The Luxor Baths: A Reminiscence

by Marc Epstein (June 2019)

On October 2, 1949, my father gave my Uncle Willie Katz, the designated family Kohen, five silver dollars to redeem me, his first-born and only son. This ancient Israelite redemption ceremony, the Pidyan Haben, took place in a second floor room reserved for parties, at 121 West 46th Street, in Manhattan. My parents had been married for 14 years before I was born, and the event was considered of such moment that they had Genadeen Kosher Caterers prepare the event.

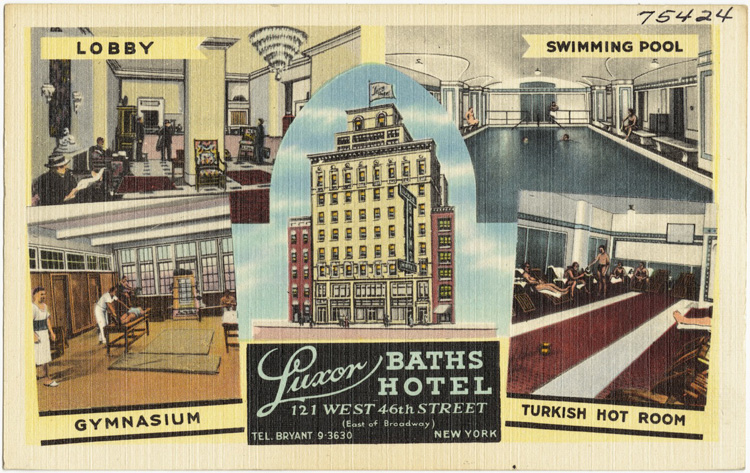

If there were a category in the Guinness Book of Records for unique destination ceremonies, this would rate an entry. That’s because 121 West 46th Street was the location of the Luxor Baths.

My father joined a partnership that included his brother-in-law Willie. It also included Julius Helfand, who was famous for his investigation of the fight racket and who would later become New York’s athletic commissioner and a Supreme Court judge. They signed a long-term lease on the building, which opened in 1925, at the height of the Twenties boom. Fred Epstein had been looking for a business opportunity, a way to make a living, an expression that was commonly used back then, after returning to the United States from Panama. The partnership was looking for a young man willing to run the day-to-day operation. My father fit the bill and he bought into the operation.

Read more in New English Review:

• Buddy Bolden, the Blues, and the Jews

• Let’s Eat Grandma: The Vicissitudes of Grammar

• No Friends but the Mountains: The Kurds

Uncle Joe sailed from New York to California on a tramp steamer and quickly realized, after traversing the Panama Canal, that nothing like the store he intended to establish at the homeport of the Pacific Fleet existed in Panama. It was a very shrewd decision.

When my father came down, he learned the business from Joe and set up shop in Colon. In addition, he operated stores on the bases located on the Atlantic side of the Canal while Uncle Joe took care of the bases on the Pacific side.

While the Pacific side of the family remained in Panama, and still resides there, my parents returned to New York, where my father embarked on his third career. He never reflected on his career changes. It was simply what one had to do based on circumstances to get on with life. He saw, adjusted, and went about his business.

The Luxor Baths was a Roaring 20s extravaganza that helped set that age apart. The building was nine stories above ground and two stories below. It was for men only, and with the exception of the two club floors, gym, and handball courts, which were closed on Sunday, operated 24/7, 365 days a year

It was located in the heart of the theater district. The first president of the Luxor was David Podolsky, an ardent Zionist, and one of the founders of Chovevei Zion.

The clientele, or habitués as they are called in a September 1963 two-page photograph (L) taken by famous Time-Life photographer Arthur Schatz, which appeared in Esquire, and in a 1964 Newsweek article entitled “The Oak Leaf Lunch,” were a decidedly democratically mixed bunch.

As Mel Brooks in his 2,000-year-Old Man incarnation would say, it comprised “the great and the near great.” And, I’d include the ordinary workingman from almost every trade and profession in New York City. But what set the Luxor apart for all the habitués, regardless of their wealth, power, celebrity, or ordinariness, was their desire to be lost not found.

The main entrance looked like a typical hotel lobby except for the wall of Mosler safety deposit boxes behind the check-in desk and the heat that you could feel emanating from the bath floor below. After you walked through the entrance vestibule there was a cigar and cigarette stand in the corner. It was a curved glass and wood showcase that was common in hotel lobbies. Sam sold playing cards, toiletries, candy, and gum, Sen-Sen the items that were requisite for your venture into the baths.

Upon checking in you would place your wallet and other valuables into an empty safety deposit box. The clerk would place the box in an empty vault, lock it, and hand you the key that was fixed on an elastic band. Whenever a customer availed himself of a service, his key number would be recorded on a chit and sent to the front desk to be added to the bill. The elevator operator would hand you a rolled-up dressing gown, towel, and canvas slippers.

The second floor, where I had my Pidyan Haben, contained the offices of Doc Milkstein. Dr. Milkstein was a physiotherapist, as they were called back then, who had hands of gold. He saw patients who never went to the baths, and whenever I found myself with a pulled back muscle or stiff neck, I didn’t have to be told to get on the subway and see Doc Milkstein. It would be decades later that I’d discover that I had a spinal condition that predisposed me to these periodic dislocations. Then, I simply did whatever I had to do to get on with things, much like my father.

General admission entitled you to a locker and a bed on the dormitory floors. There were hotel rooms on the 6th, 7th, and 8th floors. They were Spartan-functional, a place to sleep after spending your time and money on the bath floor.

Club members had the third floor for themselves. They had their own massage room, card room, TV room, and tanning room. They could keep their gym equipment with the floor attendants who saw to it that their gym clothes were laundered and their shoes were shined. I would spend hours watching and listening to Bill, who was in charge of the third-floor locker room and equipment, shine shoes, hand members their gym equipment, and relive stories of his earlier career as a Pullman sleeping car porter on the New York Central.

The gym was on the 4th floor. In addition to the weights, punching bags, and exercise mats, there was Ping-Pong room and golf driving cages. The handball and paddleball courts were on the 9th floor. During the warm months you could sun yourself on the 9th floor sun deck too. Besides the chaise lounges, you’d see bunches of oak leaves curing for the Russian rubbers to use.

The Luxor employed about one hundred men and women. They were comprised of all races and ethnicities with no particular tilt in any direction. The Hispanics were mostly Puerto Rican back then, and my father’s Spanish, picked up in Panama, served him well. We used to have a good time making fun of his linguistic skills when Joe, his all-around maintenance man, was around. Joe was from Spain and spoke Castilian. He could mend or make just about anything. My mother would jokingly ask Joe if he could understand my father.

It’s my prejudice, but I believe my father was a good man to work for. The staff didn’t turn over. I remember employees, usually the ones at the low end of the pay scale, coming to my father regularly for advances on their next week’s salary.

Barbara and Peggy did all the bookkeeping and secretarial work. All of them came to my Bar Mitzvah with their husbands, including Moishe, who ran the Russian Room, and his wife. There was a Luxor staff table at the celebration.

The Baths

The heart of the operation was the bath floor located one floor below the lobby. There were three categories of habitués: general admission, private hotel room, and club members.

When I first ventured onto the bath floor, my father always escorted me. I was just a very young boy. The only attraction for me was the swimming pool. It ran almost the entire length of the floor. The pool style was neo-Renaissance with Romanesque arched ceilings. Marble benches surrounded it with spittoons on the tile floor at the end of each bench. Water spouted from two lions’ heads at the far end of the pool. You entered the pool at the other end, down a tiled staircase with a brass railing. The staircase was wide enough that you could actually sit on the stairs.

I was told that I swam before I walked. My mother had to tie a rope around my waist to prevent me from running into the ocean in Long Beach. So the pool was the place for me. I didn’t begin to enter the hot rooms until I was at least ten years old.

The water was a beautiful shade of aqua and cold. It was deliberately kept at about 70 degrees for the customers who would cool off after their stints in the three hot rooms. They didn’t feel the chill at all. A couple of employees who had worked on the bath floor for decades told me that Johnny Weismuller swam laps in the pool. But the swimmer I remember the most was a WW II veteran who regularly swam his laps with one good arm and a shoulder. He had lost most of the other arm in the war. There were no bathing suits.

When the elevator door opened, the pine steam room was directly to the right of the elevator. The dry hot-room was to the left. The room for alcohol rubs and bankes (cupping) was to the right of the steam room. I thought bankes was some sort of ritual torture. The attendant would heat up glass cups with a small torch and place the cups on the customer’s back. When the cups were removed you would see bright red circles where the cups had been placed. My father assured me that it wasn’t painful and that the marks would vanish. It was designed to draw the bad blood to the surface. Bankes is back in vogue thanks to Michael Phelps, the great Olympian. I never worked up the courage to get the treatment.

The other side of the pool was a mirror image of the elevator entrance, but the rooms contained a different array of attractions. The Russian Room was probably the biggest attraction. You could avail yourself of a single or double Plaitzer administered by the expert Russian rubbers, get a Swedish massage, which was more of a deep muscle manipulation than the third floor massage, or a plain soap rub that was administered with the same kind of brush used on race horses. You could get hosed down with high-pressure hoses in the next room over, if that was your pleasure.

A bank of six tiled stall showers was located behind the water-spouting lions’ heads. There were lots of ways to get wet at the Luxor.

We never kept a scrapbook of pictures, but you can get a pretty good view of the floor in The Anderson Tapes, in The Rose (above), when Bette Midler breaks into the bath floor, and in the documentary film The Shvitz.

The first hot-room that I ventured into with regularity was the dry hot-room. You’d sit on a stone chair with wooden slats. An attendant would wrap your head in a barber’s towel that was kept in a bin filled with ice. He’d refill small cups of ice water periodically. My Uncle Abe liked to read pulp pocket books in the hot room, usually Westerns, that were always by his side. Those books were an escape from the spreadsheets and ledgers that filled his day. He was a CPA.

There’s a wonderful description of one of the habitués, George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff (below, R), in What Happened In Between: A Doctor’s Story, a biography by William J. Welch, who counted himself a Gurdjieff acolyte. The Wrights, Frank Lloyd and Olga, were followers too. In fact, Olga came to America as a dancer in Gurdjieff’s dance troop.

His abdominal girth was heroic and his presence in the Turkish bath, while not gargantuan, was at least the match of Rodin’s Balzac. He held court, when in New York, in the vast hot room of the Luxor baths on West Forty-sixth Street, an iced towel flipped around his bald head, his tiny feet splayed out under his vast belly above the expanse of which he poured himself tumblers of Perrier water, belching roundly, proclaiming with gutty satisfaction to no one in particular, “Bravo, Perrier!”

Regular visits to the bath were a ritual part of the festival of his life, and many of the men in the group around him became devotees of the hot room, the steam room, and even the Russian room, where the blinding heat, produced by splashing white hot rocks with cold water, was nearly more than could be borne, especially at the uppermost levels of the bleacher-like benches that lined the enclosure.

Other patrons must have wondered at the enigmatic, caramel-colored, fiercely moustached figure of Gurdjieff picking his way with feline grace from the hot room to the steam room to the Russian room, ultimately to lead his band of followers to the marble staircase going down into the neo-renaissance pool, which took up the central area of the baths. Only an “eedyot” would have the stupidity to plunge into the pool on emerging from the heat of the steam room or the sauna. (My son, Dick, received a dressing down for not restraining himself.)

Gurdjieff is barely a footnote today, but Peter Washington’s analysis in Madame Blavatsky’s Baboon places him alongside of Stravinsky and D.H. Lawrence, in his “…fascination with barbarism and primitivism which colours the politics of Fascism and works of art from Lawrence’s novels to Stravinsky’s early ballets.”

The pine steam-room was supposedly the place for secretive meetings. You could barely see the person sitting next to you on the marble benches that lined the room. There was a shower with a pull-chain near the entrance where you could cool off if it got too hot. It was the perfect vaporizer if you were suffering from a cold.

The moneymaking room for the Luxor was the Russian Room. The Dry Hot Room had large plate glass windows with the initials LB in the middle of a diamond shaped design. The Russian Room window was just plain multi-paned because whenever the Russian Rubber threw a bucket of water on the rocks to generate heat, the panes would bulge out from the pressure. They had to be replaced regularly.

The oven had to be rebuilt each summer. The large rocks, really small boulders that you saw in the oversized wall oven were the tips of a pyramid that extended one floor below.

They were carefully placed over a wooden arch structure that allowed a coke fed fire in the basement to heat the rocks up. There was a fireman on duty tending the boilers and the Russian Room fire around the clock. Once the oven was fired up it was fed throughout the year until the rocks wore out and could no longer hold heat.

Haley, a black contractor, did the work for $5,000 dollars (about $30-40,000 in today’s dollars) every summer. He hauled out the old rocks and replaced them with new ones that he took out of the Delaware River upstate. This never could have been accomplished in the current EPA Age. I wonder if he put the old used up boulders back?

You could sit on the benches on one side the Russian Room and cool yourself off with wooden buckets located under the water spigots on the benches. There were three levels, and it seemed that as you ascended the temperature rose about five degrees with each level.

The other side of the room had the same configuration, but it was used exclusively for the Plaitzer. In Yiddish your plaitzer is your back. The Plaitzer was a wash administered by the Russian Rubbers utilizing an oak leave brush. The leaves were collected and cured during the autumn and tied into brushes. They had the quality of not burning your skin when they were immersed in the hot soapy water and applied to your body.

I have a 7”x 5” photo of my father and Uncle Abe dressed as Russian Rubbers for a summer costume party in Long Beach. My father is wearing the old felt hat that the Rubbers used to keep your head from overheating and he’s holding an oak leaf brush—bezem (the Yiddish word for broom.) He had a sign from the baths that read Russia Soap Wash $1.00; With Plaitzer $1.50. Those were 1955 prices.

The costume party was thrown by the 22 Club, which was comprised of eleven couples who went to the same beach between Grand and Lindell Boulevards. They’d take Latin dance lessons together and go to the beach clubs on Saturday night for dinner and dancing. Back then beach clubs would feature headliners like Tito Puente, Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme, and Vic Damone in their nightclub.

The women drove 22 Club activities. They would hold an annual card party luncheon that would raise money for cerebral palsy. While the club was fixed at eleven couples, there was a widespread extended family in the neighborhood known as the “Walks” of Long Beach who participated. When I look at my Bar Mitzvah album, I notice the extended Long Beach group photograph. There are the members of the 22 Club along with our neighbors Grace and Igo Henig.

Ann and George Sandler were there too. They had five children, and that was considered to be an unusually large family, and they were all tall. Their three sons, Paul, Maurice, and Herman were all lifeguards on Grand and Lindell beach. Paul and Maurice became physicians. Herman, who was friends with my cousin Arthur, was one of the founding partners of Sandler O’Neill. I recall that Herman would come to the house wearing a boat-neck shirt with a pouch at the waist. He’d carry Gretchen his dachshund puppy in it. He had a very funny wry sense of humor. He perished on 9/11.

During the winter season, the Club would buy a block of theater tickets and hold benefits with the money going to charity. On a couple of occasions, we held a Chanukah party in the second-floor room where I had my Pidyan Haben. The men would get to go down to the baths while the women socialized upstairs. The women didn’t seem to miss us. We were going to come out clean as a whistle.

Once I overcame my fear of lying on the top level with a wet towel and old fedora hat to keep my head from burning, I came to realize why the Plaitzer had such a following and why it generated so much revenue.

The Plaitzer or, for an added fee, a double-Plaitzer, administered by two Russian Rubbers, combined exfoliation and exhilaration in one process. The Russian Rubbers would lather you on both sides of your body as they poured cold water on your head and on their own heads to keep cool.

You finished off the Plaitzer by climbing down and sitting on the lowest bench while they whisked the oak-leaf brush around your head and neck now that your head was uncovered. You washed the rest of the soap off at the shower that was in the corner right outside the door and went into the pool. I don’t think a drug induced high could replicate the feeling.

Moishe ran the Russian Room. Other Russian Rubbers included his son Sammy, Hendricks, Harry The Horse, and Henry. There was even a regular customer who everyone just called the Greek, who liked giving Plaitzers with the regular Russian Rubbers gratis.

Nikita Khrushchev’s son-in-law, Alexei Adzhubei, stopped in for what was supposed to be a good-will visit to the Russian Room. But things went awry when one of the Russian Rubbers knocked him off the table resulting in a black and blue head of Izvestia.

My father mentioned that FBI agents were always trailing someone into the Luxor and that they told him that spies could hide things in places you couldn’t imagine. I took that with a grain of salt, but years later I came across a Luxor Baths story from the 1930s that confirmed his account.

In August of 1934, Valentin Markin, the Soviet agent who recruited Whittaker Chambers, was found with a severe head wound, a fractured skull it seems, in the Luxor Baths. Markin died the next day after undergoing surgery.

When I turned eleven, I was deemed responsible enough to take the subway to the Luxor by myself. I’d get on the GG local at 63rd Drive in Rego Park and switch to the F train at Roosevelt Avenue. I’d get off at the 47-50 Rockefeller Center stop on 6th Avenue and walk around the corner.

The Luxor was right across the street from The High School of the Performing Arts. I was jealous of the dress and make-up of the student body. Back in the early 60s, NY public school students had to adhere to a strict dress code and code of behavior. That meant no jeans, no sneakers, and a tie every day. But at Performing Arts you were greeted with students in berets, all sorts of costumes, dance leotards, and the constant sound of instruments emanating from the building along with students hanging out on the street. The movie Fame captured what I was treated to whenever I journeyed to the baths.

It never occurred to me that the students at the “Fame” school would envy me if they had only known of the theater, television, and movie talent that flocked to the Luxor. Moss Hart, Tennessee Williams, Dore Schary, screenwriter president of MGM, Jack Warner, Barney Balaban, president of Paramount, are just the tip of the iceberg. This was the age before celebritydom became pornographic. Family, friends, or acquaintances never once suggested that the sign-in cards of the famous should be saved when they were no longer needed as a business record. This was a New York where a Tony Provenzano, Tennessee Williams, Bernard Gimble, Irving Kristol, Arnold Beichman, men who made their living in the wholesale food markets, diamond dealers, and just the average guy who plunked down $5.50 could mingle without pretense.

You can say that nudity is the great leveler, but there is more to it than that. The social breakdown and self-segregation articulated by Charles Murray and J.D. Vance had not yet taken hold. Today, the sociological dynamic I witnessed would be inconceivable. Even if someone with money to burn tried, he couldn’t recreate the habitat that existed in the Luxor Baths.

I was friendly with all the clerks. Chris lived in the Luxor and worked the night shift. I still have an autographed dollar bill that reads “To Chris, Best Wishes, Walter Winchell.” Three clerks usually wore a tiny rubberized apron in front of their waists to prevent the front of their pants from wearing out against the front desk. Sometimes Henry wore an eyeshade visor.

Lew Samuels, whom I always addressed as Samuels, as if we were English chums, would have me stand up against the wall next to the dumbwaiter that sent up the charges for massages, Plaitzers, and rubdowns. He’d draw a line to mark my height and then periodically keep track of my growth spurts. After he’d retired, Samuels returned part-time. The wall he used to measure me had been repainted, but he said he didn’t need to do it anymore since I was fully grown now. It was then, when I saw him again, that I realized how fond of him I was.

My father never taught me much about the business. I don’t think he ever envisioned that there was a future in it for me. But he did show me how to operate the switchboard and the elevator. The switchboard was the original piece of equipment from the 20s that required you to connect wires into numbered extension outlets when you wanted to connect an incoming call to a room. It resembled Judy Holliday’s device in The Bells Are Ringing. There was a speaker system on the bath floor that allowed you to page customers.

When I noticed a blackjack that was filled with sand and lead next to the cash drawer, I asked my father its purpose. He told me that the Saturday night crowd could be pretty rough and the clerks needed it for protection. Chris was assaulted during a robbery and my father was visibly upset. That ‘s why he encouraged cops to come to the Luxor free of charge. Whenever a policeman from the 16th precinct came to the baths, he’d tell them if any of his colleagues wanted to use the baths they were welcome, on the house. He told me that there was nothing like police walking in and out to discourage a robbery.

Jack Dempsey would go to the baths before he went off to work at Jack Dempsey’s Restaurant on 49th and Broadway. The clerks would address him as Mr. Dempsey, while patrons would call him Champ.

Marty Sampson, a pretty good middleweight in the 1930s—he was ranked 8th—lived in the Luxor. He’d always ask me “How’s your mother, how’s your sister?” I didn’t have a sister. He meant my first cousin Phyllis who he’d see when we came to the Luxor after seeing a show.

I gave up trying to correct him and would just say that she’s fine. Then Marty would ask me if anyone was giving me trouble. I’d say no. Then he’d let me know that if anyone was giving me trouble, I should let him know. He even gave me a couple of quick boxing lessons.

I noticed that when Marty would have his safety deposit box opened it would contain the biggest roll of cash I’d ever seen. When I asked my father about it he told me that it was “the vig.” I had no idea what that was until my father gave me a short and invaluable economics lesson.

The vig was short for vigorish, the interest rate charged by loan sharks. If you borrowed $1000 and didn’t repay it, you owed $1200 the next week. The week after that you’d owe over $1400. Marty was a collector in addition to managing boxers.

But my most memorable encounter with a boxer took place in the barbershop located around the elevator bank next to the restaurant. I was waiting to get a haircut and found my eyes riveted on a shriveled old man whose ear was just a single lump of flesh. I’d never seen an ear like that before.

But it wasn’t just the ear that made him memorable. Patsy was shaving a customer with a straight razor and I loved to watch that ritual. First, he’d put on the hot towel. That was followed by a pink cream coating for the first shave. Then he’d apply the final white shaving cream coat for the second shave. He would top it off with another hot towel and a face massage. I looked forward to the day when I could get that kind of treatment.

Patsy was sharpening his razor on the leather strop attached to the chair and when he let it go the metal hook on the end of the strop made a pinging sound against the porcelain chair. That’s when all hell broke loose. The old man jumped out of the chair and started boxing. He was throwing all sorts of combinations at the air in front of him. I was riveted by his remarkable combinations. Patsy quickly grabbed him and said Johnny, Johnny, sit down it’s all right, it’s all right.

Johnny was Johnny Dundee, one of the great featherweight and junior lightweight boxing champions, known as the “Scotch Wop,” who fought until 1932. When I told my father what had happened with the man with the strange ear in the barbershop, I got another lesson.

The great gossip columnists were regulars too, but Walter Winchell, Nick Kenny of the Daily Mirror, who wrote poetry and the song “Love Letters In The Sand,” and Ed Sullivan would never write blurbs about the telephone directory of big-time stars that frequented the Luxor. If you wanted your picture on the wall you went to Sardi’s. If you wanted your name in columns you went to the Copa, Latin Quarter, 21, or the Stork Club.

When I’d come face to face with Sid Caesar on the bath floor, I’d have that dumbstruck look of a seven-year-old recognizing an iconic visage from his television set. But my father rarely spoke of the celebrities who were devotees of the baths. Whenever friends or relatives would mention that they saw someone famous there my mother would say “Freddy, why didn’t you tell me.” My father would just shrug and say something like “What difference does it make?”

The only time I can recall my father introducing me to a celebrity was when Phil Silvers was in the restaurant with his entourage around him. They’d come up from the baths in their gowns and were eating in the restaurant when my father asked me if I wanted to meet Sgt. Bilko?

He brought me over, and Silvers had me sit down next to him. But within a couple of minutes of this close encounter his manager came over and announced that his wife had given birth to twin girls. Everyone shouted mazel tov and Silvers quickly departed.

Larry Goetz, a famous National League umpire from 1936 to 1957, was a regular who was nice enough to bring me autographed baseballs whose value I failed to perceive. The Brooklyn Dodgers in 1956 or ‘57 signed one of them. Buddy Parker, head coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers, gave my father an autographed football. Bobby Lane was the quarterback at the time. But we never valued or preserved those collectibles.

I always wanted to tell Jack Warden and Peter Falk how much I enjoyed watching them on TV and in the movies, but never summoned up the courage. I’d watch them check out and keep it at that. In homage to the baths, Warden inserted a line in Bullets Over Broadway, “We’ll meet tomorrow. We’ll discuss it. Luxor Baths, noon.” I’d listen to the wonderful voice of Ben Grauer, the NBC announcer and newsman as he gathered his belongings after his sojourn at the baths looking sharp the way a television personality should with his distinctive bowtie perfectly in place.

Joe DiMaggio and his brother Dom were regulars at the baths. There was an Italian restaurant across the street that they frequented too. My mother was waiting in the Luxor’s lobby. She might have taken me to a matinee, and DiMaggio was checking out. She said, “Joe, you mind if I ask you a personal question?” He replied, “Sure.” They both walked out of earshot and held a brief conversation. DiMaggio walked away smiling.

My father wanted to know what she asked him. She said she was curious if Marilyn Monroe looked as good in person as she did on screen. DiMaggio’s response was “She’s even more beautiful in person.” It was a much more innocent age.

My father wasn’t averse to good publicity but he was in no way tempted by the cult of celebrity. In 1955 Steve Allen did the Tonight Show live from the bath floor. There’s a blurb in Earl Wilson’s column, “The Midnight Earl,” announcing “Steve Allen will try to lose 10 pounds on his Monday show—from the Luxor Baths.”

My mother told me she got me up to watch it but I was too tired and went back to bed. The kinescopes of all those Tonight shows were destroyed. Nobody imagined they were historical documents. The only keepsakes were two blue terrycloth robes that they gave my parents and were used for many summers in our house in Long Beach.

From time to time after my parents had moved to Florida, Luxor tales would pop up. They were usually triggered when I’d be visiting them and we were watching TV. Henny Youngman was on a show, and my mother told me that she and my father went to Lindy’s for cheesecake after seeing a show on Broadway. While they were waiting to be seated, Henny Youngman’s voice rang out. “Everybody, look who’s here.” The entire restaurant turned their attention to Youngman who was seated with a bunch of other comics, waiting for his punch line. “It’s Epstein of the Luxor Baths. Epstein come sit over here.” My mother said, “if there was a hole available I would have crawled into it.” My father walked over and said hello, but didn’t join the group of performers because he wasn’t a performer.

Another time my father and I were watching a Hart To Hart rerun and Lionel Stander, who played Max in the show, was in a scene. That prompted my father to blurt out “a nasty SOB.” Stander, who famously compared the House Un-American Activities Committee to the Spanish Inquisition, was never a shrinking violet.

