The Poets of the Felix Dzerzhinsky Guards Regiment

by Peter Dreyer (May 2022)

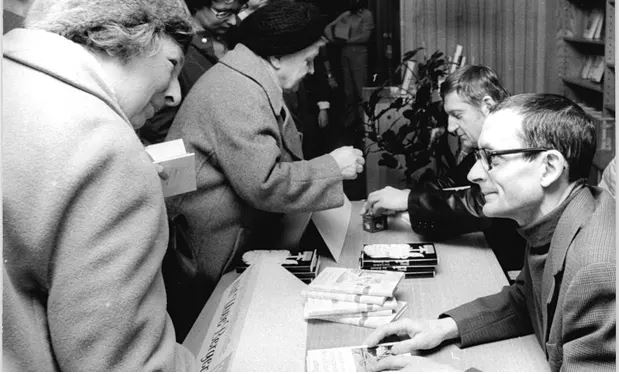

Uwe Berger at a book signing in Berlin, 1975. (Photo: Rainer Mittelstädt/Bundesarchiv)

Taken prisoner in 1945, when he was just 18, Bernhard Elsner spent the next five years in a Soviet POW camp. Released, he joined the People’s Police, or Volkspolizei, VoPo for short, in what presently became the German Democratic Republic (DDR). He throve as a policeman, and by the 1970s, he commanded the elite Felix Dzerzhinsky Guards Regiment (FDGR; Wachregiment “Feliks E. Dzierzynski”), the paramilitary wing of the Ministry for State Security (or Stasi). Although called a regiment, this entity expanded to the size of a motorized infantry division and was some eleven and a half thousand strong when eventually dissolved in 1990.

Major-General Elsner was to preside inter alia over an astounding development: the creation of a VoPo poetry circle.

In the spring of 1972, I was drinking coffee at an Autobahn café on the Hamburg-Berlin highway in the former DDR, when a VoPo squad barged scarily in, looking and acting for all the world like a bad dream out of a World War II movie. The cut of their field-gray uniforms and peaked caps screamed: Polizei! Gestapo!

But poets?

The “Working Circle of Writing Chekists” (Kreisarbeitsgemeinschaft schreibende Tschekisten) met regularly at the FDGR’s Adlershof headquarters in the 1980s to discuss and read their poetry. They called themselves Chekists after the legendary Cheka, the “All-Russian Extraordinary Commission,” headed by Lenin’s ruthless enforcer “Iron Feliks” Dzerzhinsky (1877–1926), the representative of what he himself called “organized terror”: mass summary executions.

But these East German “Chekists” were not real Chekists, of course, although there were many such (after several incarnations, the Cheka had morphed into the KGB) in the DDR as liaisons with the USSR. Among these, we might note young Vladimir Putin, then based in Dresden. He probably wrote poems too.

Would it be going too far to suggest that the German leftists were suffering from a combination of PTSD and what is called Stockholm syndrome? They had been decimated first by the Nazis and then by the Kremlin. More members of the Politburo of the German Communist Party were shot in the Soviet Union, where they had taken refuge, than in Hitler’s Germany. In the aftermath of the war, men like Elsner could hardly have known whether they were coming or going.

The DDR was the Kremlin’s “model student,” the West German newspaper Die Zeit noted in 1974. “No other state in the communist world has submitted itself so unconditionally to Moscow’s leadership.” But when Mikhail Gorbachev, elected as General Secretary of the USSR in 1985, launched his twin policies of glasnost (transparency) and perestroika (restructuring), that changed: the Party paper Neues Deutschland ran an article defending Stalin against Gorby’s reforms, and in 1987, the East German government actually began censoring Russian publications. We all know how things turned out in the end for the DDR.

So what was the “Writing Chekists” poetry like? In his fascinating study, Philip Oltermann unfortunately quotes it only in translation (presumably his own), which makes it difficult to judge:

My father is a Chekist.

It is hard to see through

everything he does when he is there

but rely on him I do. (Rolf-Dieter Melis, “My Daddy”)

The German original might no doubt give a better idea of this too:

I have been empowered

to delegate power

That has to take me into account.

This makes me mighty (Alexander Ruika, “In My Power”)

However, there was inevitably one thing absent from much of the work of the “Writing Chekists.” True poetry is always in some sense enigmatic. Lacking the freedom to chase after life’s mystery, poems likely cohere only in doggerel.

Toward the end of the DDR, a young officer in the Stasi’s propaganda unit couldn’t take it anymore: “East Germany was a touch of a button away from all-out nuclear war, and his colleagues thought they could just ‘crawl out of their holes’ afterwards.” In June 1984, he read a long epic on theme of the nuclear annihilation of humanity to the poetry circle:

Karl Marx tries to make a plea

looks Odysseus in the face

Says gravely:

They’re doing it because of me

But they put their faith in the wrong place.

I drag myself

for weeks on end

and stumble all alone

no longer through hills of rotting flesh

but mountains made of bone. (Gerd Knauer, “The Bang”)

The circle’s leader, Uwe Berger, decreed this to be nothing but “idealism and acceptance of surrender” on the part of “Comrade Knauer and his uptight, pig-headed personality.” Berger concluded that “he was dealing with a professional sabotage attempt. Knauer . . . was ‘systematically obstructing the Circle of Writing Chekists.’”

In an earlier era, Knauer’s fate would no doubt have been grim! But nothing much seems to have done to punish him by his superiors in the Wachregiment. After the collapse of the DDR, he changed his name, and when last heard of he worked as a tax adviser, inter alia, to former senior officers in the Stasi. Perhaps not the most appealing fate for a poet, but it could have been far worse.

The “Bang,” of course, still, once again threatens us all. And once again certain people (no need to name them) apparently appear to think they can “just ‘crawl out of their holes’ afterwards.” As Talleyrand said of the Bourbons, they’ve forgotten nothing and learned nothing.

Peter Richard Dreyer is a South African American writer. He is the author of A Beast in View (London: André Deutsch), The Future of Treason (New York: Ballantine), A Gardener Touched with Genius: The Life of Luther Burbank (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan; rev. ed., Berkeley: University of California Press; new, expanded ed., Santa Rosa, CA: Luther Burbank Home & Gardens), Martyrs and Fanatics: South Africa and Human Destiny (New York: Simon & Schuster; London: Secker & Warburg), and most recently the novel Isacq (Charlottesville, VA: Hardware River Press, 2017).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast