by Justin Wong (March 2021)

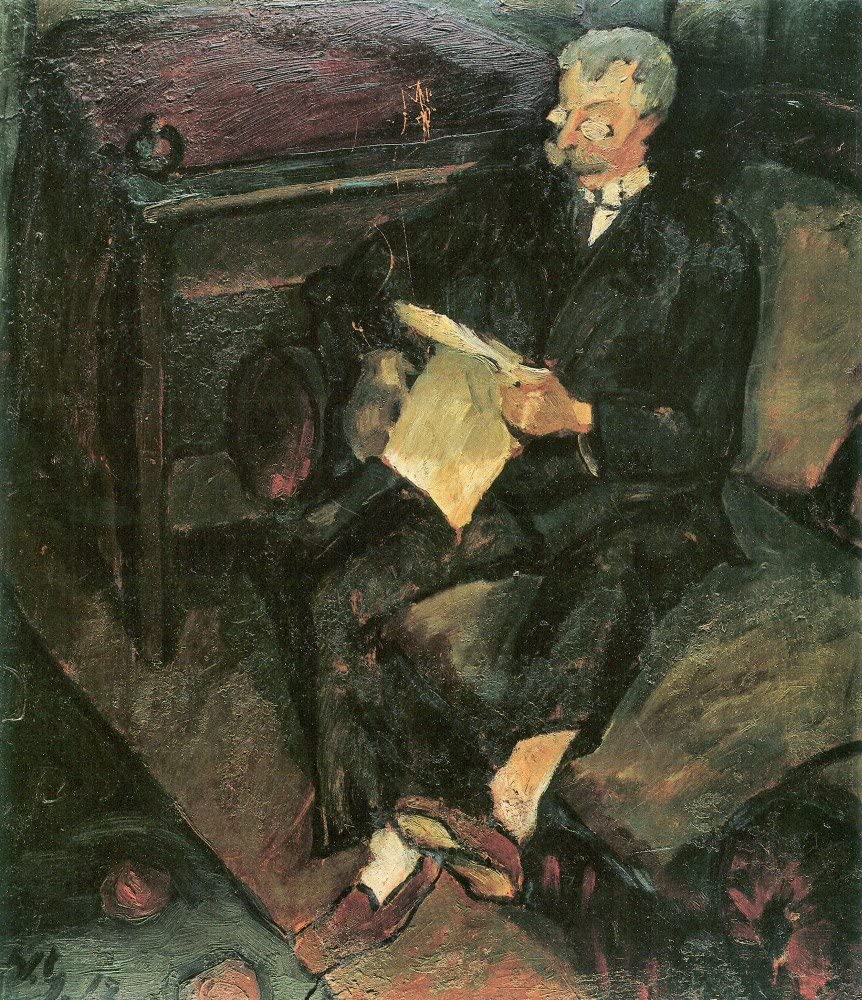

Father Reading, Walter Gramatté, 1917

When my wife was pregnant for the first time, when she was carrying what was to be our only son, she was in a thrilled state, the feeling of welcome hysteria could be perceived from her. I myself couldn’t exactly say that I was unexcited over the prospect of our being a family, that we would have connections that weren’t simply limited to her and me. That our house, which often felt devoid of other presence, was to overflow. Though I can’t say that I was wholly thrilled at such a possibility, the fact that I was to be a father, with responsibility, that I was to care and provide for other people, being the load bearing wall of their lives, frightened me. It wasn’t so much that I wasn’t prepared for the new role, ever since I heard the news of her conception, I was happy and thrilled to hear of these glad-tidings, as was she. I had stable employment, we were well on our way to paying off the mortgage, where its existence was soon to be a non-entity, something that would soon cease to keep me awake at nights. I certainly had my reasons for thinking this, and I felt although the time of us courting was fine, things between us had grown stale, where a change was needed. It was evident that we weren’t as close as we once were: when we were engaged; or in the aftermath of our ceremony, when sex and leisure was new for us to explore.

***

Though what frightened me to greater ends than this wasn’t being a father, it was being my father. For nothing scared me so much as turning into him. I had my reasons in this being so, in that he was overbearing, dictatorial, a bully, someone who from the point of view I had growing up, seemed as if all too intent on making my youthful existence one of torment. He seemed adamant on making my innocent eyes see through his lens of experience, to replicate the world-weary state of mind he had into mine. I made a pact early on, in the days of my nascent manhood, that if I was ever to have children, I would go about it in a different way. That I would not command as he commanded.

On the surface of things, my family, when I was growing up in greater London, had something of an idyllic existence, I came from hard-working parents who scrimped and saved, were prudent in regards to wealth. They managed to make their way in the solid middle-class, where the veneer of the lives we went about had a remarkable sheen. Growing up I had never known privation, none of my friends had, where I lived an existence free from want. So, the tales my mother told me of the hardships she endured, the non-existent meals she came home to, growing up in post-war Britain seemed untrue. As if they were tales spun to humble my sister and I in the entitled way we went about life.

In our house, the garden we had was immaculately kept, a lawn that was shaved and scissored on a weekly basis when spring and summer had gloriously arrived. In the beds, grew roses, grew hydrangeas, and a flourish of multi-coloured pansies could be seen in baskets which hung, rocking in the wind as a boat in an ocean from our porch arches. In the driveway there were always two cars, my mother and father each had their own means of transportation, and the interior was always well-kempt and weekly cleaned. The dog we had growing up lived in the conservatory, or on particularly humid nights as sometimes we enjoyed, she would find herself outside, asleep in what was the cool of the evening. Free and liberated from the trapped and oven-like heat of the house. This was worrisome, and although we lived in suburbia, in a built up and semi-industrial area, at the back of us, trains went by. Every once in a while, you could audibly perceive the thunderous roar of approaching carriages of the underground in fifteen-minute intervals being pulled along in both directions, from early morning to late evening. In winter, this carried on far past the period when the sky had donned its cloak of black, and you could see the luster from a moving train providing a scurrying lamplight, past the confines of our backyard, like a steel firefly, providing a welcoming though unsubtle illumination. Around this line of railway was a wooded area, where apple trees and oaks wildly came into existence, this was where the foxes were said to reside. Every once in a while, when no one was around hanging up clothes, or when none of us were at play, you could spot one walking by as if to stretch its limbs in the morning or afternoon hour. Our neighbours were an elderly couple of European immigrants, who came to England some several decades before my birth, fleeing from the Nazis as children. They had a daughter who returned home to stay with them every once in a while, who left bowls of food for the foxes that lived in the wilderness behind. We were frightened that our dog if left outside may court danger, that a fox biting her might transform her jovial and sober mind into one of cruelty and ill-intent. Which was why Mother was often hesitant in leaving her alone in the jet of night, regardless of the heat that was obviously unbearable, making her pant as would one in a fever dream. Such things fortunately never happened.

My family also had much in the way of material possessions; we were at the forefront of every fad. I was the first to have a Personal Computer amongst all my schoolmates, I remember my father bringing it back one evening, telling me passionately of all the things it could do, the games I could play, the encyclopedias, the internet. From then on, my friends found their way to mine when school had finished, when we wished to do anything that didn’t involve being outside, in the dreary rain or snow, cycling our bicycles through slush and slippery grounds.

This materialism was offset with a religious fervour, as the squares of black and white are offset on a chess board. Where my mother, my sister and I, made our way to the church on Sunday mornings, dressed in what was our finest clothes. These were uncomfortable to wear, and such that I didn’t put on in my free time, dress that seemed above all most unsuitable when playing out and about in the garden, or kicking a ball with my friends, in one of the parks that wasn’t a tremendous distance from where we lived. Seeing as these places which served our recreational needs were scattered about the city, there was always somewhere to play in the not too far distance. My father never went along with us, his beliefs evidently didn’t mirror my own. The ones in which I was brought up to inhale and live my life by, the Christianity which provided me with a stable and unwavering ground in which to live, in which to understand my place in the cosmos, within the ineffable mystery of life. I remember being a believer from early on, and loved church, Sunday School, the stories we were told, the wisdom from the book. In the building I found myself in on Sundays, I would stare up amazed. In awe, shaken to the core of my bones, where I could most evidently feel a spiritual presence, the grace of God shower down upon me, becoming alighted as a consequence. What to me, seemed like an ancient building, was a place that was regular in my formative and juvenile years as was my grandma’s house, a place that was to me most familiar. The masonry of its pewter grey stone, the rattling and wheezing chestnut-coloured pews, the cherry red King James Versions that sat therein. The pulpit was elevated above us, where the Reverend taught me of the fear of God, and consequently his love, in his vestments covering him, from neck to foot, someone who seemed as if brought back from a period when eminent men draped themselves in eccentric garb, to distinguish themselves from those of commoner breed, the normal among us. Though such a place was wonderful for me to attend, enriching my existence as music does the country scenery.

Though my father didn’t share this wonder with me, or the others of my Family’s remaining members, he didn’t believe as I was taught to believe. As a result, as a dire consequence of this, there was a division in my household, where two competing worldviews seemed to be at war, the pious and the profane. I oft wondered if he was more of the former and less of the latter then my life would cease to be as tumultuous as it was when I was growing up, that spiritual guidance and understanding may have made him milder, less prone to the self-defeating and violent streaks that he was known to possess, and that above all were directed towards me. It wasn’t just that out of nowhere and unannounced he assaulted me, inventing some excuse as to how I did something wrong, of how I transgressed some unwritten law, which beating me would fix. Perhaps greater than this, was the way in which he always seemed to be critical, putting me down in slight though penetrating ways, where I always managed to be doing something wrong, regardless of how petty and innocuous this was. He was as a spectre that haunted the house, that continued on in my mind into the distance of my manhood. Where his influence, regardless of how far I had travelled away from him, seemed never to wane. His presence always known, like the hallucinations of schizophrenics, who always in their waking life see phantoms that aren’t, who are privy to things no one else is knowing.

This endless onslaught of criticism, this facet of senseless discontent seemed to spoil what was otherwise, for me, an idyllic boyhood. Although I can’t say that my life was free from troubles, there existed bullying, ostracism, and other such things, at school, and by some of the neighbourhood thugs, the deadbeats that hung around. People who were all too eager to pick on those of lesser strength, to assert their fragile sense of manhood. Though in general, the good eclipsed the bad.

Such a reality I suffered growing up, made me doubt conventions, the prototypical bourgeoise way of life, the materialism. The fact that the worth of life should be measured by all things, prosperity, that made me visit Florida twice, the Canary Islands, the Bahamas, Spain, and France before the age of fifteen. For in my case, underneath such a life, festered an unspeakable dissatisfaction, an underlying unrest, an ennui. This was clear to see on my father’s end.

As knowing of God as I was, even I couldn’t myself say that I was wholly understanding of all the doctrines of the faith that I was raised in from young. Although, I most ardently lapped up whatever in the way of dogma that was given to me, such things as original sin, predestination, and free will confused me as did theoretical physics. Regardless of this, I felt as if through whatever beliefs I had, I earned salvation, that through faith I was saved. My wife, who attained a degree in Theology, who was more well-read upon these subjects, tried to convey to me her beliefs that above all seemed as if harsh. She was raised in a home that was contrasted to the one I was reared, and her father, as kind-hearted as he often to me appeared, at least when contrasted with my own Father, was Calvinistic to his core. He was someone who doubted man’s own capacity to save himself, that such things were worked upon by unseen forces, that such people were elected before the foundations of the world.

During the period of her pregnancy, when she was still at work nurturing our son, who we were to name Julian, in her womb, we talked little about such grave, serious concerns. The capacity of man’s will to provide himself salvation figured little in our lives, as did other such mysteries. We were excited, getting ready for our first child, where all our energies were spent on this task. In such circumstances much had to be bought, and I would often drive her to a supermarket or other outlet where we could buy the necessary things needed, so as to be prepared for this evident milestone in our lives. It was nice seeing her in this capacity, and although she wasn’t what anyone would call harsh to glare upon in her pre-natal days, she appeared now when pregnant, as glowing as an ember. Someone who never looked more-healthy, and at her greatest as if motherhood was the thing above all the others she was destined to do.