But my father’s aversion to Stander had nothing to do with his politics, the blacklist, or his acting. It was simply based on the time Stander got into an argument over his bill and took one of the adding machines that the clerks used to tally the bill and threw it on the floor. The machines were made by Burroughs and had 72 keys, a roll of adding paper, and a handle that you’d pull down after you made the entries. They cost about $400 in the 1960s, and that was real money. He told Stander he was going to have him locked up, and Stander’s manager quickly intervened and paid for the machine right on the spot.

At the Luxor you were only one degree of separation from power and wealth in all its forms, legitimate, and illegitimate. If you needed tickets to a show, concert, or a ballgame, they could always be had.

There was a retired policeman, Rocky—I never heard him referred to by his last name—who had his own locker on the club flood. His use of the baths was always on the cuff, as they used to say. Rocky had a second career as a treasurer in the Schubert Theater organization. In return, whenever my father needed tickets Rocky was the go-to guy. If the show was a big hit you paid for the tickets. But once the run of the show had tapered off or empty seats were available it would be off to a show at a moments notice. I took a girlfriend to see The Rothschilds with Hal Linden one Saturday night and was told to show up at the box office and just say Hymie sent me. I followed my instructions and two orchestra tickets were handed to me. It took years before I could bring myself to buy tickets to a show.

Another policeman, Detective O’Shea, was in charge of the plainclothes detail at Yankee Stadium. My father took me to see Jim Brown play against the Giants a couple of times and to a championship game against the Bears, only we didn’t have tickets. We just showed up where O’Shea was posted and he said, “Step this way.”

I never really understood these connections. They had an air of mystery about them. When I was applying to college my father introduced me to Buddy Ryan. Ryan wore a black cashmere coat with a velvet collar. There was a white carnation in the lapel and a Hamburg hat on his head.

I had no idea what he did for a living. My father said he worked out of the Democrat Club, probably Tammany Hall. He said, “Buddy, can you get my son a letter of recommendation?” Ryan looked at me and asked, “Where do you want to go kid, West Point?” When I told him the University of Buffalo, he just said get me the information.

I was accepted to Buffalo. Back in the 60s, it was the hot place to be. With Martin Meyerson running the show, it was touted as the Berkeley of the East, with an English department chock full of stars: Leslie Fiedler, John Barth, Lionel Abel, Robert Creeley, and Norman Holland.

When I had my first meeting with my guidance counselor to discuss my major and required course of study he looked at me and asked me if he could ask me a question. I said sure. He queried with, “Who the fuck do you know?”

To say that I was taken aback by the question and his use of the f-word would be an understatement. But then he showed me my folder. Buddy Ryan managed to get me a letter of recommendation from the Speaker of the House, John McCormack. In addition, my father asked Stanley Steingut, Speaker of the New York State Assembly, another Luxor regular, for a letter too. I’m usually never at a loss for words, but I simply couldn’t find the words to explain the dynamic of the Luxor Baths to a guidance counselor sitting in an office in Diefendorf Hall at SUNY Buffalo.

Nowadays we’d use the term “wired” to describe someone who had connections. But where Fred Epstein was concerned you’d never know it. My suits were never store bought. We always went to a manufacturer in the garment district to get it wholesale from a Luxor customer. Back then the saying was “I can get it for you wholesale.” Today it’s “I got it from Amazon.” Getting it wholesale was a much more enriching experience.

I recall seeing an invitation to a high school graduation and a graduation picture on the piano where the mail was usually placed. It included a personal thank you note to my father for having helped make it possible.

When I asked my father why he was invited, he simply told me it was a customer’s son. I had to pry the particulars out of him. “He was a kid who got into trouble.” “And . . ?“ I queried. “I asked another customer who’s a judge if he could help him out.”

Back then, getting into real trouble could mean joy riding without a license and getting into an accident. It could be enough to send you off to reform school. In any case it was a favor done that would have gone unremarked except for my nosiness.

Sidney Lumet’s The Anderson Tapes (above) had a few scenes filmed in the baths. It starred Sean Connery, Alan King, Martin Balsam, Dyan Cannon, and Christopher Walken. The premise of the film, presaging the Stovepiping of intelligence agencies prior to 9/11, follows various police agencies bugging a gang of conspirators led by John Anderson (Sean Connery) who are planning a heist on Labor Day. But whether it’s the FBI, the IRS, the NYPD, or a private detective, none of them have any cognizance of the plot unfolding before their eyes.

While Connery and King conspire in the hot rooms of the Luxor Baths, the attendant bringing ice water is wearing a bug. That of course is a fictional representation, but in the real world you could find a who’s who of the Mafia sweating their troubles away.

“Frank, I want to introduce you to my son Marc.” He shook my hand, asked me what grade I was in and how I was doing in school. He looked like a businessman in a gray suit. For all I knew he could have been a banker. Who knew?

Mario Puzo supposedly modeled the Godfather on Frank Costello. Don Corleone lived in Lido Beach, but Frank Costello didn’t. However, Tommy Lucchese (“Three Fingers Brown”) did. Lucchese was another regular at the Luxor and head of one the “Five Families” of New York.

Summers were the slow season for the Luxor, so my father took the opportunity to have his car tuned up at the Westholme Garage, on Park Avenue in Long Beach. We spent summers at our house at 5 December Walk, so my father dropped the car off and took the LIRR to work that day.

When he arrived home much earlier than my mother had expected, she asked him how he managed the commute home so quickly. He told her that a customer who lived in Lido Beach gave him a lift. When she asked who the customer was, he made the mistake of telling her it was Lucchese.

The Godfather was years away from publication, but The Untouchables, starring Robert Stack, was one of the top shows on TV. Al Capone’s exploits were now a weekly occurrence, and the Mafia and its methods had migrated into the popular culture. My mother gave it to my father with both barrels. She said don’t you ever get in a car with one of those guys again. They blow them up they shoot them. That was the last lift my father ever took from one of the regulars who resided in Lido Beach. Tommy Lucchese died in bed of natural causes, and it was pretty much the case for all the other syndicate regulars. It wasn’t the case with Jimmy Hoffa, but I wouldn’t count him as a regular since he didn’t live in New York, although he frequented the baths when he was in town.

Except for his five-day week during the summer, my father never really took a vacation. He was pretty much tethered to the “place.” There were the Jewish holidays and an occasional long weekend in the Catskills, but nothing much more than that unless it was medically induced.

After he had an operation to have the veins in his leg stripped, the surgeon ordered my parents to Florida for a week. When they returned home the get-well cards awaited. I held on to one of them for several years. It read, “Dear Fred, Get well soon! Your Pal, Joe ‘Socks’ Lanza.”

I thought Socks was the funniest nickname I’d ever heard. When I asked my father about it, he said he’s a nice customer who’s with the organization. By then I knew what that meant. Lanza controlled the Fulton Fish Market. When I asked why these guys liked him so much, my father told me it was because he never asked them for anything, with the exception of asking Miltie Holt if he could get me into the waiters’ union.

I had worked for a caterer as a busboy in high school. The pay was great, $20 for a Bar Mitzvah or wedding. Rego Park Jewish Center was only four blocks from home. The food, which was always in abundance, was another incentive for a growing boy.

I learned the waiters made about $120 an affair and that if you worked what they called a double header, you could make close to $500 working Saturday’s and Sunday’s! But you had to be in the union, and you didn’t get in by just applying.

Holt was president of Teamsters Local 805. He controlled the airports. I was told to go down to the union hiring hall and ask for someone whose name I don’t remember and then mention Milton Holt. When I got there I was greeted with a growl from someone at the entrance. “What are you doing here?” I said Mr. Holt said I should see Mr. X. The tone immediately changed to one of welcoming.

In the end I never pursued the job. I didn’t have a car, and you could be sent anywhere in Brooklyn and Queens. Instead, I opted for working in the Catskills. It was decidedly non-union but you still needed connections to land a job in the Raleigh Hotel.

My father’s interactions with law enforcement and the Mafia were never a topic of discussion at the dinner table. He told me that the FBI would always come trailing someone into the Luxor. He had no idea what deals were struck, information passed, or fates sealed in the baths.

He did have to testify in a Federal drug trial in Hartford as a material witness. The defendant, another regular, was on trial in one of the biggest drug busts at the time. The Luxor was one of his alibis and my father had to testify if he was in the baths when he claimed to be there. The records showed he wasn’t.

When my father walked off the witness stand, the defendant told him “don’t worry about it Fred. We’ll beat this on appeal.” He was right. His conviction was overturned.

We lived in an apartment house on 99th Street in Rego Park. It was an 18-story building with about four hundred apartments. Several tenants frequented the Luxor, but one of them was named in a Federal “fixing” probe that involved payoffs by Faberge to the Mafia to help settle a strike at one of their plants in New Jersey.

My father told the FBI that it’s a free country and he didn’t decide who lived in our building and who went to the Luxor. Then he told them to check with the Hartford office of the FBI about him. He never heard from them again. It was the J. Edgar Hoover Era, and for all I know they kept a file on Fred Epstein. Whenever I think that law enforcement might have seen my father at the epicenter of organized crime I laugh out loud.

Events at the Luxor weren’t always good for a retelling and a laugh.

Back in 1964 the phone rang about 2 am. I didn’t hear it, but before I went off to school my mother told me that my father had to go into the Luxor in the middle of the night. She thought a pipe had burst. The baths used lots of water and the plumbing was a critical and high maintenance proposition. When I got to school a classmate held up a copy of the Daily News. It wasn’t a plumbing problem at all. A customer had jumped out of a 7th story hotel room.

I looked up the story in the New York Times archive to refresh my memory. I had only read the description in the Daily News, and back then it was before the 24-hour “all news, all the time” Era that we are now subjected to. The story didn’t have “legs” which was just as well. My father didn’t discuss it at all.

Sydney Schanberg wrote the front-page story, “Theater Witness Is Killed in Plunge,” Those were the days when the New York Times did what it did best, report the news. In his close to a 1,000-word story, Schanberg painted a full picture of the deceased. William Weiss, 62 years old, lived in the Bronx and ran a ticket selling business “out of his hat . . . and did a yearly business as big as any of Broadway’s licensed brokers.” He was scheduled to appear before Frank Hogan, the Manhattan District Attorney, that morning.

The police said there was no foul play because his door was locked from the inside. The ticket scalping business was notoriously mobbed up, and perhaps he saw himself between the devil and the deep blue sea. Schanberg reported that two employees identified the body. When I read that I realized that my father was probably one of them and had said he just worked there to keep his name out the paper. He never mentioned anything about the aftermath.

There was a balding man with his hair brushed back who was something of a fixture in the lobby. He always wore a suit and pointy shoes that had a high shine to them. My father would chase him out of the lobby with regularity. When I finally got around to asking why he was sitting there and why my father always chased him out, he told me he was a bookie.

I didn’t know anything about gambling because my father didn’t gamble or drink. He was a terrific card player and had a weekly gin game that rotated from apartment to apartment after the game was banned from our Jewish Center by the rabbi. The stakes were never high, and the respective hostesses prepared fruit platters and snacks.

Then he explained what a bookie did for a living. He told me he didn’t want him using the phone booth in the lobby to conduct his business. The last thing he needed was to be singled out as a book-making establishment. Then the bookie disappeared for a few years.

When I saw him sitting in the lobby looking forlorn, I asked my father why he stopped chasing him out. He told me that the bookie had agreed to take the rap for a crime and serve three years in exchange for a $50,000 pay-off. But the real perp died before he got the money, so he wound up going to prison for nothing. It was a story straight out of Damon Runyon. My father said he felt sorry for him.

With time I began to differentiate clientele that varied depending on the day of the week. My childhood was confined to going to the Luxor with my father on Saturdays. But with time I saw the decided mood shifts that very much depended on the day of the week you were there.

On Fridays I would go to my grandmother’s for Shabbos dinner at 81 Morton Street. My Aunt Sylvia would drive there from Queens, along with my cousins Phyllis and Arthur. My father and Uncle Abe would meet us there after they finished work in Manhattan. My great-grandfather had purchased the brownstone in 1919, and his three children and their families had inhabited three of the floors until my grandmother, the last remaining child, became the landlady, renting the other floors to Satmar Hasidim who came to dominate the Williamsburg demographic after WW II.

My aunt, uncle, and cousins would head home when we had finished eating. My cousins were older and had their Friday night social life awaiting them. My mother wanted to spend time with her widowed mother, her neighbor Mrs. Greisman, and her daughter Birdie who’d come over for tea.

I had to keep the TV on low so the neighbors wouldn’t be offended on Shabbas, but since there was nothing to watch until the Twilight Zone, I’d keep it off and fidget. So would my father until he came up with the brainstorm of going back to the Luxor with me. Back then it only took fifteen minutes to drive from Williamsburg to 46th Street and get a spot in front of the Luxor. We would go the baths, he decided. My mother was happy with the arrangement. She knew that there was nothing that could top a Luxor cleanup for me, and she could keep her mother company without us lurking around.

Friday night was fight night at Madison Square Garden and was broadcast on channel 7. The restaurant was filled with cigar smoke as the customers ate, played cards, and watched the fights on the TV. There were groups of friends who would book rooms, play cards, bring a bottle of whiskey with them, and enjoy a boys’ night out. But if you were there Friday before sundown there’d be bearded orthodox men who worked in the diamond district on 47th street who regularly came to the Luxor for their erev Shabbos shvitz and bath.

Thursday was always the longest workday for my father. He didn’t get home until after 9:00 pm and would grab something to eat at the Luxor. He’d bring my mother a hot fudge Sundae from the candy store. I was much older before I learned why Thursday was his longest work day. Thursday was maid’s day off. The more affluent club members, the CEO’s, would meet their wives in Manhattan for dinner and perhaps a show on Thursday.

If you got the full treatment—exercise, hot rooms, Plaitzer, swimming pool, massage—and if you got a haircut and shave, you walked out of the Luxor Baths feeling like a million bucks. I suppose those multi-millionaires on Thursday night found themselves feeling more special.

When I turned fifteen my father would allow me to go to the Luxor with my friends Richie and Ronnie on a Sunday. He allowed me to get the keys and open up the club floor and gym unsupervised, which upon reflection indicated a great deal of trust that I’d never given much thought to before.

We had the gym, golf driving cages, and Ping-Pong room to ourselves. Then we’d go to the bath floor and finish up by getting a sunburn in the ultra-violet sunroom. It gave us that healthy look that our mothers loved to see.

On special occasions we would get tickets to a Ranger game. End balcony in the old Garden cost two dollars with your student ID card. After we had been to the gym and the baths we’d go to TAD’s around the corner on 47th Street. It wasn’t what you’d call high quality, but for a $1.19 you got a steak, baked potato, salad, and garlic bread. The Coke was extra.

Then it was over to the Garden to look at the professional hockey equipment at Gerry Cosby’s hockey store located in the Garden’s building until we were thrown out trying on the goalie’s pads while pretending we were playing hockey. After the game it was back to Rego Park and school the next day. The total cost, including carfare, came in under four dollars. We are still in touch and reminisce not so much about our vanished adolescence, but about this vanished New York.

When the Rangers made the Stanley Cup playoffs for the first time in my lifetime, we were lucky enough to have bought regular-season tickets that would entitle us to purchase tickets to the Stanley Cup series. We went to the Luxor and slept in one of the rooms until about 2 am and then got on line with bedspreads wrapped around us until they started selling tickets. The Rangers were dispatched in four straight games by Montreal.

Although my Panamanian cousins, Uncle Joe’s grandsons, Peter and Larry, who came up north to attend prep school in Massachusetts, made good use of Luxor whenever they ventured into New York for a short holiday, the Stanley Cup was one of the rare times I slept over. New Years’ Eve should have been another. The Luxor was right near Times Square, so my friends and I could’ve spent the night without having to take the subway back to Queens. But the Times Square New Year’s Eve spectacle was for tourists not us native New Yorkers. The thought of watching Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians at the Waldorf was also too much to bear. It was usually Chinese food that had the greatest appeal.

I had nothing personal against Guy Lombardo. He and his brother Carmen were regulars at the baths and were very nice. It’s just that the big band sound was beyond my ken. I recall going to see Showboat at the Jones Beach Amphitheatre, starring Andy Devine with tickets provided by Guy Lombardo, who often played there during the summer.

LUXOR BATHS CONCLUSION

When I became old enough to take the subway to the Luxor, I also began exploring the neighborhood. Back then 6th Avenue—nobody called it The Avenue of The Americas—had lots of attractions for a boy my age.

There was a used bookstore on 45th and 6th that had a sizeable comic book section. It always reeked of that musty book odor. The cashier sat behind an elevated checkout at the front of the store, where he was able to oversee all the customers. Nothing was kept in the kind of order you’d see at The Strand. It was like going through an attic.

When I walked towards 5th Avenue on 46th Street there was the classical record store that specialized in rare recordings. I never went inside because I couldn’t imagine what use I would have for 78-rpm records. The old heavy 78s in my grandmother’s house eventually wound up in the trash. But during my sojourn in Japan I became friends with Al Younghem. Al was a long-time resident of Tokyo who grew up in New York after fleeing Germany with his family in 1936. It turns out that he frequented that store and assembled a remarkable classical music collection that numbered in the thousands.

By that time I had developed a novice’s appreciation for classical music and had easy access to it in Buffalo, the not so well known home of the Budapest String Quartet, a fine philharmonic orchestra, and a wonderful concert hall designed by Eero Saarinen. Al would introduce me to different versions of the same composition and artists such as Josef Hofmann, who were unknown to me. He told me that the proprietor of that shop was named Meltzer, and whenever he visited his father in New York, he would drop by and purchase rare recordings and ask Meltzer if the de Reszke recording had come in. Meltzer would reply that it was still on back order. That was their running joke. Jean de Reszke was the great tenor of the late 19th century whose only record recording was either destroyed or didn’t exist. But there were rumors that there was still a copy out there, somewhere. And so the record store that I’d dare not venture into came to life. Al recently donated his entire collection to the Santa Barbara UC where it’s being digitized for posterity.

Technically the Luxor was between 6th and 7th Avenues. It was just around the spot where Broadway and 7th crossed each other in that distinct X pattern near Father Duffy’s statue. You’d never use 7th Avenue as the reference point. You’d always say between 6th and Broadway.

Read more in New English Review:

• Rock Around the Clock: Dance Mania of the Left

• Spinoza and Friends

• The Strains of a Nation

The Hotel Remington, which had a very narrow frontage, was next door. Of all the properties that were demolished on the block, that oddly configured property survived along with the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin. My father told me the Remington was a “cat house” and never explained the meaning. It was up to me to find out. It’s now a boutique hotel and the block has been named “Little Brazil.” I. Miller, a high-end woman’s shoe store, was on the corner of 46th and 7th. My mother always looked in the window but never bought anything there. She loved the quality but knew there was better value back in Rego Park. The Planter’s Peanut store next to the Palace. A man dressed up as Mr. Peanut stood outside welcoming people. You could get fresh roasted peanuts.

There were lots of camera souvenir stores that were plastered with “Going Out Of Business” signs because the rent was too high, or so they claimed. Those signs stayed up for years, a sure sign of a tourist trap. I would stand outside the Metropole Café on 48th Street and listen to the live jazz on the street. In the late 60s, they started to feature Go-Go girls in response to the culture shift.

There were the great movie houses that showed blockbusters like The Ten Commandments, Ben Hur, Spartacus, Around The World in Eighty Days, which would play in those movie houses exclusively for up to a year. There were no general admission seats, only reserved seating, just like you would buy for a Broadway play. They are all gone now, along with the Paramount, Astor, and Victoria.

When I got a bit older and my eating habits matured, I used to go into Toffenetti’s where you could order almost anything under the sun piled high on your plate 24 hours a day. Later on in the 60s, Nathan’s would open up in that location. While it’s hard to badmouth Nathan’s in its heyday, the loss of Toffenetti’s signaled the beginning of a downward spiral.

The “Twist” craze drew me to 47th street where the Peppermint Lounge was located. I was too young to enter a bar, but Joey Dee and The Starliters had the hit song “Peppermint Twist” and generated long lines that waited to get in and hear their one-hit song performed live.

With the advent of videotape live television disappeared with the exception of a few shows like Ed Sullivan. Most TV production moved to Hollywood. The break-up of the big studios had consequences too. The Roxy’s closing in 1960 foreshadowed the fate of Loew’s State, The Rivoli, and The Criterion movie houses. They no longer had exclusive blockbusters, and Radio City Music hall no longer featured a live show followed by a movie.

By the early 70s, the Times Square movie houses which were originally Broadway theaters going back to vaudeville days, were little more than flop houses showing old triple features. The theatre district had moved uptown years earlier. I rarely ventured over to 42nd street except to browse the newspaper store that carried papers from across the United States and the world.

But In 1971 my friend Ronnie got us jobs auditing the Neighborhood Youth Corps program for the New York Department of Labor. The program was established in the wake of the “long hot summer” urban riots of 1967. They were designed to give inner-city teenagers productive employment in a variety of programs. The audit was taken over by the state after a series of scandals that included Haryou-Act, the Harlem anti-poverty agency that was a by- product of LBJ’s Great Society program. It seems checks had been issued to people who didn’t exist.

Ronnie and I were a team that, along with about six other teams, randomly audited work sites throughout the city. We worked what were considered some of the worst neighborhoods in the city, but whatever bad there was to see didn’t stop us from making our rounds. We started early and we never encountered crime at that time of day. We were walkers in the city and in those few months probably saw more of parts of the city that were previously unknown to us than we had seen in a lifetime.

The work sites varied widely in both quality and legitimacy. Though we weren’t there to evaluate the quality of the programs we certainly took note of them. It was an eye-opener. We were there to make sure there were live people receiving the paychecks.

Ronnie was the navigator. He was getting his masters in operation research from Columbia, and his efficiency was astounding. We reported to our head office in Manhattan on Fridays to hand in our work and get our new assignment.

One Thursday we finished our week’s work early. We were in Harlem and the Upper West Side and headed over to the Luxor late in the afternoon. We went to the baths and then headed over to 42nd Street and saw the movie Shaft. Times Square had not yet turned into Midnight Cowboy territory in the daytime. But it wasn’t long before it would become just that.

My father began to alter his work habits. He no longer drove directly into Manhattan. The commute was no longer the quick 25-to 30-minute affair that it had been for decades. The parking fees began to become prohibitive too. So my father would drive to Long Island City and hop on the F train at Queens Plaza. It was only three quick stops and he said it shortened his commute. By then not only Times Square, but also some of our neighborhood movie theaters were showing hardcore pornography. The Deep Throat genre was now considered chic among elements of the educated middle class.

The cultural locomotive that began in the late 60s started coupling a series of cars to its engine that would help spell the end of the Luxor Baths. The baths and open homosexuality became a fixture in San Francisco. The Luxor hadn’t been a part of that evolution. But now, when you’d mention the Luxor Baths, people would ask my father if it was like Plato’s Retreat. There were gay customers, but everyone minded their own business.

When I worked at the Raleigh Hotel in the Catskills I served the show bands. The Raleigh was a “hot” hotel. They had star headliners in their nightclub and in addition a late show and a late-late show too. The late-late show was risqué and one of the big draws was an openly gay performer named Keri April. I’d serve the late breakfast to the guests because the musicians never made it to the regular breakfast and I had one less meal to serve than the waiters in the main dining room. The women would gush over Keri April’s outfits which were all high-styled custom-made extravaganzas in a somewhat more subdued Liberace genre. Back then there didn’t appear to be any clash of cultures.

I was already half way through college when the great 1968 school strike occurred, and living in Buffalo, I didn’t sense the enormity of its impact. It’s clear to me now that it triggered the white exodus out of New York, along with a great re-segregation and atomization of society on many different levels.

The multi-decades lease on the Luxor was drawing to an end. My father attempted to purchase the property on a couple occasions, but I don’t think he had the entrepreneurial drive to make it happen. He always knew that the baths weren’t a good business model. Ideally, he would have reserved four floors for the Luxor and remodeled the remaining five floors into office space. That way he wouldn’t have to run the baths 24 hours a day, all year long.

The big real estate operators in Manhattan eventually purchased the Luxor. Their ultimate goal was to cobble together a collection of properties on 46th and 47th streets and redevelop the area. I seem to recall the names Goldman and Durst. I believe that my father’s group had an option to renew that wasn’t honored, or perhaps they violated the terms of their lease. My cousin Gil, my Uncle Willie’s son, represented the Luxor in court. He told me the judge said, “I can’t go up against these guys, they’re too powerful.” Gil told me he had never heard a judge say something like that in open court.

For the first time in decades, my father was out of a job and the Luxor was out of our lives, or so we thought. Fred Epstein might not have been driven to acquire great wealth, but he was competent. He could hold a business together with scotch tape and bakery string if he had to. It seems that the Durst organization couldn’t make the Luxor work and they asked my father to come back and run it. They had no intention of keeping the Luxor, but they didn’t want to bleed money either.

But it was never the same. The Broadway area was now seamy and downright dangerous. There were never any anecdotes from my father, but I could tell that he hated going into work every day. And it was time to leave New York too. A friend’s nephew had started an auto parts wholesaling business and needed an experienced inside man. My father took the job, which he enjoyed, and started the process of packing up and buying a condo with my mother in Florida. I had been awarded a graduate research fellowship from the Japanese government and missed most of this chapter.

Once my parents relocated to Florida, I ceased to visit New York. All my boyhood friends were scattered across the country and the city was no longer Cary Grant’s New York in North By Northwest, but Charles Bronson’s in Death Wish.

I returned to New York in the mid 1990s. It was the in the midst of the Giuliani Renaissance. It wasn’t until I decided to commit my remembrances to paper that I learned that in the end the owners of the Luxor were accused of running prostitutes through the place. It appeared that the anonymity that the Luxor conferred on its habitués had been so successful that only the references to its ignominious demise remained. 121 West 46th Street no longer exists. What was the Luxor is now the back of building that fronts on 47th street. So I decided to set things right and let people know that I was redeemed at the Luxor Baths.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

______________________________

Marc Epstein is the author of ‘The Historians and the Geneva Naval Conference’ in Arms Limitation And Disarmament: Restraints On War, 1899-1939, edited B.J.C. McKercher, Praeger 1992. He has a PhD in Japanese diplomatic history, specializing in naval disarmament in the interwar years. His articles have appeared in Education Next, The American Educator, City Journal, the Washington Post, New York Post, and New York Sun.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast