The Treasure that is Literature: Re-Reading for Self-Discovery

My reading of George Eliot’s Middlemarch after 40 years and what I gained

by Richard Kuslan (July 2021)

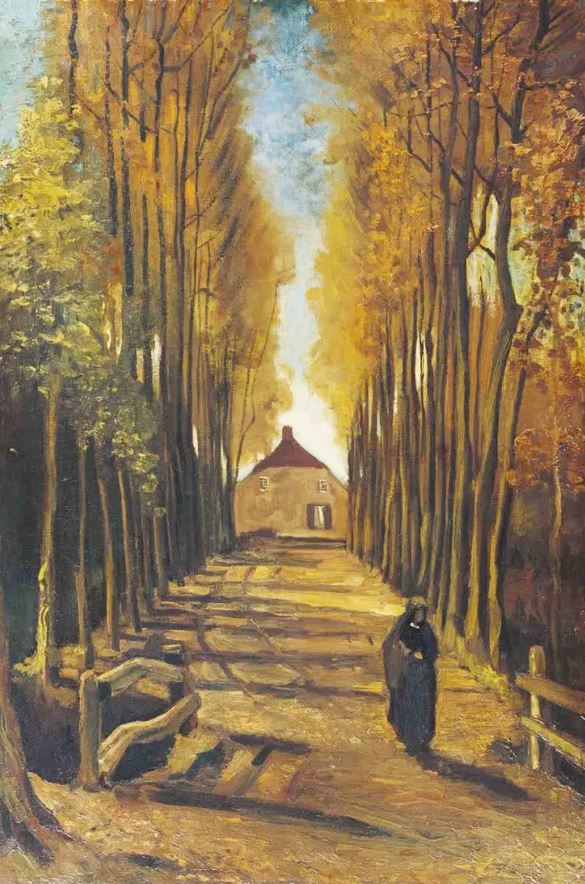

Avenue of Poplars in Autumn, Vincent Van Gogh, 1884

Can one be false to be true?

Literature is falsehood that persuasively conveys truthful essences of human life. Devoted readers discover meaning, via literature, by which they may live more nobly and wisely. It is axiomatic that an author plumbs human consciousness while disclosing the author’s own. I was unaware until my sixth decade that literature reveals the reader to himself.

Re-reading literature mines of self-knowledge. It is akin to watching one’s childhood home movies; doing so reveals what we forgot, what we have grown away from, what remains, and what new qualities have developed. The autobiographical knowledge I gleaned from re-reading demonstrates to me the life-long value of literature.

40 years after I first read George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871), I read it again. While searching for nutritious entertainment among the TV zombies, drug dealers, prison stories, and pornography our family stumbled upon the 1994, Louis Marks BBC adaptation of Middlemarch.

Surely, I thought, Juliet Aubrey enacted a steamier Dorothea Brooke than I remembered the character to be. In my recollection, Dodo was physically unprepossessing and unconscious of herself sexually, but possessing a passionate mind and an unsettled soul that yearned to understand Divine truths, obtained at the feet of intellectual giants. I could not reconcile the depiction of Miss Aubrey in the 1994 adaptation with the character I recalled from 40 years prior.

Then it hit me: Perhaps I no longer saw these characters in the same way because I had changed. That did it: I just had to re-read Middlemarch. As I re-read it, I discovered just how much I had changed.

Here are three of my self-discoveries, gleaned from a single re-reading of Middlemarch. 1) Characters whom I at 18 had admired and by whom I measured myself, I now pitied for their ignorance and foolhardiness. 2) Characters I had contemptuously dismissed as abject and unforgivable failures of will had become objects of wistful commiseration, deserving, instead, mercy and compassion. 3) I recognized the appropriation of divinity for ulterior motives, so as to camouflage evil under a mask of moral righteousness.

1) Dorothea and Idealism

As a young man, I read myself into the young idealist, Dorothea. She yearns to epitomize a fantasy of holy scholarship that discovers secrets of higher being, embodied, so she thinks, in Casaubon, who becomes her husband. “Here was a man who could understand the higher inward life, and with whom there could be some spiritual communion; nay, who could illuminate principle with the widest knowledge: a man whose learning almost amounted to a proof of whatever he believed!”

I saw myself in precisely the same way, intensely focused upon my esoteric studies no other student I knew had the least interest in (like Dorothea), and idolizing several scholar-instructors (who were not hacks like Casaubon). Unlike Dorothea, I had a bit more on the ball intellectually than Eliot gave her, but at age 18, I conjured her what I had, and in so mistakenly imagining her to be like me, I admired her fervently.

Dorothea, I find now upon re-reading, is a harmless creature, perhaps even well-intentioned, but blinded by an obsession with her own spiritual yearning. Yet, while she yearns, she never seems to act, settling instead into a comfortable discomfort, the state of passive recalcitrance. I recall wondering, years ago, why she had the nickname, Dodo. But now I understood: What a silly girl! I wondered, was the younger me congruent with the Dorothea I now saw?

Unbelievably, I had totally missed the gag factor: she threw over a handsome, vibrant, steady, reasonable, intelligent, caring, and wealthy young man, who had begged for her hand, for a withering, gray, dilettante 30 years her senior, who could not even give her a good roistering. Yikes! The idea is totally vomit-inducing to me now that I am Casaubon’s age, but at age 18, I thought nothing of it. Was her motivation all the while to avoid sex? Did she finally give in when Ladislaw’s sexual inevitability proved insurmountable to her? Neither of these questions would have ever occurred to me at age 18! Talk about innocence that is its own kind of ignorance.

2) Lydgate and Failure

Dr. Tertius Lydgate enters the novel promising great advances in medicine; he dies at 50 having failed to achieve anything of note, other than “leaving his wife and children provided for by a heavy insurance on his life.”

At 18, I had only the most abject spite for him. I remember asking, incredulously, how was it possible for a talented man of high ideals to fail? Lydgate must have been the cause of his failure, for it was certain to me then that the world was just, that talent was always rewarded, that ideals were achievable, that greatness was in the palm of one’s hand for the taking and that failure was the product of a weakness of will: a flaw in the person. To the 18-year-old me, the man who was not John Galt was Biff Loman.

20 years after I first read Middlemarch (and 20 years before today), I had achieved, if not none, but then very few of the “high-minded goals” I had set out seemingly so resolutely to achieve. As mirthfully as one might put it, I had become the “sadder, but wiser girl” Meredith Wilson had Robert Preston croon about. So it came as a shock and a powerful intoxicant to read, around the age of 40, George Orwell agree with my sentiment at the time that “A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying, since any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats.” (Orwell, All Art is Propaganda.) Surely the 18-year-old who would have disinherited the 38-year-old me, didn’t know this; and the 58-year-old would forgive them both their pitifully limited understanding.

Eliot did not give Lydgate the chance to renew and overcome. Where the writer fails her character is in the aspect of a male life that was unknown to her, and is, in fact, poorly known by men even now. Daniel Levinson, in The Seasons of a Man’s Life, a study of transitions in the lives of men, writes: “Those who betray the Dream (like Lydgate) in their twenties will have to deal later with the consequences. Those who build a life structure around the Dream in early adulthood have a better chance for personal fulfillment, though years of struggle may be required to maintain the commitment and work toward its realization (p.92).” However, even after the “mid-life transition,” which usually comes in the fourth decade of life, some men are able to turn things around and yet achieve a full life in later years which fulfills the “imagined drama in which he is the central character, a would-be hero engaged in a noble quest (p.246).”

Now, a decade older than Tertius at his fictional death, I have fulfilled many goals and ideals which, as a young man, I had set for myself and altogether in a wiser, more satisfying, intelligent and compassionate way. Poor Tertius never had the chance because Eliot did not give it to him. In another imagined world, he might have turned it around, as I did. But the 18-year-old me, so convinced of his omniscience, could, of course, never have known any of this; the 38-year-old would only barely consider it, yet think it impossible; the 58-year-old me would prove the both of them entirely erroneous.

3) Bulstrode and Moral Self-Righteousness

Nicholas Bulstrode is the village banker who once worked for a fence in London. He married the fence’s widow and, though he professed to help find the widow’s missing daughter, kept secret the daughter’s whereabouts, thus engineering his duplicitous inheritance of the estate intended for the girl. When Bulstrode’s colleague visits years later to blackmail him, the townsfolk see through the man who for decades had draped himself in piousness to hide his iniquity. The unmasking comes with a grand sense of divine justice that is as piteous as it is satisfying.

At 18, Bulstrode was to me just a disgusting old man. His thrilling public unveiling I had somehow found anti-climactic. I was totally unmoved by Bulstrode’s public ruin, or his recondite and cathartic penance before his suffering, innocent wife; I was indifferent to the reputational injury Lydgate suffered by association. Was I so insensitive to personal catastrophe? I must have been. Perhaps I thought it just desserts and left it at that.

The fear of being-found-out that one is not really what one would like others to believe is so strong as to compel the creation of an alternate reality in the mind that convinces oneself of one’s own righteousness and rectitude—despite one’s own self-loathing.

I caught none of this at 18. Now, I see deception and self-deception of a similar nature demonstrated every day, especially among the soi-disant woke; I pity Bulstrode’s honest, steadfast, long-suffering wife whose reputation has been inalterably stained owing to no fault of her own; indeed, I pity Bulstrode.

This is what I learned about myself from re-reading of Middlemarch. Quite an unanticipated harvest.

Joseph Bottum, in his Decline of the Novel, writes, “…for nearly three centuries, the West increasingly took the novel as the art form most central to its cultural self-awareness as the artistic device by which the culture attempted some of its most serious attempts at self-understanding. And the form of that device was developed to explain and solve particularly Protestant problems of the self in modern times (p.15).” It may be that “as the main strength of established Protestant Christendom began to fail in Europe and the United States in recent decades, so did the cultural importance of the novel.”

But readers—my hunch is there are many of us—can and do continue to enjoy the harvest of self-discovery that the novel engenders. My experience is that the importance of the novel to the culture of the individual, especially the American, has never been greater than right now. I predict that as more of us reject the culture of nihilism that would annihilate what is good and hopeful in us, the novel will turn a deaf ear to the siren song of anomie to once again answer its original call to instruct, to inspire, and to uplift.

_________________________

Richard Kuslan is an admirer of Donne, Sheridan, Byron, LeFanu, Trollope, Orwell, Sacheverell Sitwell, Christopher Logue and Jean Sprackland, among (many) others in the English language. He marvels at meaning’s fecundity when language is constrained by form and delights in the melodies that take to the air when the beautiful is read aloud.

Follow NER on Twitter