose North Carolina, as the school with the best reputation. He went on to thrive. With him came a huge invasion of American graduate schools in the mid-‘60s as a way of escaping the Vietnam draft. One could readily get ‘graduate exemption’ and sit out the war: influx matched expansion. More students meant more Assistant Professors. Tenure itself was easily granted, for the large intake of Assistant Professors meant that they flooded the Personnel Committees. When the vital decision was to be made, two concerned members of the committee would take each other out to the corridor, swear eternal allegiance to each other, and then come back to vote the right way. The ambitiosi always got a majority verdict. Those were good days.

And then came les evenements de mai, 1968, a Western not just French event. It was a clap of thunder. The downpour came 18 months later for the academic world, and became visible in the MLA at Denver, Colorado. The sinister Denver ’69 falls on academic ears like the Field of Blackbirds on Serbs. Where there had been 4 jobs for three applicants, there were now three for four. Legislatures, prompted by resentful electors, had cut back on their university appropriations. Why should voters throw away their money on ungrateful students, and, worse, faculty that put them up to it? The fat years were over, and the beneficiaries of Growth Grants went into four consecutive years of salary freeze. There were other signs. One of the hot political topics of the day, pre-Denver, was a strong move to oppose anti-nepotism rules. These bore down on married couples—partners had not then been invented—who wished to work in the same institution, and indeed department. The authorities often disapproved and created rules to stop such combinations. After Denver, anti-nepotism was dropped, never to return. Couples were simply glad to have one of them on the payroll. As for publishing, books remained a necessity but not a profit (which they had been). Few academic books now go beyond the library order of 400 or so. Digital publishing has taken over. Academic book publishing has slumped into permanent invalidity.

The next dream is hard to discern. Russian, of course, was quietly retired long ago. The demand was never there. Will Chinese be the new Russian, with youth switching en masse to Mandarin? I think of De Gaulle’s line on Brazil: ‘Brazil is the country of the future, and always will be.’ The attractions of China are not about to displace those of the USA. As the current era recedes into history, it looks more and more like a Kondratiev wave, another academic boom that ends in severe transformation. I am glad to have seen the earlier golden age, a kind of expanded 1914 summer. To those who were there, the two disputed senses of a great inscription apply: Et in Arcadia ego.

The idyll of academe, the campus novel made flesh, is over. It may have started with Malcolm Bradbury’s Eating People is Wrong (1959), an account of a turbulent year in the English Department of Benedict Arnold University. Bradbury had done time at the University of Indiana and knew his stuff, but his book had mixed reviews. It still laid the foundations for his masterpiece, The History Man (1975). In the great era, all academe thrilled to David Lodge’s Changing Places (1975), about a professorial exchange programme which turned out to include wives. He followed it with Small World, which has this resonant induction: ‘When April with its sweet showers has pierced the drought of March to the root … then, as the poet Geoffrey Chaucer observed many years ago, folk long to go on pilgrimages. Only, these days, professional people call them conferences.’ They still do. But no one writes with Lodge’s light and sophisticated touch any more. Academe has been absorbed into the real world.

We go back to Guercino’s painting of the skull in Arcadia, the archetypal golden age. Death was present there too.

Ralph Berry has spent his career in Canadian universities, ending with the University of Ottawa. After that, he took a Visiting Professorship in Kuwait University, followed by the University of Malaya. In recent years he has written for Chronicles magazine. His hinterland is Shakespeare, but not as a figure of Tudor history. Shakespeare’s works are a mirror to today’s issues and themes, through which we can better understand today’s politics.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast