The Value of Wit

by Ben Sixsmith (October 2018)

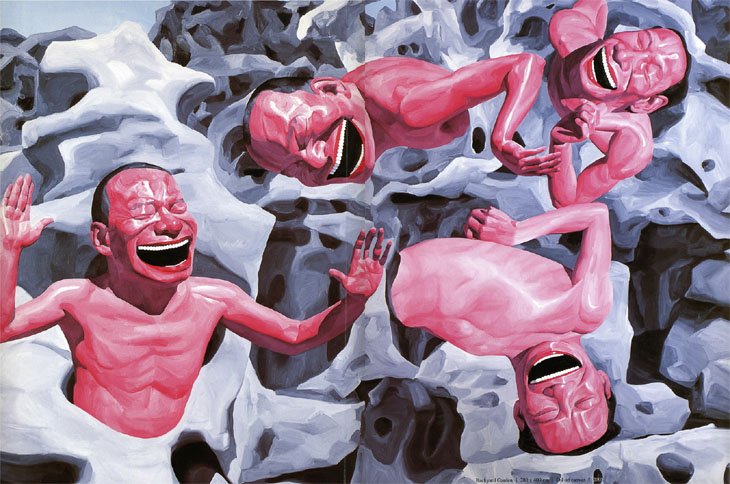

Backyard Garden, Yue Minjun, 2005

There are many things one might expect from a Catholic priest’s book-length defence of the Christian faith but fun? No, not fun. Apologetics, yes. Philosophy. Theology. A little history. Some social criticism. Perhaps some literary references. Fun? That is hard to believe. Yet Broadcast Minds, Ronald Knox’s 1932 response to early advocates of varieties of scientism, is a lot of fun.

A Spectator review from the period maintained, in fact, that Knox had had too much fun at the expense of his targets: “After a time we get rather tired of the excellent bowling and the steady fall of wickets, and wish that a member of the other team would make a few runs for a change.”

The reader of our time can be more appreciative. Knox—far more famous in his age than ours—takes on people we know as titans, including Huxley, Russell and Mencken. The experience of reading his little book is more akin to watching an obscure young boxer land blow after blow on men you had been told were all but unbeatable; a little repetitive, perhaps, but still an impressive exercise in giant-killing.

The fun aspects of this book are significant not just for the inherent pleasure of enjoying them, but as Christians and conservatives have something of a reputation for being humourless, stuffy and self-regarding. But Knox does not make one laugh merely for the sake of laughter. His elegant wit illuminates the fundamental absurdities in the work of the targets of his prose. Replying to H.L. Mencken’s cynical remarks concerning the existence of Christianity as some kind of profit-seeking scheme, Knox observes:

. . . whatever one may say of the sixteenth-century Church in England, or of the nineteenth-century Church in America, it is quite evident that our ceremonies come down to us from times when our priests, far from deriving either dignity or profit their calling, found in ordination only a short cut to the lions.

The humour—and there is humour—arises from the contrast between his casual prose and the shocking image, and the gulf between Mencken’s idea of fat, rich, comfortable priests and the luckless martyrs his allegations obscure. But the wit does not replace profundity; it is the platter on which it arrives. It provokes amusement for being artful and incisive; not for being quirky, or insulting, or absurd.

Christian apologists were fighting an uphill battle. It would be nice to suppose that one’s chances of being successful in debate rely on one’s ability to present empirical data or philosophical arguments in a rigorous and intelligent manner—or even one’s rhetorical passion and charm—but it has much to do with one’s material and ideological environment. The scientific revolution had encouraged people to think in the terms of materialism, and advances in mass media and birth control would soon enable a cultural trend towards moral liberalism. One need not even believe that Christianity is true—this author being a sympathetic agnostic—to believe the era was unfavourable to its defenders whatever the merits of their argumentation.

.jpg) Perhaps there were no merits, an atheist might respond. To know this, critics of theism would have had to have refuted its essential premises. Knox argues energetically that in this task they failed. Huxley, for example, reminds him of “the character in The Man who was Thursday who knew all about Christianity because he had read it up in Religion the Vampire and Priests of Prey.” Huxley criticised William Paley, then, whose argument from design has a peripheral place in Christian history, but somehow never touched on Thomas Aquinas. We know that new atheists have made the same the mistake, wedded as they are to scientistic argumentation. (Richard Dawkins did at least attempt to refute the Five Ways, but attacked summaries of them, not the arguments themselves.)

Perhaps there were no merits, an atheist might respond. To know this, critics of theism would have had to have refuted its essential premises. Knox argues energetically that in this task they failed. Huxley, for example, reminds him of “the character in The Man who was Thursday who knew all about Christianity because he had read it up in Religion the Vampire and Priests of Prey.” Huxley criticised William Paley, then, whose argument from design has a peripheral place in Christian history, but somehow never touched on Thomas Aquinas. We know that new atheists have made the same the mistake, wedded as they are to scientistic argumentation. (Richard Dawkins did at least attempt to refute the Five Ways, but attacked summaries of them, not the arguments themselves.)

Of course, we know the targets of Broadcast Minds enjoyed more success than its author but many a bold, skilful battalion has been overwhelmed by an invading army and yet inspired generations who followed them. Knox was aware of the need for inspiration. Writing in response to Bertrand Russell’s cliché-crammed The Conquest of Happiness he mused:

The trouble today is that disillusion is not confined to . . . any literary coterie. It is, I should say, particularly common among men and women who have outlived the first ardours of youth, and are reflective enough to think at all. Possibly they are wrong; possibly when they have tried Lord Russell’s treatment for unhappiness they will lament no longer. “That Russell feeling” will have changed the world for them. But in the meanwhile they must not be dismissed as poseurs, effete reincarnations of the Byronic spirit. They want a philosophy of life; and the question is whether the temperate eudemonism of Lord Russell will meet their demands.

Once again, note the lightness of touch. There is no pathetic straining for the reader’s approval. There is no wild posturing or idle abuse. This, I think, is how to attract intelligent readers while maintaining a sense of pleasure in one’s work: allowing for comedy in the keenness of one’s observations.

.jpg) To be sure, there is being funny and there is being frivolous. Much of the Christian faith, the conservative tradition and, indeed, earthly affairs at large demand a seriousness that respects their human and spiritual implications. Still, there is a difference between seriousness and humourlessness. The former offers one the chance to weave rich tapestries of tone. The latter paints the world in grey.

To be sure, there is being funny and there is being frivolous. Much of the Christian faith, the conservative tradition and, indeed, earthly affairs at large demand a seriousness that respects their human and spiritual implications. Still, there is a difference between seriousness and humourlessness. The former offers one the chance to weave rich tapestries of tone. The latter paints the world in grey.

Christians and conservatives, I think, have at times confused the two. Evelyn Waugh and Malcolm Muggeridge—among the funniest men of the Twentieth Century—became more priggish, pedantic and pompous when they discussed religion, leading to the famous, or infamous, debate where John Cleese and Michael Palin ran elegant circles around a blustering Muggeridge on the subject of their film The Life of Brian (a film which he evinced no sign of having seen). Knox enjoyed far less renown in the world of letters but his wry, witty approach was superior to theirs. One can lament and laugh at ignorance and ideology.

___________________________

Ben Sixsmith is an English writer living in Poland. He has written for Quillette, The Catholic Herald and The American Conservative, among others. His forthcoming book is Kings and Comedians: A Brief History of British-Polish Relations.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast