The Meritzine Palace by Ghislain de Diesbach

Translated from the French

by David Platzer (October 2021)

Ghislain de Diesbach, born in 1931 in Le Havre, is best-known in his native France for his acclaimed biographies of Proust, Chateaubriand, Madame de Stael, Marthe Bbesco, as well his history of the Emigration of French aristocrats during the Revolution and the Napoleonic Era. Nevertheless, his fiction is dearest to his heart. “The Meritzine Palace” as “Palais Meritzine” is in his collection of short stories, Au bon patriote, published in the original French by Plon, in Paris, 1996.

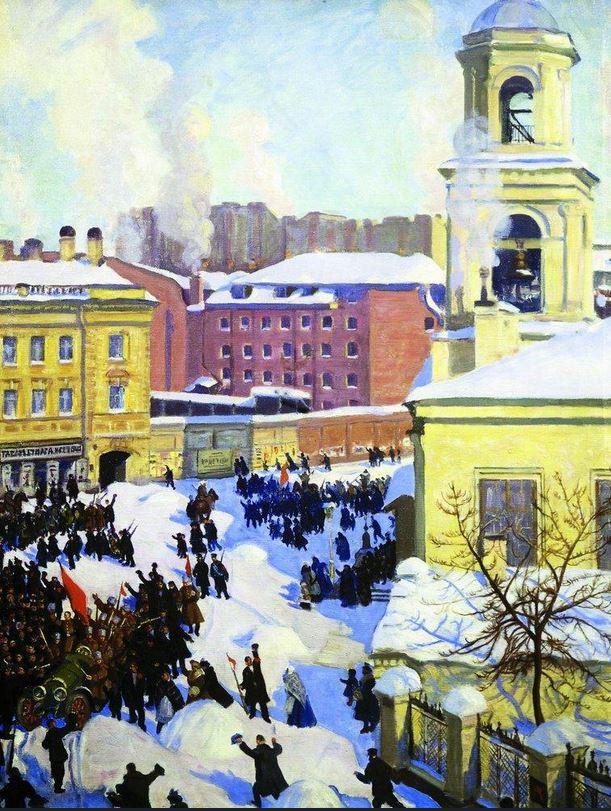

In the palace in the Nevsy Prospect, the Prince and Princess Meritzine, surrounded by their children and their servants, were impatiently waiting to be assassinated. Since Saint Petersburg had fallen entirely into the hands of the Reds after eight days of battle, the Meritzines had lost all hope of salvation, and had stoically resigned themselves to the inevitable, preparing themselves to martyrdom by chanting the canticles. Prostrated before the holy icons, they prayed to the Lord. Saint Anne and Our Lady of Kazan to assist them in this supreme trial.

The great position the Prince held at court, his political role in the latest events, his palace’s ostentation and his reputation for charity all designated the Meritzines for popular resentment. The Meritzines were astonished though not unduly exercised when several neighbouring palaces were sacked, their occupants defenestrated, or taken to prison. The spectacle that the Meritzines contemplated from their windows had frozen them with horror and to avoid prolonging uselessly their agony they decided to offer no resistance. Only the English governess and the French tutor put a discordant note in this pious concert. Damning the fate that had brought them to this moment, they energetically refused to play the part of martyrs and looked for a way of getting out of this affair.

While the telephone was still working, Miss Southernay alerted the British Embassy and asked for its protection. She hoped that help would arrive rapidly and, if it did, she would leave at once. Sitting very erect on a chair, her overcoat’s collar buttoned up to her chin, and her hands gripping her umbrella’s handle as if was a sword’s knob, she seemed more discontented than alarmed. At her feet was a tapestry bag which contained her most prized possessions. She had put on it a little British flag, the sight of which she hoped would deter the Reds from their vigour. Should it reveal itself insufficient, she intended to make a murderous use of her umbrella.

M. Lormay, the preceptor, was dismayed by the fatalism shown by the Meritzines in accepting a hideous death rather than making the slightest attempt to escape it and he, in the same way of Miss Southernay, was ready to defend himself to the end. He had taken down from the vestibule’s panoply a Kirghize shield and he practiced handling a gigantic kitchen chopper, more dangerous to himself than to any assailant.

This situation lasted for more than twelve hours, during which time the Meritzines, bolstered by their faith, chanted magnificently. Nevertheless, it was a wait that began to try even the most patient dispositions and a certain disorder began to manifest itself. The younger children slept, sprawling on their heels while their elders argued. Princess Natasha, one of the prince’s daughters, accused her brother Andrei of singing out of tune, the better to make everyone laugh. The guilty party protested his innocence by weeping. Everyone was hungry because all the provisions were exhausted; the cold made itself felt since the heating had gone from a lack of combustible. The princess, particularly tried by the nervous tension that reigned, could not control her nerves. She burst into tears and, in a drowning voice, said to her husband:

“Do you not find, Vladimir Alexandrovitch, that it is cold enough here to freeze one to death?”

When the prince in his surprise, remained silent, she repeated:

“Vladimir Alexandrovitch, I can’t bear it; I can’t go on; I want to go; I want to go home!”

In her trouble, she expressed herself in Italian. The servants, astonished to hear this language unknown to them, stopped their whisperings to hear their mistress unfold this plaintive chant:

“I want to leave,” she repeated, “I want to go back to Naples…”

It was in Naples that the prince had met her during a trip. He had married her on an impulse, just one buys a trinket in a shop of souvenirs. Very quickly, he had wearied of her even as he made sure that she gave to the Meritzines a new member every other year. Divided between his mysticism and his taste for very young girls, he expiated his long retreats in monasteries for his life as a libertine. His wife consoled herself with spiritualism and social life. For the moment, she dreamed of turning the tables and, between her tears, bitterly reproached her husband for not having taken refuge in the Crimea where he possessed a vast domain on the banks of the sea: “There it is warm, there are palm trees, flowers and sun! To think I shall never see again Naples and Sicily, that I shall never again walk under the orange groves of Saint Agatha … It is too awful! Vladimir, you cannot know what it is like for me! I have the impression that I am going to die twice … Why were we not been killed in that riot in Syracuse in 1908? Do you remember it, Vladimir? The weather was so delicious that day.”

And with this evocation, the Princess began to cry again.

“Come now. Silvia Nicolaievna, be reasonable! Don’t make such a scene in this way,” said the Prince with the bored air of a husband whose wife is making a scene in a restaurant. “It is a bad moment for us, I admit, but think of our children and our servants to whom we have to give an example. Remember that in France the aristocrats died bravely on the scaffold. We must conduct ourselves as well as they did … But it is certain that it is cold,” he admitted. “Here, Silvia, drink a little vodka, it will do you good.”

He went to get a flacon on the console only to find it was empty.

“Nikita,” he said to one of the servants, “go and get some bottles of brandy and vodka.”

The tutor applauded this idea and offered to accompany Nikita. As they were going out of the great salon, violent blows exploded downstairs at the door of entry.

“They are here! Here they are!” cried the Princess, terrified with fear.

All of them threw themselves on the ground, their arms crossed in postures of sacrifice. The blows ceased. Everyone stopped chanting so they could listen…The blows started again.

“It is not the Reds,” said the tutor. “It is a knocking on the door which the savages would have already broken. It is perhaps someone asking for asylum.”

“It is me whom the Embassy are coming to rescue!” exclaimed Miss Southernay, getting up and waving her little flag.

“We must open,” said the Prince. “Go and do so, Nikita.”

“Don’t go,” the Princess moaned. “It is them. I am sure of it.”

“Go and see, Nikita,” ordered the Prince with impatience.

Nikita went down. Listening closely, those upstairs heard sounds of discussion followed by the long opening of the heavy door. A man’s voice murmured some words and then a feminine voice, clear, strident and happy, filled the entrance hall. “Eh! Vladimir Alexandovitch! Silvia Nicolaievna! How are you?”

“It is Sophia! That madwoman, Sophia Koranev!” the Princess cried distracted in an instant from her despair. “What is she doing here? I thought she was in the Crimea.”

Preceding Nikita and a very strong-looking and bearded individual who looked to be a Russian peasant from the steppes, appeared Baroness Koranev, perky, light-hearted, agitated, her waist tied in a redingote of grey cloth, a dark astrakhan bonnet, a little off-kilter over her dyed hair, and shod by ankle boots whose pounding pace echoed the dance step she sketched as she made her entrance. She took off her little coat, threw it on an armchair and extended her two hands as she rushed to the Prince. “You remind me of the Grand Duchess of Gerolstein!” he said to her as a way of welcome.

“And all of you, you seem so lugubrious! What has happened?”

“I was going to ask you that?” the Princess intervened. “What is the situation outside?”

“It is desperate, it is lost but it is not all that dire!” the Baroness said in a tone that was reasonably gay. “I think the capital is in the hands of insurgents for I have not been able to go further than you. I saw in the middle of the Perspective a band of scruffy soldiers who seemed fairly louche and I rushed to take refuge here…”

“But what in the devil made you go outdoors? It is madness! And who is the person who is with you?”

“It is my bodyguard, an old bear-hunter gifted with a herculean strength. He can strangle a man as easily as you could a kitten. I always go out with him and I am left alone: no one dares ask my papers!”

“You have not told us where you are going.”

“I am going to find what kind of state my uncle Ouremsky’s house is … Speaking of that, congratulate me, my dear, congratulate me.”

“For what my poor friend? What kind of happiness could reach you in this time of troubles?”

The Baroness proudly pulled herself up:“I am now the best match to be had in Saint Petersburg!”

“What do you mean by that?”

“Yes, I learnt yesterday morning of the arrest of my dear uncle, the old General Ouremsky. In the evening, he was shot to death as an enemy of the people, leaving me at last the owner of his fortune which I have waited twenty years to get … I hope at least to save the domains in the Crimea which are considerable.” Lowering her voice, she spoke to the Prince: “You see, you handsome inconstant, what could have been yours had you the patience to wait for me! Think what we should have today with my fortune and me!”

The Prince could not resist a smile:

“You haven’t changed, you are always the same, Sophia Feodorovna, reckless and gay. But I could remind me,” he continued, switching into German so that his wife would not hear, “that it was you who showed inconstancy. Why did you marry that old loon, Koranev?”

“Oh, Vladimir, you cannot be talking seriously! That was a mere caprice, a fantasy, you knew that very well and we were hardly more married for a year! That hardly counts! I assure you that everyone has forgotten it…”

“You married before I did, is it not true?”

“Do be quiet, jealous man. It was your fault.”

“My fault! To listen to you…”

“Very well, listen to me then…” And the Baroness Koranev seized the Prince’s arm and drew him into a corner of the salon. “Do excused us, Silvia Nicolaiiavna,” she said to the Princess, “we have to talk about business, Vladimir Alexandrovitch and I, the succession of the general is so confusing!”

“But what can I know about your uncle’s succession?”

“It is not about my uncle and his succession that I wanted to talk about … Are you still always naïve? I wanted to talk to you privately without Silvia being able to hear us. When one wants to talk to a man whom one loves,” she added, pointedly, “one cannot do so, it seems to me, in his wife’s presence.”

“What are you talking about, Sophia? What are you telling me?”

“Nothing extraordinary or new, Vladimir Alexandrovitch, only that I love you still despite our mutual infidelities. It is you I should have liked to marry. Once married, I saw the error I had made and you in your turn, committed your own in bringing back from Italy your little bird. We have wasted our lives in a stupid way but at least we shall not waste our deaths! If I have come here today, it is to see you one last time and perhaps die with you, because I am not ignorant of the fate that waits for us. When I was thirteen, I loved you already, and, often I imagined dying for you, of dying one day near you, my head against your chest … That dream was without doubt, a premonition of what is going to happen soon…”

“Truly, Sophia, you loved me already and so young?” the Prince murmured and grew tender at his memory of the little young blonde girl he had known. “You never told me!”

