The Rise of Jerusalem

By Friedrich Hansen (January 2018)

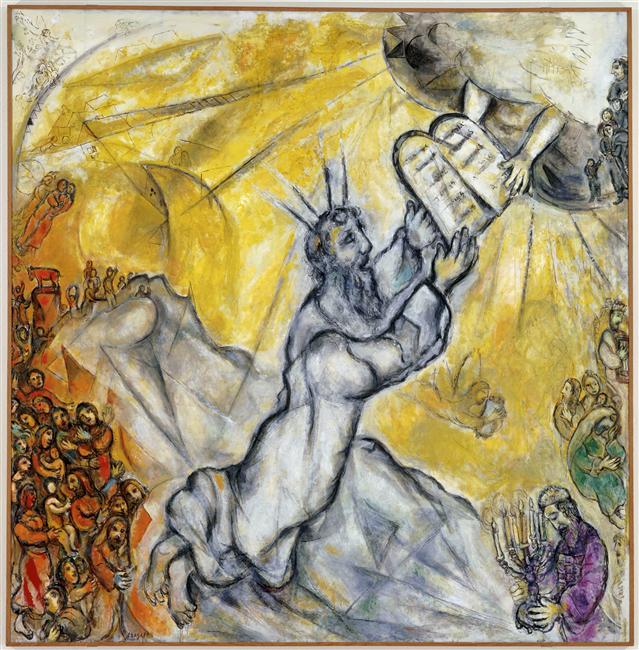

Moses Receiving the Tablets of Law, Marc Chagall, 1966

.jpg) ith Jerusalem on track again after millennia to becoming the acknowledged capital of the Jews, major politico-theological changes are upon us. Just as the increasingly fragile EU rescued Athens more than financially and is seen by many as itself in need of something to hold on, Donald Trump wholeheartedly embraced its old rival Jerusalem. No surprise then that the announcement by President Donald Trump that the United States will move its embassy to the holy city was met with immediate rejections by the Arab League in sync with the European Union—with the notable exception of Czech Republic and Hungary. It is no coincidence that the rejectionists belong to the club of the last universalists, even if they reside on the opposite ends of the political spectrum: liberals vying with fundamentalists. This must be put in the context of the recent Renaissance of particularism and nation states which is driven by disappointment by the Davos elites. In addition, the hype of gender diversity has awakened the silent majority from the slumber of enlightened identitarianism and is fostering the longing for self-determination. It is for this reason that basic democratic concepts such as referenda and populism have surged recently.

ith Jerusalem on track again after millennia to becoming the acknowledged capital of the Jews, major politico-theological changes are upon us. Just as the increasingly fragile EU rescued Athens more than financially and is seen by many as itself in need of something to hold on, Donald Trump wholeheartedly embraced its old rival Jerusalem. No surprise then that the announcement by President Donald Trump that the United States will move its embassy to the holy city was met with immediate rejections by the Arab League in sync with the European Union—with the notable exception of Czech Republic and Hungary. It is no coincidence that the rejectionists belong to the club of the last universalists, even if they reside on the opposite ends of the political spectrum: liberals vying with fundamentalists. This must be put in the context of the recent Renaissance of particularism and nation states which is driven by disappointment by the Davos elites. In addition, the hype of gender diversity has awakened the silent majority from the slumber of enlightened identitarianism and is fostering the longing for self-determination. It is for this reason that basic democratic concepts such as referenda and populism have surged recently.

To my knowledge, it was the apostle Paul who invented universalism as the Christian brand of Catholicism (which means the same thing) by alienating Jesus from his Jewish roots consisting of strong families tied to religious inwardness. Jewish hope culminates in the never-to-be-arriving Messiah, which is why scores of Hebrew verbs, like in English, gravitate towards “becoming” rather than the Greek and German “being”. The former belongs to the mentality of traders while the latter represents the mentality of craftsmen. This is being corroborated by the strong centripetal orientation of Jewish particularism. It culminates in the “ontological pull” of Hebrew grammar conducive to transcendence and extremely avers to mirror thinking and metaphysical reification. By contrast, Paul would be abstracting from the particular, wedded as it is to the unique Jewish person, whereby he would vaporize divine transcendence.

The dismal effect of Paul’s Catholicity is this: he redirected all projections and prejudices between individuals from inward transcendence tied to the auditive paradigm toward outward immanence issuing from the visible paradigm. The result of this universalist manipulation which works, by the way, as an extinction of meaning intelligible to the faithful subject, was drawing all class and ethnic projections toward the one-proxy scapegoat called Christ. By comparison, Judaic inwardness was meant to deal with homegrown evil personally and stay clear of any redemption by proxy or scapegoating. The latter was the rule in late antiquity, dominated as it was by Greek shame culture. This much was understood by Sigmund Freud very well, who was appalled by rampant anti-Semitism in pre-WWI Vienna. As a result, Freud would analyze projections as a mendacious psychological mechanism. With that he accomplished a self-enlightenment of the “persecuting innocence”, the flip side of Christ as eternal victim.

Nevertheless, modern victimology became ubiquitous and remained the bane of secularized Christianity. The gravity of this European nemesis is on full display only today while the rapid abandonment of Christ is about to unleash hell onto Israel as the global scapegoat. And yet, already in antiquity the reconstructed Pauline Christ, by contrast to the Jewish Jesus, was a centrifugal universal Type, alienated from family and hence prone to missionizing and speech codes that turned piety outward as a matter of show. Inward Judaism and Orthodoxy, by comparison, stuck to married priests wedded to the family. As Philip Rieff observed, the Greek-Oriental hybrid called Christ was self-contradictory, half man and half God, who actually internalized the tension between the universal and the particular often in an antagonistic fashion which sometimes results in suicide or gender dysphoria. This is why very early on and lacking the protection of the family, St Paul had to resort to concepts of group protection similar to modern multiculturalism and diversity. The enduring symbol for this is the faceless hood of the Christian monk and the modern automaton lefty, his personhood weakened by typological identity, which often confused sexual orientation in waves of group mania.

As an intellectual category free-wheeling universalism stands in principal opposition to the particular Jewish divinity and subsequently loses the capacity to neutralize anxiety, a mechanism thoroughly analysed by Soren Kierkegaard.[1] Paul’s universals, discussed below, eventually would morph into modern derivates such as class, race or gender, all of which share the dangers of abstracting from meaningful context. It is no coincidence that they became essential for totalitarians like Nazis, Marxists, or modern gender ideologies. As mass typologies they all gravitate—just like Pauline Chrisianity—toward the organic-visible paradigm of Aristotelian metaphysics, churning out surrogate truth claims which imitate divine incarnation. Like universal Christ who descended from On High, these typologies formed the metaphysical “clutter” of modern totalitarianism. Equally imposed from above and descending upon us and hostile to human nature they would eventually provoke the countercoup of naturalism and environmentalism.

By contrast, Judaism is gradually ascending and famously transcends human nature in an upward move toward the divine. By contrast, the Gospel—due to its metaphysical Greek credentials—descends onto human nature—the result of which is often hybrids of “passion and pathos” or, what was considered by Maimonides, the greatest Jewish mind of the Middle Ages, to be just dependable “clutter”, a clutter in the service of martyrdom and self-pity. This Greek disease was rarely taken up by Islam or Judaism, leaving them firmly wedded to transcendent trains of thought. Nevertheless, Jewish Kabbalah and Kalam philosophy became also contaminated with Hellenic metaphysics. St Paul’s quest for unity via universal equality is tied to immanence and victimology—something altogether different from active Jewish unity in transcendence, which creates resilience and self-sufficiency. From its first days, universal Christianity was therefore burdened with the curse of unresolved conflicts, conflicts mired in Greek metaphysics that took their latest form since the fin-de-siecle decadence as the sexual revolution that is with us still. Pauline unity was eventually to disintegrate as “incarnated” sexual diversity, as it were, splitting Christ into sparks of multiple organic identities. This clearly answers to the longing for a return to particulars and the centripetal sense of belonging, if narrowed into the biological categories of race and gender. Particularism was originally stolen by St Paul in his famous “neither Greek nor Jew, neither rich nor poor, neither male nor female” (Galatians 3:28)—a kind of metaphysical surgery that continues to haunt Christianity.

In other words, Paul abandoned the particular Jewish law and, with it, the timely spread of people’s biographies along the lines of piety whilst “walking before God.” He set off global universalism with his Greek or “spatial turn,” agglomerating multiple tribes attached to their land and languages. Yet this spatial diversity is centrifugal, necessarily turning its back on the family, and he had to compensate this by inclusion of all individuals indiscriminately regardless of their merits. The price for this was a Greek split between reality and afterlife or “two ages”. The “two ages” gave us the apocalypse and Christian afterlife, representing yet another break with Judaism. Frankly speaking: the postponement of punishment toward last judgement inverts the immediate postponement of pleasure in Judaism and takes away the foundations of transcendence.

It was Benedict Spinoza who resolved the problem of split reality and Christian ambivalence[2] by reversing the sanctifying upward “All in One” into the downward and pantheist “One in All”. The unresolved contradictions incorporated in Christ would later be disentangled by Martin Heidegger and inspired his discovery of the seminal “ontological difference”, i.e. the difference between the inward perspective of Adam II and the outward perspective of Adam I. The former is to be conceived as tied to transcendence and the internal-audible paradigm, also known as the system of slow thinking, while the latter is tied to the external-visible paradigm with its delusionary metaphysics, craving for virtual tangibles as proofs of divine rewards. As an example for this, Spinoza invented his centrifugal vehicle of animal instincts called “conatus”, the ever expanding ego rejecting the family. Reflecting his Greek credentials, Spinoza ended up with a split mind, oscillating between Jewish particularism and Christian universalism. It is the issue of form which brings us back to the tensions between Athens and Jerusalem. The modern predicament, image-laden as it is, can surely be read as a victory of Athens over Jerusalem. For these are the two leading, sometimes antagonistic cultural streams of the Western spiritual heritage. While Jerusalem is typically wedded to the word, Athens is fully absorbed by images. Jewish forms of knowledge are led by inner conscience and tend to be therefore autonomous or self-directed yet under the inner heteronomy of transcendent revelation, the “yoke of heaven”. By contrast, Hellenic knowledge tends to be other-directed or externally heteronomous.

In order to understand this difference, I will brush historical sources against the grain in order to expose the Western, Hellenistic bias, born from one-sided attachment to Athens. For image and gaze often militate against language and oral tradition. While the proud Greeks often protested against their dependency on the gods, leaving them in hopeless disunity, the humble Jews understood that embracing divine authority afforded them lasting unity and peace. The blessing of transcendence intelligence is the diminishing of vanity and pride of authorship, which minimizes rivalry. It is quite literally better to depend on a transcendent being than on multiple hybrids as the Greeks did, subject to the conflicting demands of polytheism. A recent example of persistent Western Hellenism is the awarding of Pulitzer Prize to Stephen Greenblatt. He received the coveted trophy in 2012 for his historical yet fictionalized account on Lucretius, the Roman disciple of the legendary hedonist Epicurus. According to Greenblatt’s plot, Lucretius’ manuscript De Natura had been rediscovered in a remote Bavarian Abbey during the Renaissance and became very influential thereafter. Greenblatt is known as an authority in Anglo-American letters after the death of Mike Abrams in April 2015, with whom he put together the signatory Norton Anthology of English Literature. Greenblatt, to my knowledge, is presently presiding over the American Canon.

Here is an example of the practical consequences of transcendent versus metaphysical reasoning: compared to the open-minded Norton Canon, the competing “Heath Anthology” is caught up in trendy terms of groupthink. Contaminated by political correctness, it appears at the same time more iconoclastic, making room for a wealth of particulars appealing to post-modern minorities at the cost of the classics. The fight against racism, for instance, should start with criticism of the slave-holding elite of Athens in antiquity, yet this issue is rarely touched upon by liberal academia. Yet it was the reception of Greek philosophy in the Renaissance and beyond which is marked by racial bias since it threw the fate of slavery in Athens under the carpet. This has been mainly the work of Western Cultural Protestants who have lost access to transcendent long ago. It is well known that Protestants associated themselves with Athens and Catholics with Rome. This explains why the slaves were simply forgotten when the first American constitution was drafted in 1787, still reflecting the continuity of slave ownership that ended only with the Civil War.

Mugged by Reality

If some chutzpah is in order here, we might think after all that God had started in Eden as an idealist and inevitably was to be mugged by human reality. Thus, a sobering gap had opened up between physics and metaphysics in the shame culture of Eden’s low hanging fruits. It would in the end leave Adam and Eve short-changed with expulsion and lifelong toil. This was then followed by the covenant with Noah suited by yet another with Abraham later. But the broader heaven of transcendence would only be made accessible to the proverbial stiff-necked Israelites at Sinai. Raised by a generation of former slaves and still lacking a Jewish persona, the children of the exiles from Egypt were eventually deemed capable of absorbing a comprehensive revelation translated by Moses. Nevertheless, the Torah even had to be revealed twice at Sinai to afford the Jews an important divine lesson: God started with the “visible” or written law first, inducing his people to trust their eyes more than their ears—as if the calamity of Eden had not been enough.

Yet from the history of mankind we gather that writ preceded the spoken word, making it the higher accomplishment offering access to transcendence. For this, we point to the famous example of the Phoenician cuneiform, a writing system for the banter of merchants, dating well before spoken language became the preferred way of human relations. Making an indirect reference to this, the Bible narrates that the written tablets were not good enough and had to be crushed by Moses upon witnessing the abominations of the Golden Calf. This comes as another biblical warning that visible perception easily slips into lower human appetites such as touch and greed. Hence Moses had to ascend again and the first thing he had to do there was to talk God out of his attempt to punish or even annihilate his own people. After that he listened carefully for the second time to God’s revelation, learning it by heart this time around. Only thus it could become a treasure, never to be taken away from him. This represents an ascending order of cooperation and burden sharing.

That God choose Sinai for his comprehensive revelation seems to be no coincidence. Far more likely is that God had thought about ways of mollifying command and authority through dis-embeddedness as a precondition for learning from experience. If Eden is described as a tempting heaven on earth, inducing immediate human failure, the desert was exactly the opposite with no temptation far and wide, instinct-wise a safe place for ambivalent human nature. The desert, however, is the place of utter dependence on our maker and hence it is conducive to all sorts of miracles, wizards, and creation out of thin air. In my reading, the desert being utter void with very little to see, almost like a “tabula rasa”, quite naturally became the place where God made yet another “start from scratch”. By looking at failed humanity, he would be again emulating creation “out of nothing” but this time giving a much more detailed account of revelation in the laws of the Torah.

Surely, this was a tough job after so many disappointments: first with the human couple in paradise, purged from the first transgression but nevertheless ending in debauchery and chaos, which in turn prompted the flood and a new start with Noah. In exchange for agreeing on the Noahide code, available to gentiles and Jews alike, God made a concession to human animal instincts by allowing the consumption of meat. This indulgence was introduced subject to kosher rules on preparing animals and ethical conduct which began with Noah’s seventh command: never tear out a limb from a living animal. It was only after the first excesses of debauchery that God felt obliged to take the animals out of the picture of his likeness and turned them into human prey in order to draw a more definite line between the fourth ontological level of humanity and the third level of animals. Vegetarians are adamant to reverse this step, pretending to know better and feeling entitled to trump Christian morality. But far from it, since we learned from Adolf Hitler that veganism is ideologically tied with same-sex attraction and an unapologetic embrace of our animal nature (Hitler initiated rigorous animal protection laws, adored his German shepherds, adhered to veganism, and was a practicing homosexual, according to Lothar Machtan, in his book, The Hidden Hitler).

Almost forgotten is the lesson about God’s carnal concessions after the flood, as it is told in the story of Cain and Abel. Their father, asking both for a meal, rejected the vegetarian dish of his farmer son Cain, despite being his firstborn and instead chose the meat dish of the hunter, his younger son Abel. Nevertheless, the following arrangements with Abraham, discussed in the first chapter—just like the covenant with Noah—are a case of divine burden-sharing, equivalent to a gradual shift of the Israelites from shame to guilt culture. Concerning the sinful cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, Abraham extracted one concession after another in his attempt to dispel God’s resolve to annihilate the human race for good. Abraham traded with God about the number of decent people he could find in the decaying twin cities: from 100 righteous men, he got his Maker to settle for ten—through today the minimum quota for holding a synagogue service. In the end, God would surrender punishment for just one decent human being. Yet again, the covenant with Abraham, sealed by circumcision, lasted only as long as the period of the patriarchs. It consisted of polygamous transitory arrangements of a shame culture with all its serious drawbacks and made Jews rife for advancing further to guilt culture and for Moses.

With Abraham, God had introduced the concept of his chosen people responding to the horrible experience of Sodom, and at the same time allowing for two more, potentially competing branches of monotheism, namely Islam and Christianity. However, Ishmael, issuing from Abraham after he impregnated his maiden Hagar, often served in biblical times as scapegoat, a vehicle for projecting evil onto the other. It would be abandoned only after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem when the scapegoat would be replaced by internal self-sacrifice (personal will) within the synagogue services. But still that period ended in another spell of Israel’s debauchery punished by the Babylonian exile.

God’s prudence of using competing faiths as a testing ground for Jewish loyalty and a means to secure the eventual survival of his message remains disputed because it left the door wide open for apostasy toward monotheism “lite,” allowing for waves of conversions to Christianity, Buddhism, or Islam. This remains pertinent given that Christianity carries elements of the “Old Testament” shame culture. By contrast, in Orthodox Judaism after the purgatory at Sinai, orchestrated by Moses, features of shame culture have been almost completely eradicated. Of course the caveat of “almost” reminds us that in moral history, or biblical philosophy for that matter, nothing is certain and nothing lasts forever. This much for any talk about Christian or Islamic succession of Judaism.

Now for the evolution of Judaism we can look with some satisfaction toward the divine strategic use of geopolitics. This is as true for Abraham leaving his home town in decadent Mesopotamia together with his family—a crucial detail often overlooked—accompanying him to Harran in Syria. Before imposing compliance onto his peoples as a whole, God had tried out a new start with just one exile, Abraham. He would become the father of a smorgasbord of diverse people again raised family-wise under God’s guidance and control. But, alas, even this individual approach ended with disappointment regarding the survival of divine intangibles: the selling of Joseph by his brothers, as if a he were property. Forgotten was the lesson of God’s sole ownership of mankind which he had taught the Israelites early on in the Akedah, the non-sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham.

Or is this all God’s providence? Yes, very much so, it would appear. For by now we are able to apprehend that this particular transgression: treating a human being as property, is of course intended to presage the Jewish fate of slavery in Egypt. It has been worked through with all the pedagogical zeal our maker could muster and recalls the big lesson about the flawed shame culture. For God, shame culture had become truly dysfunctional and exhausting since it meant for him to mete out punishment around the clock for any single transgression, just as in the Islamic theology, known as Kalam, which had prevailed with the school of mutakallimun till the end of the first millennium C.E.

Burden Sharing

Clearly this situation called for divine relief. Burden sharing is a principled and much older alternative to any passive Christian notion of afterlife or “two ages,” for it is a hands-on approach to piety wedded to personal commitment and promise made true. Divinely inspired action became such a blessing for the Jews because they knew the bitter taste of forced work under tyranny. And we can realize with empathy that, before the Israelites were slaves, God himself made that experience himself, by somehow becoming a slave of the passions of his people. This could not go on forever and it was from this unprecedented low point of Israel, stuck in slavery which had been dragging on for 400 years, that God, all forgiving ruler that he is, made yet another new start. This explains why he choose the desert which is best suitable for inculcating his message into “unformatted” slaves. To accomplish this, he had to be in full control of the environment.

In other words, playing safe this time, He wanted to raise a fully embedded people, their whole context included, in order to limit the risk of yet another failure to a minimum; no hidden tricks and no excuses allowed this time around. This tabula rasa was best suited to implement the full version of guilt culture, the only way to make every single Israelite personally accountable and thus get out of it a divine relief in earthly oversight. For this purpose of taking full human responsibility, the auditive paradigm of transcendence, covering the full panoramic ambience, would be superior to the visual paradigm which misses our embarrassing backside. Kant famously observed that the “ear draws us inside” which makes it the agency of internalization with the addition of language as empowering our conscience. By contrast, Kant ascribed to the visual paradigm the pull of distraction, driving us away from ourselves to the outside world. This makes the eye the vehicle of our appetites, externalization which also stimulates our fantasies. The separation of inner and outer self, later to be known as the ontological difference, is the premise for autonomy and responsible human agency.

Given these advanced mosaic arrangements, with everyone capable of looking after himself, God could expect a considerable relief to his own sanctioned business. Mount Sinai was a fitting symbol for God’s exalted position, watching over his people, and an amplifier for inducing respect and fear of the Almighty. Nothing else can elicit the Mysterium Tremendum and Fascinans better than a decent earthquake. If the mountain shattered, the Israelites would tremble too, regardless of whether they liked it or not. Hillel Halkin gives us brilliant examples of biblical imagery: “Onkelos, anxious as always to avoid idolatry, translates ‘God came down on it’ (Sinai) as ‘was revealed on it.’ Rashi, the medieval French commentator, having no such compunctions, tells us that God spread the sky over the mountain “as though covering a bed with a sheet and lowered His throne onto it”.[3] This is an example of authentic biblical language and its sensibilities to contexts, nicely maintained in the metaphorical term embedding. In Hebrew, we could find a great many of such examples but also in languages not affected by the Reformation, such as Russian. In both, the transcendental associations and meaning still dominate the way of reasoning and its expressions. The Reformation being an assault of Greek metaphysics on monotheism resulted in the domination of an alienated metaphysical layer of meaning taking precedence in the expressions. The biblical use of transcendental images does not allow for split or double meanings as common in metapyhsics. Rather biblical words are embedded in particularism or multiple associations, as opposed to binary dialectical meanings in Hellenism. We cannot elaborate on this here any further however.

Suffice it to state that, yes, Judaism is pretty much about a people being not only transcendentally embedded but equally immanently with Galilee, Judea and Samaria, or what the Romans called Palestine. This maintains a genuine psycho-physical harmony that always surprises or fascinates the sympathetic onlooker, because it obviously could not be copied in 4000 years by anyone. We will return to this kind of an almost naturalist metaphysics in some corners of Judaism’s heritage. Before written Hebrew Scripture surfaced after the Babylonian exile, the prophets had almost always emerged from the desert. Which means: fully embedded Judaism was only authentic in the oral tradition, consolidated at Sinai which had subsequently to be learned by heart in childhood. For in Judaism, the human mind is a living container for knowledge which is regarded superior to the textual representation. Proof of this is the essential vertical instruction, a direct transfer of divine revelation from biological parents to their offspring. This has been instituted by God on several occasions, expressively putting Abraham personally in charge, sealed off by circumcision. Only this way of transmission assured that preserving the unique desert-borne impression of intangibles ruling over tangibles which is still palpable in Biblical Hebrew. However, the written Torah would somehow contain a condensed Hebrew, less rich in associations than the spoken word of the Mishnah, written down much later. This explains why the Hebrews have always insisted on keeping both traditions alive, the spoken and the written revelation. The spoken Torah is certainly richer and closer to the divine voice.

Which brings us back to divine burden sharing depending on authentic transmission of Jewish epistemology. The Israelites were constantly memorizing divine oral revelation from Sinai. Finally, there are two amazing examples of God sharing his burden with man, a God assumed to reside outside of nature in eternity and infinity: First, the naturalist manifestation of imitatio dei with the trembling earth corresponding with human trembling in fear of God; second, hiding by covering: just as Adam and Eve cover their nakedness, the naked desert and mount Sinai are covered by God with the sky and clouds; this means the transgressions of the patriarchs, perpetrated in plain view as in shame culture, had to be covered up by God in order to make a new start with burden sharing in a guilt culture. To be sure, this was spoiled by the Golden Calf atrocity, for which the Jews are ordained to make good with their daily readings of Scripture for all times. The desert again serves as metaphor of the clean table. This is visible not least from the fact that the new revealed law of Sinai begins with the rights of slaves, of all people. Yet this celestial bedding over Sinai was noble compared to the previous sweeping divine vengeance of sin by the Flood. God kept his promise never to repeat the devastating flood, rising to the opportunity of the Golden Calf with a sophisticated response, the result of Moses’ negotiating skills.

With all this in mind the origin of monotheism may well be said to lie in the desert-born experience of sensual deprivation, the Israelites facing void, awe-inspiring silence and a harsh environment. Nothing can conjure up the desire for protection as the desert can; the feeling of visual void and displacement that was evoked at Mount Horeb comes through natural emptying out of the rigid visual faculty that tends to direct our attention to the sublime auditive faculty, amplified by language and responsiveness.

John James Audubon: Bald Eagle

In the desert, the sensual attachment of man to his environment seems uprooted or at least less palpable. This is understood as engendering the urge for artificial things to hold on, in particular intangible ones. One obvious demonstration of this is the invariable generation of optical delusions, fake realities known as Fata Morgana. Here, the visual imagination takes control over our mind and it gives us perhaps the closest experience to what we might call a feeling of metaphysics. It is quite different from the experience upon closing our eyes which triggers the longing for transcendence. Only birds naturally encounter a similar experience of void or very remote limits when rising up in the sky. There seems a naturalist case to be made for the experience of avian as analogous to human dis-embeddedness. Sensual deprivation, which might in both cases have been addressed by divine evolution, so to speak, provided a sort of natural metaphysical hold through pairing in monogamy, which is shared with humans by birds only. Let’s hear a voice of the famous Audubon society, the specialist on American birds, on the monogamous conduct of eagles:

“Bald eagles stay hitched until death do they part, often returning year after year to the same nest. While there, the pair continuously adds to the structure, so that after many seasons it assumes gargantuan proportions and stands as a symbol of their fidelity. In Vermilion, Ohio, one behemoth, used for more than three decades, measured 9 feet across and nearly twelve feet high, and was estimated to weigh more than two tons. Though the birds’ courtship rituals are spectacular in their display of aerial acrobatics, it is nest building that cements the bond between male and female. Dad’s contribution to his progeny doesn’t end at conception: He sticks around to help incubate the eggs and feed the offspring. Bald eagles, which are capable of breeding at about 4 years and have been known to live to 28 in the wild, are not unique in their sexual liaisons. According to Frank Gill, Audubon’s senior vice president of science, more than 95 percent of bird species is monogamous, making them among the most loyal members of the animal kingdom.”[4]

Now, as for humans, deprived from their natural context, fantasy fills in the void and creates its own world. Hence, in this situation the natural hold for the human soul is offered by the spoken word of the Bible. For Europeans the night may, if to a lesser degree, represent an equivalent to the desert experience evoking feelings of forlornness and void. This might be the hidden meaning of the expression “evening land”: the night as the universal format of void and a stand-in for the desert, enabling the reception of monotheism abroad. Fitting into this picture is the fact, albeit not very well known in the West, that in the Orient the new day begins with dusk not dawn, by which the usual perception of a reversed order is being validated. From there seems to originate the prejudice of the lazy Levant after the eponymous southern part of the Mediterranean Sea. Again what is overlooked here is that the night is more comfortable for work in the hot Orient. Another rarely acknowledged consequence of this is that hearing and voice dominate the dark hours in the Orient which suggests an almost default setting of the image ban. It certainly has favoured the image ban to remain effective all over the Near East. However, the Greek discovery of the third visual dimension over Egyptian two-dimensional reliefs also played out in these matters. Europe’s vulnerability, or its fatal attraction to the obsessive Greek image world would eventually spoil Western Christianity, but not Eastern Orthodoxy.[5] This is a likely culprit for the Western collapse of marriage, religion and family resulting in Europe’s nemesis: demographic winter and the dismal answer to it which is unregulated immigration.[6]

[1] Soren Kierkegaard: “The Concept of Anxiety“, 1844.

[2] Claude Tresmontant: “Hebrew Thought“ p.?

[3] Hillel Halkin: “Law in the Desert”, in: Jewish Review of Books, Spring 2011.

[4]John James Audubon: “Die Vögel Amerikas”, Benedikt Taschen Verlag, Köln 1993; for the quote see: https://www.audubon.org/news/do-eagles-remain-faithful-one-mate-their-entire-lives).

[5]Hans Ehrenberg: “Östliches Christentum – Dokumente“, Band 1: Politik, 1921, Beck München.

[6]David P. Goldman: “It’s not the End of the World – It’s just the End of You”, RVP Publishers: New York: 2011.

___________________________________

Dr. Friedrich Hansen is a physician and writer. He has researched Islamic Enlightenment in Jerusalem and has networked on behalf of the Maimonides Prize. Previous journalistic and academic historical work in Germany, Britain and Australia. He is currently working in Germany and Australia.

Read more by Friedrich Hansen here.

Please help support New English Review here.