In the days of our dating, in the days before we were married, I spoke candidly to her of my past, the life I had before I reached maturity, a life of joy melded as one with horror. I tried to convey to her that I would like to go about being a father in a more jovial and supportive way. That I would except for extreme circumstances, spare the rod. That I would be less domineering a father as I knew my father to be. As my wife grew fat in growing our first child, these conversations came up again, the anxieties I spoke to her of previously, of me being a father, seeing as this was coming into fruition, became more evident, more pronounced.

“I don’t know why you worry so much. Believe me, you’ll make a great dad,” she said this, as if to shew away any and all of my anxieties.

“Well, I certainly hope that is true.”

“Look, my role in being a mother is more important than yours, I have to breastfeed him, clean up after him, and care for him 24 hours a day, you don’t see me stressing?”

“No, I suppose not,” I said to this, and perhaps she had a point, and there were obviously countless among us, that had children, and evident from the blasé way they went about in the rearing of their offspring, that the possibility of wounding their children, figured little in their litany of concerns. Perhaps my wife, in the roundabout way she went about suggesting this, was right, that I was perhaps being a tad overly cautious.

As the months of her carrying our child went by, trundling along like a sturdy carriage being pulled along by a horse, in the aftermath of her being impregnated, carrying my first born, and it wasn’t long until the six, seven and eight-month mark came upon us. Where her stomach, once so flat a thing that a ruler could rest upon it, began to inflate as a balloon before popping. The feeling of joy and anxiety haunted me. So that I felt ready for this moment to occur, her releasing my son into the world with whatever joys and miseries this contains with it, so as to get the wait out of the way.

On one day, on the cusp of it being nine months exactly, I received a phone call, she told me of her water breaking, pouring out of her and on the kitchen floor as a garden tap. She said that she was getting an ambulance there, and as I was at work, stranded some distance away, I told her that I would meet her there soon. It was a wonderful journey, and of course I prayed for my Wife, and the baby to be, that they would be safe and healthy. Also praying that I would be able to get there in one piece, despite the urgency with which I was travelling. It was a picturesque day of autumn, and half of the leaves, the things that were once so evidently in the months leading up to this, on the trees, had fallen to the ground, scattered on the lawns and pavements, like brown crisp confetti. The breezes that blew, scattering them about, had more than a bite to them, that made one dress in layers, and become reacquainted with the wardrobe that was discarded in the warm and fruitful summer. He was to be an autumn baby, and I myself as a child was born to this season, in the world cooling from the oppressive spectacle, the heat of the months before.

The pregnancy didn’t last as long as I expected it to, and after a while, when she was in the hospital bed, she managed to bear my son. The duo we entered there as, multiplied into a trio, and we went out with little Julian, the creature of six or so pounds in our arms, where our familial life was to commence from thereon, where new responsibilities were taken on.

***

The years which followed this momentous occasion was nothing short of idyllic, and my Wife took the role in a way in which I only knew she could, taking on the responsibilities as if it was second nature. Going about life in an instinctual way, as if a cat chasing a mouse. I myself knew nothing about this, this aspect of parenthood, and rather than upsetting the harmony of all this, her flourishing like a watered and sun-drenched garden into her role as a mother. I decided to do what I knew how, to retreat back into the cocoon of my work, spending hours, doing my best to be a stable provider. From this, the drive and focus I most evidently showed, I was promoted, into a managerial role, which was good news for my wife. The amount of work I was given, my newfound responsibility, made me work longer days then previously I was used to. It wasn’t so much that I was spending more hours in the office, though when I returned home, from the restless day, I still found myself opening my laptop, completing this or that aspect from a project I was at work on that needed to be done for the coming day.

“Don’t you think you’re working too hard?” my wife said to me one evening.

“Well, I have to, I have all this new stuff to do, besides you can hardly complain, you like all this new stuff we got?” I said, though I was aware that perhaps I could sound a tad bit contemptuous, as if the only thing she cared about was money.

“Yes, but sometimes, I would like to see you, you know, just to be together, so you can play with Julian, be a father to him.”

“Yes, I promise we’ll do something at the weekend.” I said to her, as I continued doing what I was doing, which was typing, filling out spreadsheets, something that urgently needed to be completed for the coming day, when I was to present some or other information to heads that were above me.

My life began to slip in inverse proportion to how successful I became, and in around three years since my son was born, I gained another promotion. The house once so humble a sight, expanded, becoming bigger, in us getting an extension to the back of us, a place that would work well as a games room, somewhere we could relax at the day’s end. Though in addition to this, the house was filled with things, a fifty-inch television in the living room, along with others in different rooms in the house, along with a home theatre. The company car I was given was a top of the range BMW, something that I never wanted to let go of, something I stared at as it sat in the drive, with its indelible silky sheen, that was like a black mirror that reflected a face as clear waters.

When I did manage to get some time off of work, when I was able for the summer to get a respite away from it all, we went away as a family, for long weekends, to a far off and beautiful spot in England or Wales. Or in summer we would make our way abroad, though the whole going abroad thing was more novel to my wife, being brought up in humbler, less worldly circumstances. She never before had flown on a plane, nor had she seen a country other than England, and relished the sight of somewhere other than home, a culture and a way of doing things other than she had known.

I worked myself till I had nothing else to give, and though we enjoyed days out, and trips abroad, my day-to-day duties as a husband and father began to deteriorate in the ensuing years. I tried my best to play with my son, to teach him all that needed to be learnt, most of the time we interacted with each other as he began walking and talking, I was busy in a different world, concerned with payrolls and taxes, production and reports. I humored him, tolerated his being around, and although I loved him as only a father could, he was above all things disruptive to me.

“Daddy, Daddy, look at me!” he would often say.

That’s great son,” I would often reply, whilst never looking up at him, my face fixed upon my work.

Though one day when I was working, when he began talking, I was oblivious to all this and I humoured him as I always did.

“Look at me, Dad,” he said.

“That’s amazing,” I said though in the corner of my eye, I could see something wrong, and one of the speakers that sat in the living room, began to topple over as he attempted to mount it. The whole thing tumbled down, and along with-it a nearby vase filled with flowers. I could see that he wasn’t so affected by this.

“You absolute idiot, I told you not mess around there, you’ve gone and destroyed my speaker along with Mum’s vase,” I said berating him in this way, before smacking him around the mouth.

My wife, who heard all of this cacophony from the kitchen, rushed in, and seeing me treat him like this, picked him up and said, “It’s alright, Daddy doesn’t mean it.”

In that moment I saw myself transform into the one thing I wished more than anything not to transform into, my father. It was as if the ghost of him lived and breathed inside me, where at work inside me were demons, acting on behalf of things seen in a previous life. I had potentially scarred my son in the way I myself was scarred, that the sins of my Father were passed on to me, which was an unsettling reality. It was perhaps in this moment, in the aftermath of my transgression, in the wounds I in turn gave to my son that something that perplexed me, became ever so clear.

The doctrine of original sin that eluded me ever since young, which said that we are all guilty for the sins of Adam, remained to me a mystery. I didn’t quite understand how I was responsible for something done thousands of years before me. It was clear that I was able to ingest the sin of my father from his influence and him being in my life, though previously I wasn’t so sure how this related to the here and now. It was clear to me now that my father’s sin lived in me as much as my grandfather’s sin lived in him. Then perhaps I too have become sinful living and breathing the air of the fallen world created for us by Adam. When my son grows into maturity, my sin would live in him also, only to be passed on to his son, my child’s child, where it too would exist, deep in the heart’s core of those yet to be born.

__________________________________

Justin Wong is originally from Wembley, though at the moment is based in the West Midlands. He has been passionate about the English language and Literature since a young age. Previously, he lived in China working as an English teacher. His novel Millie’s Dream is available here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link