“The feelings of children, above all when they are sincere, always seem ridiculous, and I should have died of shame to have avowed mine. Now it is so far away … and our end is so near! Listen, Vladimir. I think I was touched by you in 1886 in the party that the old Countess Narischkine gave in her park … Do you remember it? You were eighteen and were going out of the Court of Pages. You were with your comrades and you were chatting with them without paying any attention to the group of young girls, hardly more than children, escorted there by their mothers and blushing with shyness. Each of us had a favourite among you and I feared that you were already taken by another girl! I asked Tatiana Schakovovskoy your name and, as a joke, I cried it behind an orange tree. Surprise, you turned on hearing your name called: it was that instant, I believe, that I truly loved you, when I encountered for the first time, your regard…”

“Dear Sophia Feodorovovna, you have an imagination that is much too vivid. One can’t seriously love anyone at thirteen.”

“And aged twenty, one loves better? I hope so, Vladimir, since if I had not had the conviction that you loved me at that age, not for a long time, it is true, I should not have come here this evening … Is it not so, Vladimir Alexandrovitch, that you have loved me?”

“I have never forgotten Sophia Feodorovna, that marvellous summer that we both spent at Jablonowska. Never without you should I have been able to bear that exile in the country that my young man’s escapades had earned me.”

“Yes, I know,” said the Baroness with a hint of sadness, “in the country, a summer of love is less a feeling that an occupation. Had I not been there, you would have courted one of your aunt’s chambermaids and it would have been the same to you.”

“But no, Sophia, you are being silly! Get off it! I sincerely loved you; I should have gladly married you even without your lack of fortune. Do you remember? Was it my fault that you had to go and marry that silly ass, Koranev?”

“Yes, it was your fault. Vladimir, you could have stopped me, you could have carried me away in a coach, a horse, a balloon, what do I know? Anything to prevent me from making that mistake. If I finally married Koranev, it was only with the idea of making you jealous; and then, it is easier for a woman to deceive her husband than for a young girl to compromise herself. I did not want to harm your career because I was without fortune but once I married Koranev, I could have become your mistress … It was the greatest joy I gave myself to that poor Ivan Ivanovitch; I owed him a sincere obligation,” she said, laughing. “Now, Vladimir, let us not spoil the present, sad as it is, in going over the past; we have perhaps only a few hours more to live … Let us enjoy ourselves the best we can. Why not celebrate my inheritance? You still have champagne, I suppose?”

“Yes, but it seems hardly the moment to be drinking champagne, it seems.”

“It is just when circumstances are less than droll that one has to lighten them. Come on now, go down to your cellar and get some bottles of champagne and glasses.”

“You are extraordinary, Sophia, for I fear that this will not be to my wife’s taste.”

“Don’t worry, I shall try and convince her!”

The Baroness got up and walked across the room and, addressing the Princess, declared:

“Do you know, my dear, your husband has had a marvellous idea? He has just ordered from the cellar champagne so we can celebrate my inheritance and recall for one last time, the good old days. What do you think about that?”

“That seems an idea that he would have,” the Princess said in a plaintive voice. “Amuse yourself if that is what you want. For me, I prefer to prepare myself for death in another way.”

Nitika and another valet went down to the cellar and two chambermaids went to fetch the glasses.

***

A quarter of an hour later, the Baroness Koranev. The Prince Meritizine, his son and the tutor were drinking with enthusiasm. The Princess Silvia, her daughters and Miss Southernay regarded this scene with a disapproving eye. The servants, interrupting their prayers and lamentations, were sitting in a demi-circle before the chimney. The Baroness Koranev indicated them to the Prince:

“We should give them champagne to them too.”

“I don’t think so,” he said with indignation. “It is Moet & Chandon 1909 one of the better vintages.”

“Do you prefer it to be drunk by insurgents, already too drunk to appreciate it?”

“You have a point,” the Prince admitted, “but the servants wouldn’t appreciate it either. They have never drank and I don’t want to see them drunk in an hour.”

“But is so amusing when servants get drunk!” said the Baroness, laughing. “The other day I got my coachman drinking to console him for the loss of his horses which were requisitioned. In a fit of euphoria, he took me in his arms and swore to defend me against the Reds … I had all the difficulty in the world to get him off me!”

“I have the impression, Baroness, that you have already drunk too much,” the Princess observed with a glacial tone.

“But no, Silvia, it is you who have not enough to drink! Come, give me pleasure and accept a glass!”

The Princess obeyed with ill grace. She took the glass and swallowed in a single gulp, and then threw it into the chimney where it shattered.

“What have you done, Silvia?” asked her husband, taken aback.

“I am drinking in the Russian way, my dear … is that not the way Russians drink? You see that I have come to adopt your country’s habits. Better later than never…”

Saying that, she took another glass, drank it and equally broke it after emptying it. The Baroness Koranev clapped her hands with enthusiasm.

“Bravo. Silvia! Come, Vladimir, give champagne to all of your people and let us all drink in the Russian way!”

Nikita brought up other bottles which were welcomed with joyous exultation. Other glasses were supplied and soon the chimney was full with shattered glass, sparkling and cracking. An hour later, a great effervescence filled the palace’s salons. At the Baroness’s request, all the candles in the chandeliers were lit and the champagne on empty stomachs, produced a buoyant effect.

The Princess reprised with a nervous laugh that prevented her from taking her song to the end, the refrain of a Neopolitan song which she repeated without wearying. Prince Feodor beat his sister, Princess Natascha who cried without anyone paying attention. Two other of the Prince’s sons, scarlet-faced and petrified, devoured with their eyes, a young chambermaid who had put herself as ease, champagne having given her the vapours. Miss Southernay, followed the Princess’s example, and after third glass, was in a state of intense patriotic exaltation. Sitting on her armchair, she waved her little flag chortling: “Hurrah for England! England forever!” The majority of the servants were laughing at their masters’ extravagances and some of them tried imitating them in rather clumsy ways. An old butler and his wife sketched a dance step but slipped on the paving and would have fallen twenty times had not the Baroness’s moujik grabbed them with a vigorous grip. The French tutor told racy tales to one of the young princesses who didn’t understand them though they much amused Prince Vladimir, too tipsy to be indignant to hear lessons of immorality being told to his daughters. Only the Baroness kept a cool head and to the Prince who seemed surprised, she replied:

“Alas, my dear, I have been trained … I regret having solid a head since there is nothing more agreeable than to let oneself go a little…” And she drank methodically in the hope of reaching that goal. In the same way as the Princess she threw her glasses in the chimney, repeating each time:

“One more that the Reds won’t get!”

“And they won’t get these either!” the Prince cried in pushing two enormous china vases which smashed into a mess with a great noise from the console on which they had stood. At the sound, everyone became silent.

“What has happened?” the Princess asked.

“I broke Aunt Olga Dimitrievna’s vases,” her husband said, scoffing.

“I hope she has not hurt herself,” said the Princess, whose thoughts were more and more confused.

“They were too pretty and I did not want the revolutionaries to have them.”

The Prince’s regard travelled round the salon in search of objects he wished to save from the popular fury. “You see, Silvia, they must not have all of these … or those,” he said, his voice muddy and since in this drunken moment, he was having difficulty in finding his words. “We cannot let all of this fall in the hands of vandals: they must have nothing!”

In a moment of anger, he attacked miniatures hanging on one of the wood panel walls and smashed them savagely.

“Stop, Vladimir Alexandrovitch,” the Baroness, alarmed by this unforeseen rage, said to him, “those miniatures are priceless.”

“I shall leave nothing to them!” he continued without listening to her.

“Oh Vladimir, I do understand, but it is such a pity to break all of these lovely things!”

“Do you prefer that the Reds break them?” he asked “They will break and sack everything, you know that very well.”

“Yes, I know but it seems impossible that they would ever touch this salon. Do you believe that even the insurgents would dare brave the great Meritizine’s regard?” she said theatrically in pointing to the Field Marshal who had vanquished the Turks in the Crimea. “Even the Great Catherine trembled before him!”

“Don’t listen to Sophia, she is completely crazy,” the Princess interrupted. “I don’t want them to have my things either nor my Capodimonte service…”

Without finishing her sentence she went to the window cabinet which held the precious service, a present from a Queen of the Two Sicilies to one of her ancestors. She was unable to open it and so she took a yatagan sabre whose blows had felled Prince Gregor Efimova Meritizine in 1752, and charged the cabinet with fiery gusto. Soon, there remained nothing of the porcelain service but a mess of coloured debris and the Princess, waved her arm triumphantly, singing:

“Here stands the sabre, the sabre, my father’s sabre!”

This execution was the signal of a general rush to the salon’s furniture. In the same way that fire gushes brusquely over a household, a mad folly of destruction took hold of the Meritizines and their employees. All of them precipitated to break the objects of value.

“Let us leave nothing to those savages!” the Princess repeated hacking with frenzy the tapestries done with fine needlework on the Louis XV armchairs bought by a Meritizine at the furniture sale at Versailles during the Revolution.

Miss Southernay, having abandoned her flag, went to work on the paintings with her umbrella. For those too high for her reach, she stood on a chair but when even that expedient was not enough to get at the portrait of Field Marshal Igor Vassilievitch, she climbed on a lacquered Secretary, aided by a wine waiter. The latter refused his hand to help her climb down and the wretched woman was obliged to remain perched there, her legs dangling and her umbrella in her hand. Far from feeling afflicted by this situation, she appeared to enjoy great pleasure in it and she put herself to humming Victorian melodies inspired by the Lake poets.

Prince Feodor, who had stopped beating his sister, attacked the curtains on the windows, breaking their glass. One of the curtains in falling, caught a rod that had supported it and knocked him out. His two brothers, moving from contemplation to action, chased a young maid through the salons, hitting everything in their way. Princess Natascha, three-quarters of her body nude, jumped on a cord onto a pink satin pouf where her sister, overtaken by French gallantry, was kissing and embracing M. Lormay while tenderly reciting irregular verbs. Helped by those servants were still able to stand on their legs, Prince Vladimir Alexandrovitch was taking all the furniture from the salons and throwing them down the staircase’s cage. Baroness Koranev stimulated their zeal in giving them more to drink. Her bodyguard gave himself to Bacchic improvisations of the greatest indecency and with great cries to rape her.

When all the treasures in the salons had been completely sacked, the little band roamed through the palace to continue the work. Princess Natasha invaded the music room on her own and, armed with a dessert knife, went to pull out the piano keys, one by one. She brought to this work a Chinese executioner’s application in ripping out his victim’s fingernails. The two brothers, seduced by the maid, managed her to corner in the Princess’s bedroom and gave her the honours of their mother’s bedroom. Their mother herself, in the grip of a very Italian jealousy on seeing one of her daughters in the tutor’s arms picked up Miss Southernay’s umbrella and hit violently the lovers who ran to take refuge in another room. Dishevelled and crying vengeance she pursued them and only was disarmed when M.Lormay abandoned her daughter to attend to her needs. Having exhausted her repertoire of Victorian melodies, the Englishwoman had fallen in ecstasy before the mutilated portrait of the Field Marshal and shaking her head in sadness repeated: “Poor young man! Poor young man!”

The servants, spread through their masters’ rooms, joyfully sacking them after years of respecting them. Some of them rigged themselves up in gowns and suits they had in the past hung in wardrobes. Soon several Princes Vladimir and Princesses Silvia were wandering in the palace’s corridors, staggering and singing, aping their masters and offering cruel caricatures of their august personages. A kitchen maid simpered behind a fan and wished forcefully that the Princess make for her a bortsch. The Prince’s personal valet looked everywhere for the great Cordon of the Black Eagle so he could attach his wife at the foot of his bed and declare haughtily that as from tomorrow, he would flank at the door those good-for-nothing valets.

Having taken refuge in the attics, the Baroness and the Prince found in this modest décor, the atmosphere of that unforgettable summer of 1886 and the Prince, swearing eternal fidelity to the Baroness, promised her that he would demand her hand from the Emperor.

***

When the Reds invaded the Meritzine Palace towards four in the morning, they were convinced that an alternative band of vandals had got there ahead of them. There was an incredible array of dislocated furniture at the great staircase’s bottom. Innumerable cadavers of bottles were to be found on the paving and Nikita, seized by violent stomach pains, had expressed himself in the pots of the palm trees in the winter garden. Everywhere, in beds and even on the rugs, couples lay, dead drunk, and on seeing the Prince Feodor snuggled in the arms of his father’s old nurse, the band’s leader burst into laughter. He rallied his troops which had searched in vain for something to pilfer and then left the scene.

The cold revived the heroes of the orgy. The Princess was the first to gather her senses and, leaving the tutor to his snores, regained her bedroom to perform a little toilet. Great was her shock on discovering her sons sleeping, tenderly entwined in each other’s arms, in her bed: the young chambermaid had disappeared and, ignoring this essential detail, she considered, not without pain, this tableau which offended her sense of morality. Finding her husband and the baroness in each other’s arms astonished her less. She pulled the couple out of their guilty sleep and they held a quick council as to what they should do. The Baroness thought they should leave in all haste before the domestics emerge from their slumber:

“They can always pass themselves off as victims of the aristocracy,” she said, “and no one will bother them. For us, we must look for a less exposed refuge and from there, try to leave for the Crimea…”

“And we shall not die!” the Princess cried with a vivacity that betrayed intense satisfaction. She had, in effect, changed her mind and henceforth, wanted to live and know again the delicious pleasures into which the tutor had initiated her.

“I very much hope so!” the Baroness added. “Yesterday evening’s comedy was silly.”

“In any case, I must wake my children and dress…”

“Keep yourself dressed as you are,” the Baroness said.

“What, in this torn and stained gown?”

“Exactly! This get-up will be the best safe conduct. Trust me. We must remain as we are and take only some old furs and overcoats from the servants. That will[DP2] make us seem rioters. That will be perfect!”

The Meritzines, on discovering that the great door with its double locks had been broken and the Reds had come during the night, measured their luck to have escape. Thanks to relations, equivocal but influential, of the Baroness’s, they were able to escape Saint-Petersburg, on a train of goods. After first taking refuge in London, the Meritizenes then fixed themselves in Paris, where they were admirably welcomed by a society by whom the misfortunes of white Russians were a source of picturesque tales and comfortable emotions. They were ceaselessly invited to dinner so they could tell in detail of Bolshevik atrocities as well of their escape.

“And so, dear Princess, you were present at the sacking of your palace which took place under your own eyes?”

“Alas, yes, under our own eyes. We were not spared the hideous spectacle. You have no idea of the savagery of these creatures. We saw our collections, our family memories, our most precious furniture destroyed by a band of frenzied bandits. They wallowed in our beds, ripped our tapestries, and pierced our paintings with bayonets … ah, how can one survive such horrors!” The Princess closed her eyes in an attempt to forget this vision that would haunt her for the rest of her days.

“You must have a little more champagne,” said our host, eager to dissipate these painful memories and restore a little verve to the Princess.

“Gladly,” she said with a feeble smile. “I adore champagne as all Russians do!”